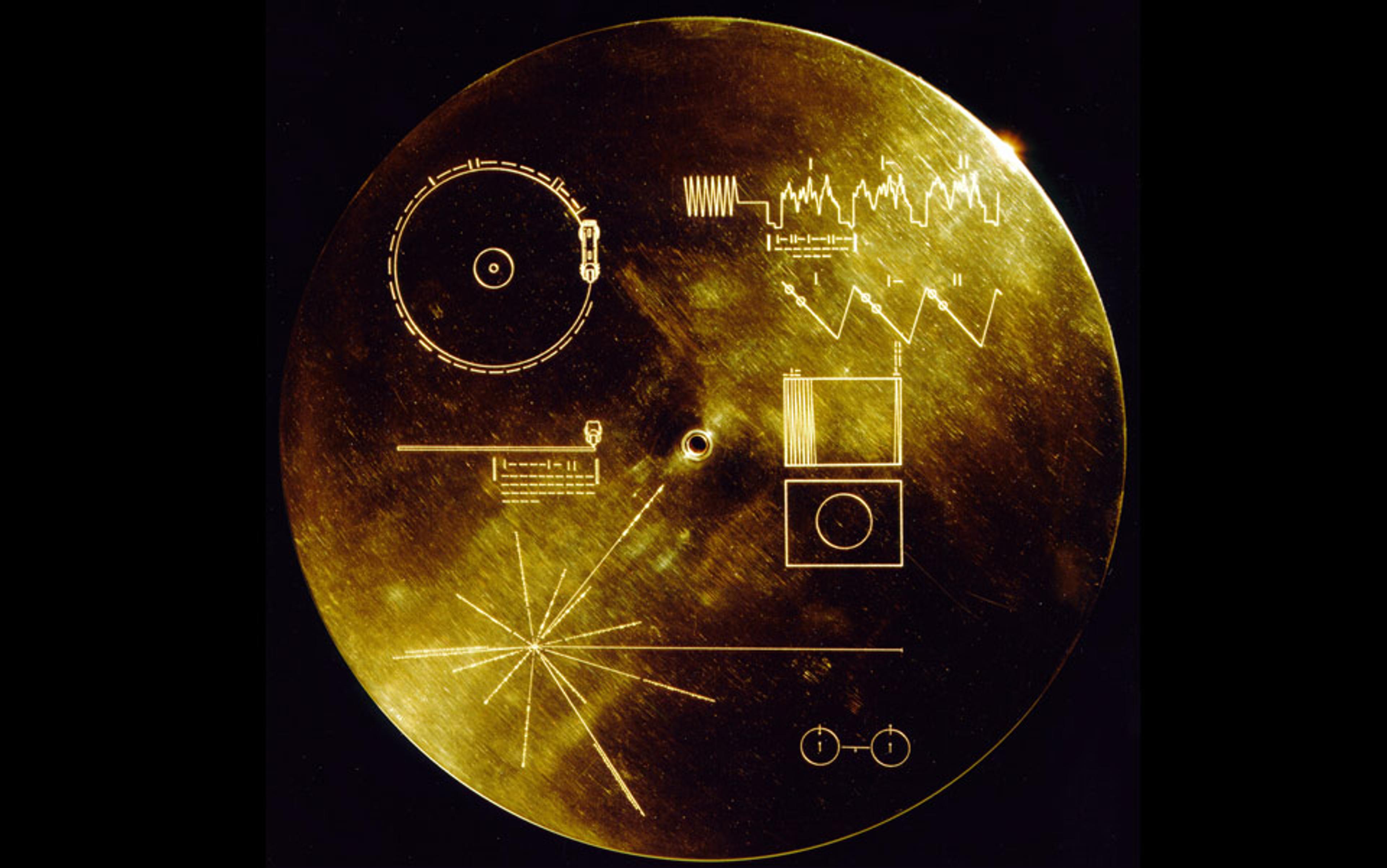

On St Valentine’s Day 1990, NASA’s engineers directed the space-probe Voyager 1 – at the time, 6 billion kilometres (3.7 billion miles) from home – to take a photograph of Earth. Pale Blue Dot (as the image is known) represents our planet as a barely perceptible dot serendipitously highlighted by a ray of sunlight transecting the inky-black of space – a ‘mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam’, as Carl Sagan famously put it. But to find that mote of dust, you need to know where to look. Spotting its location is so difficult that many reproductions of the image provide viewers with a helpful arrow or hint (eg, ‘Earth is the blueish-white speck almost halfway up the rightmost band of light’). Even with the arrow and the hints, I had trouble locating Earth when I first saw Pale Blue Dot – it was obscured by the smallest of smudges on my laptop screen.

