In September 2023, Linda Coombs published Colonization and the Wampanoag Story with Penguin Random House, about the Wampanoag people’s contact with Europeans. The book was categorised under ‘children’s nonfiction’. A year later, a citizen committee in Montgomery County, Texas, mandated public libraries to move Colonization and the Wampanoag Story from ‘nonfiction’ to ‘fiction’. After much national and international outcry, on 22 October 2024, the Montgomery County Commission reversed the categorisation, and the book was considered ‘nonfiction’ again.

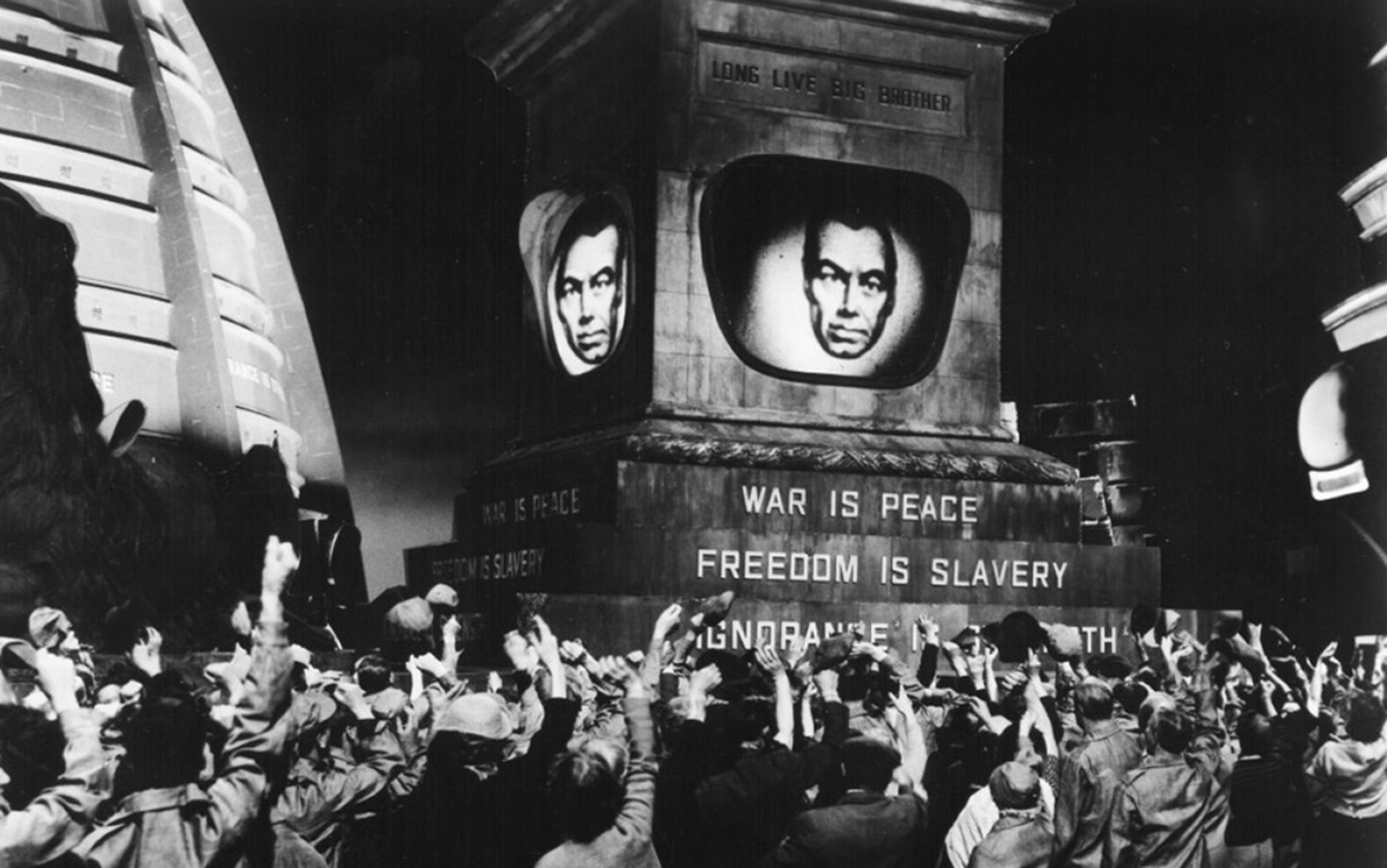

Why did the county care to recategorise a children’s book, especially since the committee didn’t include a single librarian? To call the book ‘fiction’, in this case, was to call it ‘untrue’, a decision undergirded by the desire to resist unflattering portrayals of American history. The power to label books as ‘fiction’ or ‘nonfiction’ is to demarcate what is real and what isn’t, what is true and what is false, what is imagined and what is actual.

