‘I assume that the reader is familiar with the idea of extra-sensory perception … telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition and psycho-kinesis. These disturbing phenomena seem to deny all our usual scientific ideas … Unfortunately the statistical evidence, at least for telepathy, is overwhelming … Once one has accepted them it does not seem a very big step to believe in ghosts and bogies.’

These words weren’t published in the pages of an obscure occult journal or declared at a secret parapsychology conference. They weren’t written by a Victorian spiritualist or a séance attendee. In fact, their author is Alan Turing, the father of computer science, and they appear in his seminal paper ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ (1950), which describes the ‘imitation game’ (more commonly known as the ‘Turing test’) designed to establish whether a machine’s intelligence could be distinguished from that of a human.

The paper starts by setting up the now-famous thought experiment: a human, a machine, and an observer who asks questions. If the observer cannot work out which one is which based on their responses, the machine has passed the test: its intelligence is indistinguishable from that of a human mind. The vast majority of the paper addresses various objections against the experiment from mathematics, philosophy of mind, or from those sceptical about the power of computers.

But, about two-thirds of the way through the paper, Turing addresses an unexpected worry that might disrupt the imitation game: telepathy. If the human and the observer could communicate telepathically (which the machine supposedly could not do), then the test would fail. ‘This argument is to my mind quite a strong one,’ says Turing. In the end, he suggests that, for the test to work properly, the experiment must take place in a ‘telepathy-proof room’.

Why did Turing feel the need to talk about telepathy? Why did he consider extrasensory perception a serious objection to his thought experiment? And what about his peculiar mention of ghosts?

At the turn of the 20th century, England was obsessed with spiritualism. People from all strata of society were fascinated by séances, after-death survival, ghosts, precognitions, and clairvoyance. Famous mediums such as Eusapia Palladino, Ada Goodrich Freer and Etta Wriedt travelled around Europe to demonstrate their powers to levitate tables, communicate with spirits of the dead, or produce ‘ectoplasm’, a mysterious half-material, half-spiritual substance coming out of one or more of the medium’s bodily orifices. Not infrequently for a hefty fee, of course.

‘Ectoplasm’. Courtesy the Cambridge University Library

From an album of spirit photographs (1872) by Frederick Hudson. Courtesy the Met Museum, New York