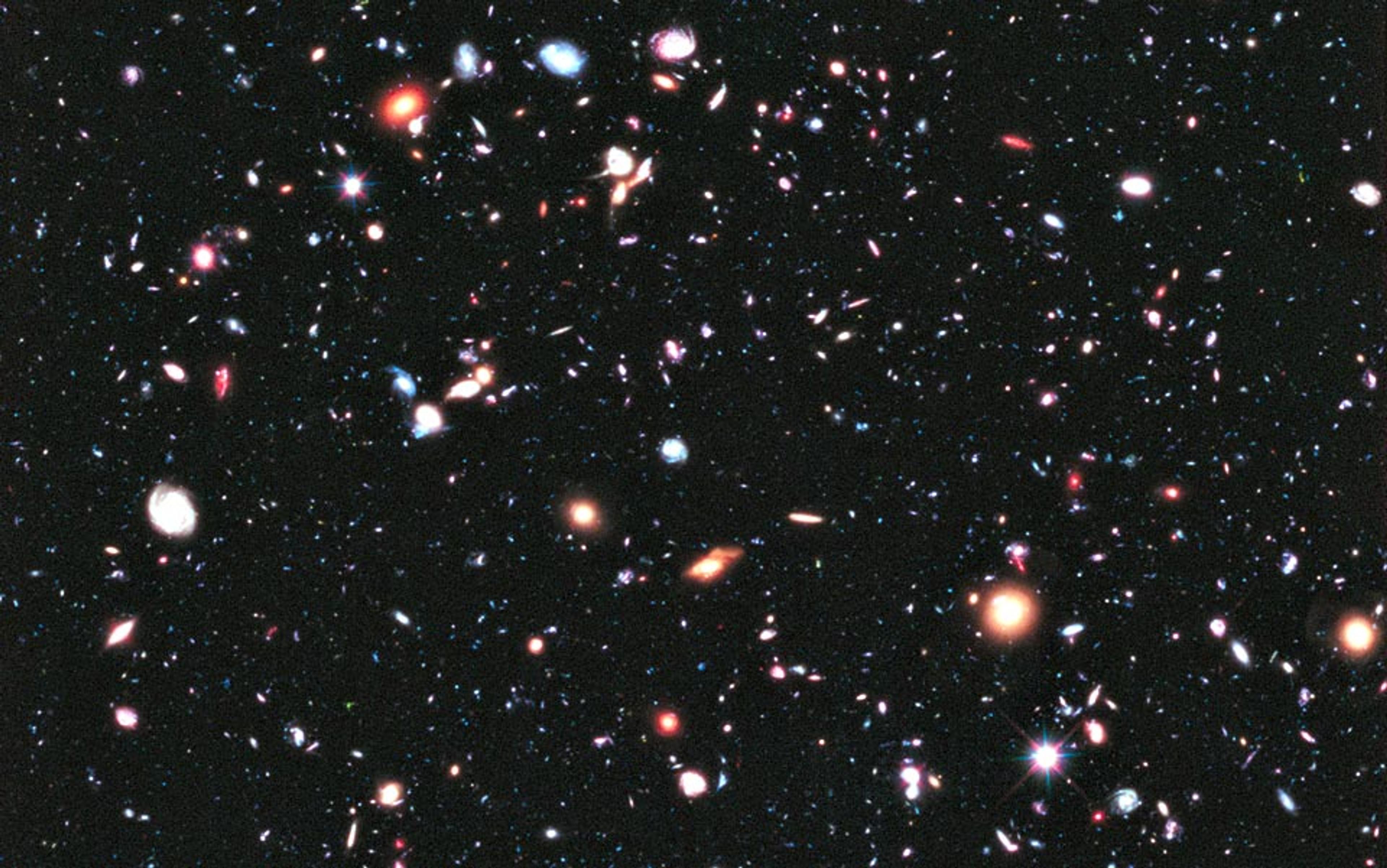

The striking thing, of course, is that Pale Blue Dot is, astronomically speaking, a close-up. Were a comparable image to be taken from any one of the other planetary systems in the Milky Way, itself one of between 200 billion to 2 trillion galaxies in the cosmos, then we wouldn’t have appeared even as a mote of dust – we wouldn’t have been captured by the image at all.

