In 1936, Gary Cooper starred in the Oscar-winning film Mr Deeds Goes to Town and changed the meaning of marginal squiggles forever. Mr Deeds, a sweet man from small-town Vermont, survives the Great Depression juggling a string of quirky jobs – he’s a part-time greetings card poet, a tuba player, and an investor in the local animal fat factory – but then he inherits a cool $20 million from an estranged uncle. The film follows the travails of this loveable everyman as he attempts to give away his newfound wealth to the poor. Mr Deeds’s radical acts of altruism (for example, offering 2,000 10-acre farms to struggling Americans) quickly excites the ire of New York’s elite, not least the pernicious attorney John Cedar who plots to have Mr Deeds declared ‘insane’ by a New York judge.

In the film’s courtroom finale, various witnesses from his hometown attack Mr Deeds’s personality, claiming he has long been known as ‘pixillated’ – one of them clarifying:

Pixillated is an early American expression deriving from the word ‘pixies’, meaning elves. They would say, ‘The pixies have got him,’ as we nowadays would say a man is ‘balmy’.

Next, the snooty Dr Emile Von Haller (a parody of Central European intellectuals like Sigmund Freud) appears with a large graph depicting the mood swings of a manic depressive – pixillated affective errancies that map exactly onto the everyday eccentricities of Mr Deeds as described by other witnesses. Called upon to defend himself against such slander, Mr Deeds demonstrates his grip on rationality by celebrating his love of irrational things – from ‘walking in the rain without a hat’ to ‘playing the tuba’ during the Great Depression – before introducing the courtroom to a newfangled form: ‘the doodle’.