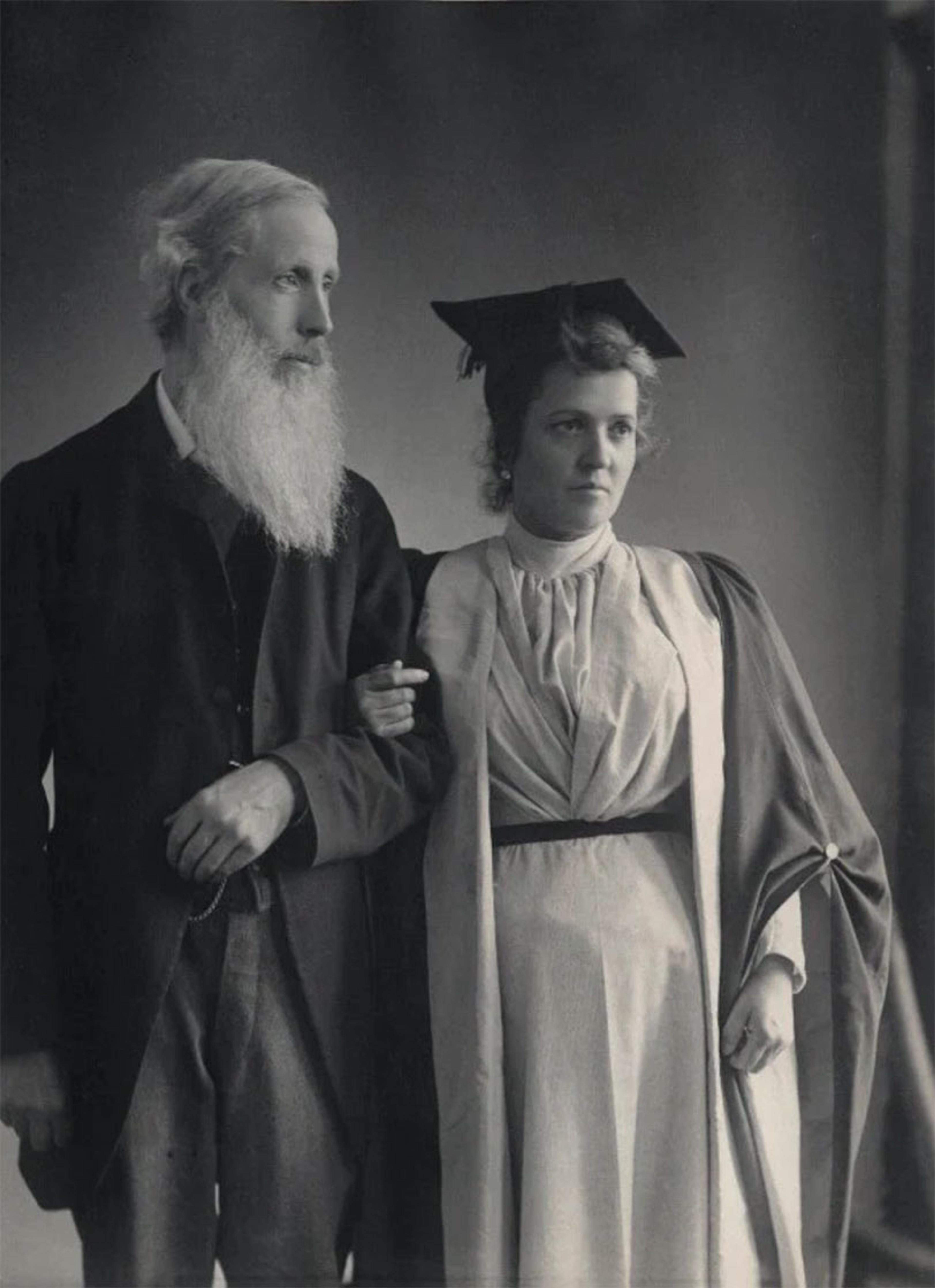

In 1882, a group of scholars associated with Trinity College, Cambridge, founded the Society for Psychical Research, a learned society whose aim was to study these phenomena with scientific rigour. Over the course of its existence, the society counted among its members some of the brightest minds of the time, including the author Arthur Conan Doyle and the physicist J J Thomson. Its members displayed various levels of commitment to the phenomena of the séance room. Some were very committed, such as the physicist Oliver Lodge, who wrote a highly influential book containing records of séances where he communicated with his son who was killed in action during the First World War. Some were much more sceptical, like Eleanor Sidgwick, a physics researcher and the principal of Newnham College, Cambridge, or John Venn, the inventor of the Venn diagram. Despite the differences in their level of commitment to the reality of paranormal occurrences, this heterogeneous group of scholars agreed that these phenomena deserved scholarly attention.

Ectoplasm turned out to be cheesecloth. Levitating tables were discovered to be attached to fishing wire

A high number of professional philosophers either joined the society or engaged with its findings. The ethicist Henry Sidgwick (Eleanor’s husband) was one of its founders, together with F W H Myers, the inventor of the word ‘telepathy’ and an unusually committed member: according to at least one report, he continued his involvement after his death, sending messages from the beyond via various mediums (a sort of extreme version of the professor emeritus who occasionally drops by the department). Such esteemed philosophers as Henri Bergson, William James and F C S Schiller were each elected president of the society. Many other philosophers, such as May Sinclair, were regular members.

Henry Sidgwick and Eusapia Palladino (c1890) photographed by Eveleen Myers (née Tennant). Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

The society was not cloistered off from the rest of the academic world. Discussions about psychical phenomena spilt over into the most respected philosophy journals of the period. For example, one of the 1902 issues of The Monist included a paper entitled ‘Spirit or Ghost’ by Paul Carus (the journal’s editor), and musings about life after death, precognitions and telepathy also appeared in the journals Mind, Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society and Philosophy. Soon after the turn of the century, popular interest in psychical research began to wane. Ectoplasm turned out to be cheesecloth. Levitating tables were discovered to be attached to fishing wire. Ghosts emerging, in near complete darkness, from ‘spiritual cabinets’ looked suspiciously like the mediums themselves dressed in white robes. But the philosophical fascination with paranormal phenomena continued. Long after psychical research had been pushed out of biology, psychology and physics departments to the margins of academia, professional philosophers continued theoretical discussions about its findings unabated. There is no better example of the symbiosis of academic philosophy and psychical research than C D Broad.

