Holes are full of potential. We can only imagine what was in them before they were emptied out, why they became nothing instead of something. Like a kaleidoscope, the picture made by holes is always changing. Like history or art itself, holes are never finished. Archaeologists use soil analysis to identify postholes, the marks of ancient settlements. They excavate sewers at the Colosseum to find things the Romans thought not worth writing about. Holes leave space for projecting both forwards and backwards in time.

Museum and library collections are full of holes. Some are the product of hungry bookworms and moths. Others are deliberate, made by humans. These holes are, arguably, the most crucial bits, even though they are missing. This is the hole’s paradox. A hole points, through absence, to importance. The object wasn’t just used; it was used up. Philosophers struggle mightily over this question: is the hole something or nothing at all?

In his small artist’s book Hole Theory (2002), the American artist William Pope.L lays out the case for holes. The spiral-bound book is annotated with handwritten notes (denoted here by square brackets) and the text is crossed out in places, making its own black holes on the page. In this text, which is a hybrid poem-manifesto, Pope.L embraces the paradox of the hole:

Hole Theory presupposes

That there is possibility

Even in the face of nothing …

He concludes:

… this theory

Could only come from someone

Who lacks something

As a political condition.

[…] Hole Theory engages lack

Across economic and cultural

And political boundaries.

He adds, in pencil, overlaid with purple highlighter: [‘LACK IS WHERE IT’S AT.’]