Pale Blue Dot inspires a range of feelings – wonderment, vulnerability, anxiety. But perhaps the dominant response it elicits is that of cosmic insignificance. The image seems to capture in concrete form the fact that we don’t really matter. Look at Pale Blue Dot for 30 seconds and consider the crowning achievements of humanity – the Taj Mahal, the navigational exploits of the early Polynesians, the paintings of Georgia O’Keeffe, the inventions of Leonardo da Vinci, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, Cantor’s theorem, the discovery of DNA, and on and on and on. Nothing we do – nothing we could ever do – seems to matter. Pale Blue Dot is to human endeavour what the Death Star’s laser was to Alderaan. What we seem to learn when we look in the cosmic mirror is that we are, ultimately, of no more significance than a mote of dust.

Contrast the feelings elicited by Pale Blue Dot with those elicited by Earthrise, the first image of Earth taken from space. Shot by the astronaut William Anders during the Apollo 8 mission in 1968, Earthrise depicts the planet as a swirl of blue, white and brown, a fertile haven in contrast to the barren moonscape that dominates the foreground of the image. Inspiring awe, reverence and concern for the planet’s health, the photographer Galen Rowell described it as perhaps the ‘most influential environmental photograph ever taken’. Pale Blue Dot is a much more ambivalent image. It speaks not to Earth’s fecundity and life-supporting powers, but to its – and, by extension, our – insignificance in the vastness of space.

Earthrise, taken on 24 December 1968 by Apollo 8 astronaut William Anders. Courtesy NASA

But what, exactly, should we make of Pale Blue Dot? Does it really teach us something profound about ourselves and our place in the cosmic order? Or are the feelings of insignificance that it engenders a kind of cognitive illusion – no more trustworthy than the brief shiver of fear you might feel on spotting a plastic snake? To answer that question, we need to ask why Pale Blue Dot generates feelings of cosmic insignificance.

One account of the feelings elicited by Pale Blue Dot begins in the 17th century, with the French scientist and philosopher Blaise Pascal. Pascal was born in 1623, a mere 14 years after Galileo directed the first telescope heavenwards. Galileo’s observations not only confirmed Copernicus’s heliocentric conception of the solar system and revealed ‘imperfections’ in the celestial bodies (such as the Moon’s craters and mountains), they also revealed countless stars invisible to the naked eye. It was a moment of profound upheaval for humanity’s self-understanding, and many of the reflections recorded in Pascal’s Pensées – a series of notebook jottings published only after Pascal’s death – seem to have been prompted by the new astronomy:

When I consider the short span of my life absorbed into the preceding and subsequent eternity … the small space which I fill and even can see, swallowed up in the infinite immensity of spaces of which I know nothing and which know nothing of me, I am terrified, and surprised to find myself here rather than there, for there is no reason why it should be here rather than there, why now rather than then. Who put me here? On whose orders and on whose decision have this place and time been allotted to me?

(from the Honor Levi translation of Pascal’s Pensées, 1995)

But it is this line from the Pensées – ‘The eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me’ – that perhaps best captures the feeling of cosmic insignificance. Indeed, the line could well serve as a caption for the Pale Blue Dot. For Pascal, the night sky wasn’t merely awe-inspiring – it was terrifying. And it was terrifying not (just) because it was infinite, but because it was ‘silent’.

Pascal doesn’t tell us what he meant by the silence of space, but there is reason to suspect that at least part of the answer is theological. The cosy, well-ordered universe of the Middle Ages had been replaced by a universe that was not only vastly bigger but seemed to be ruled by chance and contingency. ‘Who put me here?’ Pascal asks. ‘Perhaps no-one,’ one can almost hear him answer. The silence of space is the silence of the Universe in response to the question of God.

It is Pascal’s terror of space that has reverberated down the ages

Of course, Pascal himself was no atheist, and there are passages in the Pensées that suggest a very different attitude to the vastness of space:

So let us contemplate the whole of nature in its full and mighty majesty, let us disregard the humble objects around us, let us look at this scintillating light, placed like an eternal lamp to illuminate the universe. Let the earth appear a pinpoint to us beside the vast arc this star describes, and let us be dumbfounded that this vast arc is itself only a delicate pinpoint in comparison with the arc encompassed by the stars tracing circles in the firmament.

Pascal goes on to suggest that the very fact that our imagination ‘loses itself’ in the face of such thoughts is itself ‘the greatest perceivable sign of God’s overwhelming power’.

But it is Pascal’s terror of space that has reverberated down the ages. One can hear its echo in Joseph Conrad’s novel Chance (1913), in which the narrator describes ‘one of those dewy, clear, starry nights, oppressing our spirit, crushing our pride, by the brilliant evidence of the awful loneliness, of the hopeless obscure insignificance of our globe lost in the splendid revelation of a glittering, soulless universe.’