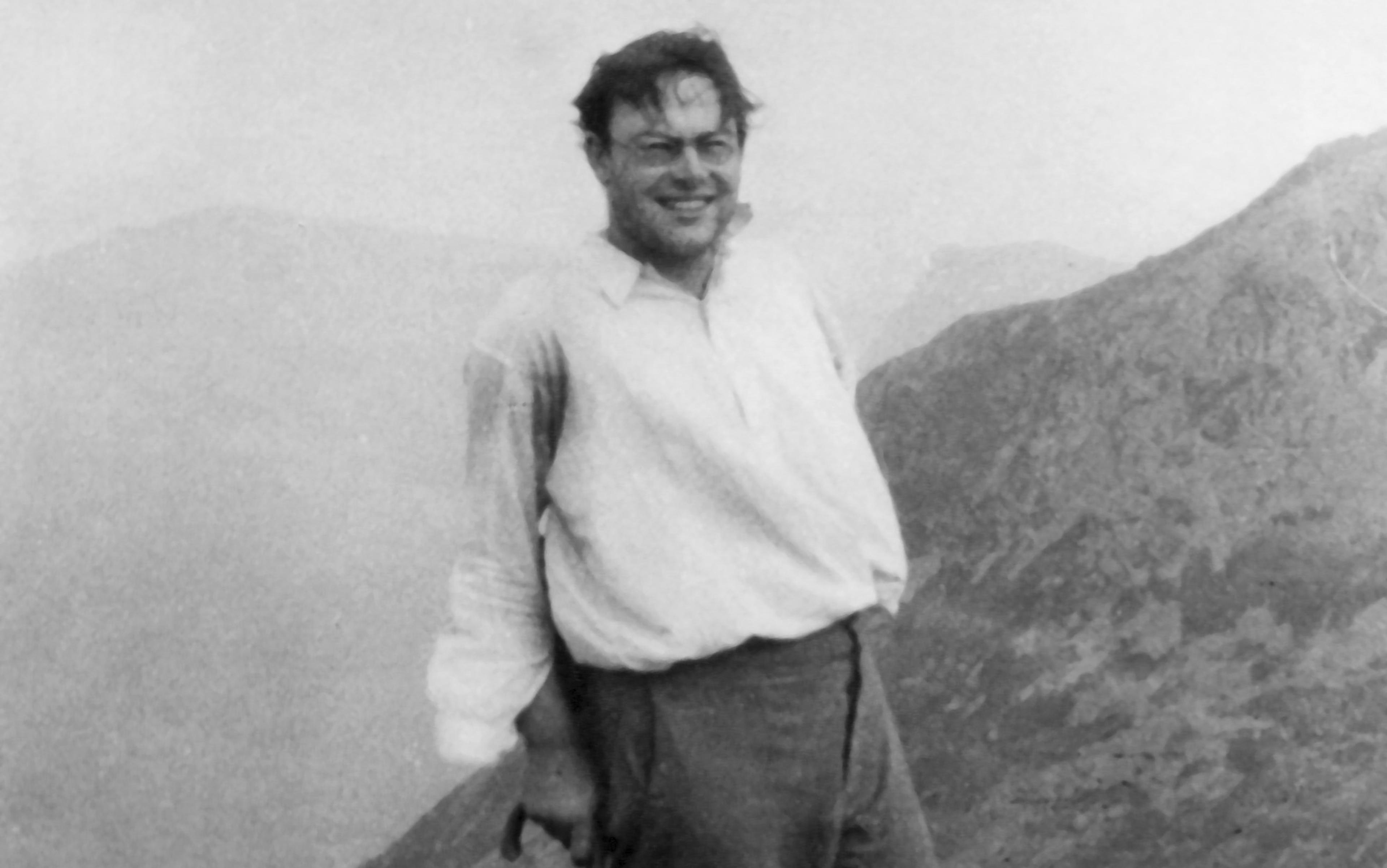

Charlie Dunbar Broad (1887-1971) was a Sidgwick Lecturer and later Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy at Cambridge. He published extensively on ethics and the history of philosophy, though today he is known as one of the most influential 20th-century philosophers of time. He was also one of the first openly gay philosophers in Britain.

