Do you recall the first time you knew you would die? It’s a milestone, realising your time is limited. That things happened before you, and will happen afterward, in your absence.

As we grow up, the understanding of death comes in stages, but it culminates in acknowledgment of one’s own – unavoidable yet unpredictable – mortality. Sometime between the ages of six and 10, children become aware that their time is inescapably bounded.

Roughly the same might be said of humanity’s self-knowledge. Only recently has the human collective begun accepting the fact it is itself mortal. We now appreciate that events unfolded for aeons before us and that our species can disappear, never to return. One day, the cosmos will persist without human witness, nor any inherent tendency to manifest things we cherish.

The anti-war campaigner Jonathan Schell called this realisation the ‘second death’. Growing up, each of us comes to terms, psychologically, with a ‘first death’ – our own – but, beyond this, lurks the realisation that humankind itself hasn’t always existed and won’t be around forever.

For most of history, such understanding was lacking. People could defang – or outright deny – the possibility of beginnings and ends greater than those of our own biographies by appealing to eternity. Before we found evidence to prove otherwise, it was permissible to presume that, beyond tangible scales, time has no true bounds. For millennia, people have found comfort in this, because nothing dies in eternity. Given eternal time, every possibility – no matter how wildly improbable – will repeat and recur limitlessly. Outside our island of perceptible time – within eternity’s boundless ocean – it remained plausible to assume that all deceased things will eventually resurrect.

It’s now clear humanity lacks the luxury of eternity. We know this because evidence has accumulated to show that there are greater, even more encompassing mortalities than our own. We now understand Earth and its life had their origins and, one day, they will be cremated by our ageing Sun. A ‘third death’, then. Beyond that, even the Universe itself has its bounds: it began with a bang, and the consensus view is that, in the distant future, it will likely have its end. Thus, a ‘fourth death’. Multiple grander mortalities, expanding concentrically outward.

We are only just coming to terms with this – this supremacy of finitude. It marks a historic reorganisation of our sense of orientation that may, one day, be judged comparable to that of the Copernican Revolution. Just under 500 years ago, Nicolaus Copernicus initiated a string of discoveries eventually proving our planet is not the centre of a tidy, manageable cosmos. Instead, Earth pirouettes around a mediocre star within an ungraspably vast Universe. It took generations for people to start noticing – and giving names to – what Copernicus had wrought. Similarly, we are only now waking up to the significance of the nested mortalities we live within. With the most seismic revolutions, it takes time for the dust to settle before we can glimpse the landscape transformed.

However, whereas Copernicus made us feel insignificant in space, placing bookends on time stands set to reverse this, by insinuating that our acts might just be more cosmically resonant than we previously dared presume. One revolution, undone by another.

Why? I argue that abandoning eternity is ultimately galvanising: for it implies that what we do in our moment on Earth genuinely matters beyond our own fleeting lives. Only by finding time’s cosmic bookends has modern science thrown into crisp relief the truth that what happens next might resonate indelibly. Because, if time has extremities, then history will never repeat; and if what’s happening here and now will never reoccur, certain decisions can never be taken back or reversed.

Historically speaking, when people have encountered something whose edges they cannot directly see, they have tended – ahead of contrary evidence – to assume it simply lacks limits. Staggered by size into stupor, we tend to conflate extremely large things with limitless things. It proved no different with time, beyond perceptible scales. For much of human history, what terra incognita was for geography, eternity was for chronology. It was the amorphous unknown lurking beyond what was concretely measured.

While the Abrahamic religions may have appeared to place boundaries on time millennia ago – with their teachings of genesis and apocalypse – eternity nonetheless saturates these creeds. Worldly time was conceived of as but a brief hiatus, environed by two eternities: a vanishing, Biblical ‘vale of tears’ cleft between the boundless precedent of an uncreated divinity and, afterward, the unending afterlife promised for the souls He created.

Perhaps one reason why the idea of eternity has persisted for so long is that it offers consolation. In infinite time, all possibilities inevitably cycle without limit, such that unprecedented change and irrecuperable loss evaporate. The only trajectory is an orbit. Everything gained is eventually lost; everything lost, eventually regained.

