In the late 1620s, nearly two centuries before Mary Shelley helped establish the genre of science fiction with her landmark novel Frankenstein (1818), an English bishop named Francis Godwin wrote a speculative tale about beings living on another world. Titled The Man in the Moone (1638), Godwin’s story is significant not only as a work of proto-sci-fi, but also because it contains perhaps the earliest mention of an extraterrestrial language. ‘The difficulty of that language is not to be conceived,’ the narrator complains when initially sojourning in the utopian society of the Lunars, ‘because it consists not so much of words and letters, as of tunes and uncouth sounds, that no letters can express.’ Rather than imagining a language like those he was familiar with, Godwin dreamed of something deeply perplexing: a musical tongue sung-spoken by Moon-dwellers. ‘This is a great mystery,’ the narrator reflects, and worth ‘searching after’.

Frontispiece from Godwin’s The Man in the Moone (1638). Courtesy the Houghton Library, Harvard University

And then, in the 19th century, the boundaries between storytelling and science began to blur. Originally conceived in fiction, the idea of extraterrestrial language and the quest to understand it were adopted by scientists. The first serious proposal for communicating with aliens came in 1820, as a wave of industrialisation swept through Europe. Generally attributed to the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss, the plan involved ‘drawing’ a colossal mathematical diagram on the surface of Earth: a Pythagorean theorem illustrated through pine trees and wheat fields stretching hundreds of kilometres. Gauss hoped the diagram would be so large that it could be seen by inhabitants of the Moon or Mars.

In the centuries since, science and science fiction have interrogated the notion of extraterrestrial language in tandem, spawning a tangled web of theories and stories, theories about stories, stories about theories, and theories about theories in stories (such as this essay), while prompting many further attempts to communicate with alien beings. This historical interplay has recently culminated in a new wave of interest in the study of alien language, a field known as xenolinguistics (and sometimes exolinguistics or astrolinguistics). But rather than aligning with sci-fi, this aspiring science marks a break with its past. In the process of gaining recognition, xenolinguistics appears to be moving away from the tradition that enabled it.

The problem is that the extraterrestrials that xenolinguists claim to seek are often beings imagined to have technologies, minds or languages similar to ours. They are projections of ourselves. This anthropomorphism risks blinding us to truly alien communicators, who are radically unlike us. If there are linguistic beings on planets such as TOI-700 d or Kepler-186f, or elsewhere in our galaxy, their modes of communication may be utterly incomprehensible to us. How, then, can xenolinguistics face its deficit of imagination?

Artist’s depiction of Kepler-186f (foreground) as a rocky, Earth-like planet in the habitable zone. Courtesy Wikipedia

Perhaps by re-engaging its speculative origins. Through the mode of thought characteristic of science fiction, the science of alien language might yet learn to open itself to every conceivable degree of otherness, even the possibility of beings that share nothing with us but the cosmos.

The modern project to communicate with extraterrestrials begins with Gauss’s colossal diagram and the various schemes that his idea inspired in the latter half of the 19th century. Such proposals to signal aliens included: igniting kerosene poured into enormous ditches shaped like geometric figures, burning messages into the deserts of Mars and Venus with a giant mirror that focused sunlight, and flashing Morse code with electric lights. By the end of the century, European excitement about the possibility of communing with our solar-system neighbours had reached fever pitch. In 1900, the Prix Pierre Guzman, a prize of 100,000 francs administered by the Académie des sciences in Paris, was offered to whoever could first ping the inhabitants of another celestial body (except for Mars, which was deemed too easy).

Around this time, the radio wave became a more feasible medium for off-world communication. In 1901, after earlier experiments, the inventor Guglielmo Marconi transmitted a signal (the Morse code for the letter ‘S’) across the Atlantic Ocean. That same year, his rival inventor Nikola Tesla raved about receiving a radio signal from Mars – a claim dismissed by many of his fellow scientists, despite excitement in the press. However, as telecommunications technology progressed in the 20th century, governments and institutions began to take the sending and receiving of extraterrestrial messages more seriously, and even provided funding for such projects.

