I can hear weeds growing outside. I can hear my pores clogging. I can hear dust settling on the furniture. I can hear an ant finding its way under the back door. I can hear my arteries hardening. You try to prevent these things from happening, but there is no escape. Paint peels from the baseboards; the refrigerator hums, waiting to break; sunlight sears a faded spot across the rug; peaches grow soft and mouldy in a wire basket on the counter.

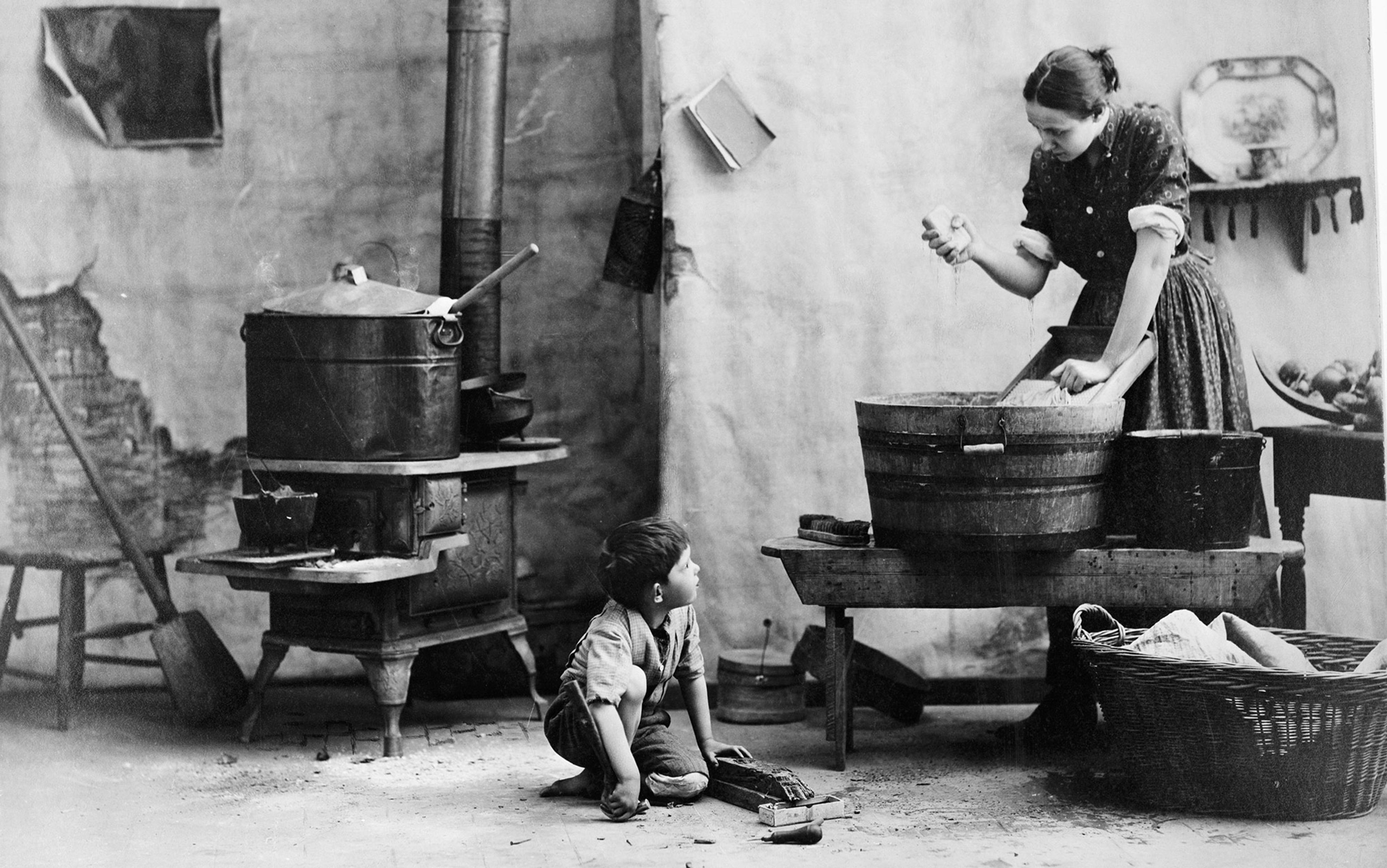

And then there is the dirty laundry. Even as I am sleeping, dirty laundry fills hampers and overflows the sides, scatters across the floor, and begins its inexorable trek toward the washing machine.