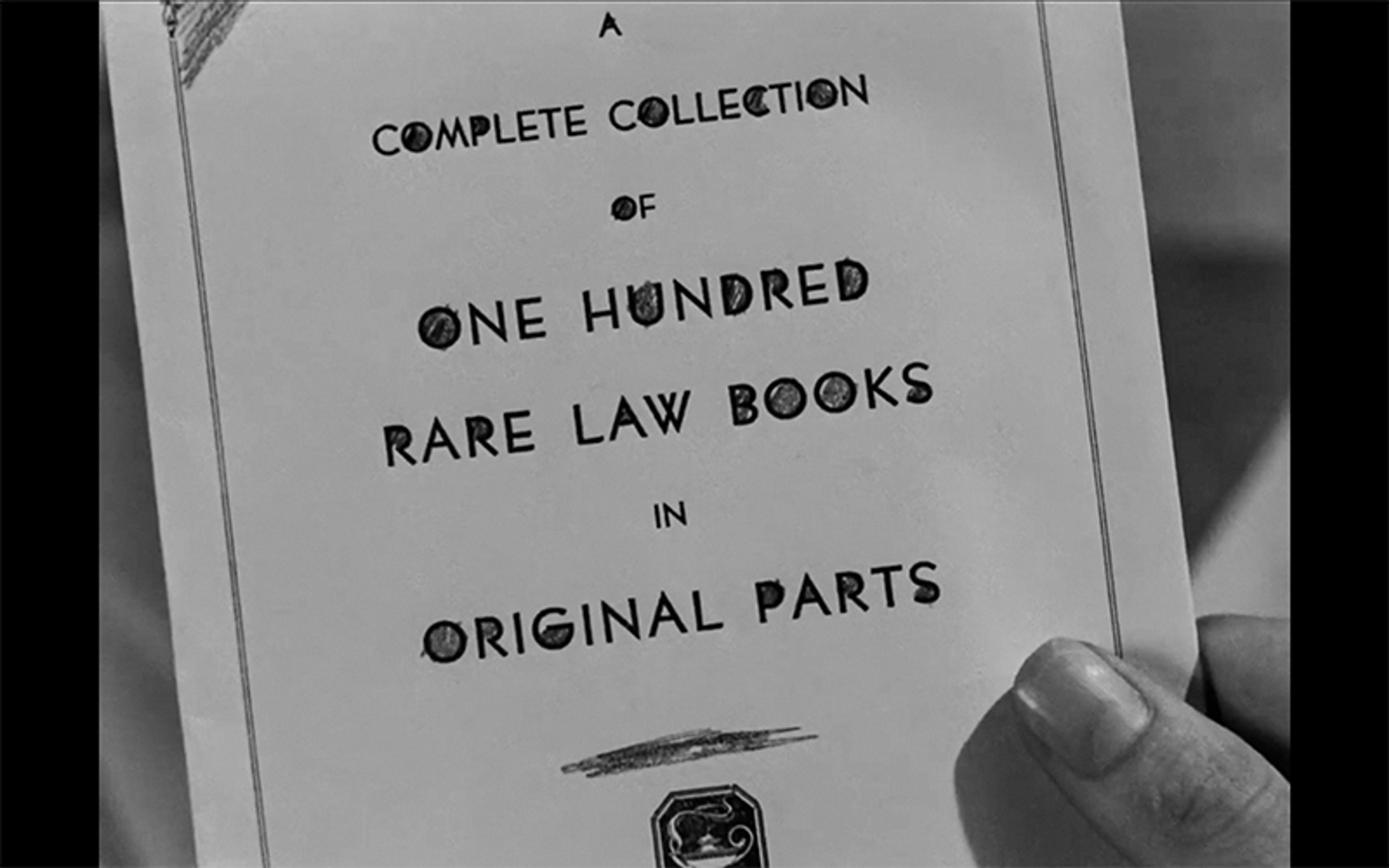

Stills from Mr Deeds Goes to Town (1936) directed by Frank Capra. Columbia Pictures

‘[E]verybody does something silly when they’re thinking,’ says Mr Deeds as the courtroom erupts with laughter. ‘For instance, the Judge here is an “O-filler”.’

‘A what?’ says the Judge.

‘An O-filler,’ says Mr Deeds. ‘You fill in all the spaces in the O’s, with your pencil … That may make you look a little crazy, Your Honour, … but I don’t see anything wrong ’cause that helps you to think. Other people,’ Mr Deeds says, ‘are doodlers.’

‘Doodlers?’ the judge exclaims.

‘That’s a name we made up back home for people who make foolish designs on paper when they’re thinking. It’s called doodling. Almost everybody’s a doodler … People draw the most idiotic pictures when they’re thinking. Dr Von Haller, here, could probably think of a long name for it because he doodles all the time.’

Reflecting the elitist psychoanalytical gaze back at Dr Von Haller, Mr Deeds finds something between ‘a chimpanzee’ and ‘Mr Cedar’ in Von Haller’s idiotic doodles, effortlessly exposing the hidden errancies that inform even the most rational analytical formulas.

The doodle is subversive. Democratically able to contain all gestures regardless of their formal difference. In light of this remarkable egalitarian power, the judge irreverently declares Mr Deeds ‘the sanest man that ever walked into this courtroom.’ Far from symbolising a frivolous eruption of nonsignifying noise, the doodle emerges in interwar modernist culture as a distinctly informal form oriented towards containing the value of apparently illogical things – like giving away your personal wealth for public good. Or upholding democratic processes that defend the rights of everyone (even the pixillated, meaning the ‘pixies’ rather than the ‘pixels’) in an age defined by the cold logic of mechanical reproduction, anti-humanist Taylorite efficiency programmes, and the global ascension of fascism.

As Mr Deeds says: ‘everybody’s a doodler’. Everybody matters.

To doodle is – if anything – a doddle. Equally the domain of avant-garde artists and incarcerated monkeys, presidents and poets, toddlers and self-help gurus, doodling is a radically non-hierarchical and non-classical activity that relays modernism’s epochal desire to reinvent traditional systems of value and to encourage the acceptance of new modes of being.

Doodles explode across modernist culture, high and low. From the constellatory squiggles and biomorphic shapes parading across Jean Dubuffet’s doodle cycle L’Hourloupe (1962-85) to Norman McLaren’s abstract expressionist cartoon Boogie-Doodle (1940), through to the ‘pixillated’ and ‘sagacious’ doodlers of, respectively, James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake (1939) and Samuel Beckett’s novel Watt (1953), the modernist exhibits a veritable will-to-doodle. But why does the doodle come to matter at this 20th-century modernist moment?

I would argue that the doodle is to modernism something like what the beautiful once was to the Renaissance: an aesthetic form that indicates a wider system of value intrinsic to a period of history. The beautiful embodies Renaissance ideals of harmony, rationality and humanism, just as the doodle alerts us to modernism’s fascination with difference and repetition, complexity, errancy and the ordered disorders that hide in irrational processes of all sorts.