However, it’s also the case that the evidence required to banish eternity has accumulated only gradually. Because knowledge is tethered to observation, we know only so far as we – or our tools – can see. Thus, before humans invented clever ways to survey scales greater than the immediate, it was impossible to disqualify hunches that – beyond the purview of what’s humanly tangible – time lacks proportion and eternity reigns.

Because imagination fails to circumscribe such aeons, it’s easy to assume they lack circumference entirely

People speak of the ‘god of the gaps’, alluding to how the supernatural slowly recedes as we learn more about the cosmos around us. Something similar has happened with eternal time. As we’ve probed and pried farther, we’ve revealed beginnings – and possible ends – for Earth, life and the Universe, replacing eternity with finite timescales at increasingly encompassing scales. Yet, with each advance, eternity has merely ceded ground, retreating into the darkness outside the flame lit by our knowledge.

Even in the present day, it’s often forgotten that the unthinkably vast durations revealed by modern science – described by the term ‘deep time’ – are distinct from eternities. Because imagination fails to circumscribe such aeons, it’s easy to assume they lack circumference entirely.

If accepting such immense finitudes is difficult now, it would have been unthinkable earlier in human history, before radio telescopes and radiocarbon dating. A millennium ago, it would have been evident human lives are not eternal. However, based on available evidence, it would have remained underdetermined as to whether, beyond this familiar span, things don’t just boundlessly cycle and repeat.

This mattered because it influenced how people behaved. If events inevitably reset, regardless of what happens in the present, everything accomplished now will eventually wash away. Assuming this, the Roman statesman Cicero concluded there was little point attempting to impart legacies that are ‘durable’, much less ones that are indelible.

Before an archaeological record was compiled, cross-referenced and communicated across continents – rather than remaining constrained within one – it wasn’t possible to falsify hunches that human history has been cycling on Earth, forever, without definitively beginning or drastically changing.

We envision a time before which no humans practised farming or writing, and a time after which some started

Similarly, before the globe had been fully mapped, people could plausibly believe that everything locally chronicled and accomplished had already taken place – and would later ceaselessly repeat – on other, uncontacted landmasses.

In Leviathan (1651), Thomas Hobbes spoke of the shift from a warring ‘state of nature’ to that of the ‘social contract’. This might now sound like what we understand as the transition from prehistory to history. We envision a time before which no humans, anywhere, practised farming or writing, and a time after which some started. But this wasn’t what Hobbes had in mind. He clarified that he believed the precivilisational state ‘was never generally so, over all the world’.

For Hobbes, global history represents a revolving, never a rupture. Regions might slither between various situations, but, from the planet’s perspective, these will all have already been manifested elsewhere. Assuming this, humankind’s collective future cannot come to look different from its extended past.

Hobbes’s contemporaries – from Francis Bacon to Edmond Halley – remarked that, though new things appeared to be being invented, they couldn’t disprove a lingering suspicion all these feats hadn’t already been innumerably achieved before – by forgotten civilisations, throughout time immemorial. Eternity resided over the horizon, in undiscovered lands.

In the 18th century, these perspectives began to change – but not without a fight.

Throughout the 1700s, naturalists began looking to Earth to answer the question of the present’s location in time. Geology had begun consolidating as a science. Ahead of digging into the planet, the first geologists assumed they might find proof of nothing really changing throughout Earth’s history. They expected remains of everything currently alive on the surface to be located even in the deepest strata. Some predicted that, if we dug to Earth’s core, we would find human remains.

When scientists began peeling Earth open, revealing the fossil record’s testimony, this isn’t what they found. Not only did the eldest strata entirely lack organic remains, they also noticed the skeletons changed drastically – becoming less familiar – the further back in time they looked. No one could find fossilised humans in the older strata, which suggested creatures like us were embarrassingly recent additions. (There was one false positive, but that turned out to be a giant salamander’s skeleton.)