Charlie Dunbar Broad (1930) photographed by Walter Stoneman. Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

As you leaf through the Broad papers at Trinity College, notes on logic, metaphysics and time sit side by side with horoscopes he made for his friends, letters from people reporting ghost sightings, and extensive reflections on papers published in a wide range of parapsychology journals. Their physical coexistence in the archive reflects the two-way influence between Broad’s philosophy and his interest in the paranormal. His philosophical views shaped his approach to psychical phenomena – but psychical phenomena, as we will see, also influenced his philosophy. In either case, he did not think that the paranormal was anything to scoff at.

Of particular interest to psychical researchers were ‘precognitive dreams’, dreams that contained future events

The Society for Psychical Research elected him president twice, in 1935 and again in 1958. Over the course of his career, he published innumerable papers on telepathy, clairvoyance, poltergeists, after-death survival and precognitive dreams. His library featured books on astral projections, astrology, human immortality and vampirism. In the typescript of his autobiography, he says: ‘I do not know when or how [my interest] began, but I can hardly remember a time when it did not exist.’

Broad published his views on the paranormal not just in psychical research periodicals, but also in key philosophy journals. Despite being infamous for his interest in psychical research, his writings on the topic, taken as a whole, are highly ambiguous. In his publications for the society, he made it very clear that he believed in the existence of psychical phenomena. In respectable philosophical journals, however, he went for a more sceptical tone and mainly focused on the philosophical implications that these phenomena would have if they turned out to be real.

A good example of his application of philosophical machinery to psychical research is his work on precognition, the purported ability to see the future. Of particular interest to psychical researchers were ‘precognitive dreams’, dreams experienced by ordinary people that contained future events. The society had been fascinated by precognitions ever since its foundation, but what really intensified this interest was a popular publication by an academic outsider who was to have a huge impact on Broad’s later views about the nature of time.

