In my 20s, I longed for what Virginia Woolf in ‘A Sketch of the Past’ (1939) called ‘moments of being’ – those exceptional experiences that stand out in memory. There was the time I fell from a cornice, snow exploding as my body dropped through the air. The time a grizzly bear chased me down a mountain, jaw opened wide as she roared in my face. The time a pack of eight wolves surrounded me and my husband as we walked across the tundra, the lucid gaze of one fixed in my direction as he trotted just a few yards away. In each experience, time expanded and each little instance became dense with memory. I was utterly awake and aware, wondering what might happen next.

In the same autobiographical essay, Woolf also discusses moments of non-being. She writes:

I have already forgotten what Leonard and I talked about at lunch; and at tea; although it was a good day the goodness was embedded in a kind of nondescript cotton wool. This is always so. A great part of every day is not lived consciously. One walks, eats, sees things, deals with what has to be done; the broken vacuum cleaner; ordering dinner; writing orders to Mabel; washing; cooking dinner; book binding.

Moments of non-being lack the crisp details of more indelible experiences and often coincide with activities we repeat in our everyday lives, which makes it hard to remember their granular details. Rita Felski, professor of English at the University of Virginia, describes this distracted perception of daily life in her introduction to New Literary History Vol 33 (2002): ‘We act without being fully cognizant of what we are doing, moving through the world with the uncanny assurance of sleep-walkers or automatons.’

I’m in my 30s now, and my days often pass in a smear of non-being, marked by the rhythms of daily life. Take today: I nursed the baby, changed her diaper, made oatmeal, went for a short walk, trying to lull the baby into a nap, then gave up and carried her home on my hip. I watered the plants in the greenhouse, water bottle in one hand, baby in the other as she grabbed the leaves of squash and cucumber plants. I heated up a sweet potato and red lentil soup, which I ate from a mug. I nursed once more, thinking she might nap now, and when she didn’t, I tried to hand the baby off to her father so I could write. I was quickly recruited back when she cried. I folded laundry, fried two eggs, ate several disks of chocolate, refreshed my email. By tomorrow, or tonight, most of these details will be gone, the specifics of today’s nursing and laundry-folding and oatmeal-making melding into all the other times I’ve done the same thing.