The aesthetic experience of the doodle is never fixed, never singular

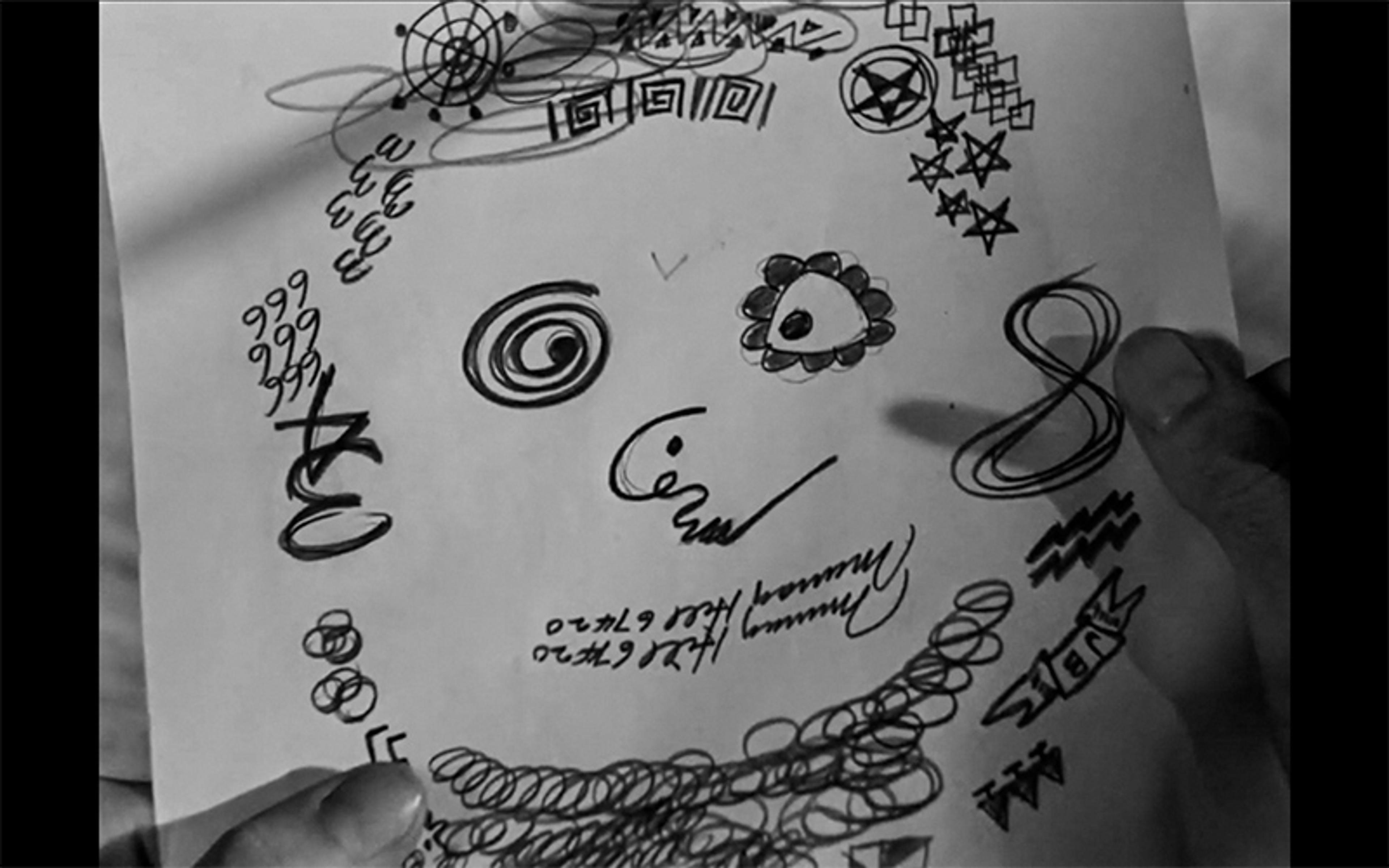

As a distinct aesthetic form, the doodle is often aligned with Paul Klee’s understanding that ‘A line is a dot that went for a walk’ – or as his fellow artist Saul Steinberg fondly misquotes it: ‘A line is a thought that went for a walk.’ Steinberg’s slippage points to modernist lines not being formally representative of things but things in and of themselves. This is form animated by the eventful idiosyncrasies of what the poet Henri Michaux calls ‘an entanglement, a drawing as it were desiring to withdraw into itself.’ Doodles are noisy and unfinished process-oriented forms – emerging always like a multitude of ‘starts that come out’, as the poet and musician Clark Coolidge says: they are minor gestural forces that open experience to novel possibilities of becoming. Doodles speak to the modernist idea of an endlessly wandering world, open, as the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy says, to ‘the indeterminate possibility of the possible’.