Homo diluvii testis: a fossil of a giant salamander found in a limestone quarry in Öhningen, Germany, and, in 1726, believed to be the spine and pelvis of a child who had been trampled during the Biblical flood. Courtesy BnF, Paris

The time was ripe for the first physical theory comprehensively predicting both the past and the future of the Earth system. This came from the French polymath Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon in the 1770s. He conjectured our planet was irreversibly losing an original and finite fund of internal heat. A molten birth, hurtling inexorably to frozen death.

Retreating to his basement forge in Burgundy, Buffon heated iron balls then measured their cooldown times, before scaling them up to the globe’s size. From this, he estimated Earth was around 74,832 years old; that life emerged upon it 35,983 years ago; and that it would remain habitable for another 93,291 years. (Rounding wasn’t yet scientific convention.) Nonetheless, eternity wouldn’t depart without a struggle. Proof was building that Earth was far older and, with time’s limits seemingly bursting, some saw evidence of limitlessness.

Hutton insisted the past and future of the Earth system was not just enormously long but limitlessly long

Not long after Buffon’s investigations, the Scottish geologist James Hutton argued that, in explaining Earth’s features, only currently observable causes should be conscripted. Overapplying this rule, he became convinced our planet had never looked drastically different from how it looks today, nor could it change in future. This inspired his declaration that geologists find ‘no vestige of a beginning, – no prospect of an end.’ He even questioned evidence there had been a time when our planet entirely lacked life, insisting the Earth system never undergoes unprecedented changes.

Bewitched by the aeons required to sculpt vast mountains using only mundane processes – like erosion or sedimentation, which work at a piecemeal pace – Hutton insisted the past and future of the Earth system was not just enormously long but, instead, limitlessly long. Sometimes hailed as the ‘discoverer of deep time’, this is misleading. Hutton was drunk on boundlessness – which is shallow because, in eternity, nothing truly changes – not meaningful depth.

This way, eternity briefly recurred: by receding into the mists of geological time. But, despite Hutton’s efforts, Buffon’s view – that Earth’s biography has determinate bookends in time – slowly won the day. Of course, Buffon’s methods were rudimentary, the results false, but it was an important start. His experiments – attempting to simulate Earth’s evolution in miniature – provide the common ancestor of today’s sophisticated climate models.

Ultimately, Buffon’s search for our planet’s biographical bookends provided the extremities within which life’s story could begin to be understood as unfolding – and in a way that could admit genuine firsts and irreversible losses.

No longer was it possible to hold that everything humanly or biologically possible has already occurred, given a boundless past. This way, bookending the past liberated the future. Hope for entirely new things – never before achieved, anywhere – could take hold.

The same, however, applied for global challenges entirely unprecedented: including disasters, more destructive than any previously recorded.

In 1777, Buffon asked himself what would happen if all organisms on Earth were instantaneously annihilated by some disaster. To his mind, life would spontaneously reappear, briskly repopulating the planet with, he assumed, the same species as before.

Though the biography of Earth had been granted its bookends, the same hadn’t yet been confirmed for its myriad species. Planets were inchoately understood as things with a definite birth, a bounded lifespan and a foreseeable death; but it wasn’t yet definitively accepted that species also experience such milestones.

There wasn’t yet consensus on how species originate, so there couldn’t yet be conclusive grasp that, once lost, they are gone forever. In the earlier 1800s, naturalists continued to imagine that complex creatures could simply pop into existence without forebears. Hutton’s followers imagined dinosaurs one day, spontaneously, returning. Others theorised that the first humans were generated, effortlessly, from sea slime: no parents necessary.

Darwin proved we were all born of time, not slime

Charles Darwin changed this. After On the Origin of Species (1859), it became undeniable that nature cannot generate complicated creatures from scratch. The existence of us, today, required the precedent of countless yesterdays: building laboriously from simpler into less simple ancestors.

This confirmed why members of the same species cannot spawn anywhere, anytime, effortlessly, without connection to countless parents and precursors stretching back, uninterrupted, to life’s beginning. Darwin proved we were all born of time, not slime. Crucially, this also established why, if every member of a species is destroyed, that lifeform isn’t returning anywhere, ever again.

