Shoreditch, east London, is home to a remarkable cluster of technology start-ups. Dozens of web and ‘new media’ firms, including Last.fm and TweetDeck, set up shop here and make this grimy but beguiling district their home. No one decided this would happen. It was urban alchemy — the chance intersection of multifarious factors of money, technology, education, culture, time and space, which locked into a temporary virtuous feedback loop, long before the politicians arrived and tried to take credit. Although bathed in broadband glow and old-media hype, what these companies actually do is ancient, primal: they build tools. Within a few blocks are hundreds of people devising new applications for digital technologies — new ways of bringing the electronic global network to bear on life.

It’s in these streets that the boundary between the digital and the physical is at its most porous — in the devices and the minds of a far-seeing local population who are among the first to understand that there might not be a boundary at all. And strange phenomena can arise in this technological crucible. In May 2011, a British writer and technologist called James Bridle set up a blog on the social networking service Tumblr.com to document a few of the phenomena he had seen. Tumblr favours images and snippets of video and text, which is exactly what Bridle posted, a stream of images, screenshots and video, backed up with an occasional quote or sentence of commentary. Among the images posted on the first day were: a photo of the screen of a cathode-ray television at the moment it is switched off; examples of make-up that could be used to defeat face-recognition software; Osama bin Laden’s hideout in Pakistan as it appears on Google Maps; and fighter jets with a camouflage of blocky patterns suggestive of pixels.

Join the dots. Find the thread. What links those images? They share a veneer of digital modernity, perhaps, but what else?

Bridle, an expert on digital publishing and a member of the Shoreditch-based design partnership the Really Interesting Group, or RIG, called it a ‘mood board for unknown products’ in a post on the group’s blog. Mood boards are collages made by designers to piece together the visual inspiration behind a project. Here, though, there was no project beyond the collage itself. Bridle called the Tumblr, and the undefined product it represented, the New Aesthetic. And he continued in the same vein, trawling through the crackling, accelerating networked world. Satellite images of server farms, those giant, anonymous sheds where machines crunch out the internet. People dressed in costumes as low-resolution characters from the computer game Minecraft. A label on a pair of jeans bearing nothing more than a line of Excel code, a bug in a clothing factory manifesting at the other end of the supply chain. Oddities from Google Street View — seagulls, prostitutes, security black spots. Scenes from the drone age. Rough-edged, lo-fi objects produced by 3D scanning and 3D printing.

Converging, leapfrogging technologies evoke new emotional responses within us, responses that do not yet have names

The spectral outline of something swims into view: the way machines see. The spread of robot eyes — on phones, on drones, on buildings, on satellites, on Google vehicles, on us. The way machines show us things, and the spread of screens. The rise of augmented reality, the insertion of digital constructs into real landscapes. The way things appear to us when they are mediated, somehow, by digital machines — the data centres, the mechanised production lines and logistics centres, the LCD-bathed outlets. Oddities and idiosyncrasies brought into view by this machine mediation of the stuff around us — the robot inflection, the accent of media devices. Bridle’s one-sentence summary of it all is ‘an eruption of the digital into the physical’.

Intuitively, one feels that this could be important. Smartphones, tablet computers, drones, CCTV cameras, LCD screens, e-readers, GPS, social networking, recognition algorithms and scores of allied technologies and concepts are rising to super-ubiquity around us. They are wreaking untold changes on the behaviour of nation states, corporations and individuals. Yet all this is happening in a cultural environment broadly evacuated of ideology, apart from the exhausted fairytales of neoliberal consumer capitalism. At least the New Aesthetic could be new; really, truly new. Indeed its outer contours suggested frightening, exhilarating novelty, something rare in this paradoxical age of astonishing technology set against jaded and reflexive nostalgia.

At this stage, the New Aesthetic was just those images and a few lines of text — and that feeling, that hunch. Still, it wasn’t just Bridle’s hunch. ‘People responded really strongly,’ he said when I spoke to him a year on from his first blog on the New Aesthetic. ‘But a very small number of people — people I know.’ Those people tended to occupy the same inventive media-technology niche as Bridle — a small community concentrated in east London and on the West Coast of the United States.