Inside an antenna mirror of the Yevpatoria RT-70 radio telescope. Courtesy Wikipedia

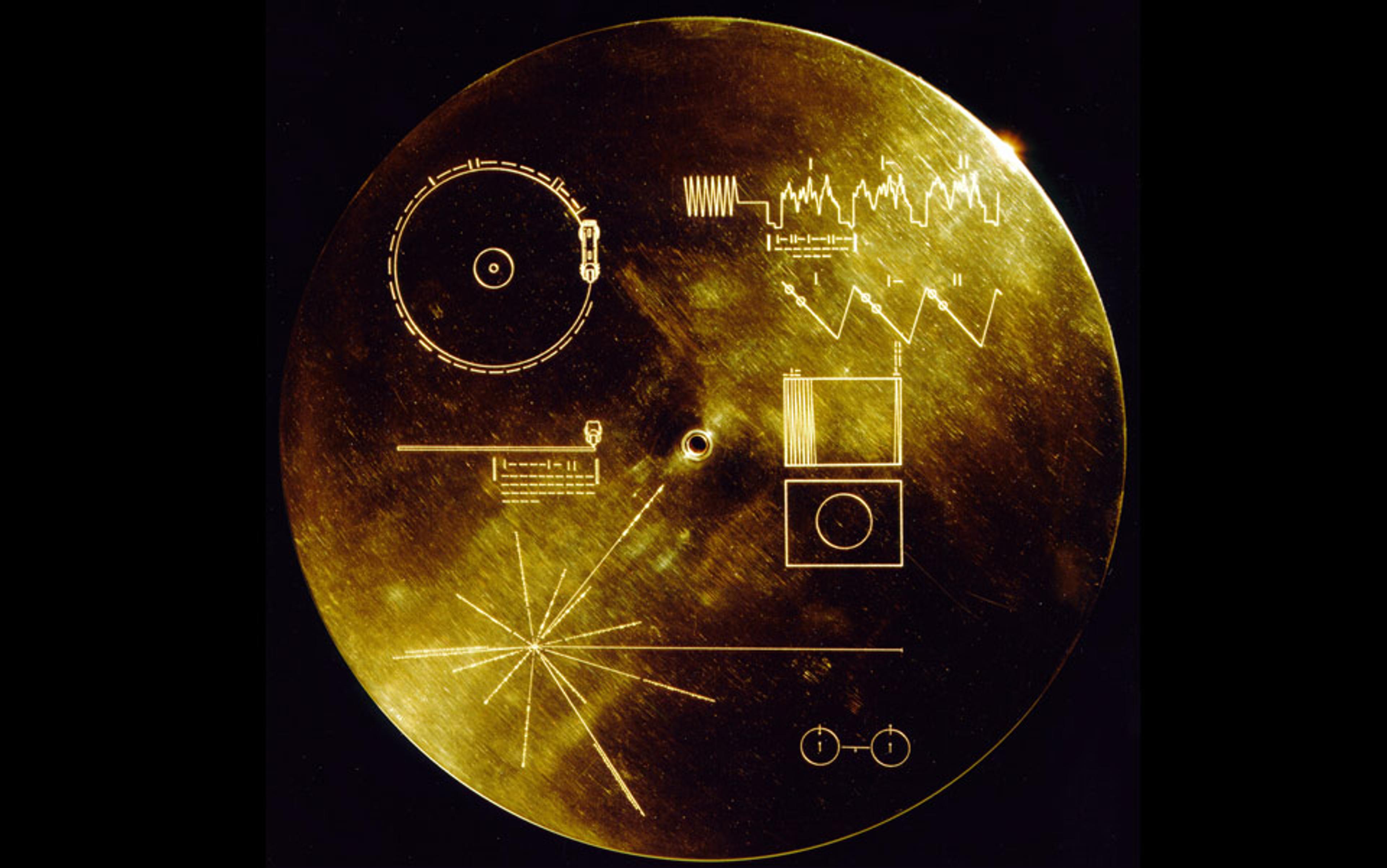

In 1962, the Yevpatoria radio telescope in Crimea aimed a high-frequency transmission at Venus. These Morse-code messages consisted of just three Russian words: ‘Lenin’, ‘CCCP’ (the Cyrillic for USSR), and ‘mir’ (meaning either ‘world’ or ‘peace’). In 1974, American researchers aimed a message from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico at the M13 cluster of stars, some 25,000 light-years away. The transmission was overseen by the astronomers Carl Sagan and Frank Drake, who had previously designed the first interstellar physical messages: a pair of identical metal plaques engraved with symbols and diagrams, which were placed aboard the spacecraft Pioneers 10 and 11 launched in 1972 and ’73. Since then, multiple attempts have been made to contact aliens.