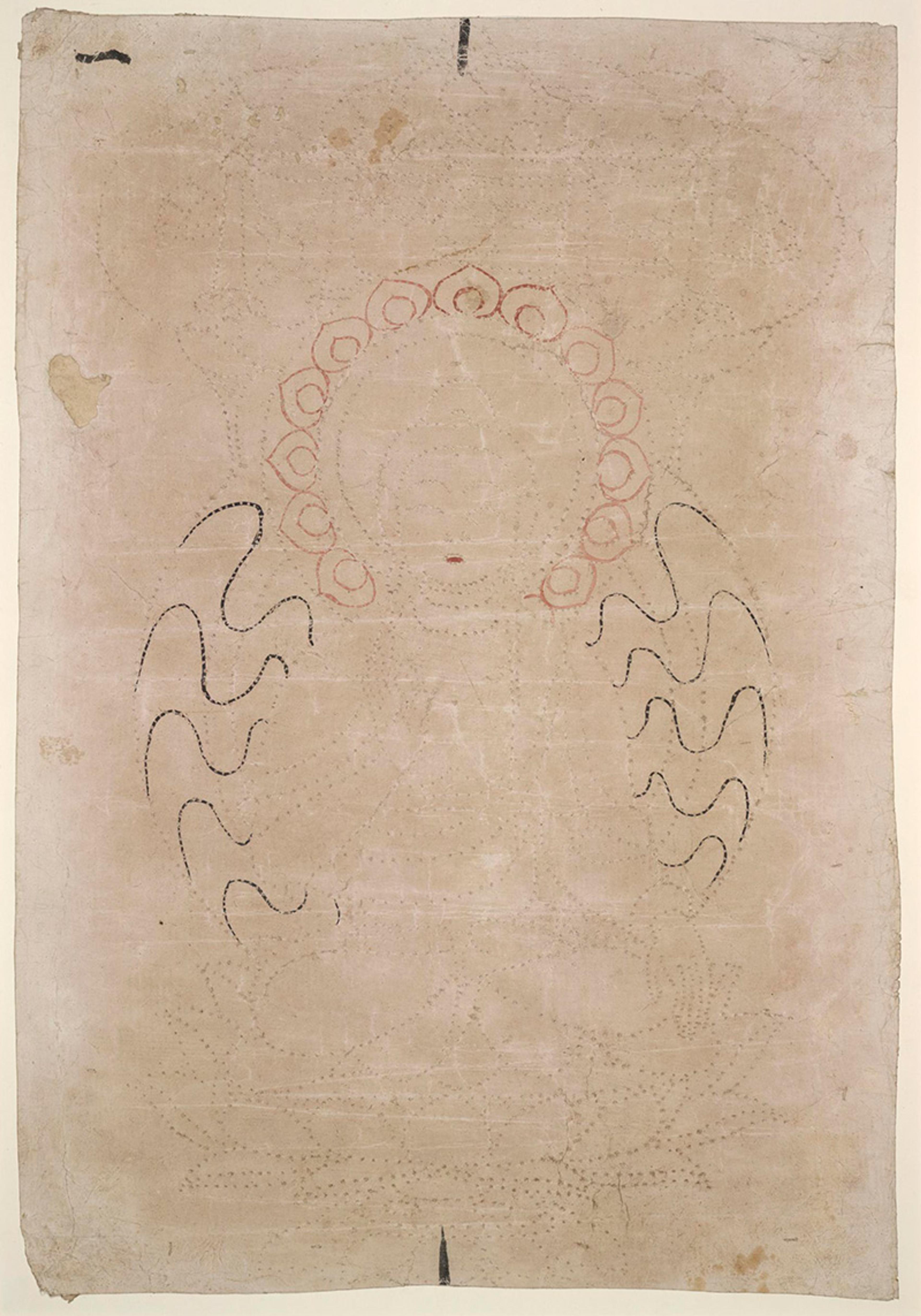

Some of the oldest intentional holes in art museum collections were used to create more art. Holes can be generative. In a technique known as pouncing, artists or their assistants would poke tiny holes in the lines of a drawing, then lay it flat on top of another surface. By dusting the pin-pricked drawing with charcoal or crushed black chalk, they transferred the image to another sheet, a wall, or repeated on fabric. By placing a blank sheet below the drawing to be copied, assistants could make an intermediary copy, which saved the original drawing from obliteration by charcoal clouds.

Pouncing likely originated in 10th-century China, as evidence of pin-pricked drawings found in the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas at Dunhuang suggest. These drawings were used to create murals, but pin-pricked paper stencils could also be used to create repeating patterns by copying a design multiple times. It’s thought that the practice travelled the Silk Route to Italy after Marco Polo’s return to Venice in 1295. It was first described in Europe around 1390 by the Italian painter Cennino Cennini who recommended it for creating patterns on gold brocade.

Stencil for a Buddha, Chinese (c926-975). Courtesy the Trustees of the British Museum