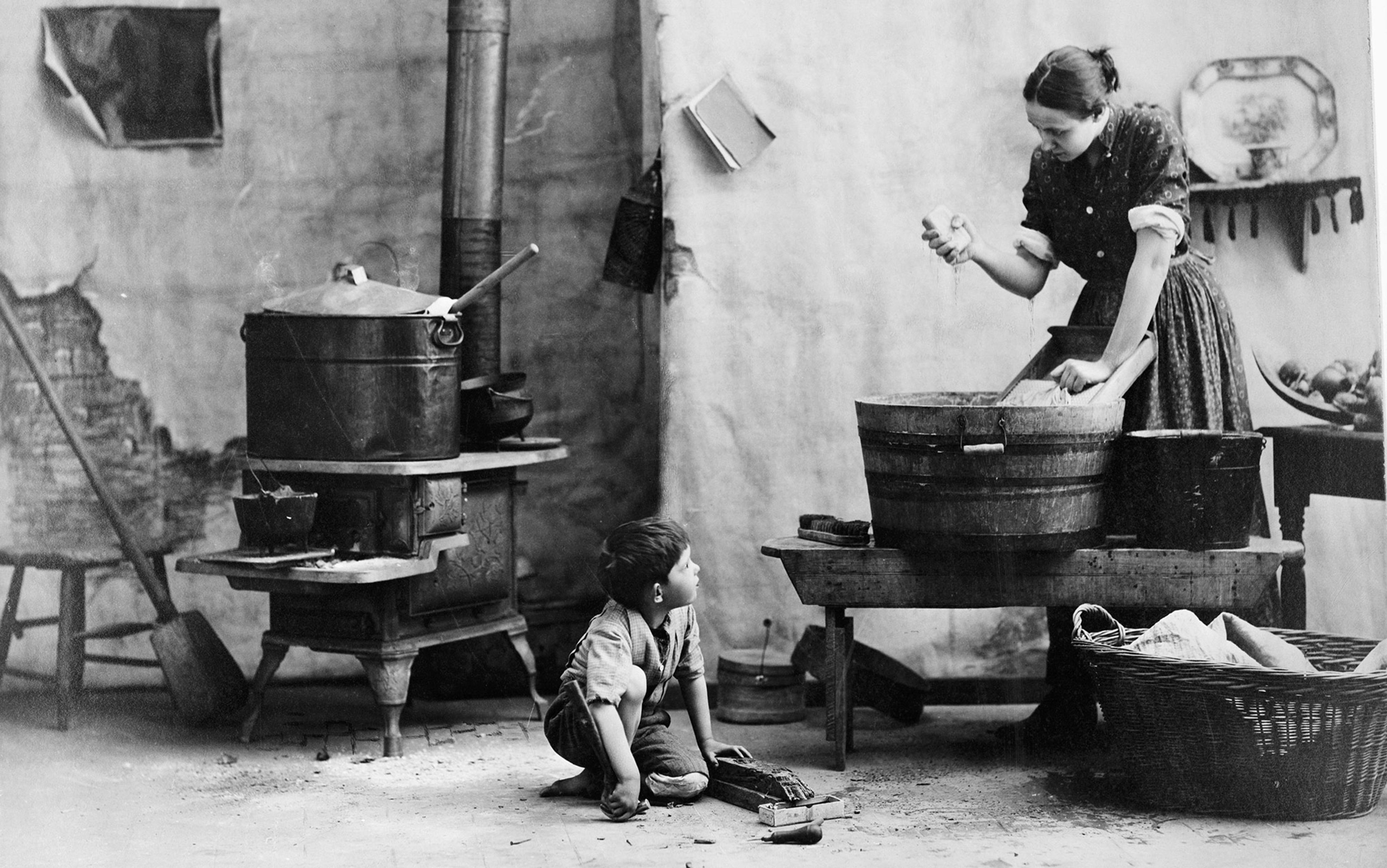

Photo supplied by the author

I used to believe that ordinary, forgettable experiences were canaries in a coal mine, warning of a complacent life. Most of the time, the acts that sustain us loop endlessly, yielding nothing that lasts: so soon, the baby needs to eat again, nap again, have her diaper changed again. The plants need more water; the clothes and dishes need another wash; we all need dinner, then breakfast, then lunch. There’s a relentlessness to daily life, an unceasing erasure of our toil and renewal of the need for more of it. In my 20s, I didn’t trust that there could be meaning in that kind of repetition. I was eager for novelty, for my world to grow large. Challenge in the outdoors was often my chosen route. On one backcountry trip, my now-husband and I split one bite of oatmeal per day after running out of food. Another time, I stayed up all night resting on spruce boughs spread over the snow, feeding a fire with branches, after a friend and I got lost in the forest. One summer, when I was commercial fishing, I lived in a wall tent. I kept my food in a cooler, but a ground squirrel kept chewing his way inside. A moment of being that has stuck: waking up to find the squirrel inside my sleeping bag. These unpleasant moments generated something for later: a story, a memory, a bullet point on my toughness résumé.

But there was something unsustainable in all that chasing. I was running on a masochistic treadmill: each cabin I lived in needed to be more rustic than the last; each bout of solitude more isolated; each trek longer and more arduous. At some point, I realised it would never be enough. The horizon would continue to recede in front of me as I lunged after ever more intensity, never getting any closer to the transcendence I sought.

I was more concerned then with having an interesting life than a good one. Now, I have a child with an intoxicating eight-tooth smile, a snug home with running water that squirrels can’t break into, a partner who, in the early postpartum days, fed me salmon-burdock soup while I nursed. But life is not as interesting, even if remote living offered me plenty of moments of non-being, too. I still baked lingonberry pie, washed dishes, swept the floor – albeit with a certain exotic ruggedness that came with the setting: I did laundry in a bucket, hauled water from the river, tended the hearth with logs I’d cut and split myself. After I married and moved to town, though, domesticity took on a different hue. I grew kale, pickled turnips and baked cookies, but now as a wife. I felt unsettled pulling long shifts in the kitchen – a discomfort that only grew when I became pregnant. I bristled when I fulfilled traditional gender roles. Was I even a feminist any more? Or was I becoming a Victorian phantom, what Woolf called the Angel in the House?