Matt Jones, one of the three principals at the celebrated creative studio BERG, which shares premises with RIG in Shoreditch, wrote a long blog entry trying to define the New Aesthetic as ‘sensor vernacular’ and ‘an aesthetic born of the grain of seeing/computation … Of computer-vision, of 3D-printing; of optimised, algorithmic sensor sweeps and compression artefacts’. Warren Ellis, an author who occupies a curious role as intellectual patron for this corner of the London design and technology scene, linked to the post from his well-trafficked website, sending thousands of interested eyes in Bridle’s direction.

This first small flurry of interest encouraged Bridle to persist with the New Aesthetic project, despite its lack of a clear identity, aims or boundaries. But the Tumblr was also an effort at what Bridle calls ‘self-correction’ — refining his terms, adjusting and clarifying a still-inexpressible concept. ‘It’s not a prescriptive thing,’ said Bridle. ‘It’s a gradual collection in order to find the edges of something … Not all the examples definitely belong to it, and that’s OK.’ The New Aesthetic was a Rorschach blot. Its low resolution meant that all observers could project their own meaning into it.

But before Bridle was able to establish what it all really meant, the project was snatched out of his hands.

I met Bridle in Allpress, a coffee shop in Shoreditch (of course), on May 4, 2012. After the interview we walked down Redchurch Street towards Shoreditch High Street. Facing us, a building was under construction, its scaffolding wrapped in mesh. The mesh was decorated by a QR code — the blocky black-and-white patches that, using a recognition algorithm available as a free app, will connect your smartphone to a website. Still fairly novel, this technology is being used with mindless abandon by advertisers and developers. Often the code is useless — because it’s on a poster underground, where phones usually can’t connect to the internet, or because the code has been badly positioned or is split or partially obscured. A blog cataloguing these QR-code foul-ups was linked from the New Aesthetic Tumblr. This code on Shoreditch High Street was only half visible, and thus unusable — but this appeared deliberate. Rather than just being badly applied, the code was being used purely as a decorative device.

Very New Aesthetic. We paused and Bridle took a photo on his phone. Later, the picture went up on the New Aesthetic Tumblr. It was the last post. On 6 May 2012, its first birthday, the account was shut down. What happened?