During the Italian Renaissance, pouncing was used widely to transfer a master’s sketch from paper to the wet plaster of a frescoed wall. Raphael was especially known for the use of pouncing in his workshop. Surviving drawings reveal holes poked along all the major lines and they show his use of both sides of a sheet, as the holes sometimes interrupt a drawing on one side in order to copy the drawing on the other. Even though they were seemingly destroyed by holes, Raphael’s pounced drawings were carefully preserved by his workshop.

The Adoration of the Shepherds (c1499-1501), attributed to Raphael. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Studies of the heads of two apostles and of their hands (c1519-20) by Raphael. © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Pins and their accompanying holes are found in old books, too. The Bodleian Library in Oxford can date some of their collection’s pin-holes to the 15th century. Before staples and paperclips, straight pins were used to repair bindings and hold loose pages together. Pins were frequently used as bookmarks and for editing. Jane Austen pinned paper patches to the unfinished manuscript of her novel The Watsons in order to add new sections of text.

Only in recent years have holes been routinely catalogued, alongside other reader’s marks

Pins were also used as tiny pointers, highlighting letters or words in books for children who were learning to read. Patricia Crain, a historian of early children’s books, notes that ‘occasionally one comes upon pages with the pin pricks still visible’. The hole points to something necessary, even as it marks its absence.