I’m often hesitant to admit how much joy motherhood has given me. Finding satisfication in domesticity feels somewhat shameful, as if I’m betraying feminism by doing what so many women fought to stop doing. Or maybe I’m afraid of betraying the more interesting, exciting person I once wanted to shape myself into. These days, I am self-conscious about using the words stay-at-home mom when someone asks what I do. Usually, I fumble and talk quickly, evasively, telling them instead about the graduate degree I’m slowly completing before changing the subject. I am afraid of seeming regressive, and perhaps boring, my mind now occupied solely by the constant calculations of nap schedules and wake windows, and questions of how much applesauce to add to a muffin recipe to replace the sugar.

Throughout my life, I’ve been guided by the principles of a lean-in kind of feminism that insists that transformation, intellectual challenge and meaning can’t happen in the home with a child. I’ve been haunted by Betty Friedan’s description in The Feminine Mystique (1963) of suburban housewives living in a ‘comfortable concentration camp’. And troubled by Simone de Beauvoir’s idea that true freedom and transcendence are possible only if we rise above our biology and social roles. This bias runs deep: in Wages Against Housework (1975), Silvia Federici describes becoming a housewife as ‘a fate … worse than death.’ In response, white, mainstream feminist liberation has focused on shattering glass ceilings and becoming #girlbosses. This has meant encouraging women of means to outsource domestic labour so they can self-actualise in the workforce, often paying more economically oppressed women to cook, clean and do childcare on their behalf. If domestic life is a concentration camp and housework is enslavement, then outsourcing it isn’t really a viable or just or feminist solution: it means placing one woman’s shackles on another. Who cleans that woman’s home? Who watches her children?

The idea of the home as a trap is not a feminist universal. As bell hooks describes in her essay ‘Homeplace: A Site of Resistance’ (1990), for many Black people, domestic spaces had a radical political dimension:

Black women resisted by making homes where all black people could strive to be subjects, not objects, where we could be affirmed in our minds and hearts despite poverty, hardship, and deprivation, where we could restore to ourselves the dignity denied us on the outside in the public world.

Here, home is a refuge, even though prioritising domesticity in lieu of paid work was seldom an option for these women. This is something Angela Davis underscores in ‘Women, Race and Class’ (1981) when comparing ‘white housewives, who learned to lean on their husbands for economic security’ with ‘Black wives and mothers, usually workers as well, [who] have rarely been offered the time and energy to become experts at domesticity.’

The same drive that led me to ski 250 miles across the Brooks Range led me to show up as a mother

Of course, women must become Supreme Court justices and senators, corporate executives and partners at law firms, physicists and wildlife biologists. But it is also vital that children are raised and fed and cared for – by someone – which means we need to value all that raising and feeding and caregiving as an essential and meaningful way to spend one’s days, too. If I’m honest, the kind of embarrassment I’ve felt at times for being a primary caretaker, or being primarily a caretaker, is because I have not valued domestic labour sufficiently.

I want to feel OK with myself, proud of myself, for choosing to spend so many of my hours tending to my child. And I want those who watch others’ children to feel dignity and pride for their work, too – and derive financial security from it. Elissa Strauss in When You Care (2024) writes: ‘It’s time to stop seeing caring for others as an obstacle to the good life and to start seeing it as an essential part of a meaningful one, individually and collectively.’ It takes work to undo the narratives that have debased this labour, though. If a younger me knew of the satisfaction I now derive from baking a soft and well-formed loaf of buckwheat bread, or having an extra giggly play session as I throw my daughter in the air and sing a nonsense song about a horse named Old Joe, she might have shuddered.

And yet these daily rhythms feel rich and alive. The same drive that once led me to ski 250 miles across the Brooks Range in winter has led me to show up as much as I can as a mother. When nursing my daughter, I didn’t want to introduce a bottle; I wanted to see if I could feed her completely from my body. Spending my days with her, without any formal childcare, has been an endurance challenge of its own. And it contains moments of being, too. When she devours that buckwheat bread and points to it vigorously, wanting more, I do feel pride; I’m meeting her needs, nourishing her body. Previously, I lunged after intensity in wild country, hoping I’d find a life near the bone, as Henry David Thoreau puts it, where it’s sweetest. Now I live close to the bone by dwelling in this intimate relationship, intense and wild as any animal or whiteout I encountered in the mountains.

