How is it that we live in an era of apparently unprecedented choice and yet almost every film and TV series, as well as a good many plays and novels, have exactly the same plot? We meet the protagonist in their ordinary world, plodding along, not living their best life. And then an inciting incident changes everything, making it impossible for the protagonist to carry on as normal. They are pulled into a new quest. On the way, they meet someone who shows them a completely different way of being. They ask themselves: have I been living a lie?

This is the mid-point, the point of no return. Life can never be the same. But there’s a double wobble since the protagonist’s quest is opposed by a powerful antagonist who frustrates the hero at every turn. At their lowest point, the protagonist realises their old mode of being is redundant, but the new one is too daunting. The story is resolved either in the protagonist’s favour or against them: they triumph or else fail tragically. The important thing is that their life philosophy has been turned upside down. When they return home, everything is the same, but everything is also completely transformed.

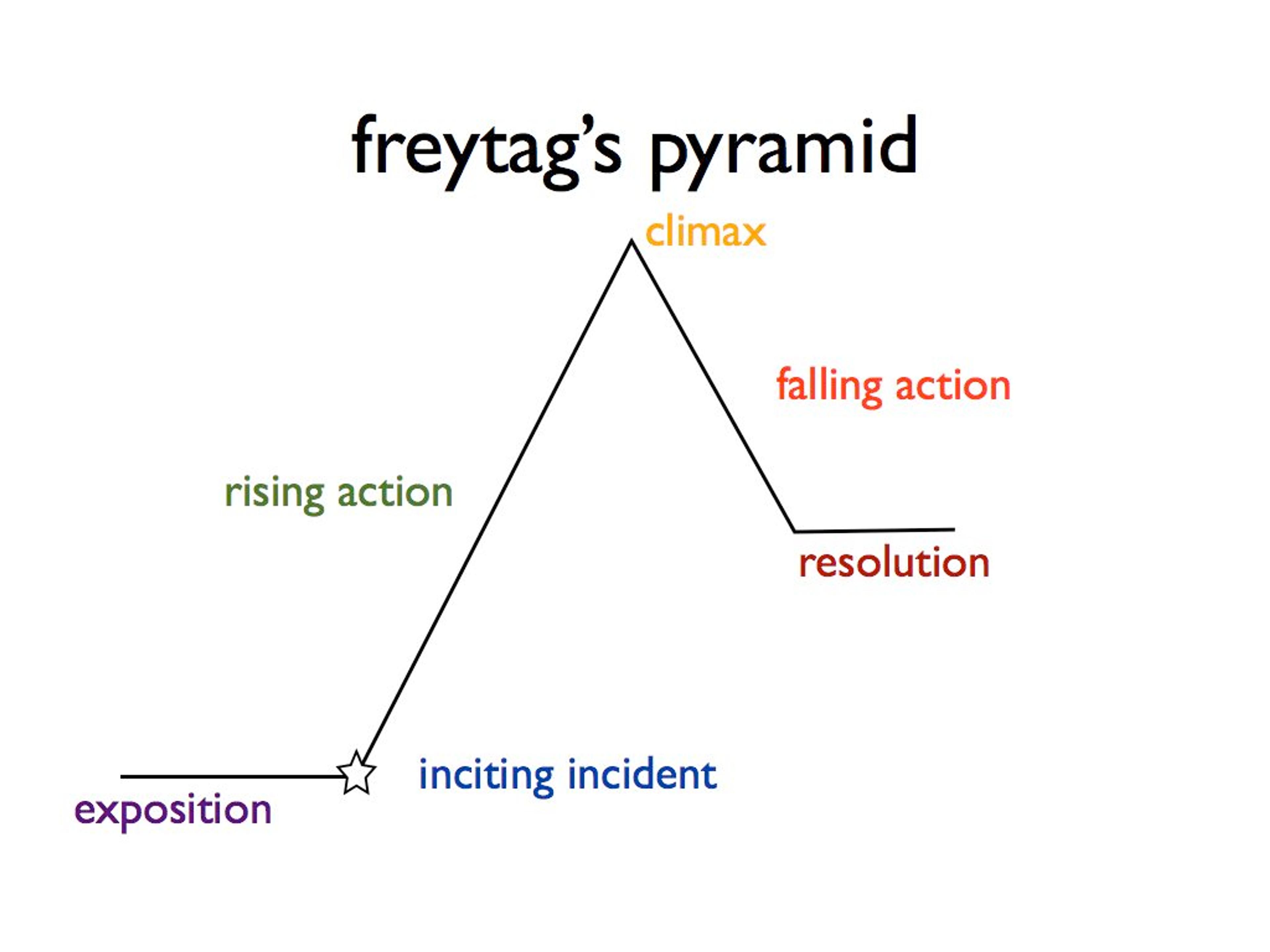

The formula is particularly repetitive in cinema. As it happens, aspiring screenwriters in 21st-century Hollywood are following a rubric set out in the 4th century BCE. In his Poetics, Aristotle defines a well-constructed plot as having three main acts, and names other essential elements such as the ‘reversal of the Situation’, which is ‘a change by which the action veers round to its opposite’ – eg, the moment in The Sixth Sense (1999) when the therapist realises he is dead – and ‘recognition’, which he defines as a ‘change from ignorance to knowledge’ (Oedipus’ recognition is a big one). Aristotle’s schema was developed by later thinkers from Terence and Seneca to the 19th-century German novelist and playwright Gustav Freytag, who distilled stories into his pyramid diagram of exposition, rising action, climax and resolution. A philosophical parallel might arguably be found in Hegel’s dialectic, from thesis to antithesis and finally to synthesis. As the US historian Hayden White observed, even historians tend to shape their accounts of the past using narrative tropes.

If screenwriters continue to propagate the idea that three (or five) acts are the building blocks of every plot, it is because they are eager to find a replicable formula for box-office success. There is now a profitable story-structure industry of books, online lectures, podcasts and courses, with its own gurus, notably Robert McKee and Syd Field. Also Christopher Vogler, who worked as a script analyst at Disney and condensed the US writer Joseph Campbell’s concept of ‘the hero’s journey’ into a popular seven-page memo that then became a book, The Writer’s Journey (1992).