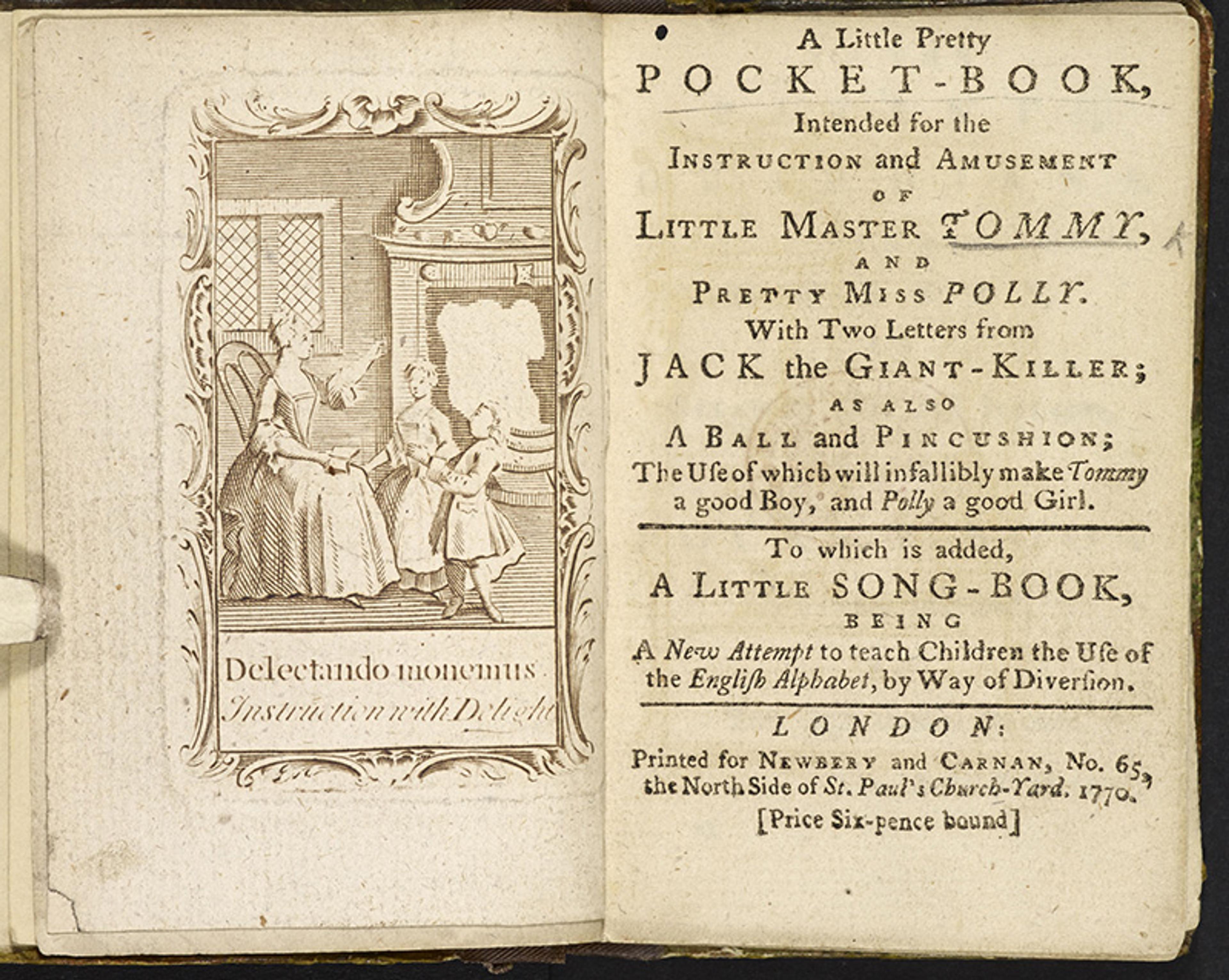

The humble pin was an all-purpose instrument, widely available in Europe by the end of the 17th century and ready to hand, especially for women and girls who wore them in hats and used them for sewing. But Caroline Duroselle-Melish of the Folger Shakespeare Library cautions that finding a pin in a book doesn’t necessarily mark its owner as a woman. Although women were the chief consumers of pins, pins were used by men, too, even from childhood. A black-and-red pincushion was sold with John Newbery’s 18th-century book for children, A Little Pretty Pocket-Book. Young girls were expected to mark their good (or bad) deeds by putting a pin in either side of the pincushion. For boys, a two-tone ball accompanied the book, also ready for pins. The title page promised that this embodied practice of learning would ‘infallibly make Tommy a good Boy, and Polly a good Girl’.