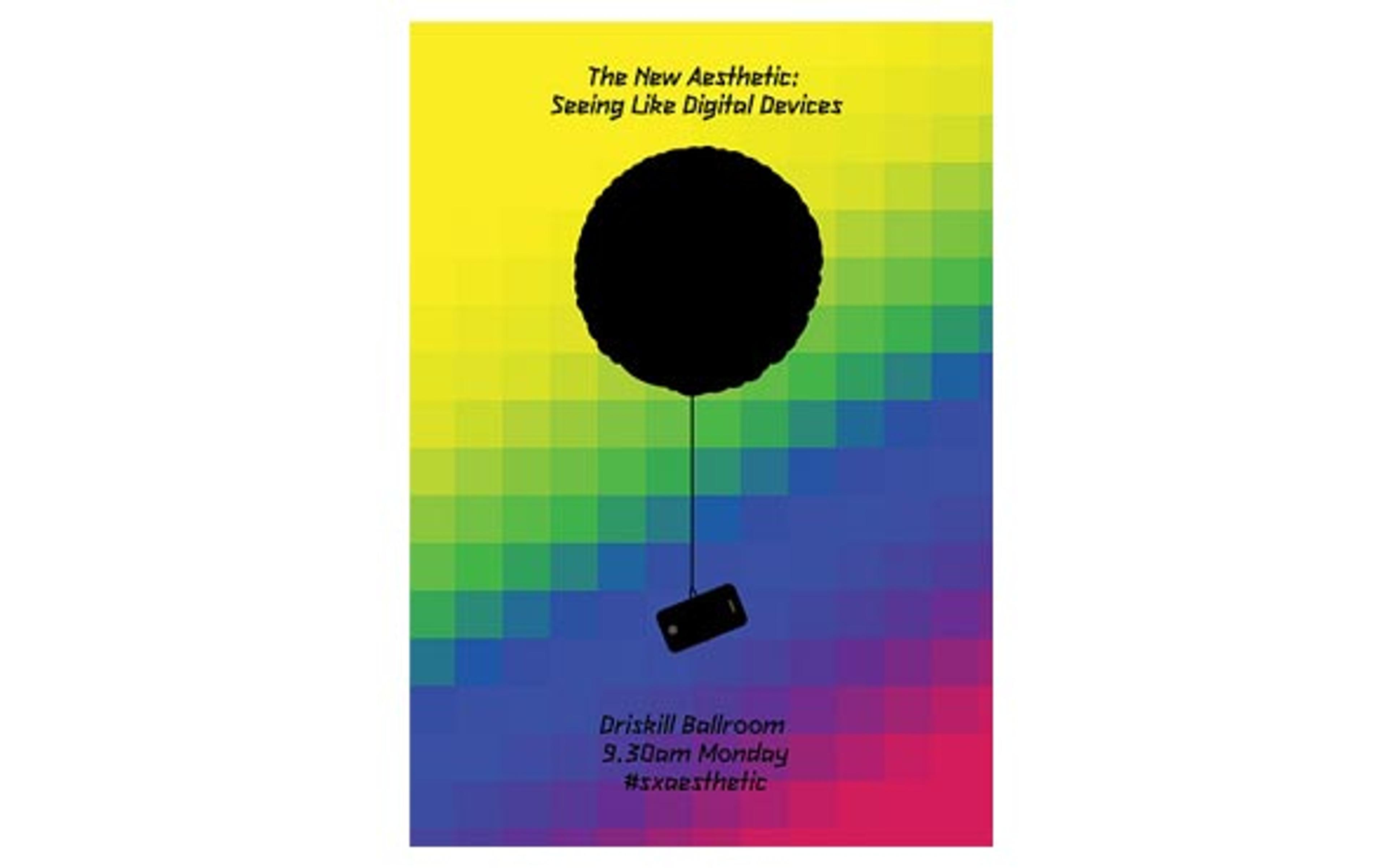

This March, Bridle chaired a panel on the New Aesthetic at South by Southwest (more commonly, SXSW), a voguish music and technology festival held each year in Austin, Texas. His own presentation on the evolving project was reinforced by presentations by Russell Davies, founder of RIG; Joanne McNeil, the editor of the technological arts website Rhizome; the artist Aaron Straup Cope; and the designer Ben Terrett. The phenomenon was to be set in its proper historical context and differentiated from mere neophilia.

‘Yes, everything has always been new and different, and everything has always been the same,’ Bridle wrote in the summary of his presentation, ‘but we can perform an end-run around this endless back-and-forth …’ The novel ways of seeing suggested by the New Aesthetic promised, ‘if not a new world … then new sensations, which are the medium by which we appreciate a new world.’ Converging, leapfrogging technologies were evoking genuinely new emotional responses within us, responses that do not yet have names. That frisson of wonder when we use Google Street View to scout out a place we haven’t been yet or maybe never will; that shiver at the thought of lethal strikes by unmanned drone aircraft or an end to privacy. The New Aesthetic was setting out to map those reactions. ‘Meaning is emergent in the network, it is the apophatic silence at the heart of everything, that-which-can-be-pointed-to,’ Bridle said in his presentation. ‘And that is what the New Aesthetic, in part, is an attempt to do … to point at these things and go “but what does it mean?” ’

The group took as its logo a pixelated predator drone supported by balloons, ‘a bright cluster … tied to some huge, dark and lethal weight’, as the science fiction author Bruce Sterling put it. He was watching the panel.

Via his Beyond the Beyond blog for Wired magazine and his appearances at conferences and symposia worldwide, Sterling has carved a reputation as one of the most admired thinkers on contemporary technology and society. Because of his status as a high prince in the techno-intelligentsia, he was invited to deliver the closing address at SXSW. He singled out the New Aesthetic for specific mention, and the following month published a 5,000-word essay on it:

The New Aesthetic is one thing among a kind: it’s like early photography for the French Impressionists, or like silent film for the Russian Constructivists, or like abstract-dynamics for Italian Futurists. … we have every reason to take it, and its prospects, seriously. … This is one of those moments when the art world sidles over toward a visual technology and tries to get all metaphysical. This is the attempted imposition on the public of a new way of perceiving reality. … Above all, the New Aesthetic is telling the truth.