Page of doodles by Saul Steinberg, including a photocopy of a 1965 drawing. Saul Steinberg Papers, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, inv 3083 © The Saul Steinberg Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/Copyright Agency 2025

Because of its radical openness to difference, the doodle tends to function as a kind of meta-aesthetic attuned to containing a network of ambivalent affects and fleeting everyday aesthetic experiences that become increasingly common in the 20th century. Just as our consumerist lifeworld is a patchwork of ‘cool’ Nike ads, ‘cute’ outfits, ‘interesting’ data points, ‘dank’ memes and ‘whimsical’ shopping-mall muzak, the doodle presents scrawled assemblages that flitter with cute blobs, cool waveforms, interesting jottings and fey twinkling stars. The aesthetic experience of the doodle is never fixed, never singular.

Far from encouraging distinct sovereign aesthetic experiences like the beautiful, the modernist doodle presents a decentred experience that is, in part, about the meta-aesthetic expansion and reframing of classical aesthetic experience into something non-sovereign, multitudinous and relational. While drawing together errant, marginal and unworthy gestures long excluded from the royal aesthetic experiences favoured by the Renaissance, the doodle is about commingling weak and everyday forms in a democratic soup of bounteous difference and animate commixture.

Doodles have a long history, of course. There’s the ‘monkish pornographic doodle’ that the poet Lisa Robertson marvels at, drawn around a flaw in the vellum of a translation of the Codex Oblongus from De rerum natura held in the British Library. Or the variety of curious knots and flourishes that adorn the marginalia of Edward Cocker’s early modern ‘writing-books’ like Arts Glory (1669). Such pre-modern forms are largely treated as formless nothings before the modernist moment awakes to the informal value of doodled forms, whether avant-garde or popular. Indeed, the word ‘doodle’ enters popular parlance in the early 20th century – appearing alongside swaths of similar ‘doo-’ terms for worthless objects, errant movements and unbalanced states of mind, including ‘doodad’, ‘doodah’, ‘doolally’, ‘doohickey’, ‘doojigger’, ‘doo-doo’, ‘dooky’ and ‘doofus’ – as a variant both of old German words like Dödel (‘fool’) or Dudeltopf (‘simpleton’) and the loaded revolutionary war-era phrase ‘Yankee Doodle’ – before bursting forth across US pop culture with the success of Mr Deeds Goes to Town.

By the late 1930s, most major newspapers in the US take to clarifying the meaning of ‘doodles’, often alongside definitions of the promiscuous neurotic category of the ‘pixillated zany’, underlining the doodle’s comedy of psychoanalytical pretension. The Los Angeles Times in 1936 insists that ‘Persons who create geometric masterpieces during a telephone conversation, are a little pixilated [sic].’ In 1937, a columnist at The Washington Post admits (ironically) to fearing being caught doodling ‘dogwood blossoms’ while chatting on the telephone and being goaded with ‘that fatal form of neurosis known as “pixillated”.’ As one popular columnist surmises: ‘a hundred million guinea pigs are now “doodles”-conscious’ – both in thrall to doodling and in fear of the wisecracks it’ll inspire. Also in 1937, Life magazine publishes funny exposés of doodling politicians and doodling celebrities alongside a feature on the New York subway’s pixillated ‘photo-doodlers’. What matters here is the doodle’s containment of a ‘pixillated’ comedy of neurosis, skewering the period’s po-faced ‘science’ of dreams while celebrating errant expressions of all kinds.

Gertrude Stein meets Albert Einstein photo-doodle in ‘Speaking of Pictures… These Are Photo-Doodles’ in Life (2 August 1937). Supplied by the author

These burgeoning pop cultures celebrating the American public’s democratic respect for minor differences coincided with, and were fed by, a growing interest in psychoanalysis and the unconscious colliding with older (largely Western European) avant-garde, occult and pseudoscientific interests in planchette writing, graphology, automatism and free-association parlour games. In Life magazine’s 1930s showcasing of subway photo-doodles and doodling Democrats, for example, explicit parallels can be drawn with Marcel Duchamp’s Dada portrait of the Mona Lisa in L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) and Louis Aragon’s recycling of the discarded doodles of French ministers in the magazine La Révolution surréaliste in 1926. In turn, Russell Arundel’s cartoonish doodle catalogue, Everybody’s Pixillated (1937) – ‘a pixillated book for pixillated people’, published hastily in the wake of Mr Deeds Goes to Town – owes as much of a debt to late-19th-century graphology textbooks that attempt to taxonomise character through handwriting as it does to the highbrow strictures of Freudian psychoanalysis.