Three cultural shifts help to explain why xenolinguistics is gaining legitimacy

In recent decades, centuries after Godwin conceived of linguistic aliens and Gauss made moves to communicate with them, xenolinguistics has finally begun to gain its footing as a legitimate scientific discipline. Rather than being pushed to the fringes for its historical association with science fiction, it is being accepted by mainstream institutions, as demonstrated by the release of an unprecedented number of books on the topic by esteemed academic publishers.

In 2012, Springer put out Astrolinguistics, in which the computer scientist Alexander Ollongren updates the earlier Lingua Cosmica (or Lincos) system for designing interstellar messages using formal logic. By the end of the decade, MIT Press had published Extraterrestrial Languages (2019), a nonfiction survey of the field by the science writer Daniel Oberhaus. In 2023, Routledge followed with an anthology of research papers on the topic, Xenolinguistics: Towards a Science of Extraterrestrial Language, featuring a paper co-written by Noam Chomsky, the father of modern linguistics. This was followed by the philosopher Matti Eklund’s Alien Structure: Language and Reality (2024), a monograph from Oxford University Press that emerged out of a xenolinguistics research group at Uppsala University in Sweden.

Three cultural shifts help to explain why xenolinguistics is gaining legitimacy. The first is the release by the US government of videos showing unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) and the coverage of these by mainstream news outlets in 2020. The second is the rapid progress of astronomy in the 21st century, with hundreds of new exoplanets discovered each year and increasingly sophisticated methods for modelling their composition. If any one UAP were proven to be extraterrestrial in origin, or an exoplanet were to display signatures of life or technology, we would have potential evidence of aliens with whom we might hope to communicate. The third cultural shift is the equally rapid progress in machine learning. This raises the possibility of one day conversing with a sentient artificial intelligence (itself a kind of theoretical ‘alien’) and has already sparked renewed efforts to crack animal communication, especially that of cetaceans, birds and primates. Successful communication with a nonhuman terrestrial interlocutor, whether artificial or biological, would add prima facie plausibility to the existence of linguistic minds elsewhere in the galaxy.

Such developments have synergised during the past decade to make xenolinguistics appear more viable and attractive. But critical difficulties remain: not only do we lack evidence for linguistic aliens, but there is little reason to anticipate that we will remedy this any time soon.

The most credible attempts to find proof of linguistic aliens have been associated with SETI, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. The SETI movement has been active since 1960, wielding arrays of radio and optical telescopes to scan the skies for thousands upon thousands of hours in a wide range of frequencies, and utilising a significant amount of computing power to parse those readings. It has yet to detect a single beacon (aside from the fleeting ‘Wow! signal’ of 1977, which failed to meet the fundamental scientific criterion of repeatability). Likewise, our surveys of other planets and asteroids have not discovered even one primitive microbe originating outside Earth. Our evidence for linguistic aliens is nil.

The increasing institutional acceptance of xenolinguistics, therefore, must rest upon the expectation that we will, at some point in the future, receive an extraterrestrial message. However, experts have challenged this expectation since SETI’s outset.

In Civilized Life in the Universe (2006), the science historian George Basalla points out that the project of listening for alien transmissions implicitly assumes that there are an adequate number of nearby extraterrestrials using radio technology similar to ours. The development of radio telescopes requires a technological civilisation with science much like ours, which likely requires beings whose cognitive and cultural makeup closely mirrors our own. That is, SETI implies a galaxy full of anthropomorphic (if not necessarily humanoid) aliens. The galaxy would need to be ‘full’ because, as Drake tried to quantify with his eponymous equation in 1961, the density of aliens in our neighbourhood of the Milky Way would have to be sufficiently high for their signals to have a reasonable chance of reaching us.