So here is one account of why Pale Blue Dot elicits the feelings it does. It indicates (reminds us?) that we are on our own. The Universe is not the product of divine plan; or at least, if it is, it is not a plan that takes our interests seriously.

Let’s suppose – if only for the sake of argument – that this account goes at least some way towards explaining why Pale Blue Dot elicits the feelings that it does. What, then, should we make of those feelings?

That, of course, turns on the question of how God’s inexistence would bear on human significance. Some assume that God is required for cosmic significance. Nothing could really matter in a world without God, and if nothing really matters then we don’t matter. If that’s right, then the feelings elicited by Pale Blue Dot wouldn’t be illusory. Instead, they would reveal a profound – and perhaps deeply unsettling – truth: from a cosmic point of view, we really are insignificant.

But the idea that significance requires God is deeply puzzling. If the beauty, knowledge and creativity that we see around us don’t really matter in and of themselves, how could the addition of God help? Indeed, it’s surely more plausible to suppose that it’s God’s presence rather than God’s absence that poses the more serious threat to human significance. After all, the beauty, knowledge and creativity that we’ve produced surely pales in comparison with that traditionally ascribed to God. As a 21st-century psalmist might put it, what is the sum total of human knowledge when set against God’s wisdom? What is the beauty of the Taj Mahal, A Love Supreme or the paintings of O’Keeffe when placed against the grandeur of the Horsehead Nebula in the Orion constellation?

The Horsehead Nebula captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. Courtesy NASA, ESA and the Hubble Heritage Team

Theology provides one lens through which to view the sense of cosmic insignificance; accounts of our experience of space provide another. Not the space of astronomy and inter-planetary probes, but the space of ordinary perceptual terrestrial environment.

It’s a familiar thought that ordinary modes of experiencing space (and, indeed time) are structured in terms of the human body and its capacities. One sees a door as 10 steps away and the fence as 20 steps away. As we grow and our limbs lengthen, the sense of the space around us also changes. This explains the common experience of visiting one’s childhood home and neighbourhood, and finding them much smaller than expected. Distances that had required 10 steps to traverse as a child can now be crossed in only five; doorframes that once towered high above one’s head can now be reached with ease.

The bodily structure of perceptual experience is reflected in our units of measurement. Ancient Mesopotamian builders used the cubit, determined by the length of the forearm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. More familiar to us is the foot, a central unit of measurement in Ancient Rome, Greece and China, and based of course on the length of the human foot. Sometimes, of course, we trade the dimensions of the human body for those of other animals. In the world of children’s books, skyscrapers are measured in terms of giraffes (‘the Burj Khalifa is 166 giraffes tall’) and the weight of construction vehicles is given in terms of elephants (‘the Bagger 293 weighs 2,580 elephants’). Giraffes and elephants may not make for good units of scientific measurement, but they do provide young children with a sense of an object’s properties.

One wants to ask how far a light year or astronomical unit is in real money

Our perceptual faculties enable us to grasp the scale of most built environments, but they are ill-equipped to capture the enormity of nature. To fully appreciate the size of the Grand Canyon, you need to hike down into it – simply looking won’t do the trick. The towering peaks of the Karakoram, the endless sand dunes of the Empty Quarter, the vast glaciers of Antarctica speak to nature’s ability to overwhelm our perceptual capacities. In James Joyce’s novel Ulysses (1920), Buck Mulligan, gazing out over Dublin Bay, refers to ‘the scrotumtightening sea’.

But to fully appreciate the limitations of the human body as a scale for nature, you need to cross the Kármán line, the boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space. At its closest, Venus is 38 million kms away. (That’s around 7.6 billion giraffe-lengths.) Neptune, at its furthest, is 4.7 billion kms (around 940 billion giraffes) from us. It is 40,208,000,000,000 km from the Sun to Proxima Centauri, the next-nearest sun to us. Taken with an exposure time of over 11 days, the Hubble Ultra Deep Field captured a region of the night sky smaller than a grain of sand held at arm’s length – and yet it depicts around 10,000 galaxies.

These are unimaginably big numbers. We might be able to recite them, but few of us – other than mathematicians and astronomers, perhaps – can truly grasp them. (And note how natural it is to describe understanding in terms of bodily activity – ‘grasping’.)

One can, of course, avoid the need for big numbers by trading familiar units for unfamiliar ones – as science does. Instead of measuring the distance to Proxima Centauri in terms of kilometres, astronomers use astronomical units (the average distance between Earth and the Sun – around 150 million km) or light-years (multiples of the distance light travels in a year – around 9.5 trillion km). That gives us a more manageable way of dealing with astronomical distances, but it doesn’t help us to truly grasp the immensity of the cosmos. One wants to ask how far a light year or astronomical unit is in real money.