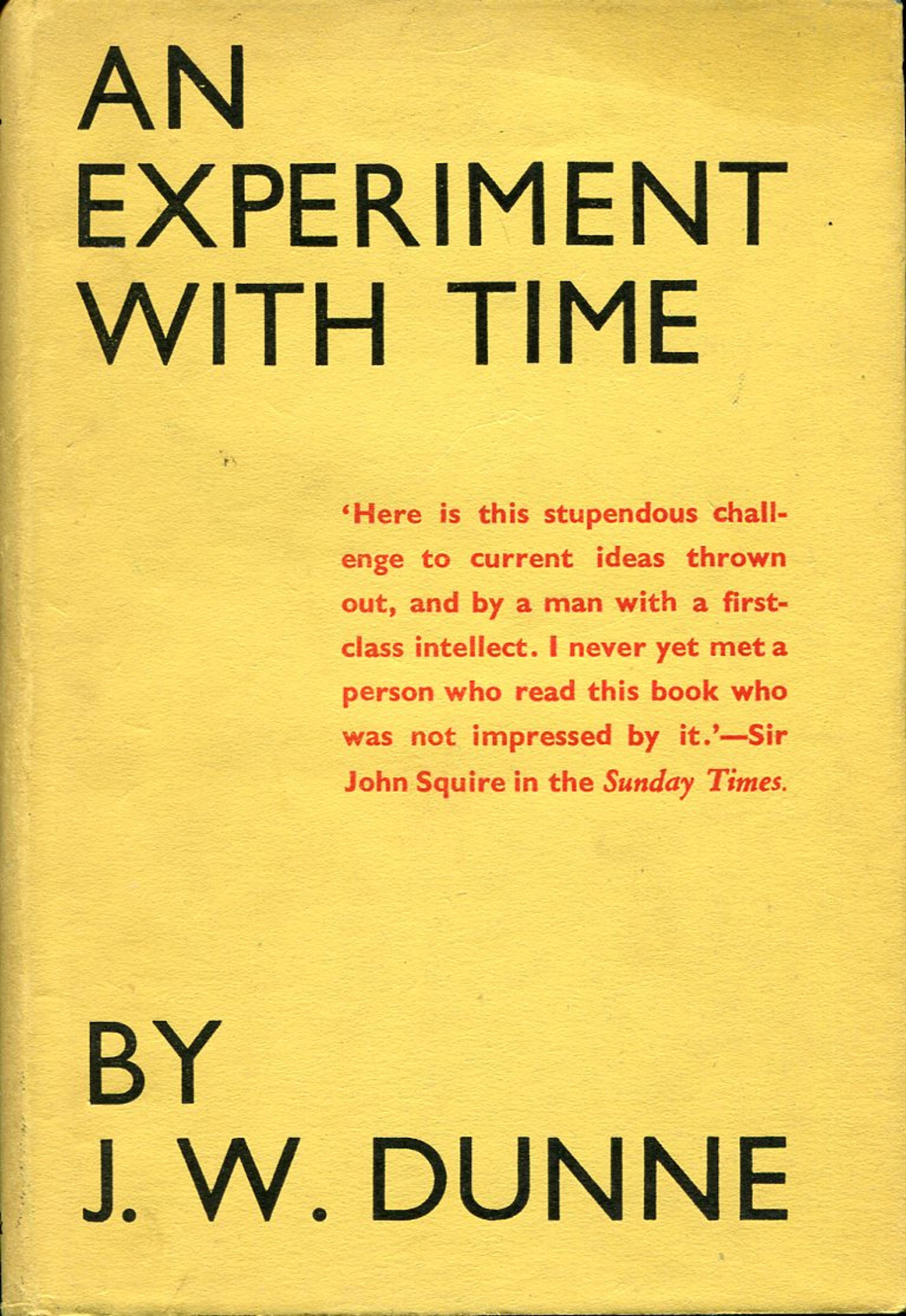

In 1927, John William Dunne (1875-1949), an aeronautical engineer from Ireland, published a book called An Experiment with Time. The book had three aims. The first was to provide a list of precognitive dreams that Dunne himself had had. The second was to offer a manual describing how one might train one’s mind to see into the future while dreaming. According to Dunne, with appropriate training, everyone could do this. The third aim was to provide a theory of time called ‘serialism’, which was intended to explain how precognitions might be possible.

An Experiment with Time (1927) by J W Dunne. Public domain

Serialism begins with the premise that anything that moves must move in time. For example, a car moving on a road is in one place at t1, and at another place further up the road at t2. If there was no time, it would be hard to describe the car as ‘moving’ at all. But, Dunne argued, time itself moves. It would be strange to say that time does not move. It cannot stand still. (The British philosopher Antony Flew noted that Dunne does not distinguish straightforward spatial motion from the elusive ‘flow’ of time, which is the main blunder that eventually leads to his bizarre theory of time.) So, Dunne thought, there must be a meta-time or hypertime, a higher series of ‘time above time’ describing the movement of the time we inhabit. But this ‘time above time’ must also move (otherwise it would not be time). So, there must be a third series of time, and so on to infinity. Dunne believed that, when we dream, our minds can gain access to these higher series of times, some of which contain future events.

The book became a bestseller. It was republished in several editions and influenced several key 20th-century writers, including Jorge Luis Borges, C S Lewis, J B Priestley and J R R Tolkien. The physicist Arthur Eddington wrote an approving letter to Dunne, which was published in later editions of the book. The wider public became fascinated with the idea of ‘seeing the future’, to the point where the phrase ‘Dunne dream’ became a shorthand for any precognitive dream.

Broad got rid of the idea that time itself must move through time

By contrast, the book was ridiculed in academic circles. Not so much because Dunne believed in precognitive dreams (as a matter of fact, many academics thought that the catalogue he provided of these dreams was the only valuable thing about his book), but because of his bizarre theory of time. One reviewer in The Journal of Philosophy said that it was very hard to take it seriously, another in Nature considered the possibility that the book was just a practical joke, and an unimpressed philosopher called serialism a ‘logical extravaganza’.

Broad was the only professional philosopher to seriously engage with Dunne. Trinity College holds Broad’s own copies of Dunne’s books, whose margins are covered in extensive notes containing suggestions for fixing serialism and using it to generate a philosophically robust explanation of precognitions. He even published a stand-alone paper on Dunne in the journal Philosophy in 1935, and Dunne features in several places of his magnum opus, Examination of McTaggart’s Philosophy (1933-8).

Broad addressed what might be called the ontological problem with precognitions. In the first half of the 20th century, one of the most widely accepted views of time was the ‘growing block’ theory, which says that the past exists, the present exists, but the future does not. This accords pretty well with our everyday intuitions about time, but poses a particular philosophical problem for the existence of precognitions. Say I foresee, in a dream, what happens next Saturday. Supposing the growing-block theory is true, next Saturday does not (yet) exist. So, what was it that I saw in the dream? How could I have seen something that does not exist?