Decades of failure have not budged SETI’s ongoing commitment to the search for anthropomorphic extraterrestrials

Evolutionary biologists, such as Ernst Mayr, have challenged the idea of a universe full of anthropomorphic aliens on the grounds that evolution is based upon too many haphazard occurrences for doppelgänger species to emerge around other stars. For example, if an asteroid hadn’t wiped out the dinosaurs, mammals would not have become dominant, and Homo sapiens would never have evolved. Even on planets identical to Earth in all relevant respects, which must be vanishingly rare, the exact concatenation of pressures across scales of geological time that give rise to an organism’s specific traits, including the capacity for technology and language in our case, cannot reasonably be expected to be repeated.

Every day that we fail to detect alien signals is further support for such criticisms and gives more reason to doubt that off-world signals are on their way to Earth. And yet, for SETI, decades of failure have not budged its ongoing commitment to the search for anthropomorphic extraterrestrials.

There seems to be an element of metaphysical superstition to this perseverance. Basalla has noted the continuity of ancient religious cosmologies of superior beings from the heavens, such as angels or saints, with the thinking of SETI evangelists. Consider Drake, who wrote publicly about his belief that aliens were immortals destined to share the secret of eternal life with us, or Sagan, who unflaggingly promoted his faith in hyper-advanced but benevolent civilisations bound to save humankind from follies such as nuclear war.

An effort is currently afoot to rebrand SETI as the search for technosignatures – meaning evidence of technology (and, by extension, the life form that created it). Since the technologies sought are those used now or predicted to be used by humans, this emerging subfield of astrobiology is likely afflicted with the very same anthropomorphic bias as the old version of SETI. Be that as it may, evidence of extraterrestrial technology is not ipso facto evidence of alien language. Only a verified alien message would count as such evidence. Therefore, message-hunting SETI remains the key to justifying the pursuit of xenolinguistics as a traditional empirical science, and the problems that afflict the former remain problems for the latter.

When it comes to conceiving of communicative extraterrestrials, xenolinguistics appears to be on shaky ground. Science fiction hasn’t fared much better. In the rare cases where authors have taken the problem of alien languages seriously, the potential for genuine insight has usually been hindered by a tendency to anthropomorphise – much like SETI. However, there are a small but growing number of stories that succeed in carrying our mind beyond this bias and on toward visions of ultimate otherness. Could these imaginative interventions help rehabilitate the aspiring science of alien language?

Although The Man in the Moone seems to contain the first mention of extraterrestrial language – in science fiction or anywhere – the first technical description of such a language is likely that found in Across the Zodiac (1880), a novel by the political writer and historian Percy Greg. The ‘Martial language’ he describes is optimised for easy memorisation, with ‘no exceptions or irregularities’ and words built systematically from a small number of roots. This initial effort anticipated the production of imagined languages – what the fantasy author and philologist J R R Tolkien dubbed ‘glossopoeia’ – that would preoccupy many sci-fi authors in the 20th century. These linguistic experiments have taken myriad forms, from the communication innovation that shapes a planetary-scale revolution in Jack Vance’s The Languages of Pao (1958) to the feminist Láadan language featured in Suzette Haden Elgin’s Native Tongue (1984). With the possible exception of Tolkien’s Elvish, the most famous language constructed for fiction (or ‘conlang’) is Klingon, the speech of its eponymous alien race in the Star Trek franchise. The grammar, vocabulary and pronunciation of Klingon are sufficiently well developed for some hardcore fans to have become fluent speakers, while the script has been used to translate such ancient classics as The Epic of Gilgamesh and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War.

However, these meticulous explorations of alien language are the exception. As many commentators have noted, beginning with the literature scholar Walter E Meyers in Aliens and Linguists (1980), science-fiction stories have tended to give the topic of linguistics short shrift, especially in comparison with the attention paid to details of ‘hard’ sciences like physics or engineering. If the problem of alien communication is raised at all, any difficulty or strangeness is often rendered human and familiar. This is achieved through several strategies: the convenient device of telepathy, found frequently in golden-age pulp magazines of the mid-20th century; the easy postulation of a galactic lingua franca such as Galactic Basic (ie, English) in the Star Wars franchise; or by technological fiat, as with machines that easily translate between any language in the cosmos, including the universal translator in Star Trek, the TARDIS in Doctor Who, the Babel fish in Douglas Adams’s The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1979), and droids such as C-3PO in Star Wars.