This way, Darwin proved that species, too, have bookended biographies – that they are born, persist, and perish – and that their stories unfold firmly within the horizon of consequential action. Deeds and decisions in the present can extinguish them, which leaves an indelible mark on Earth’s future, because they won’t ever be returning.

The idea of eternity clung on elsewhere though, beyond Earth, as our awareness of the voluminousness of the cosmos grew. In the wake of the Copernican Revolution, other planets became the arena wherein expectations of endless recurrence, and thus immortality, could be transposed.

After astronomy revealed our planet is but one among uncountably many, it made people feel small. But it didn’t initially make them feel lonely. Far from it. Responding to the cosmic vastitudes revealed throughout the 1600s, Blaise Pascal admitted that the ‘eternal silence of these infinite spaces terrifies me’. But people forget what else he said: what terrified him wasn’t the prospect we were alone, but the opposite. He hated the ignominy of being unnoteworthy, or the idea of countless populated globes that ‘know nothing of us’. Because Pascal assumed all worlds host the same animals Earth houses – down to the ‘mites’ – such that all Earthly things must cosmically recur ‘without end and without cessation’. What alarmed him was how mundane this extramundane churn of living globes makes us.

Pascal was far from alone. Confronted by a Universe far larger than had previously been permitted by limited imaginations, people simply assumed it lacked limits entirely. Contemporaries, like the theologian Henry More, concluded that there will be ‘endless’ Earths and humankinds. Dizzyingly, he pictured infinite Adams coupling with innumerable Eves. Nothing in infinity is unique, nothing mortal.

Initially, Copernicus’s revolution didn’t shrink humanity’s ego. It inflated it to cosmic catchments. And these assumptions would last, undefeated, until at least the early 20th century.

Consider the words of Arnold Taylor, a reverend of a leafy English village, who in 1901 posted a letter to the editors of a science magazine, seeking consolation. Taylor had been spooked reading a book claiming there might not be humans on other planets. Such a statement, our reverend felt, was surely too ‘sweeping’?

A century ago, many assumed the inhabitants of other planets would be humans

Troubled, Taylor asked what astronomers – or, as he had it, ‘the planetoscopists’ – thought on the matter. Taking Mars as an example, he said he assumed the consensus was that it was ‘probable that human beings may be living there’.

When it came to ‘planetoscopy’, Taylor had familial skin in the game. Decades earlier, his great-uncle W R Dawes had drawn the first detailed maps of Mars: highlighting what he mistook for waterways. This was taken as confirmation our neighbouring planet was inhabited.

This wasn’t an isolated view. A century ago, many like Taylor assumed the inhabitants of other planets would be humans; that everything happening here was also going on over there.

By this time, time’s bookends had expanded to subsume the entire solar system. Thanks to thermodynamics, it was now scientifically accepted that our Sun would one day definitively die, erasing the possibility of living worlds pirouetting around it. But what of systems beyond? Though stars might experience bookended biographies – ageing and dying – the Universe containing them was not thought to suffer such inconveniences. It was largely assumed that the cosmos, at large, was limitless and ageless.

Accordingly, even though Darwin’s theory made it wildly improbable, people could still seek immortality for our species in the stars. Given an eternity of chances, even the most unlikely confluence of conditions will innumerably repeat. Hence, why, in the 1929 words of Robert A Millikan, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist, there will always be, somewhere, an Earth – ‘it matters not which’ – whereupon ‘some billion years hence the development of man still may be going on.’

Lemaître theorised the Universe was birthed by titanic detonation

In an eternal, infinite universe, such resurrection is inevitable. Even Darwin himself once alluded, furtively, to an evolutionary ‘fresh start’ following our Sun’s death. Such a thought was comforting, some began remarking, given that humans had begun messing with atoms.

But then the Universe itself started gaining bookends in time. Peering into the world’s largest telescope, throughout the 1920s, Edwin Hubble noticed something bemusing about other galaxies outside our Milky Way. They are rapidly flinging away from us. Our Universe is expanding.

Extrapolating backwards, this implied an explosive beginning. Inferring forwards, it implied a rarefied end, with matter and energy eventually centrifuging into nihility. The Universe – as one giant physical whole – was gaining a beginning and an end.