Title page from A Little Pretty Pocket-Book (1770) by John Newbery. Courtesy the Trustees of the British Library

Another late-18th-century children’s book personified the pin: The History of a Pin, as Related by Itself. The title character introduces itself:

I began my career in life with the best hopes and fairest prospects; I had a good head, and was prepared by various hands with sharp qualities, to make myself useful in the world.

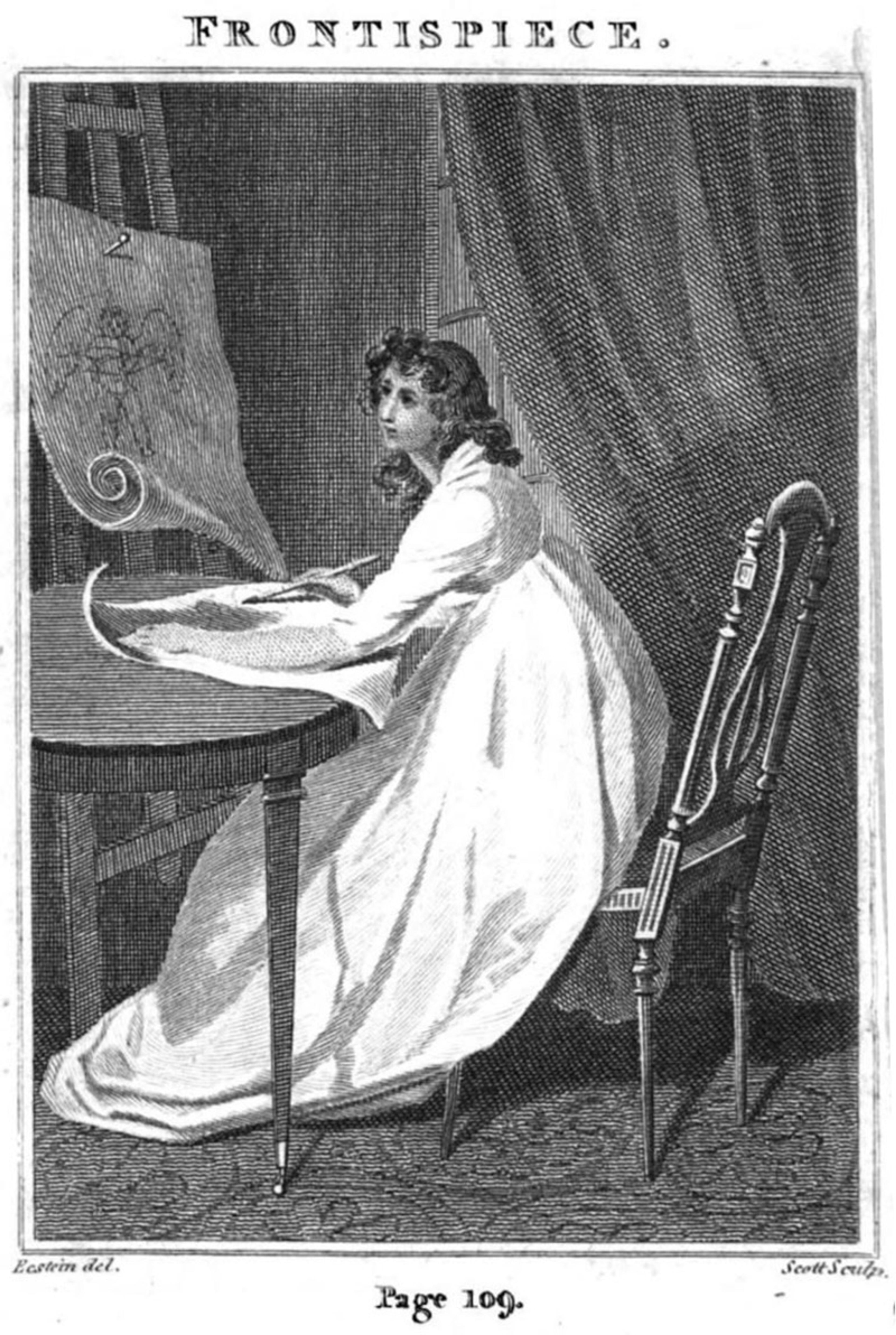

Owned by a woman, the pin participated in the mistress’s work of educating her children, as was common in the 18th century. The pin admits that it hadn’t much formal education itself, but ‘no one was better able than myself to point out the beauties and useful part of language to the young learner. It was my business particularly to teach the youngest child her letters,’ in a reference to the use of pins as pointers. The frontispiece bears a portrait of the pin, although it takes a while to identify. A young woman seated at a parlour table is drawing from a print of an angel. Upon close inspection, the object of her attention becomes clear; the woman gazes admiringly at the pin holding the paper in place on the easel.

Frontispiece of The History of a Pin, as Related by Itself (1798) by Miss Smythies. Image supplied by the author