Some of the resistance I’ve felt in embracing my new role – tripping up over the phrase ‘stay-at-home mom’ – might stem from internalised misogyny: I’ve looked down on traditionally feminine work. But I now see my previous bias for excitement as sexist. It is no coincidence that in my ‘danger years’ I picked up stereotypically male skills like fishing, hunting and running a chainsaw. What seemed worth doing – and remembering – aligned with activities I associated with men. I thought splitting wood and stalking beavers meant that I was interesting, unusual, strong, and feared that, in becoming a mother, I would, to quote Adrienne Rich, do ‘what women have always done.’ Nor did I think that so-called ‘women’s work’ could be interesting or stimulating. I didn’t want to cook endless dinners for a growing brood. As Felski writes: ‘Repetition is seen as a threat to the modern project of self-creation and self-determination, subordinating individual will to an imposed pattern.’ In short, I didn’t believe that the Sisyphean tasks of the home could be a path to sucking out the marrow in life.

Before motherhood found me, I read books that focused on maternal resentment and rage, the push and pull of trying to be a mother and anything else at the same time. What I learned from them is that I would lose my freedom in having a child and resent my husband for the asymmetry of our contributions to domestic labour. I expected that I’d fantasise about bolting. Rachel Cusk’s writing on motherhood is laced with the language of imprisonment and slavery. And, in Of Woman Born (1976), Rich confessed: ‘My children cause me the most exquisite suffering of which I have any experience.’ I feared ending up like the middle-aged woman disparaged by Martha Quest in Doris Lessing’s novel A Proper Marriage (1954) ‘who had done nothing but produce two or three commonplace and tedious citizens in a world that was already too full of them.’ Lessing famously left her own two children, fleeing them and the ennui she felt as a mother, climbing what she called the ‘Himalayas of tedium’.

I loved these books for resisting maternal sentimentality in order to tell a more nuanced and taboo story. They convey daily reality and label the cycles that fill many women’s lives. Importantly, they push back against the previously dominant narratives of maternal bliss. In an article for Vox magazine in 2023, Rachel Cohen Booth argues that in liberal circles and among millenials the new dominant narrative about motherhood has become one of dread. Cohen spoke to Leslie Bennetts, author of The Feminine Mistake (2007), who feels that unvarnished representations of motherhood are ‘a necessary corrective to all these sugar-coated unrealistic fantasies, but we have gone too far.’

Books about ambivalent motherhood have resonated less with my personal experience than I expected

Of course, there are still many sugar-coated narratives of family life out there, especially prevalent under the #tradwives banner and among other influencers on Instagram and TikTok who document themselves making marshmallows from scratch or pausing their bread-making with children to milk the sheep. Because I do not share the religious or political beliefs of many of these women, I expected to feel repulsed by their vlogs, but when I’ve pulled up some #tradwife accounts that portray the rhythms of farming, cooking and caretaking, I have instead felt discomfited by my own interest in the content. The videos often exalt the non-being of daily life: their reels make domesticity glamorous, elevating my own days making almond-flour cookies and miso-glazed salmon with a baby on my hip, even if my version looks significantly less put-together.

Since having a child, books about ambivalent motherhood have resonated less with my personal experience than I expected. Yes, the sleep deprivation has been trying. Figuring out the division of labour with my husband can be maddening. And being home with a small child is sometimes tedious and isolating. Yet my life has had more joy, song, purpose, camaraderie and focus than before. More ambivalence might lie ahead – after all, I am only a year into motherhood – but, so far, I find a lot of everyday domesticity life-giving and generative. I like pickling vegetables. I like making soup. I like digging my fingers in the soil and wresting a carrot from the ground. I don’t want to drink Soylent and stare at a screen; I want to taste frost-sweetened root vegetables, lick wild blueberry juice off my fingertips, suck the fat off salmon collars. I’ve also learned that I want to feed those carrots (and berries, and salmon) to my baby. I want to eat with her as she slathers yoghurt and chia seeds across her face, to show her the ravens playing in the trees and the full moon rising in the sky, and to sit with her as she leaps on our two dogs and yells out ‘da da da’. Not only do I like all this; I don’t want to miss it. Even if I remember very little, even if it blurs into a beige smudge of non-being, I want to be as close as I can with her during these early years. In the material, visceral, embodied world of this present.