Nothing embodies the domesticated adult’s powerlessness quite like dirty laundry: its awesome flow through the home, a colourful river of little mud-spattered pants, stained dresses, greasy placemats, and musty towels. I might unclog a few pores, I could smash one or two ants, I can throw out the mouldy peaches, but trying to staunch that flow of dirty laundry is like trying to stop the flow of a river to the ocean. When I attempt to build a dam, the gods rain down more dirty laundry, and my dam breaks. Dirty laundry is eternal: it knows no boundaries.

We learn a lot about ourselves, about our plight in life as former free spirits who mutated into heads of household, when we gaze into that crashing river of dirty laundry that rushes through the closets and hallways of our habitat. Do we feel powerless, when we finally recognise that we’ll never truly conquer it?

Here’s how it is. One day, you’re sitting there, reading a good novel or watching something ridiculous on TV. The next day, you’re racing around the house, frantically wiping up spills, doing dishes, changing diapers, reading that goddamn pigeon-driving-the-bus book for the millionth time in a row, and you’re running behind. You’re always running behind, in fact. The fridge is empty, the kids are hungry, the floors are filthy, the bed is unmade, the dogs are restless, and all you and your husband want to know is: can we pay someone to do all of this taxing work so we can get fall-down-drunk on margaritas instead?

And it’s almost comforting, to think that you could just hire someone and then go get wasted, as is your birthright. But whom could you possibly pay to tame the wild and turbulent surging of dirty laundry through your house? No mortal could be hired for this purpose, and thinking otherwise is an exercise in fantasy. In truth, there is no escape. You will be running around in little circles, spraying stains and emptying pockets for the rest of your life.

You can feel your own mortality there, among the filthy socks and leggings with muddy knees

Yes, it’s true that every now and then, you stop and say: ‘There. I did the laundry. The laundry is done.’

You are a fool. For even as you speak the words, the hamper is filling up. Saying ‘The laundry is done’ is like saying: ‘There, I am old. I am all done ageing.’ No. Just as you will get older and older until you die, you will always have laundry to do. Are you wearing clothes right now? That’s more laundry that needs to get done. Short of ditching your family and moving, all alone, to a remote nudist colony in the tropics, there will always be more dirty laundry.

Sometimes I think of the old days, when laundry was just something I shoved aside, peeling off this top that smelled like an ashtray after a night out at a bar with friends, or tossing these shorts, sweaty from a morning jog, toward the hamper.

The hamper filled slowly back then. One dirty towel added, one bra, one pair of pants. After a month or so, it would finally overflow and I’d load up two giant suitcases and head to the laundromat. There I’d empty everything into two industrial machines, then sit and read for a while. Laundry was just an excuse to leave the house and finish a good book. It was just a task I figured I wouldn’t do anymore, once I got rich.

Ha, ha! Remember how we were all going to get rich some day? We were so full of possibilities, weren’t we, back when laundry was discrete, limited, bounded by space and time.

You can feel your own mortality there, among the filthy socks and leggings with muddy knees. Once, you imagined that your life would be unfathomably glamorous. Why did you ever think that, again? What gave you the idea that you might live effortlessly in some spotless expanse of sunshiny wood floors, with healthy plants thriving, nice-smelling meals being cooked by someone else, and babies toddling about adorably?

Instead, your children wade through enormous piles of dirty laundry, and proof of your inadequacy is everywhere. Five wet washcloths hanging on the shower curtain, two pairs of dirty socks under the dining room table, four crumpled dresses on the bedroom floor. These soiled artefacts embody the trivial chores that will fill up your balance of days on the earth, preventing you from achieving greatness.

This is the strange gift that laundry brings to our lives. Its sheer mass, its magnitude, its ceaselessness make us aspire to greatness

Of course, back when you were single and untroubled by laundry, were you actually progressing steadily toward greatness? No. You were trying to decide whether to order the pastrami or the roast beef for lunch, or you were getting your hair highlighted while flipping impatiently through a heavy fashion magazine, or you were neurotically reviewing your drunken conversation with a guy you met the night before for clues as to whether or not he was interested.

But this is the strange gift that laundry brings to our lives. Its sheer mass, its magnitude, its ceaselessness make us aspire to greatness, even as such aspirations become less and less possible. When faced with such awesome power, we want to rise up, to harness the best within ourselves, to create something inspiring and wise! Why, then, must we spray stain remover on this little white smock instead? Why must our brilliant thoughts lie fallow, as we gather armfuls of laundry from hampers? One thing stands between you and the enviable career, the lasting legacy that you so richly deserve: dirty laundry.