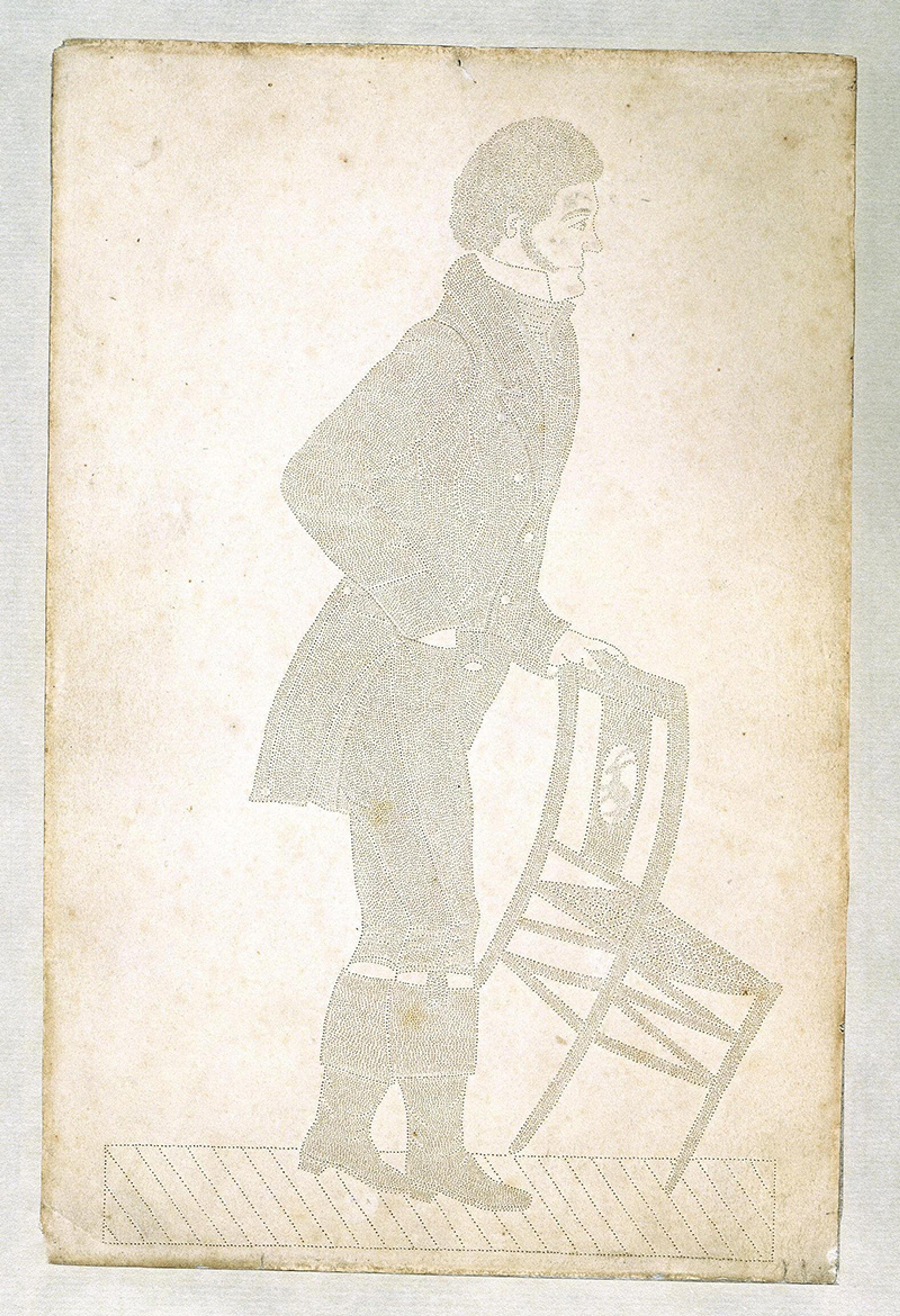

Holes became their own art among genteel women of the late 18th century. Pin-prick pictures were a popular craft, created by poking holes in paper. The image was the result of the play of light and shadow. Sometimes these pin-prick pictures appeared in books. The American Antiquarian Society has at least two volumes that were decorated with pin-prick pictures by distracted readers.

Pin-prick picture (c1830), bequeathed by Mrs E Bardsley © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Searching for holes in books may be harder than finding needles in haystacks. Holes cannot be removed and collected like pins. Holes remain distributed, housed in their original pages. Only in recent years have holes been routinely catalogued, alongside other reader’s marks such as underlining, in collection databases. Holes were long thought to devalue rare books. However, collectors and scholars have taken new interest in reader’s marks since the mid-1980s. These marks, which are not always related to the text – penmanship exercises, shopping lists, calculations, correspondence drafts, recipes – reveal a host of behaviours that are coincident with books, even if not evidence of reading the text at hand. In this changed scholarly climate, holes take on new significance.

Holes are foundational to the optical principle that gave rise to photography. Light passing through a hole in a lens will project an image of the outside world onto light-sensitive material hidden within the camera. A small aperture in a darkened room creates the same effect. The world reproduces itself, in all its colour and motion, on the wall inside. For Leonardo da Vinci, this trick of physics was nothing short of miraculous. He wrote about it in the Codex Atlanticus (1478-1519):

Who would believe that so small a space could contain the images of all the universe? […] This it is that guides the human discourse to the considering of divine things.

Here the figures, here the colours, here all the images of every part of the universe are contracted to a point.

O what point is so marvellous!

This point of light echoed Leonardo’s work as an artist. In the hole, the Universe drew itself. It’s as if the visible world was pushed through a sieve and came out the other side, strained into its purest self.

Nearly 500 years later, Roland Barthes’s theory of the power of photography also hinges on a pin-prick. In Camera Lucida (1980), Barthes designates a Latin word to stand for the sharp, personal experience of photographs: punctum. He describes the punctum as a

sting, speck, cut, little hole – and also a cast of the dice. A photograph’s punctum is that accident which pricks me (but also bruises me, is poignant to me).

He doesn’t find a hole in the picture. Rather, there’s something that rises up from the photograph, ‘shoots out of it like an arrow, and pierces me’.