I still struggle with the idea of forgetting all this wonderful non-being. It goes so fast, everyone says. I don’t want to forget how today I bounced the baby in the carrier on our neighbourhood trail, shushing in her ear, seeing the birch trees sway overhead, the wind rustling their leaves. Or how later I curled my body around her in bed as she nursed, held her soft head in my hand, placed my cheek against her silky hair. Sometimes, I write down these little moments to forestall the forgetting, as I’m doing now, trying to resist erasure by writing this essay. Here I am, again, turning the present into something for later. But now it’s the non-being I’m attempting to preserve rather than only ‘moments of being’. Perhaps this rescue mission animates internet vloggers, too, #tradwives included, in recording the quotidian so obsessively: the shortbread lasts only so long, but sharing the content is a way of preserving it after the last crumb has been consumed.

Woolf’s moments of being and non-being have long been a guiding principle for me, yet now that I return to ‘A Sketch of the Past’, I realise that I was the one who carried a bias against non-being – not Woolf. She held a deep interest in non-being, believing it made up a great deal of life, and was worthy of attention and study. Woolf wanted her writing to get ‘closer to life’, to portray the kinds of everyday moments we all experience then almost immediately forget. In her fiction, she devoted her literary talents to repetitive and uneventful experiences, especially those of women. As the literary critic Liesl Olson writes, ‘it is possible to understand her entire oeuvre as committed to the representation of the ordinary.’ Another critic, Chiara Briganti, describes Woolf ‘rescuing the quotidian from anonymity, salvaging the constant flow of life jetsam that “falls through the narrative sieve”’. This is what contemporary motherhood narratives are trying to do, too. In a way, it’s what I’m trying to do, as well, while I sit here typing as the baby naps, glancing at her on the video monitor, hoping to capture in words the hours we’ve shared before they drift out of reach.

Part of Woolf’s project involved resisting the idea that only exciting events make for meaningful stories. Her essay ‘Modern Fiction’ (1919) is a call to action for writing to bridge the gap between our experiences of life and the stories we tell about it: ‘Let us not take it for granted that life exists more fully in what is commonly thought big than in what is commonly thought small.’ She understood that what we think of as ‘big’ versus ‘small’ often falls on gendered lines. In A Room of One’s Own (1929), she says:

[I]t is the masculine values that prevail. Speaking crudely, football and sport are ‘important’; the worship of fashion, the buying of clothes ‘trivial’. And these values are inevitably transferred from life to fiction. This is an important book, the critic assumes, because it deals with war. This is an insignificant book because it deals with the feelings of women in a drawing-room. A scene in a battle-field is more important than a scene in a shop – everywhere and much more subtly the difference of value persists.

This contrast between the important and the trivial is split between several binaries: women versus men; the event versus the everyday; the home versus the public stage; and, not least, what sticks in our memories and what falls through the narrative sieve.

I thought I needed to do something exotic in order to have something to say

In my 20s, the books I treated as lodestars steered me toward solitary adventure and self-imposed hardship. They were often about white men heading out on journeys to find themselves: hitting the road, isolating themselves in cabins, scrambling up peaks. I thought of Edward Abbey wrapping snakes around his waist, or Japhy Ryder running down a scree slope, or Thoreau fantasising about seizing a woodchuck. Like these author-heroes and their fictive avatars, I, too, wanted my days woven into wild landscapes, danger and surprise always lying in wait. Woolf’s writing does something else, though: it captures the wild wanderings of a human mind in the home, as elsewhere. Her characters’ thoughts travel as they serve soup, knit socks, mend dresses. By attending to the granular reality of women’s daily lives, and treating them as worth representing in fiction, Woolf made women’s existences significant, too. Woolf wanted things both ways: she advocated for women to have more access to education, financial independence and choice, but her fiction also sang with their everyday experiences, portraying the small moments that otherwise dissolved into nondescript cotton wool. Her way of recognising the worth of domestic labour was to render the invisible more visible, highlighting the creativity and interiority present in those quiet domestic activities.