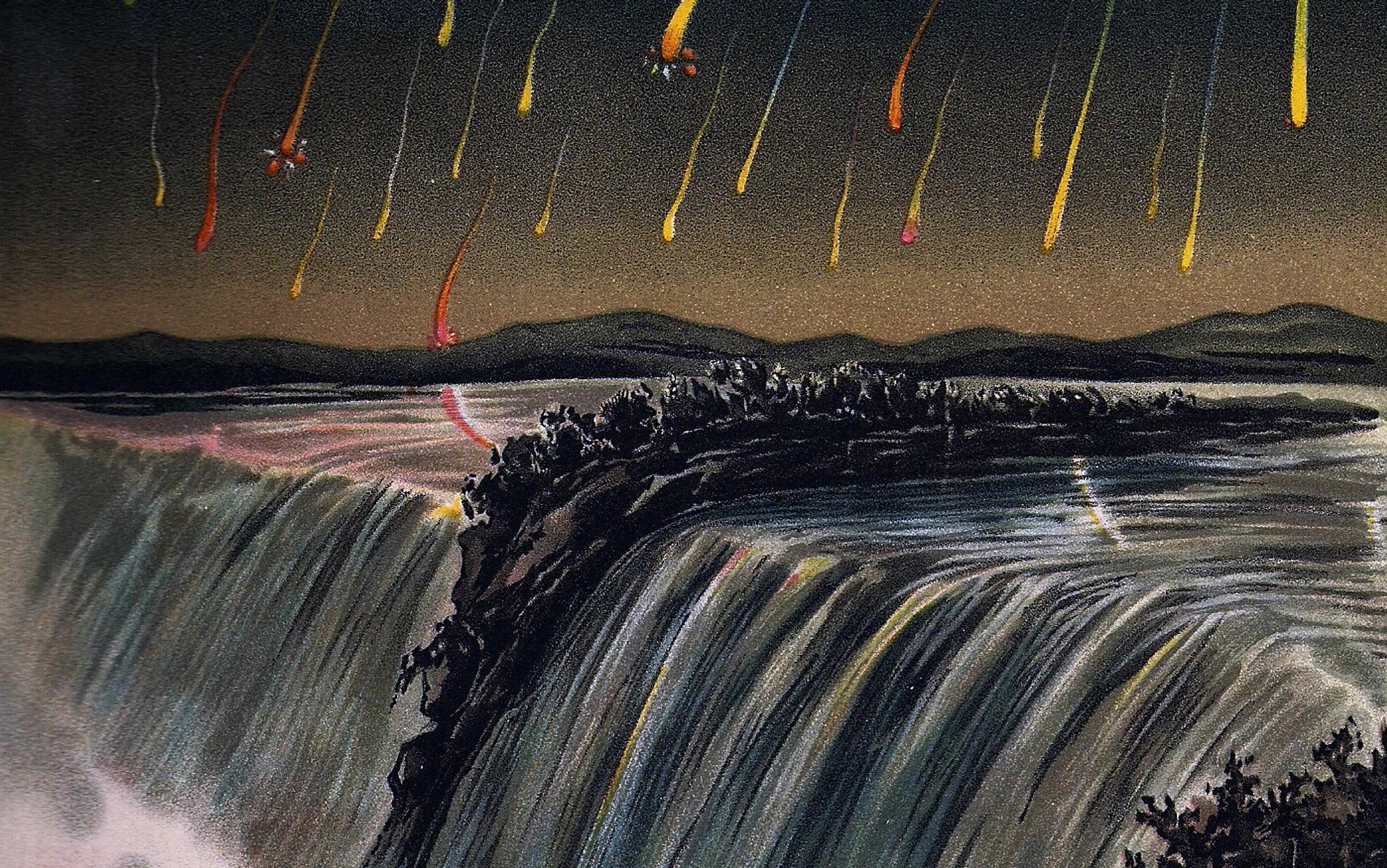

The Belgian physicist Georges Lemaître pieced it all together first. He theorised the Universe was birthed by titanic detonation. In 1931, Lemaître proposed our cosmos isn’t unborn and undying, but can be compared to a fireworks display. Standing on a ‘well-chilled cinder’, we peer into space, witnessing the explosion’s ember-scattering aftermath.