L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) by Marcel Duchamp. Courtesy Wikipedia

Cover of Everybody’s Pixillated (1937) by Russell Arundel. Courtesy the Centre for Book Arts

The doodle skirts close to an irreverent form of psychoanalysis for the people

Graphological understandings of the modernist doodle catalogue are more evident still in Your Doodles and What They Mean to You (1957) by Helen King:

The signature shows the personality – that side which we appear to be to the public. The penmanship shows the character – that which we really are. And the doodles tell of the unconscious thoughts, hopes, desires. [my italics]

King’s pop-ish sense of doodles as the cartoon sigla of modernism’s unconscious folds back readily into the avant-garde surrealist’s interest in parlour games like ‘exquisite corpse’, which topologically enfolds an assemblage of individual doodles into a grotesque vision of Jung’s collective unconscious.

To be sure, as they erupt across modernist pop culture, doodles often parody these older and more serious concerns of graphologists, occult automatists, avant-garde surrealists and early psychologists. As if referring back to Mr Deeds’s comic analysis of Dr Von Haller’s doodles, the doodle comes to the fore as a tongue-in-cheek expression of a re-materialised unconscious that is more inclined to poke fun at the elitism and highfalutin snobbery saturating interwar modernist psychoanalytical practices than to posit any serious means of understanding dreams. This said, in preferring to simply celebrate the silly things people do to help them think (to paraphrase Mr Deeds), the doodle skirts close to an irreverent form of psychoanalysis for the people. Like the modernist doodle, the graphologist’s doodle upholds the value of democracy through its informal containment of difference.

A surprising number of interwar modernist novels contain characters who erupt with dawdling forms that are in close dialogue with late-Victorian practices of automatism and graphology. In Virginia Woolf’s novel Night and Day (1919), for instance, Ralph Denham gazes absently into a page riddled with ‘half-obliterated scratches’ and a ‘circumference of smudges surrounding a central blot’, before beginning to doodle ‘blots fringed with flames’. Instantly, Ralph finds his lawyerly way of inhabiting the world softening, opening onto a network of what Helen King called ‘unconscious thoughts, hopes, desires’. Drawing on the occult practice of planchette writing, Woolf has Ralph find the ‘objects of [his] life, softening their sharp outline’ as the doodle mediates first a kitsch image of cosmic totality, and then his genuine human connection with the woman he loves, the upper-class Katharine Hilbery. For Katharine immediately recognises something familiar in ‘the idiotic symbol of his most confused and emotional moments’. ‘Yes,’ she says in rational agreement with Ralph’s irrational doodle, ‘the world looks something like that to me too.’

The modernist’s will-to-doodle folds out still more explicitly and wonderfully in Joyce’s ‘verbivocovisual’ Finnegans Wake. Apropos of the media frenzy surrounding Mr Deeds Goes to Town, Joyce adds in numerous references to the ‘doodling dawdling’ antics of his dream novel’s cast. ‘He, the pixillated doodler,’ writes Joyce, ‘is on his last with illegible clergimanths boasting always of his ruddy complexious!’ The reference is to Shem the Penman’s terrible handwriting in his transcription of a letter by his mother, Anna Livia Plurabelle (ie, ALP).

The social affordance of the doodle contains both ecological and democratic differences

The letter itself is a muddied and crumpled communicative mess that echoes Finnegans Wake’s own erratic and polyphonic form. ALP’s doodle-laden pixillated letter is a non-sovereign projective field of subjects and objects all mixing and mingling in ‘strangewrote anaglyptics’, wherein the voice of Anna Livia blurs not only with Shem’s ‘kakography’ but also with ‘inbursts’ from Maggy (ie, Isobel/Issy/Girl Cloud, and ALP’s only daughter with HCE, ie, Here Comes Everybody/Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker), and an array of more-than-human gestures, from tea stains and orange-peel smudges to chicken scratches, electromagnetic wavelengths, muddy splashes and more. Regurgitating what Stephen Dedalus in Joyce’s earlier novel Ulysses (1922) calls the ‘signatures of all things’, ALP’s doodle-laden letter is both an indelibly human and more-than-human form that foregrounds the marginalised signatory gestures of subjects and objects alike: rivers; men; orange-peels; Morse code machines.