Now I think that my youthful longings for a life worth recording, at least by the standards of a society that derides the looping lives of so many women, stemmed from a desire to generate writing material. I thought I needed to do something exotic in order to have something to say. Yet Woolf’s work demonstrates that it’s all already here, that even the most mundane tasks of daily life can be sources of interest. Writing has long been a way for me to pay closer attention to life, but I have often lacked the imagination to find stories from within the everyday. I am trying now. Jotting down the activities of my days helps me see them – picking clothes and toys off the floor, making another sheet pan of roasted beets and carrots, rolling over in the middle of the night, lifting my shirt, and stroking her back as I hum: Sleep, sleep baby sleep. But I am not doing these things to generate writing material; I am doing them because I want to be there for my daughter. She’s still so young she won’t remember this devotion; she won’t know I gave her an infant massage before bed, or held her in the wee hours of the morning when she cried. I trust that my presence and actions have an impact, but I have to remind myself – again – that the value of an experience doesn’t reside only in how we look back on it in the future, or how we later tell it in a story.

It’s similar with cooking. I rarely remember a good meal, but every now and then a dish stands out. A cashew-ginger sauce for a farro bowl; potato pancakes with nigella seeds and lime. Food is about the present tense – those ephemeral moments between chew and swallow. Soon, all the hours of chopping, roasting, sautéing – and sometimes, sowing, watering, weeding and harvesting, or catching, cleaning and filleting – disappear. Taking care of a baby is like that, too, entirely present. My eyes lock with hers, she babbles with a scrunched-nose smile, we giggle, and I try to discern whether she’s all done or wants water or milk or more lentils. It’s like a sand mandala. The point is to work hard then let it go.

Finding contentment in everyday experience offers a sturdier version of happiness

Woolf wrote in her diary:

The immense success of our life, is I think, that our treasure is hid away; or rather in such common things that nothing can touch it. That is, if one enjoys a bus ride to Richmond, sitting on the green smoking, taking the letters out of the box, airing the marmots, combing Grizzle, making an ice, opening a letter, sitting down after dinner, side by side, & saying ‘Are you in your stall, brother?’ – well, what can trouble this happiness?

Finding contentment in everyday experience offers a sturdier version of happiness – harder to trouble – than a happiness that might make a more exciting story, yet it depends on more elusive experiences, like exultation, ecstasy and transcendence, which is why Woolf names the enjoyment of these common things a ‘treasure’. Eating a meal or performing daily tasks might not sparkle as brilliantly as a heroic tale from war or a traverse across glaciated mountains, but there we can still find the true gold of life. And we don’t have to chase anything; those experiences are already here.

Of course, the pleasures of dailiness are not always enough to forestall anguish. Before she drowned herself, Woolf scribbled a note to her husband, Leonard, saying: ‘You have given me the greatest possible happiness. You have been in every way all that anyone could be … I don’t think two people could have been happier than we have been.’ Yet she’d relapsed into the kind of acute depression reminiscent of a mental breakdown she’d experienced about 25 years before and from which, this time, she did not think she could recover. Still, as she reflected on her life, it was her marital happiness that she celebrated – even if she so often forgot what she and Leonard talked about at tea.

I have bouts of anguish at times, too. On one recent night, sleep deprivation and some fights with my husband coalesced into despair. In the rocking chair, I read to the baby through tears: ‘Good night room. Good night moon. Good night cow jumping over the moon.’ My voice shook. She reached for the book. I wanted to wallow. I wanted to lie on the floor and thrash and cry. But I couldn’t. I had to take care of her, nurse her, stroke her back, sing her to sleep. And the next day, I had to change her diaper, brush her little teeth, offer her carrots and salmon. I had to change her diaper again, put her down for a nap again, nurse again, all of it again and again and again.

In the end, all of this non-being, all of these everyday repetitions are the necessary, life-giving stuff of my life. Lately, I am finding that it saves me: not despite being mundane, but because it is mundane – constant, renewing, needed. I am (gradually) learning how to find the treasure right here, remembering Annie Dillard’s insight that ‘How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.’ When I show up for ordinary moments, without worrying about turning my experiences into stories for later, they can be a source of joy and interest, even inspiration. Day after day, they root me here, among the living.