When the actor Johnny Depp said, during the 2023 Cannes Film Festival, that the media had been spinning ‘fantastically, horrifically written fiction’ about him, he meant ‘fiction’, of course, as a euphemism for ‘lies’. When the journalist Shakeel Hashim writes that ‘Meta’s AI “safeguards” are an elaborate fiction’, he means that those safeguards are imaginary, unreal, nonexistent. In cases like these, ‘fiction’ contrasts with ‘real’ or ‘true’, therefore becoming synonymous with ‘false’ and ‘fake’. In all these cases, the label ‘fiction’ is applied to shape how we think about reality.

But fiction is different from lies – and hence, labelling Coombs’s book as ‘fiction’, and not ‘bad nonfiction that ought to be pulled from the shelves’, betrays the committee’s intention. They didn’t care about the status of the contents of the book so much as they cared about the contents of what we take to be real and true. All that mattered to them was that it not be considered nonfiction – and if it’s not nonfiction, it must be fiction, right?

This raises a fascinating and surprisingly thorny philosophical question: what distinguishes fiction from nonfiction? What is fiction in the first place? Despite common usage, philosophers agree that we can’t equate ‘fiction’ with ‘false content’. On the one hand, the inclusion of falsity isn’t enough to render a work fiction. Books with false statements – old science textbooks with disproven theories, history books with mistakes, memoirs with contradictory events – don’t change their status from nonfiction to fiction when false content is identified. Instead, we judge them to be bad nonfiction. On the other hand, not all fictions include false content since there are fictions that include only actual events, such as Helen Garner’s The Spare Room (2008), a factual account of the author’s experience of nursing a dying friend. And the fact that historical fiction exists – that a fictional work can be consistent with all known facts, yet still be considered fiction – shows that fiction doesn’t need to include (known) falsity.

What matters for nonfiction is that its content is believed to be true. A creative writing friend of mine told me that writing what one sincerely believes to be true after due diligence in research and introspection is enough to render some content ‘nonfiction’. This means that, strictly speaking, nonfiction can be false but remain ‘nonfiction’ as long as we think it’s true.

Furthermore, to say that ‘nonfiction’ tracks ‘truth’ is misleading because we don’t have an unconditional and overarching interest in truth per se that grounds our protectiveness over what gets called ‘nonfiction’. In ‘The Disinterested Search for Truth’ (1988), Jane Heal shows – convincingly, in my opinion – that one’s seeming pursuit of truth can always be better described as a project that does not involve mention of truth. That is, ‘truth by itself has no motivating power at all.’ We don’t say true things just because they’re true. There are always other considerations.

They targeted a book whose claim to truth practically interfered with their understandings of themselves and the country

When I was a newcomer to philosophy and enamoured with the kind of questions it asked, I thought I was after the Truth – with a capital ‘T’ – and went to grad school in philosophy because I wanted to know what’s True and what’s Really Real. But a single question from a friend dissolved that illusion: do you care about how many stars there are in the Universe right now? I had to admit that I didn’t care, and that alone was enough to show me that perhaps I’m not committed to the True in itself.

If truth were valuable ‘in itself’, then any truth, merely by virtue of being true, would be worth knowing – but this clearly isn’t the case: for instance, someone who keeps a meticulous daily record of the number of cars parked in the nearest lot with no use for the knowledge would strike us as odd. So, that something is true doesn’t justify our interest or commitment. Instead, we care about truths that inform specific enquiries or projects.

What grounds the nonfiction/fiction distinction is not that the former is based on truth or facticity per se, but that the former contributes to how we see the world insofar as it organises the kinds of truths that we care enough about to read and write about. The Montgomery County Commission didn’t initiate a systematic audit of all nonfiction books that might include false or misleading information. Rather, they targeted a book whose claim to truth practically interfered with their understandings of themselves and the country.