These affective, wounding elements are never intended by the photographer; they are always accidents, according to Barthes. It’s not the general meaning of the photo – horror of war, familial love, or a photographer’s lucky find – that Barthes sees in many popular images. The punctum is something small, inessential to the scene, likely unnoticed by the photographer. It speaks directly to a viewer’s personal experience or memory. Barthes points to the fingernails of one subject or the necklace of another. These are the small, incidental things that move him. The photograph creates a hole in the viewer.

The hole is meant to obliterate, but instead it draws attention, like water down a drain

Sometimes, a photograph is too powerful. A hole is cut in it, as if to deflate its power. A face is snipped out, torn or erased. Family photo albums preserve holes like these. They may include light-hearted captions, such as ‘this is an outline of me’ or ‘omitted by request’. But, uncaptioned holes can be just as loud. Two women on a tandem bicycle, bound together in the frame. A small, erratic hole removes the head of one, the torn edges like a halo of hair. On the photo’s verso, nothing but the photo finisher’s stamp from Minneapolis and the date: ‘JUL 24 1940’. Who was she? Was her erasure immediate or retroactive? Another example: a little girl in a baby-doll dress posing outdoors with an older boy. He holds his hands neatly behind his back; his head is carefully cut out of the frame. The hole is meant to obliterate, but instead it draws attention, like water down a drain.

‘This is an outline of me.’ Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The tandem, Minneapolis, July 1940. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Boy and girl. Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

Recently, a particular set of holes has attracted the attention of artists and writers. During the economic depression of the 1930s in the United States, photographers hired by the Resettlement Administration, later the Farm Security Administration (FSA) – a federal agency of the New Deal government – created tens of thousands of pictures showing the impact of drought and migration on labourers. These photographs were at first meant to demonstrate the need for government assistance programmes, then to celebrate the success of such programmes. The head of the FSA’s Information Division, Roy Stryker, punched holes in the negatives that didn’t serve these purposes. Of the 145,000 images made, about 68,000 were considered rejects and 4,200 of these were hole-punched. The practice was dubbed ‘killing’ a negative.

In 2018, the Whitechapel Gallery in London hosted an exhibition of prints made from scans of the hole-punched negatives, alongside work made by contemporary artists in response. Press materials described the re-presentation of the killed negatives as ‘transform[ing] an act of censorship into abstract, conceptual and strangely beautiful pictures’. Articles in the popular press both preceded and followed the gallery’s attention to the holes. Writing in Atlas Obscura, Aïda Amer claimed that Stryker ‘tended to kill images with people smiling’, preferring pictures that were unambiguous in their demonstration of hard times and need. In The Atlantic, Alan Taylor chose images for their strangeness: holes that appear as a baseball cracking off a bat, a UFO in the sky, and an uncanny, empty mask.

Although the negatives had been held by the US Library of Congress since the mid-1940s and made widely accessible by digitisation in the 1990s and early 2000s, such articles emphasised the holes as visible evidence of Stryker’s ‘ruthless’ editorial practice. The holes were becoming visible. Nothing was becoming something. Elsewhere, forces that were mute for decades were also making themselves heard. In the United Kingdom, the historic Brexit vote of June 2016 led to the British prime minister David Cameron’s resignation. Months later, Democrats in the US watched in shock as the country voted to elect Donald Trump as president. Suspicion and resentment reigned. Rediscovery of the ‘killed’ negatives paralleled these political events. Holes were rent in society and these examples of 1930s US government propaganda seemed to confirm the hidden forces at work in everything.