For all of Joyce’s interest in Mr Deeds and the rise of modernism’s ‘pixillated doodlers’, the meaning of the Wake’s doodles again blurs with an older, late-Victorian interest in graphology. As Walter Benjamin writes in 1928, ‘graphology is concerned with the bodily aspect of the language of handwriting and with the expressive aspect of the body of handwriting.’ With Shem’s/ALP’s pixillated letter, Joyce explodes this ‘body of handwriting’ into an intermedial and non-anthropocentric ecology that brings together the animate gestures of chickens, medieval high priests and supersonic televisions. Rejoicing in the many-in-oneness of all expression – or ‘the identities in the writer complexus’ – Joyce dwells on the poetry of a letter’s variegated surfaces. Its ‘stabs and foliated gashes’; its ‘curt witty wotty dashes’ and ‘disdotted aiches’; its ‘superciliouslooking crisscrossed Greek ees’ and ‘pees with their caps awry’; its ‘fourlegged ems’ and ‘fretful fidget eff[s]’; its ‘riot of blots and blurs and bars and balls and hoops and wriggles and juxtaposed jottings linked by spurts of speed’.

From Joyce we learn that the social affordance of the doodle contains both ecological and democratic differences. A healthy public depends on a healthy planet, and both begin by recognising that everyone – and indeed everything – is a doodler.

In the postwar period, and eventually in pop culture, the modernist doodle takes on an increasingly cartoonish and commodified form. The more doodles circulate, the more they become pastiches of themselves (meaningless sigla imbued with oversized meanings, parodies of an all-too-formulaic commitment to formlessness). In Robert Arthur Jr’s satirical story ‘Mr Milton’s Gift’ (1958), first published in Fantasy and Science Fiction, we find the hapless Horace Milton ‘sitting back, daydreaming and doodling … doodling something while daydreaming about being rich’. Following a mysterious ‘charm’, Horace Milton’s lazy doodles come to constitute a bizarre late-capitalist labour-saving device, as he realises ‘he hadn’t just been doodling. Unknown to him, his hand was drawing a perfect hundred dollar bill.’ The modernist doodle is here remade in the parodic vision of a post-modernist America, defined not by the democratic containment of difference but by the hypercommodification of everything. Not least, the collective desire to ‘daydream about being rich’. The play of difference and irreverence celebrated by Mr Deeds – and his ‘insane desire to become a public benefactor’ – is absorbed into a homogenising pursuit of capital.

Throughout the post-1945 period, the doodle has been further sterilised, homogenised and hypercommodified into an increasingly ‘game-changing’ neoliberal form of ‘creative power’. Think of ‘Google Doodles’ (1998-), or business management gurus styling themselves as ‘info-doodlers’, for example. The modernist doodle’s non-hierarchical formalism has been flattened and its sociopolitical errancy standardised in overwrought simulations of spontaneity. Into the early 21st century, the postmodernist doodle tends to help brands and corporations disguise systemic agendas of extraction and exploitation in colourful and fun-loving – squiggling and non-sovereign(!) – surfaces full, as Google says, ‘of spontaneous and delightful changes’.

Yet I cannot help but wonder: what if the doodle rekindled its modernist errancy and rediscovered its democratic roots? The doodle’s history points to an indelibly American form of ‘being in the impasse together,’ as Lauren Berlant says in Cruel Optimism (2011), meaning that it helps us to imagine a non-classical kind of collectivity that foregrounds a non-hierarchical communion of marginal differences. As Gilles Deleuze once said of that exemplary modernist Dödel, Charlie Chaplin, the struggle is to find a form that ‘make[s] the slight difference between men the variable of a great situation of community and communality (Democracy).’ The original social agency of the doodle is clearly formed by a promiscuous ability to bring people together by way of popularising their errant and wasteful gestures – gestures once confined to the peripheries of occult automatisms, pseudoscientific graphology manuals and obscure surrealist practices. The question now is: how might the doodle recover this capacity to put the play of marginal differences to work as socially generative form? In a time when democracy seems once more under threat, how might the doodle rekindle its long-lost power to inspire pixillated dreams of togetherness?