Our thoughts about reality and our thoughts about fiction go hand in hand. Of course, sometimes we care about fiction because it lets us entertain a world that is different from ours. But even when it is fiction’s departure from the real world that makes it worthwhile, the departure is measured against the background of the real world. In fact, not only the content of fiction – what we’re able or willing to call ‘fiction’ – but also the nature of fiction – what fiction is – depends on how we think about the real world. A comparative study of the way ‘fiction’ as a concept develops across cultures shows that, whenever a group of people think of reality differently, the nature and function of fiction is understood differently as well. We can observe this by contrasting analytic philosophy of fiction with classical Chinese conceptions of fiction.

In early 20th-century analytic philosophy, fiction crops up as a test case for general theories for meaning, reference and existence. Theories that explain how names refer, or whether ‘existence’ and ‘being’ are the same, had to contend with fictional characters that seemed, in the words of Amie Thomasson, like ‘odd, freakish entities, quite unlike common or garden objects’. Note, for example, that Alexius Meinong’s separation in 1904 of ‘being’ and ‘existence’ explains how Pegasus is a nonexistent object, and that Gottlob Frege’s distinction in 1892 between ‘sense’ and ‘reference’ explains why fictional names seem meaningful even though they’re empty of referent; the name ‘Odysseus’ lacks reference (there is no object in the world that the name refers to) but it has sense (a mode of presentation, a way of being understood).

The trend has continued into the 21st century, and nearly all attempts to define ‘fiction’ involve tools developed from metaphysics, philosophy of language, and philosophy of mind. For example, Richard Ohmann appeals to speech act theory to define fiction as discourse that pretends to assert; David Lewis applies the possible world framework to fiction; Kendall Walton utilises notions of imagination and make-believe to claim fictions are ‘props’ that prescribe certain imaginings; Gregory Currie and Kathleen Stock appeal to intention and imagination, arguing that fiction is a product of a fiction-maker’s intention for the audience to imagine its content. (The exception is Stacie Friend who appeals to the concept of genre to explain what fiction is. It’s interesting to note that the only account that doesn’t draw from ‘core’ areas of philosophy is the one that also denies fiction having any essential or necessary characteristics.)

Fiction occupies the ‘appearance’ side of things, whereas nonfiction occupies the ‘reality’ side

What the methodological trend shows is that the way analytic philosophers have been trying to understand fiction has closely relied on the way we understand existence, language, modality and meaning. We extend theories developed in metaphysics, philosophy of language and philosophy of mind to try to understand fiction and fictional entities. Why are we tempted to investigate the ontological status of fictional characters? It’s because we’re convinced that, whatever they are, they are not like us; they don’t exist in the same way we do. We want to know whether their names function like our names because fictional names seem to pick out something that’s not like objects, places and people in the real world.

Analytic philosophy came to ask the questions it asks because it inherited the ancient Greek idea that some things are less ‘real’ than others. In Anglo-European philosophy, ‘fiction’ is closely connected to what’s imagined – that is, what isn’t taken to be real – because the tradition inherited the appearance/reality distinction from Plato. Fiction occupies the ‘appearance’ side of things, whereas nonfiction occupies the ‘reality’ side. Platonic metaphysics is concerned with unchanging Being, and knowledge pertains only to what’s timelessly true and therefore knowable in a reliable fashion. In Book X of Plato’s Republic, artists and storytelling poets are criticised for creating misleading copies of the physical world, which is already an imperfect copy of the Forms. In Poetics, Aristotle argues that humans possess a natural inclination to imitate nature. Mimesis, or imitation, is at the heart of the Anglo-European understanding of the representational arts, including fiction – and, as a result, concepts that help to adjudicate the relationship between the copy and the real (pretence, imagination and make-believe) become the foundational concepts in analytic philosophy of fiction.

In cultures that don’t take on board a strong reality/appearance distinction, however, ‘fiction’ isn’t understood alongside ‘pretence’ and ‘imagination’ in contrast to ‘the real’. Just like their ancient Greek counterparts, Chinese metaphysicians sought to understand what the world is like and what explains the way the world is. But while the ancient Greeks posited an unchanging ultimate reality that transcends mere phenomena, the ancient Chinese believed that what is ultimate is immanent in the world, and that the Dao (道), the source of all things in the world, is itself constantly changing. This change-forward metaphysics led to a theory of fiction that didn’t contrast fiction against a stable, ‘real’ counterpart.