But if this is what explains our feelings of cosmic insignificance – and it’s likely to be part of the story – then it’s not clear why we should pay those feelings any heed. So what if our perceptual experiences cannot accommodate the dimensions of the cosmos? Our perceptual systems have been designed by evolution to help us navigate ordinary terrestrial environments, their job isn’t to track what matters. We might be unnerved by the amount of real estate we occupy, but such feelings provide no insight into our cosmic significance.

The two accounts of Pale Blue Dot that we’ve examined are curiously silent about one crucial feature of the image: it is not just an image of the vast emptiness of space, it’s an image of the vast emptiness of space in which we appear. It’s not an image from Earth but an image of Earth. Equally crucially, it’s an image in which Earth – the very object that provides the context for everything that matters to us – is barely perceptible, no more salient than a mote of dust.

Salience matters because it’s a signal from our senses: ‘This is significant – pay attention to it.’ From birth, our senses alert us to the presence of features that are important to us – human faces, our mother’s voice, the speech of those around us. The mechanisms that track perceptual salience evolve as we ourselves develop, but they continue to function as sentries, alerting us to what matters. The smell of smoke, loud sirens, sudden movements – these phenomena are all attention-grabbing. It doesn’t matter how engaging your current conversation is, if someone on the other side of the room utters your name, you’ll have a hard time not tuning in and eavesdropping on their conversation. The corollary, of course, is that what isn’t attention-grabbing doesn’t strike us as significant.

And Earth as it appears in Pale Blue Dot is pretty much as unobtrusive, as non-attention-grabbing, as overlook-able as it is possible to be. (Indeed, even the hint of perceptual salience – the sunbeam in which Earth is suspended – isn’t a genuine feature of Earth’s position in the cosmos but an artefact of the image itself.) Pale Blue Dot seems to capture the fact that, from a truly objective point of view – the view from ‘nowhere’, as we might put it – we aren’t attention-grabbing. And if we aren’t attention-grabbing (it’s natural to assume), then we’re not genuinely significant.

‘Small’, the image might seem to say, ‘but enormously significant’

But if this account explains why Pale Blue Dot elicits feelings of cosmic insignificance, it also shows why those feelings are not trustworthy. Pale Blue Dot may have been taken from a distance of 6 billion km, but it does not provide a ‘God’s eye’ view of the cosmos. It is, of course, an image, and every image conceals as much as it reveals.

Return to the contrast between Pale Blue Dot and Earthrise. Pale Bue Dot reveals something (albeit only a little) of the vastness of the cosmos in which Earth is located; Earthrise conceals this fact. But Earthrise reveals features that are concealed by Pale Blue Dot: Earth’s life-supporting capacities. Neither provide the ‘complete image’ of Earth from outer space – there is no such image.

Once we appreciate this fact, we can start to consider new perspectives on the question of cosmic significance.

Here’s one. Suppose that Voyager 1 had been equipped with a device designed to detect consciousness-supporting planets. And suppose that the images produced by this device marked the presence of such planets with bright red pixels. Had Voyager 1 directed its ‘consciousness camera’ Earthwards, we would have been as attention-grabbing as the scrape of a chair in a performance of John Cage’s 4’33”. The feelings generated by Bright Red Dot (as we might call this image) would surely be very different from those elicited by Pale Blue Dot. ‘Small’, the image might seem to say, ‘but enormously significant.’

Does that mean we are significant? Maybe not. Suppose that we used our ‘consciousness camera’ to map not just our corner of the solar system but the entire Universe. What kind of image might it produce?

One possibility is that Earth would emerge as the sole red dot in a vast expanse of blackness. (‘Nothing like us anywhere,’ we might say to ourselves with justifiable pride.) But the odds of that are surely low – perhaps vanishingly so. Astronomers suggest that there may be as many as 50 quintillion (50,000,000,000,000,000,000) habitable planets in the cosmos. What percentage of those planets actually sustain life? And, of those that sustain life, what percentage sustain conscious life? We don’t know. But let’s suppose that consciousness is found in only one of every billion or so life-supporting planets. Even on that relatively conservative assumption, there may be as many as 50 billion consciousness-supporting planets. Earth, as viewed through our consciousness camera, would be just one more red dot among a vast cloud of such dots.

Human creativity might be unmatched on this planet; it may even be without peer in the Orion arm of the Milky Way. But, given the numbers, we’re unlikely to be eye-catching from a cosmic point of view.