We may be entirely familiar with the corporate clichés of Hollywood, but I don’t think the underpinnings of traditional story structure are necessarily obvious. One of my favourite films, David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive (2001), conforms pretty closely to formulaic structure, even if it is complicated by dream sequences: the inciting incident of the car crash; Betty’s quest to help Rita rediscover her true identity. I believe that one reason we don’t object, don’t groan with boredom, is that the scaffolding is – crucially – hidden. Every film opens with a fresh premise. The inciting incident always feels surprising, to the protagonist and to us alike: it’s a wild card that comes out of nowhere. It is this discreet veiling, in fact, that enables the formula to continue to thrive alongside the evident narrative variety we encounter every time we enter an independent bookshop: from W G Sebald’s collection The Emigrants (1992) to Nicholson Baker’s novel The Mezzanine (1988) to Samantha Harvey’s Booker-winning Orbital (2023). Hollywood’s storymakers may have grown more sophisticated about the method of delivery, but they are still providing the same drug: the shake-up that leads to enlightenment.

It is an enterprise in which convention is disguised as variety, while constraint is disguised as freedom – and this, surely, is the essence of Western consumer capitalism. The American dream could take you anywhere, but still you end up in a cookie-cutter house in the suburbs. Your high street is full of alluring cafés, but most are chains and their products taste the same. We step into the dark space of the cinema hoping to be taken somewhere new, but the journey follows submerged tracks like a theme park ride, and the only available destination is back home. The ‘reset’ at the end of every film feels particularly conformist: it’s as if we’re being invited to experience the fantasy of infinite possibility and radical change, only for the status quo to be reasserted. In fact, the fantasy reinforces the conformity by acting as a kind of safety valve.

As well as finding the concealment perturbing, I argue that there are other reasons to question traditional story structure. While it captures something profound about human needs and wants, it can be subtly conservative and its dominance is symptomatic of a worrying turn against analysis and critique.

In the grand genealogy of story structure exposition, Campbell’s ‘hero’s journey’ was influenced by Carl Jung’s ‘collective unconscious’: the idea that there are basic character archetypes that recur in our dreams and in the myths common to all cultures. Campbell called the hero’s journey the ‘monomyth’, a term he borrowed from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) – a novel that exemplified it for Campbell and which, tellingly, is also considered to be a poster child for experimental fiction. In fact, there is an important – if subtle – distinction to be made here. There is the Hollywood formula, engineered to provide opioid reassurance in the form of redemption and the simultaneous restoration of normality: the hero always achieves self-optimisation within the acceptable confines of bourgeois respectability (which the comedy show Seinfeld rejected with its insistence on ‘no hugging, no learning’). And then there’s the more deep-seated monomyth, a universal blueprint that rather accurately captures the human condition, in which protagonists are put through arduous trials not so that they get what they want but what they counterintuitively need. And sometimes – in tragedy – they don’t get that at all.