Recall how Plato relies on the appearance vs reality distinction to argue that what’s ‘really real’ (the unchanging Forms) are beyond our sense perceptions. Humans were meant to use the intellect, and not their senses, since sense data mislead us, while philosophising gives us a chance to grasp what’s beyond phenomena. In contrast, Chinese metaphysicians didn’t think ultimate reality is unchanging. Instead, the dominant view was that reality, including nature, follows consistent patterns (the Dao). What is ‘empty’ or ‘unreal’ was seen as the generator of all things, and all things were considered equal in significance since they are all manifestations of changing patterns.

The Chinese word for ‘fiction’ (xiaoshuo, 小說) literally means ‘small talk’ or ‘small sayings’. Chinese literary culture had a rigid hierarchy of discourses, with Confucian classics and official histories at the top of the pyramid, while imaginative narrative texts like xiaoshuo were placed at the bottom. However, it would be misleading to say that xiaoshuo was denigrated because it was imaginative, whereas philosophical texts and histories were elevated because they were ‘real’. Since Chinese metaphysics didn’t posit a fixed, transcendent reality, reality was understood to be an ever-changing process, and so the categories themselves couldn’t be based on inherent, necessary or fixed essences but on functions and behavioural tendencies. The difference between discourses labelled ‘xiaoshuo’ and ‘great learning’ (Confucian classics and histories) wasn’t that one is unreal or imagined while the other is real. All discourse was understood as an account of the world, and the difference between ‘small talk’ and ‘great learning’ was the extent to which it was adopted to organise how people lived. Xiaoshuo wasn’t understood in contrast to reality, and it wasn’t metaphysically second class. It was at the bottom of the discourse hierarchy because its function wasn’t as grand as the classics’.

Discourse that posed trouble for social and political interpretation was considered ‘xiao’ (small)

Because the Confucian classics were considered canon, there was little room for textual scholarship in philosophy (beyond commenting). But history had to be continually produced, so history and historiography became the most revered genre, and eventually the paradigm of all culture discourse. Again, a Western-minded explanation for the xiaoshuo/history distinction would appeal to the former being fake or imagined, and the latter being real. But to do so would be to attribute inappropriate metaphysical commitments to the Chinese framework. Besides, the xiaoshuo/imaginary, history/actual, pairings aren’t exemplified in the categorised works themselves. Early forms of fiction included reports of what occurred, and official histories made room for invention and fabrication. Instead, I believe that xiaoshuo’s separation from history and historiography, and the resulting denigration, had to do with xiaoshuo material’s interpretive difficulties rather than the fact that fabrication was involved. Xiaoshuo’s weakness wasn’t tied to its being imagined or untrue, but to it being ‘unsuitable’ as a vehicle for meaning.

History was prioritised as a literary genre not because it talked about true things, but because it provided the stable basis for literary activity, a continual process of meaning-making through writing, reading and interpreting. And history was interpretable, and therefore a suitable means for signification, because the ‘Mandate of Heaven’ posited that the unfolding of events reflected the ruler’s political legitimacy (or lack thereof). But xiaoshuo didn’t have such interpretive weight because much of its early examples were report-like narratives that involved the supernatural (ghosts, abnormalities, miracles, etc). It’s interesting to note that while categorised as xiaoshuo, these ‘records of the strange’ (zhiguai) were considered ‘leftover history’, understood not as fabricated stories but as an offshoot of historical writing that was worth preserving due to their contribution to knowledge but not suitable for inclusion in official history given its weirdness.

So, my suggestion is that discourse that posed trouble for meaningful social and political interpretation was considered insignificant, therefore ‘xiao’ (small). Scholars were unsure what, if anything, we can take as a larger message from these reports, therefore they were separated from history. The important consideration wasn’t that they weren’t real; it was just that their points were unclear. The distinction between xiaoshuo and history wasn’t about inviting imagination but about whether the discourse belonged to a stable, communal interpretive framework. Since there is no unchanging reality that fiction is contrasted to, xiaoshuo doesn’t invite mimesis as an operative concept. And since fiction isn’t assumed to be a copy of reality, there is no theoretical apparatus aimed to clearly distinguish what’s real from what’s fictional.