Dirty laundry also prevents you from communing intimately with your spouse. Surely you’d be uncorking a nice bottle of red, pouring it into glasses, and having a gentle and rambling talk about your day, if not for the numbing, impenetrable nothingness of piles of clean laundry, those folded stacks crowding you on your own bed, rendering impulsive affectionate gestures or intimate touches an impossibility.

Children can’t be seen or heard, either, since they’re usually surrounded by dirty laundry. Sure, you would stop and give this one a little squeeze, or flash that one a smile, but, alas, there is laundry to be done.

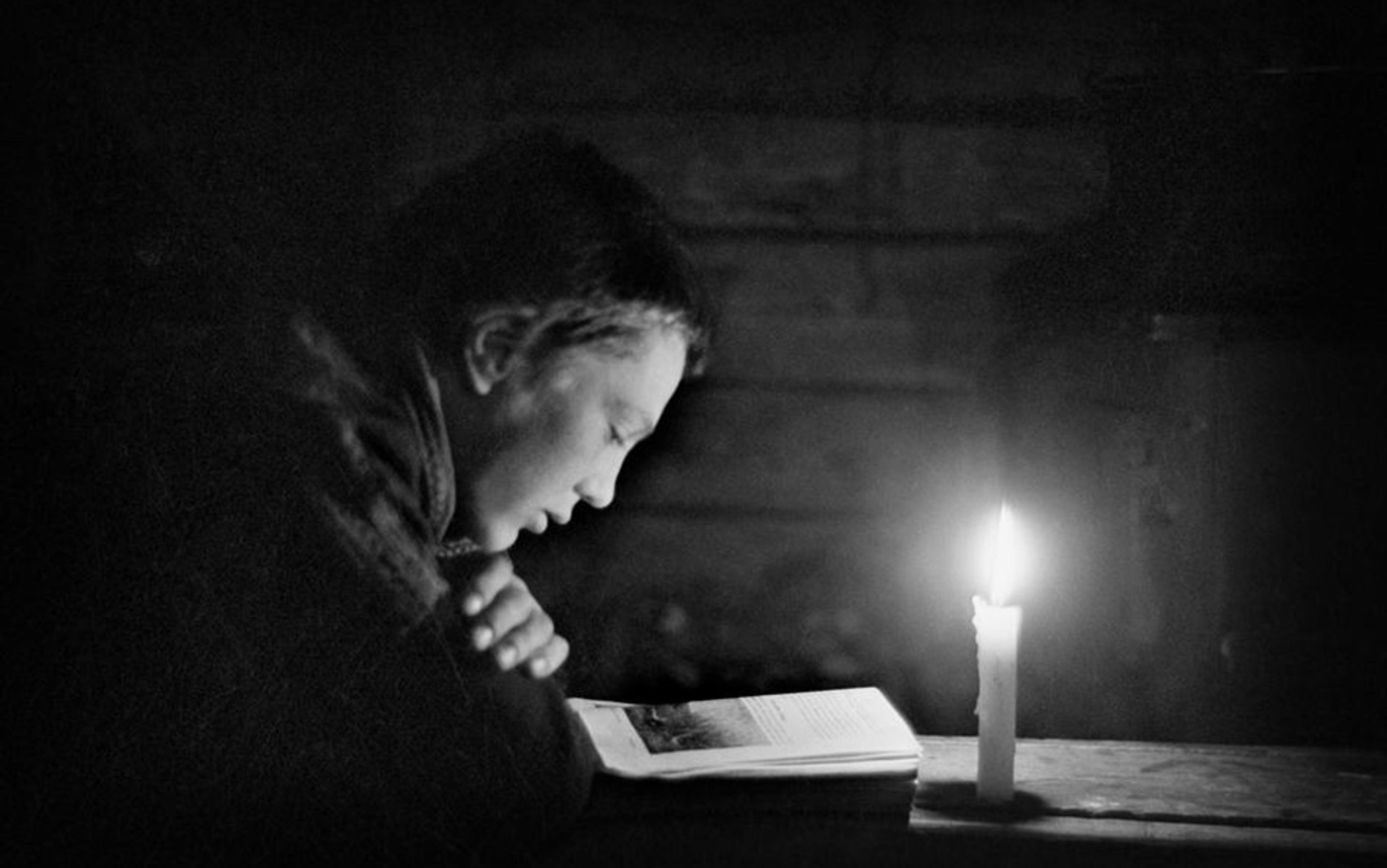

You awake before sunrise, hoping for a little time to yourself, but then you spot something: a pile of napkins from last night’s meal, cluttering up the hallway. You do your best to ignore it, but when you sit down to work, the image dominates your mind. No calm moments can be yours, with such soiled things creeping about, even in the dark of night.