The engagement with Dunne motivated Broad to propose one of the first ‘hypertime’ theories. This is a group of theories that claim that time has two (or more) dimensions, similar to the way that the space we inhabit is three-dimensional. In Broad’s view, one dimension had a growing-block structure. In this dimension, the future does not exist. But, he suggested, there could also be a second dimension of time in which the future does exist, and so contains the foreseen event. In a precognitive dream, we gain access to it. This is a streamlining of Dunne’s logical extravaganza: Broad got rid of the idea that time itself must move through time, and ditched the ‘infinite’ series of dimensions. Two dimensions are enough.

While Broad attempted to make Dunne’s theory less logically extravagant, one of his students at Trinity took the application of logic to psychical research to a much higher level. Casimir Lewy (1919-91) was one of the 20th century’s great philosophers of logic. He influenced an entire generation of analytic philosophers, and the philosophy faculty library at the University of Cambridge is named after him. There is no evidence that Lewy was interested in spiritualism during his undergraduate studies (during which he was already publishing in the journal Analysis). But this seems to have changed in 1938.

During the summer of 1938, before starting the final year of his undergraduate studies, Lewy, then 19 years old, visited the Polish painter Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (more commonly known as Witkacy) in his studio in Zakopane, Poland, to have a portrait painted by him. Witkacy was well known for his interest in mysticism and spiritualism. He attended séances, and many of his paintings were done under the influence of psychedelics. Witkacy’s pastel drawing of Casimir from that summer is currently in Trinity College, and accompanies many online resources about him, including the Wikipedia article. We do not know what exactly happened during Lewy’s sitting for Witkacy. But, a year later, Lewy took an unexpected decision, and started to write his doctoral dissertation on psychical research.

Portrait of Casimir Lewy (1937) by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz. Courtesy Wikipedia

The dissertation, entitled ‘Some Philosophical Considerations About the Survival of Death’, was supervised by the British philosophers John Wisdom and G E Moore, submitted in October 1942, and examined by Broad and Cecil Alec Mace, a psychologist who, five years earlier, gave the F W H Myers memorial lecture at the Society for Psychical Research. The dissertation marked the arrival of a new methodology in philosophical engagements with psychical research. By the time Lewy was writing his dissertation, linguistic analysis had taken over. Cambridge philosophers were now interested in the meaning of words and propositions, and in the role that empirical data can play in the metaphysics of truth. The first sentence of Lewy’s dissertation is exemplary of this new approach: ‘Is the statement that I shall survive the death of my body meaningful?’

In the course of the dissertation, Lewy applies linguistic analysis to two competing theories about ghosts. The first theory was proposed by Broad in 1925, and became known as the ‘psychic factor’ hypothesis. Broad asks: ‘Might not what we know as “mind” be a compound of two factors, neither of which separately has the characteristic properties of a mind, just as salt is a compound of two substances, neither of which by itself has the characteristic properties of salt?’ The idea is that the ‘psychic factor’ can, under certain conditions, survive the bodily death of the physical factor, and perhaps manifest itself as a ghost.

By the time the papers got to publication, they had had all the references to psychical research redacted

Lewy found the theory unconvincing. He thought that the key things missing from Broad’s theory were verifiability criteria. Verification was a popular theory of meaning, expressing the idea that a statement was meaningful if and only if it could be verified. For example, the statement ‘there is an apple on the table’ is meaningful because I know how it could be verified: I can go and see whether an apple is there. By contrast, many thought that highly metaphysical or religious statements like ‘God is good’ were meaningless because we cannot imagine how we might be able to verify them. This, Lewy argued, is precisely the problem with Broad’s theory: how could I verify that only a part of me has survived bodily death? If I am to do the verifying, I have to exist as the same individual before and after the verification, not just one of my two ‘factors’.

The second theory that Lewy attacks came to be known as the ‘psychic ether’ hypothesis. This was suggested by H H Price, the Wykeham Professor of Logic at Oxford, now mostly known for his work on the philosophy of perception. Price, like Broad, was heavily involved in the activities of the Society for Psychical Research (which elected him president in 1939 and 1960). He attended parapsychological conferences in the 1950s and, on one occasion, took mescaline, curious to see whether it would give him paranormal powers. (It didn’t.)