To understand the importance of how a culture’s metaphysical commitments affect its view of fiction, imagine how two different communities might come to create a wooden duck. A community that hunts ducks will use the wooden duck as a decoy that lures real ducks to a particular location. For them, the wooden duck’s ‘point’ is determined in response to its similarities and differences to a real duck: it must be similar enough to trick other ducks into thinking it’s a real duck, but it must be different enough for humans to know not to shoot it. Its nature is understood in relation to a ‘real’ organic duck; a wooden duck is a mere decoy since it contrasts with the living version. The point of asking about the nature of the duck is to ask what one is meant to do with the object.

Now, contrast the hunting community with another community that approaches the wooden duck as an aesthetic object. The wooden duck’s ‘point’ is determined in relation to the shape and colour that constitute the duck, and different views might form depending on their reactions to the duck: it must be beautiful, or interesting, or compelling in some way to merit attention. Whatever we say about the object’s nature responds mostly to how people understand and react to the duck, and not some independent standard against which the duck might be compared. So here, too, asking about the wooden duck’s nature presupposes, or at least develops in tandem with, what we’re meant to do with the object.

What the wooden ducks show is that the kinds of questions we ask of the same object (or concept) can differ depending on the background practices and commitments that we bring to it. Each culture’s understanding of fiction arises from their pre-existing commitments about what the world is like. ‘Fiction’ is difficult to define because fiction is not a standalone concept with its own intrinsic properties, but a concept that responds to a given metaphysical system. Comparing Anglo-European and Chinese thoughts on fiction show how metaphysical assumptions affect the way we theorise fiction. Metaphysics begins from our observations about the world and is sustained by the desire to make sense of the world. The metaphysical concepts we devise in turn affect the way we represent the world, so it is no surprise that fiction develops in response to the metaphysical frameworks we begin with.

There isn’t a single definition of ‘fiction’ that can be applied transculturally

Fiction is part of a rich and varied cultural practice, so theorising fiction ought to be sensitive not only to the metaphysical frameworks, but also to the sociohistorical frameworks in which fiction is conceived, produced and consumed. But perhaps more importantly, being clear-eyed about the dependent, contextual and even reactive development of fiction allows our philosophising about the nature of fiction to be conducted from a more informed place that is aware of why we ask the questions we ask. We can be clearer on what the stakes are in our fiction theorising, and this in part lets us see how fiction can – and has been – put to work in theory and practice. The Montgomery County Commission’s attention was on works whose content challenged their favourable picture of American history. Attempting to recategorise a book from ‘nonfiction’ to ‘fiction’ on the basis of its unwelcome content shows that ‘fiction’ had been used as a practical tool for image management. Noting the variety of ways in which works of fiction had been put to aesthetic, social, political and moral uses shows that the Texan committee’s use of fiction is more blatant than usual, but not extraordinary.

Current and historical practices, and the theories that propped them up, point towards the conclusion that there is no universal concept of fiction. It might be true that all human cultures tell inventive stories, but that isn’t enough to claim that there is a single definition of ‘fiction’ that can be applied transculturally. ‘Fiction’ is necessarily a thick term insofar as it presupposes some metaphysical framework that separates fiction from other genres of writing.

So, instead of asking how fiction might be defined (ahistorically, logically), we should ask what work we want fiction to do. Our questions about fiction come from identifiable metaphysical starting points. If we find ourselves continuing to crave a definition of fiction, we should also ask what need it will meet: what theory of fiction do we require to solve current problems?

In 21st-century Anglophone media, invoking fiction allows speakers to dismiss claims without incurring social cost. To get ahead of potential defamation lawsuits, movies and TV shows remind their viewers of the fictional status of the work but, outside of those contexts, fiction is often invoked to mean something like ‘hearsay’, ie, a claim that cannot be substantiated and therefore ought to be dismissed. If we’re asking about the nature of fiction, then we should do so with an eye towards producing an understanding of fiction that wouldn’t allow bad actors to lie and successfully evade punishment by insisting they were ‘only making fiction’, or dismiss unfavourable claims as ‘fiction’ as if they can be the final arbiter, or as if fiction can be peddled as fact without ramifications.

One of the most interesting – and promising – features of fiction is that it creates a space between the ‘true’ and the ‘false’, between ‘real’ and ‘imaginary’. Good fiction tends to destabilise such dichotomous ways of approaching the world through thoughtful content, innovative form, or self-referentiality. Is there some special work we can expect of fiction, such that we can rethink its nature and function towards that end? The fiction/nonfiction distinction is one worth keeping, and philosophers of fiction continue to have their work cut out for themselves.