There is a strand of sci-fi that has succeeded in carrying its speculations toward the pole of incommunicability

Even stories that make more sincere efforts to exclude anthropomorphism from their treatment of alien language can still succumb to it. Klingon is the most sophisticated embodiment of this tendency. Though it has linguistic features uncommon to most languages, including distinct grammatical patterns and complex stacks of suffixes, it is still the language of an imagined humanoid race. Furthermore, it’s a language that is spoken by humans. Klingon’s capacity to be used by us is a strike against its realisation of genuine difference.

These and other examples demonstrate science fiction’s bad habit of projecting human qualities onto alien language, cognition and culture. Thankfully, there is a strand of the genre that has succeeded in carrying its speculations in the opposite direction, toward the mystic and mystifying pole of incommunicability.

In her debut novel Rocannon’s World (1966), Ursula K Le Guin imagines a race of semi-telepathic dwarven aliens called the Fiia who use no proper names for things even within their local landscape. In one passage, the human protagonist Rocannon interrogates his Fiia companion Kyo about this perplexing linguistic quirk:

‘At each village here I ask what are those western mountains called, the range that towers over their lives from birth to death, and they say, “Those are mountains, Olhor.”’

‘So they are,’ said Kyo.

‘But there are other mountains – the lower range to the east, along this same valley! How do you know one range from another, one being from another, without names?’

Clasping his knees, the Fian gazed at the sunset peaks burning high in the west. After a while Rocannon realised that he was not going to answer.

Ultimately, Rocannon’s question is met with silence, gesturing to the barrier of ineffability between the two species. In other stories, this barrier can be broken but only through a profound transformation of the mind, as with the written language of the seven-limbed Heptapods in Ted Chiang’s novella ‘Story of Your Life’ (1998), adapted into the film Arrival (2016). The protagonist, a professional linguist, gradually learns that the Heptapods’ ideogram-like script is not broken into sequential units such as morphemes or words, but written as a holistic semantic gestalt in which the whole and the parts are grasped simultaneously. ‘There was no direction inherent in the way propositions were connected,’ the protagonist realises, ‘no “train of thought” moving along a particular route.’ Learning to read and write like a Heptapod ultimately requires her to upend her temporal perception, experiencing ‘past and future all at once’.

In Solaris, the behaviour of its titular planetary ocean defies all notions of sentience, understanding and even life

However, the transformation of an individual mind is not always enough. Sometimes, a more drastic reshaping of both the self and the other is demanded. In China Miéville’s novel Embassytown (2011), the Ariekei (known as Hosts) speak a language in which paired expressions must be uttered simultaneously by two voices operated by a single mind. This requires human visitors to genetically engineer twin interpreters ‘with unified minds’.

Other stories go yet further, pushing us to the very boundary of communicability – and beyond. At the farthest extreme of alterity is Stanisław Lem’s novel Solaris (1961), where the complex behaviour of its titular planetary ocean defies all notions of sentience, understanding and even life:

Its undulating surface was capable of giving rise to the most diverse formations that bore no resemblance to anything terrestrial, on top of which the purpose – adaptive, cognitive, or whatever – of those often violent eruptions of plasmic ‘creativity’ remained a total mystery.

In Lem’s vision, decades of vigorous research in the pandisciplinary field of ‘Solaristics’ have failed to identify any comprehensible human meaning in the godlike sea of plasma. The sea, however, has no trouble simulating our consciousness and sense of meaning, as evidenced by the recreation of the protagonist’s long-dead lover from his memory. But the protagonist struggles to fathom the intention, if any, of this replication. Even when the ocean anthropomorphises itself through humanlike forms, he cannot make sense of it within his narrow anthropomorphic framework.

These narratives illustrate how science fiction that explores the otherness of extraterrestrials thoroughly and penetratingly can propel us beyond the comfort zone of humanlike aliens – a space within which SETI and xenolinguistic theory remain trapped.

If we did encounter an apparent message from beyond Earth, how difficult would it be to understand? Where between the poles of communicability – from the naive anthropomorphism of Star Wars’s Galactic Basic to the utter inscrutability of Lem’s plasma ocean – would such a signal likely fall? This is the central problem for xenolinguistics.