Though the Hollywood template might feel imaginatively and politically impoverished, it is also highly resonant. The TV producer and script editor John Yorke is the author of Into the Woods: How Stories Work and Why We Tell Them (2014). He is the closest thing we have to a screenwriting guru in the UK. ‘Hollywood tends to commodify and formalise,’ Yorke told me, but ultimately, ‘they’re commodifying something innate … There are different styles in different cultures, but fundamentally the underlying ingredients are always the same.’ Yorke offers the example of E M Forster: although story structure in novels tends to be looser and sometimes more experimental than that of films, ‘it’s so striking how something really significant always happens bang in the middle’ of a Forster novel – the midpoint Marabar Caves scene in A Passage to India (1924), for example, that overwhelms the young Adela Quested. Yet, as Yorke points out, ‘Forster didn’t read a book on story structure.’ Indeed, the cave literalises that moment of darkness, where Campbell’s model hero believes that all is lost.

Whether the monomyth is hard-wired or naturalised through repetition, Yorke believes it has universal appeal. Consuming it enables us to safely confront our worst fears and vicariously act out our strongest desires. Most importantly, it offers a pathway for what often seems to be the hardest and most longed-for task of all: how to change.

The vast majority of stories we encounter are versions of the monomyth

The US writer and director Craig Mazin observes that the inciting incident that the ‘writer god’ inflicts on the protagonist is their worst fear. It is the very thing they least want to happen, and because of this it has the potential to overhaul their erroneous mindset. The protagonist fights this ‘call to adventure’ tooth and nail because following it would mean letting go of their foundational commitments. Often, the change we need to make is to discover and integrate a vital, suppressed side of our personality – what Jung called our Shadow. The inciting incident represents the protagonist’s Shadow bursting into their world – it is their lack or flaw, embodied – which is why it is so hard to face. Who has not felt panic at the sudden disruption of their best-laid plans, only to find that the disruption produces unexpected rewards? A snowstorm that prevents my children from going to school (and me from obsessing away at my laptop) can become a magical sledging day in the park.

The COVID-19 lockdown was effectively an inciting incident on a global scale, offering us glimpses of how to live more meaningfully: building stronger ties with local communities; leaving urban areas for the countryside; discovering a greater sense of wellbeing through working at home (though, five years on, we appear to have returned to business as usual without learning those lessons – unlike the protagonists in films). Equally alluring is the idea of having a calling, an all-encompassing mission that sweeps away everyday mundanity, to say nothing of the appeal of absconding from a stultifying job or a stifling domestic life. I even wonder, writing this essay, if the lesson I need to learn is to let go of my qualms and enjoy being swept up into story, like Dorothy and her tornado.

The vast majority of stories we encounter are versions of the monomyth – from King Lear to Jane Austen’s Emma (1816). But to what extent is even that a normative Western construct promoting a narrow range of possible life-arcs – with the attendant Hollywood industry replicating it over and over, like an oppressive storytelling machine? And, to look even further outside the frame, is there something inherently reactionary about narrative itself?

Mazin’s reference to the ‘writer god’ is illuminating: it’s a top-down format. Oedipus’ fate is decided by the gods, the oracle at Delphi, and Sophocles: he tries to act freely, but his actions are predetermined. In our postmodern world, this predicament is turbo-charged. The Truman Show (1998) and The Matrix (1999) remain pertinent because we often feel ourselves to be living in a dystopian version of Prospero’s island – mere puppets in someone else’s plot. We process through the sausage factory of the National Curriculum into jobs that are standardised by tick-box bureaucracies. We are pawns preyed on by advertisers, and we’re trapped within the rubrics of social media. Every few years, we are given the chance to choose between near-identical parties, while our lifestyle choices are imperceptibly shaped by paternalistic nudge policies. In our scant downtime, we succumb to the consoling grooves of alcohol, gaming or Netflix.