In 1946, Lemaître published a book summarising his vision. Just three years later, speaking on BBC Radio, the astronomer Fred Hoyle absentmindedly referred to Lemaître’s theory as the ‘Big Bang’. The name stuck.

From 1948 onward, Hoyle himself launched a counterstrike against this bookending of universal chronology. Like Hutton before him, he tried to defend eternity from time’s creeping encroach – albeit now at cosmological, rather than geophysical, scales. Hoyle sought theories that could explain cosmic expansion without postulating cosmic beginnings. But the Big Bang, eventually, started winning the day.

This had profound ramifications. Previously, in an eternal Universe, it was possible to assume that life had never begun, but simply circulates – and always has done – from system to system. Earlier generations of scientists speculated about ‘astroplankton’, or ‘space-spores’, which could accomplish this job of spreading life unceasingly.

This allowed conjecture that ‘organic beings are eternal like matter itself’. It also meant people could find comfort in claims that all life, throughout the Universe, is ‘related’: one circulating, immortal family; not isolated, unrelated refugees. What’s more, if you hold that life never properly began, it’s hard to imagine it ever ending. Something that’s everywhere, everywhen, is impossible to exterminate.

We must confront the possibility that life began and is thus a fragile thing

The notion of an eternal Universe had long underwritten recurrent hopes that our own species, regardless of improbability, would reoccur. Hence, why, as speculators had previously assuaged, the stars are ‘future regions of our immortality’: where there will always be ‘other suns, other earths, other humanities’; our ‘successors’ in mind’s ‘universal and eternal history’.

The discovery that the Universe itself appears to have bookends obliterated this. Noticing this in 1953, the anthropologist Loren Eiseley spelled it out. The old ‘idea of an eternal universe’, he wrote, allowed ‘an infinity of time in which man might arise again and again’. This provided assurance (or, better, insurance).

Yet, Eiseley realised, building evidence for the Big Bang demolishes such hope. No longer can we assume that life eternally circulates: drifting as ‘spores’ from ‘the wreckage of burned-out systems to systems beginning anew’. We must confront the possibility that it began and is thus a fragile thing: with more or less of a foothold in existence, depending on how widely distributed it is.

The Russian-born American cosmologist George Gamow concurred. In 1941, he announced that the Big Bang means the problem of life’s definite origin ‘has to be faced anew’. There was a time when the cosmos had no life in it, anywhere, and a time after which it did. This way, biology – as a cosmic phenomenon – became a biographical, bookending thing too. It is something that emerged and must eventually die out. Conclusions from thermodynamics continued to support this. One very distant day, our cosmos will spend all its useful energy, making complex life impossible, everywhere.

The Big Bang provoked even more disquieting questions. As Enrico Fermi asked in 1950: ‘Where, then, is everybody?’ He was talking about aliens. Previously, it was possible to assume interstellar journeys were impossible. If the Universe was eternal, we would already have been visited.

But suddenly it became permissible instead to conjecture we live in the cosmic epoch before which life, of whatsoever sort, has spilled outward: flooding throughout the firmament. Eiseley pointed this out, noting it now seemed ‘there has not been a sufficient period for all things to occur even behind the star shoals of the outer galaxies’.

Once again, bookending the past opened radical possibilities for the future. For Buffon’s generation, this unfolded at planetary scale; now it was unfolding at cosmological scale. It became at least plausible to propose that the Universe’s future might look unrecognisably different from its past and present. Might biology be the spark that inflicts the change?

The evolution of brains like ours, on Earth, can hardly be assumed to be an inevitability

Humans were, at this time, themselves making strides towards building rockets. From this, further conundrums bubbled forth. Are we the first to have thought about hurling spaceships at other stars, and are thus radically alone in an otherwise insensate cosmos? Or, have countless others tried and failed? Indeed, atoms and rockets can lead to global suicide as well as interstellar emigration.