The filmmaker and literary theorist Trinh T Minh-ha finds something politically powerful in holes. In her essay ‘The Image and the Void’ (2016), she recounts a story told by China’s longest-held woman political prisoner, Ngawang Sangdrol, formerly a Tibetan monastic who was sentenced to 23 years’ imprisonment. Sangdrol recalled that Chinese guards showed their Tibetan prisoners newspaper articles that revealed the West’s support for the Dalai Lama and Tibet. The guards took these articles as evidence of Western brainwashing, but the prisoners read them another way. The Tibetans were happy to see their country mentioned favourably in the press. Eventually, the guards understood that their tactic was not working, and they took to cutting out any positive notices about Tibet from the newspapers. Minh-ha relays:

However disconcerting this might have been, it did not deter the Tibetan prisoners from rejoicing upon seeing those glaring holes, for they knew each one represented something good someone was saying about Tibet. A lack thus loses its negative connotation to become an affirmation, and an absence is received as a much-anticipated presence. Fullness and emptiness yield similar results in their representative functions; whether granted for viewing or censored from view, the articles had the same effect on the prisoners.

Museums and libraries preserve other kinds of holes, too. There are many thousands of artists and authors whose work has not been collected or preserved by official archives. Maybe it was deemed unimportant, tangential or in conflict with history’s dominant narrative. There are millions of people whose words never made it into print; there are millions upon millions of thoughts that never made it into words. These absences are also holes in the archive. Contemporary authors have started paying attention to them.

Her method doesn’t fill in all the holes. She uses them to gain purchase, to crack the veneer of historical fact

Toni Morrison reflected on holes in the archive in her essay ‘The Site of Memory’, written while she was at work on the novel Beloved (1987). She explained that, although there exist more than 100 books written by formerly enslaved people in the US, none of these included the interior lives of their authors. The so-called ‘slave narratives’, written for a white abolitionist readership, largely spared their readers the most horrific experiences of enslavement, as well as their authors’ feelings about the trauma. Instead, 18th- and 19th-century Black authors gestured at and glossed over scenes of brutality in order to escape criticisms by the white press of sensationalism or impropriety. Morrison digs into these holes in her fiction. She describes it as ‘a kind of literary archaeology’. She continues:

On the basis of some information and a little bit of guesswork you journey to a site to see what remains were left behind and to reconstruct the world that these remains imply. What makes it fiction is the nature of the imaginative act: my reliance on the image – on the remains – in addition to recollection, to yield up a kind of a truth.

In her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019), Saidiya Hartman gives voice to Black women and girls of the early 20th century whose lives are represented in official archives only as problems to be dealt with. These women imagined and enacted modern ways of living and loving that would be celebrated only when they were adopted later by white women called flappers. Hartman sees these earlier Black women as pioneers of liberation. Their ‘beautiful experiments’ were attempts ‘to make living an art’, despite being pathologised by white institutions as deviant or ‘wayward’.

Hartman had to work actively against the holes in the archive to tell these stories. The documents that name Hartman’s heroines include trial transcripts, reports by vice investigators, social workers and parole officers, sociological surveys, and prison case files: nothing that records the women’s own voices, their hopes or satisfactions. Hartman describes

read[ing] these documents against the grain, disturbing and breaking open the stories they told in order to narrate my own. It required me to speculate, listen intently, read between the lines, attend to the disorder and mess of the archive, and to honour silence.

She gives voice to a speculative past by drawing heavily on details found in the archives, but she focuses on the emotion and agency of the women who were subjects of the archive, rather than its primary authors. Crucially, Hartman’s method doesn’t fill in all the holes. She uses them to gain purchase, to crack the veneer of historical fact. Although she adds more voices to the archive, these few stories are also reminders of all the other stories not yet told.

Holes in the archive are so omnipresent as to be like the water the surrounds a fish, leaving the fish unaware of what water is. In his Kenyon commencement address ‘This Is Water’ (2005), David Foster Wallace unpacked the parable: ‘The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.’

Visible holes in the archives – a hole-punched photograph, a document with rusty pin holes – ought to remind researchers of the many holes that are so vast as to be nearly invisible. When we attend to them like Morrison or Hartman or Pope.L, these holes may reveal all the Universe, what it feels like to live in water. Through these holes flows the air we breathe. Holes in the archive are beacons that invite a search for what – and who – made today possible.

O what point is so marvellous.