Price claimed that the ‘psychic ether’ was ‘a something intermediate between mind and matter … something which is in some sense material because it is extended in space … and yet has some of the properties commonly attributed to minds.’ Price believed that, once a particular mental image has come to exist (eg, if you look at an apple, the image comes to exist in your mind), it might perhaps continue to exist in the psychic ether even after the death of the mind that produced it. Under certain conditions, a bundle of these surviving images can become visible as a ghost to a medium or a particularly sensitive person.

Lewy demurred, arguing:

To say of any particular image which I have at a given time t that it, that particular image, exists at t, is to say that I have it at t; and to say of any particular image which I had at a given time t1 that it, that particular image existed at t1, is to say that I had it at t1 … Thus it is logically impossible that an image which I have at a given time should continue to exist after I have ceased to have it. A fortiori it cannot continue to exist after my death.

In other words, images are intrinsically tied to the times at which they are had and the acts of having them. They cannot exist on their own past those times and past those acts.

What is interesting about Lewy’s critique is that he thought that the falsity of Broad’s and Price’s theories could be shown purely by attending to logic and language alone. No need to attend séances, measure vibrations emanating from the brain, or put mediums into parapsychology labs. Just by thinking about the meaning of the words (‘psychic factor’ and ‘image’) used to articulate the theories, we can show that they are deficient.

Despite the failings of Broad’s and Price’s ghost theories, Lewy surprisingly concluded that the statement ‘I shall survive the death of my body’ might be meaningful, under certain very specific conditions, and with a very specific use of language. While this might seem like a very cautious conclusion in a marginal discussion about an obscure topic, for Broad and early career Lewy, psychical research was not just an extravagant hobby. It actively shaped their ‘official’ philosophical views. As we already saw, Broad’s philosophy of time in his Examination of McTaggart’s Philosophy was heavily moulded by the need to accommodate precognitions. The discussion of the ‘psychic factor’ is nested in the core of his influential book The Mind and Its Place in Nature (1925). His views about ‘basic limiting principles’ of reality were shaped by the worry that they might be violated by psychical phenomena. These included violations of the laws of physics, or the implications of new forms of direct mind-to-mind communication without the need for physical intermediaries like ears, mouth or air. Similarly, Lewy’s dissertation formed the basis of his two key papers published in Mind and Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society soon after his viva voce examination.

What is curious about these two papers, however, is that, by the time they got to publication, they had had all the references to psychical research redacted. The spooky stuff has been sanitised away. This is not surprising. We know from Lewy’s correspondence with Broad and Moore that, by the time he got to the end of his doctorate, he was (unlike Broad and Price, both of whom held professorial chairs at this point) desperately trying to land an academic appointment. Associating himself with psychical research, which even Broad, at one point, described as a ‘spooky’ discipline, might have been too risky.

Many of these philosophical engagements with parapsychology and psychical research have now been forgotten – or perhaps brushed under the carpet out of embarrassment. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, for example, only contains a few words about Broad and Price’s interest in parapsychology, and my own forthcoming paper is currently the only one on Lewy’s work on psychical research.

Some of Broad and Price’s contemporaries also thought that psychical research was not worth any attention by historians of philosophy. Rudolf Metz’s tome A Hundred Years of British Philosophy (1938) contains a mere two pages on psychical ‘researchers’ (the quotation marks are his) and their ‘voluminous writings’. His tone is dismissive, and he says that ‘it hardly redounds to the credit of modern British philosophy that so many thinkers and investigators who have otherwise to be taken seriously have on this ground proved so over-venturesome.’

Despite Metz’s dismissal, many philosophers continued working on questions in psychical research long into the 1950s and ’60s, after psychical research had left other departments in the modern university. These philosophers included Antony Flew, Martha Kneale and other overlooked thinkers such as C T K Chari, H A C Dobbs and Clement Mundle. It also appears that Kurt Gödel believed in the afterlife.

Cambridge was one of the birthplaces of analytic philosophy, which prides itself on dispensing with speculative metaphysics, and putting a heavy emphasis on scientific precision and empiricism. But ‘spooky’ topics like telepathy, after-death survival and ghosts permeated the philosophical ecosystem in Cambridge and beyond long into the 1960s. It pushed many of the thinkers interested in it towards new and creative explorations of the nature of time, matter and language. So, when Alan Turing, one of Cambridge’s most famous alumni, turned his attention to artificial intelligence and made his era-defining contribution, it was natural that he would be concerned about a problem many of his peers considered deeply puzzling: telepathy.