Launched in the 1960s to answer these riddles, the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) has since found nothing; only cosmic silence. What’s more, as the second millennium shaded into the third, numerous discoveries have confirmed the evolution of brains like ours, on Earth, can hardly be assumed to be an inevitability. We are the offspring of chance: a fluke product of the ‘roulette wheels that are galaxies’, as Stanisław Lem put it.

Perhaps this explains why we can’t tune into any sidereal hubbub. Perhaps we are simply the first, improbable beings to pose the question: Could we be the first?

If Earth’s life is unlikely and unprecedented, its ruination could therefore be a loss for the wider cosmos itself. Without predecessors, who’s to say what we might be capable of ultimately? There’s no precedent to learn from, but also no prior indication of limits on what might yet be achieved.

Demonstrating that time has bookends took millennia of enquiry, but its implications are bedding in only now. It was only by discovering that time is unfathomably deep – but not limitless – that our species has realised we don’t have the excuse or exculpation of eternity. There will be no reruns, no other Earths. Dying here means dying forever. And for all we know, there are no other intelligences in the Universe ready to take the baton. No longer can we rest assured, knowing that mishaps down here may be compensated by identical histories, elsewhere, throughout eternally churning star shoals. As Eiseley put it: ‘the same hands will never twice build the golden cities of this world’.

When we become aware of our own individual mortality – the ‘first death’ – we discover we have one, single opportunity with our own lives. We now must accept the same applies to life itself, cosmically speaking.

The yearning for immortality hasn’t left us, of course, but we now must look for it in Many-Worlds interpretations of quantum physics and other increasingly exotic, unreachable places. Where centuries ago, it was possible to hold that one’s history might repeat on other continents – and, later, on other planets – we now must seek the comforts of recurrence in parallel universes.

The degree to which we have banished eternity outward, from unexplored landmasses to the outskirts of spacetime, is the extent to which the stakes – of what unfolds here and now – have heightened.

If orienting ourselves in space generated the Copernican worldview, gaining our bearings in time is forging something new. The tenor of the former was mediocrity; the lesson of the latter is precarity.

It is the dying of the world that secures the immortality of our influence

What’s more, this new sense of our orientation – within time’s wider expanses – appears to have coalesced just in time. Up until recently, thinkers took deep time as indication of the present’s triviality. Within such magnitudes, ‘now’ seemingly shrinks to nullity, with its legacies being laundered away in the longer term.

But such a view is wrong. What’s currently unfolding might leave legacies that cannot be taken back, and were not inevitable, but still will be felt aeons hence. Time isn’t just deep; it’s deeply fragile. This dizzying knowledge needs, urgently, to sink in. Either we apply it now, just in time, and secure our future, or there might not be one. We don’t have the luxury of infinite retries.

Some may find it depressing to consider that, inevitably, everything dies. But they are missing one truth: it is only in a mortal world that consequences can resonate indelibly. After all, thermodynamics teaches that useful energy is finite in the Universe, and performing actions – of whatever sort – depletes this fund. Accordingly, the amount of actions that will ever get accomplished is finite, no matter how enormous this finitude might be. Selecting one action over any others possible, therefore, leaves an indelible cosmic legacy, regardless of how trifling. Because, though legacies can be reversed, this itself also expends effort, and energy isn’t infinite.

So, though the first lesson is that existence itself is bookended, the second – more profound – lesson is that this makes actions enduring in a newly cosmical sense. It is the dying of the world that secures the immortality of our influence.

This applies to modest goals as much as to hubristic, grandiose ones. We might call it the energetic imperative. Don’t let energy go to waste. Channel it towards what is beautiful, joyous, vivacious, ebullient! Because every moment we don’t, this ageing Universe forever becomes a less cacophonous, colourful place than it could otherwise have been.

Which is why this supremacy of finitude – this circumambience of grander mortalities than our own – is, in fact, galvanising. Just like the child coming to accept her ‘first death’, apprehending this might simply be part of growing up.

Ultimately, eternity intoxicates and stultifies, whereas finitude edifies by showing us that our decisions – right now – do matter. If immortality’s price is agency’s liquidation, I’d choose agency every time.