How can you leave the house, with so much laundry to do? Isn’t going out a little stupid, when you consider how far behind you’ll be on laundry? Why do anything, really, when it’ll only get interrupted by a washing-machine buzzer?

The other day I watched a bear on a bicycle chase a monkey on a bicycle, in a YouTube video shot at a Shanghai circus. First the bear and the monkey pedalled furiously at opposite ends of the ring, riding in a circle. Slowly, the bear starting gaining on the monkey. Finally, the bear caught up to the monkey, crashing his bike into the monkey’s bike. Then the bear ate the monkey.

One circus trainer yanked at the bear, trying to rip the monkey out of its claws, but this was obviously wasted energy. Another circus trainer stood and watched, but did nothing. Both circus trainers must have known how this story would end the day they bought that bear a bicycle. How many times did the bear dream of feeling that monkey between its jaws? How many nights did the monkey lie awake, worrying about it? By the time the monkey found itself inside that bear’s jaws, it must’ve felt like sweet relief, like salvation, a deliverance from lifelong suffering.

The laundry will never be done. It doesn’t mean anything. Rather than pedalling faster and faster, the only answer is to surrender to the eternal tide. My life is no longer turgid with possibility. It is turgid with trivialities instead. But is there really that much of a difference between the two? Stare into that rushing river of textiles and ask the gods: ‘Why does it matter what I do? Who is watching, anyway?’

My children just look at me. Maybe their mom is a little unhinged. That’s OK. They’ll understand eventually

We all have an undetermined number of days left on the earth, and there’s not much we can do to extend them. We have children who will grow up to be depressed or happy or resentful or generous, and we can’t form them like clay or guarantee that they’ll turn out one way or another. We have the things we have, rich or poor — or, like most of us, somewhere in the insecure in-between. Our windows are clean or dirty, our rugs are vacuumed or covered in dog hair, our closets are a mess or well-ordered, there are dirty dishes laying about or not. These things don’t define us, no matter how stubbornly we cling to the notion that they do.

‘Relax, you’ll die poor,’ someone wrote somewhere the other day. And it’s true: I’ll never have all the money and all the time in the world, to go anywhere or do anything. And even if I did, I’d probably still stay right here anyway, worried or overwhelmed or distracted by something unimportant.

So instead, I will resolve to complete these repetitive tasks without wondering why, without wishing someone else would do them for me. Instead of viewing the chaos, the filth, the messes, the dirty windows, as a reflection of my ineffectual self, I will choose to see them through some kind of Zen, accepting haze. Instead of sorting and folding clothes faster and faster, maybe I’ll try to sit down for a second, and think about where I am and what I have. I have a house filled with dirty clothes. I have a machine to wash them in. I have big windows to smudge up. I have crazy dogs shedding all over my dirty floors. I can’t prevent the next mess, or clean this one up fast enough.

What kind of small mind fixates on trivia, when the world is filled with so much beauty, and so many opportunities to love and be loved? Why run around making things look clean, when you can leave the dishes in the sink and order a pizza and eat it on the couch with the kids in front of the TV set, even though that’s supposed to mean you’re a bad parent, even though American Idol isn’t exactly educational programming? So what? Doesn’t that one girl make me cry every time she opens her mouth to sing? Doesn’t her voice change everything? And when my kids ask me why tears are rolling down my cheeks, I tell them that when someone can focus like that, with an open heart, with a calm mind, it’s like they’re channelling some divine force. There is nothing quite like that moment, I tell them, when you realise that you’re very small, that you’re not in control, but the grace of the whole world, the spirits of the dead, are rallying around you. In the soaring sound of her voice you can hear it: the sky is on her side.

My children just look at me. Maybe their mom is a little unhinged. That’s OK. They’ll understand eventually.

In the meantime, I will sit here, listening to the weeds growing outside, listening to my pores clogging, listening to the dust settling on the furniture, listening to the ant finding its way under the back door, listening to my arteries hardening. I will be still, letting the paint peel from the baseboards, letting the refrigerator hum until it breaks, letting the sunlight sear a faded spot across the rug, letting the peaches grow soft and mouldy in a wire basket on the counter. I will let these things happen. And it will feel good to be alive.