You don’t have to be a conspiracy theorist to suspect that the lack of agency we feel in a world dominated by autocrats and digital capitalism is connected to the rise of story as a form. In his book Public Opinion (1922), the US political commentator Walter Lippmann called on Hollywood, the dream factory, to control an irrational public by appealing to their unconscious: the infamous ‘manufacture of consent’. And as the French scholar Christian Salmon notes in Storytelling: Bewitching the Modern Mind (2010), narrative has spread throughout contemporary culture and society, from news features to political speeches; museum curation to TV documentaries. Even in radio, where I work, and despite the best efforts of many of my colleagues to defend ideas-led programmes, formulaic narrative podcasts – particularly about history and true crime – are increasingly prevalent. The repetitive elements of storytelling are only too obvious here: the use of suspenseful music and the historic present tense, the anchoring in relatable characters, the cliff-hangers. Being told a story is to be infantilised, somewhat: to suspend one’s critical faculties. In contrast to polemic, stories are covertly persuasive. Even if their message is good for us, the sugaring of the pill represents a lowering of intellectual expectations.

There may be an internal transformation, but the structural conditions remain the same

Stories, as Vogler told me, function as ‘a kind of wish fulfilment’, meeting the human craving for ‘order and a purpose’. Regarding life as simply chaotic or meaningless is, he says, a ‘dangerous mental condition, … a horrible place to be’. Real life, of course, doesn’t have a shape as such. As Aristotle put it in his Poetics: ‘infinitely various are the incidents in one man’s life which cannot be reduced to unity’. Things don’t happen for a reason. And we fail to learn lessons. The UK novelist and critic Rosalind Brown points to the pitfalls of imposing meaning on contingent life events: ‘when something happens to you, you just make it part of your story’. It can be a way of avoiding being proactive or taking responsibility. That is one reason why we are rightly ‘suspicious of story’, Brown told me, even while being ‘incredibly attached to it’.

If Brown is right, there is a danger that the ‘hero’s journey’ monomyth enables us not to change but to experience the fantasy of doing so. Sometimes ‘it’s easier to read about another character changing and feeling attracted to that than actually doing whatever work it would require to change yourself,’ she says. As Yorke reminded me, however, the power of stories to change us is illustrated by the money that the Donald Trump campaign spent on narrative social media spots, Lippmann-style – a gamble that, for better or worse, largely paid off. ‘The story wouldn’t be any good if you came back to your normal life completely unchanged, and having learned nothing, or having had no new observation,’ Vogler told me. ‘I think that we are always searching for upgrades, improvements in our behaviour, in our performance, in our relationships with other people.’ Films, he says, offer the opportunity for ‘slight improvement’.

There is also the question of whether the kind of change the monomyth advocates is always in our best interests. The politics of most mass-market screen fictions – from the fake anticolonialism of Avatar (2009) to the fake feminism of Barbie (2023) – are covertly conservative. The White Lotus (season one, 2021) came close to questioning the sustainability of long-term relationships, before ducking the issue with the sentimental reunion of husband and wife. The lesson is very often to be happy with your lot and to celebrate the comforts of the nuclear family, small-town existence and, often, capitalism. I’m thinking of It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) and Groundhog Day (1993) – even though I love Groundhog Day, and its repetition concept manages, simultaneously, to portray and critique being stuck in a rut. There may be an internal transformation, but the structural conditions remain the same.

So, what happens when we truly break with convention?

Naqqash Khalid is a UK writer-director best known for his debut In Camera (2023), a surreal and disorientating portrait of an aspiring British-Asian actor navigating unsuccessful auditions. I asked him about my experience of noticing the same plot points time and again. ‘I can’t stand that. It really drives me crazy,’ he told me. ‘I am critical of the three-act structure, because I think it’s a very Western, male, colonial conception.’ The protagonist of In Camera is very much not a self-determining hero: he is framed and constructed by the encounters he has with other characters, who are often casually racist. ‘I wanted to have a passive man at the centre of the narrative who was not pushing the story forward,’ Khalid told me. He regards ‘one man going on a journey’ as not only hackneyed but ‘patriarchal’.

Similarly, the Australian critic Jane Alison questions the ‘masculo-sexual’ three-act structure with its wave-like arc of tension and release. ‘Why should an art form as innovative as fiction have a single archetype at all?’ she asks in ‘Beyond the Narrative Arc’ (2019). Stories can follow different patterns, she observes, many of which recur in nature: as well as the wave, there are fractals, meanders and networks – Italo Calvino described his novel Invisible Cities (1972) as ‘a network in which one can follow multiple routes and draw multiple, ramified conclusions.’

In her essay ‘The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction’ (1986), Ursula K Le Guin challenged the hero’s journey – ‘the story the mammoth hunters told about bashing, thrusting, raping, killing’ – as not only narrowly masculine but also threatening humanity’s survival. Le Guin makes the case for an alternative story form to the hero’s spear or club: that of a container. Serious fiction, Le Guin wrote, is ‘a way of trying to describe what is in fact going on, what people actually do and feel, how people relate to everything else in this vast sack, this belly of the universe, this womb of things to be and tomb of things that were’.