Several theoretical arguments cherished by xenolinguistics proponents assert that we should expect extraterrestrials to occupy the anthropomorphic side of the spectrum. The most influential of these comes from the AI pioneer Marvin Minsky’s paper ‘Communication with Alien Intelligence’ (1985). Minsky had previously tested the simplest possible computational algorithms and found that most performed pointless operations. However, under the same constraints, some algorithms did something different: they performed a similar counting operation. By analogy, Minsky asserted that all species in the Universe, given the shared constraints of matter in space and time, would likewise converge on the same simple cognitive solutions. This ubiquitous mental foundation, he concluded, should make communication between humans and extraterrestrials possible, both mathematically and linguistically.

Building on this argument in a paper published in Xenolinguistics: Towards a Science of Extraterrestrial Language, Noam Chomsky and his co-authors Ian Roberts and Jeffrey Watumull speculated that Chomsky’s seminal theory of ‘universal grammar’ may apply to all intelligent beings, not just humans. In recent decades, research on universal grammar has focused on a concept called ‘merge’, which is a simple operation that combines two syntactic objects (such as words or phrases) without altering them. Proponents believe that merge is an innate structure that underlies all known languages. In the paper, the authors suggest that merge could be one of the evolutionary solutions that Minsky thought all organisms would discover. If so, every intelligent being in the Universe would necessarily evolve a language faculty like our own. Universal grammar would then become truly universal, what I think of as ‘cosmic grammar’: a hardwired guarantee of the potential for a dialogue between intelligent beings across space and time.

If only such reasoning held together. The first problem is the assumption that the brain or mind is computational. Today, many psychologists, neuroscientists and philosophers reject the computational metaphor of the mind. If they are correct, the analogy between computation and cognition essential to Minsky’s argument (and the argument for cosmic grammar) breaks apart.

The fallback for xenolinguistics devotees is to insist that math and logic must be understood universally

But even if this outdated cognitivist trope stands, many linguists have challenged the notion that humans possess universal grammar, pointing to alternative theories that explain how language can be acquired without a shared innate faculty. Others have argued that even if cosmic grammar grants every being the same innate computational system for generating syntactic structures, differences in a separate system we require to generate the words and concepts that endow those structures with meaning could still make humans and aliens mutually incomprehensible. Moreover, even if the gulf separating our semantic cognition is traversable, language is always contextual. This throws doubt on the likelihood of decoding messages from aliens without prior knowledge of their bodies, senses, and how these might guide communication in their native habitats.

This argument is bolstered by the philosopher David Ellis’s chapter in Exophilosophy: The Philosophical Implications of Alien Life (2024), titled ‘If An Alien Could Talk, Could We Understand It?’, which is a play on Ludwig Wittgenstein’s provocation: ‘If a lion could talk, we could not understand him.’ In Philosophical Investigations (1953), Wittgenstein put forward the theory that we communicate through a series of language games, such as chatting at a dinner party, telling a joke, or screaming a warning. The meaning of particular expressions can be understood only in the context of the language game within which they are used, while the meaning of a game is determined by the form of life of its players. But since humans and lions do not share a form of life, we would be unable to understand them, even if they somehow uttered our words. Extraterrestrials might have a form of life that diverges in even more radical ways, entailing that their language would elude us. The only exception, Ellis argues, would be if aliens and humans were to establish societies together and cultivate a communal form of life through which we could play shared language games. However, Ellis’s optimistic scenario seems to require aliens whose biological constitution matches ours so closely that they could live as we do – a narrower version of anthropomorphism even than the one entertained by Sagan, who thought that alien interlocutors may not necessarily be carbon based.

The fallback for xenolinguistics devotees here is to insist that, even if natural language is a dead end, math and logic must be understood universally. This view has undergirded the design of most interstellar messages sent to date, and of astrolanguages like Lincos, but is an area, again, where philosophers and mathematicians disagree. The standard justification for such a view relies on expert intuition – specifically the belief that numbers exist, in a Platonic sense, independently of human minds. In other words, these experts assert that mathematics is something humans discovered rather than invented. Yet, if mathematicians are to make bold assertions about the cosmic validity of human mathematics, especially when these claims have implications for empirical science, they should support them with formal proof rather than intuition. And even if extraterrestrials do share our mathematics, the cognitive, syntactic, semantic and contextual difficulties would still make meaningful communication highly unlikely.