Khalid also believes that contemporary art should reflect reality through its very form, and not just dangle wish fulfilment. ‘We live in such fractured times where the news cycle is nothing like before, where our attention spans are short,’ he said. Films must ‘formally adapt to the time that we’re in … I think the role of art is to structurally represent the world back to us.’ In her novel The Long Form (2023), Kate Briggs records the minute-by-minute tedium of being at home with a baby: the recording of mundane details functions as a critique of the conditions of modern motherhood. Rosalind Brown’s debut Practice (2024) is another novel that depicts what it is actually like to live in the world, right now. Annabel is an English literature undergraduate trying and failing to complete an essay about Shakespeare’s sonnets, through the minutiae of a single day. She is interrupted by erotic thoughts. She goes for a walk. She eats lunch. ‘The food is wet and crunchy, and tastes of all the cutting-up she just did to it,’ Brown writes: a sentence that stops the reader in their tracks. ‘Texture is the thing that interests me,’ Brown told me. Annabel ends the day much as she started it, the essay incomplete (although Brown does not reject story structure altogether: Annabel relaxing her grip on her timetable is an enlightenment of sorts).

Late capitalism, it would seem, respects neither narrative nor planetary boundaries

Early 20th-century literary modernism rejected the smooth illusions of 19th-century fiction, grappling instead with the dislocations of postwar modernity. Likewise, these attempts, in Le Guin’s words, ‘to describe what is in fact going on, what people actually do and feel’ are aesthetically and politically bracing. They defamiliarise what is naturalised, making the world strange so we can see it, challenge it, and potentially change it. Traditional story structure may resonate deeply, but it does not give us that jolt. Paradoxically, the monomyth dramatises change, but also embodies continuity.

‘Stories allow us to progress, and they allow us to stay the same,’ Yorke said. ‘That’s probably quite a healthy balance … We tell stories to define ourselves, our families, our nations.’ The monomyth was modelled on stories told by traditional societies governed by cyclical time and generational renewal: the hero’s journey is a rite of passage. But now that real-world Bond villains like Elon Musk are threatening geopolitical stability and ecological survival, that final-act reset is surely coming under strain.

Ironically, the monomyth is now being stretched out of shape by commercial forces, too. Franchises, sequels and box-set formats are extending stories in multiple directions to eke out ever more revenue, bringing to mind Musk’s intergalactic ambitions, which imply there’s a franchise option for human life: late capitalism, it would seem, respects neither narrative nor planetary boundaries. ‘It’s outrageous, really,’ Yorke says of endless sequels. ‘If you think of it in basic terms, a story is a question and answer, dramatised. And when the question is answered, there is nowhere else to go.’ Not surprisingly, Hollywood is working hard to combine narrative boundlessness with satisfying, self-contained stories: the Marvel ‘Multiverse’ is a kind of vast conglomerate of autonomous (super)heroes’ journeys.

In contrast to the spectacle of an individual saving the world, we once had idealism and the sense of a common goal: it was called ideology. But grand narratives are a relic of the past century. Khalid links the relative absence of creative experimentation with a narrowing of our ideological horizons. ‘Our collective imaginations … are being stifled,’ he told me. Like Le Guin, he believes that we must ‘fundamentally think about how we rebuild structures’, because those we are living under ‘are literally killing us … whether that be patriarchy or racism or the climate catastrophe.’ Ambitious art can ‘shape what we think it is possible for us to do.’

Vogler and Yorke, while supportive of experimental fictions, note that they are of course harder to finance. And although it may be counterproductive to reassure people that everything is fine when the planet is burning, Yorke insists on being realistic about audience choices in a free market. ‘Stories have to make you alarmed,’ he told me, ‘but they also have to offer you hope … You’ve got to have a model of what’s worth living for.’

Even art-house films that self-consciously depart from the three-act structure nonetheless define themselves against it. Charlie Kaufman’s brilliantly metafictional Adaptation (2002) dramatises a deconstruction of the formula (the protagonist, a struggling screenwriter, even attends a seminar by Robert McKee); but still he ends up (albeit knowingly) following it. Abandoning the structure altogether, it seems, is neither desirable nor possible. Even so, whether we regard it as a palace or a prison, we need now more than ever to understand how it is built.