This theoretical pessimism has empirical support. We have struggled for decades to decode animal communication, even that of our mammal relatives. Some have concluded that animals lack anything like language, but it is equally possible that our methods are shoddy, or that humans are constitutionally incapable of understanding other species. Even more disheartening is our failure to decipher the scripts of numerous dead languages. Our difficulties divining the thoughts of terrestrial organisms, including members of our own species, ought to chasten our confidence in cracking the enigma of interlocutors who might have emerged on some unknown world.

Alongside the ongoing failure of our quest for alien messages, the above arguments would seem to leave the prospects for a xenolinguistic science highly uncertain. They suggest that there are no linguistic extraterrestrials within range of us and that, even if there were, we would be unable to communicate with them. However, I believe there can still be great value in xenolinguistics – as long as those seeking communication can jettison the presumption that the aliens we find will be like us.

Recent xenolinguistics papers have adopted the opposite approach, attempting to theorise alien language only from existing knowledge of human and animal communication on Earth. However, at minimum, xenolinguistics must implicitly posit an alien interlocutor, which demands an act of imaginative extrapolation. To even conceive of an alien language in the absence of an alien message is to already be engaging in the speculative mode of thought that characterises science fiction.

The necessity of such speculation would persist well beyond first contact. For even if we were to receive a love letter from the cosmos tomorrow, it might take decades, or infinitely longer, to decode. Naturally, there would be ambiguity, igniting protracted debates on the precise interpretation. A response may take just as long for us to formulate. And then, we would wait for information to arrive, perhaps for centuries, while our interlocutor remained shrouded in mystery. During this conversation across light years, extrapolations that overstep our scant data and hard-nosed scientific norms would be irresistible. Even if we were to come face to face with such linguistic aliens (assuming they have faces), their language would likely remain partially incomprehensible, necessitating more imaginative leaps to fill in the gaps. Finally, supposing we succeeded with one language, there would still be a whole multiverse of possible languages demanding a repeat of the same slow process. Xenolinguistics, therefore, is destined to be inextricably bound with science-fiction speculation for ages to come – perhaps for as long as we pursue it.

Xenolinguistics liberated from anthropomorphic bias posits a spectrum of infinite linguistic alterity

Some might take this insinuation of an intimate relationship between xenolinguistics and sci-fi as a denunciation of the former, taking the naive stance that science pursues truth, while fiction merely lies. However, if these uneasy bedfellows can embrace, as they must, the study of xenolinguistics will be an immense boon to humanity, irrespective of whether it will ever produce scientific knowledge in the traditional sense. How so? By serving as an exercise in opening us up to the maximum degree of otherness conceivable.

For xenolinguistics to realise this potential, researchers and storytellers alike must cast off the anthropomorphism that has typically infected both SETI and science fiction. Our tendency to project our characteristics onto the world has been pointed out at least since the 6th century BCE when the philosopher Xenophanes complained that Greek gods acted like humans in stories and myths. As the philosopher David Hume put it in his essay ‘The Natural History of Religion’ (1757): ‘There is an universal tendency amongst mankind to conceive all beings like themselves, and to transfer to every object those qualities.’

We can begin to counteract this tendency by accepting that we have no idea what aliens are like. Since nothing definitive can be said about the alien interlocutor that is axiomatic to the field, it is most reasonable to stipulate instead beings whose difference from us is indeterminate. That is, xenolinguistics liberated from anthropomorphic bias posits a spectrum of infinite linguistic alterity. Once the fetters of anthropomorphism are loosened, the essence of xenolinguistics is revealed to be a state of readiness to receive or initiate communication with any possible other – whether a godlike ocean, a time-transcendent Heptapod, or a man on the ‘Moone’.

But while we wait – perhaps in vain – for a signal from the stars, the immediate value of xenolinguistics lies closer to home. By returning to its speculative roots, the science of alien language offers a way to imaginatively demolish the barriers we’ve built between ourselves and other terrestrial beings. We inhabit a world in which algorithms corral us into petty tribalism, populists and fake news stoke xenophobic nationalism, and indifference to the plight of other species sustains both factory farming and anthropogenic mass extinction. Opening ourselves to every conceivable degree of otherness can, even if only abstractly, broaden the scope of our toleration and renew our appreciation for the diversity of aliens that already exist here on Earth.