Bridle was ‘master of that salon’, wrote Sterling, ‘[He] has never yet claimed to be the André Breton-style Pope of the New Aesthetic, but in practice, nobody ever asks the central questions of anybody else but him. So, Bridle’s the guru there. Fine.’

The first Bridle heard of Sterling’s intervention was when ‘everyone on Twitter started talking about it’. Wired’s own metrics show more than 1,000 tweets directly linking to the piece. From those, scores of conversations started. The New Aesthetic is not the easiest idea to communicate, yet all of a sudden thousands of people were energetically generating opinions on it. ‘Initially,’ Bridle said, ‘I was quite flattered.’

The day Sterling’s essay went live, all the existing literature on the New Aesthetic could be consumed in an afternoon. Within a couple of weeks, blog posts were being generated faster than they could be read. It seemed everyone had something to say about the New Aesthetic.

Naturally enough, there were parodies — a doppelganger blog called the New New Aesthetic, which lasted all of two posts, and a cat-based lampoon called the Mew Aesthetic. And of the more serious responses, not all were positive. A blog called The Creators Project published a series of essays on the subject. One claimed that the New Aesthetic wasn’t new, had very little shock factor and had a ‘disappointingly stuffy’ name. This was tame compared to a contribution from the curator Hrag Vartanian, which stated that not only was the New Aesthetic not new, it wasn’t an aesthetic, it was a style without any meaning, a hopelessly retro throwback to the bits of recent past that were ‘easily Googled’, and blind to broader cultural history. Maybe, Vartanian mused, Bridle had suffered a head injury.

‘Quite quickly,’ Bridle said, ‘I stopped reading anything about it.’

The fundamental problem was that Sterling’s essay had described the New Aesthetic as a movement. The word suggests membership, doctrine, methods and goals. An agenda. And this movement, said Sterling, was moving into its ‘evangelical, podium-pounding phase’. This was death. ‘As soon as you declare something a movement, everyone either wants to be a part of it or wants to destroy it,’ Bridle said. ‘I couldn’t even look at Twitter, because there were people @-ing me, saying “What is this bullshit?” ’

The storm of controversy resembled a denial-of-service attack. ‘It rendered my social networks almost unusable. I couldn’t continue to talk about it because anything I said about it was lost in that mass.’ Two days later, he shut down the Tumblr.

But in a way, Bridle was vindicated: the volume of the response shows he had struck something fundamental — as well as communicable and highly provocative. ‘I would deny it’s a movement because that’s not what I intended it to be,’ he said, ‘but there’s a vacuum for the movement that people think it is. Which is something genuinely of the network. They want the new modernism, and it has to come out of the network.’

Sterling had hinted at this, in a line from his first essay that now feels prophetic: ‘Everybody who attempts [to explain the project] seems to hope and feel that the New Aesthetic must be a private solution to their own personal creative problems.’ Bridle had given a name to a mythical beast that no one has seen directly but, it turns out, lots of people were hunting for: the JPEGwocky.

Looking at some of the mistaken impressions about Bridle’s project — what it isn’t — does help to clarify what it is. As well as not being a movement, it is very much not an art movement, although some artists are creating work that fits into it. Sterling is responsible for this confusion, calling it ‘a typical avant-garde art movement that has arisen within a modern network society’. This set up the New Aesthetic to be denigrated by the art world (which saw it as nothing of the kind) and to be pigeonholed as art by everyone else.

This is unfortunate, not least because Sterling’s essay also furnished us with some helpful terms for what the New Aesthetic actually is. He called it a ‘gaudy, networked heap’, and better than that, a wunderkammer, a cabinet of curiosities — geodes, two-headed lambs, bits of coral — that were assembled by hungry minds in Enlightenment Europe. The wunderkammer is part of the first act of modern science — astonishment at the oddities of the natural world, which whets the appetite for inquiry. ‘A heap of eye-catching curiosities don’t constitute a compelling world-view,’ Sterling wrote. Perhaps not, but it’s a start.

51 per cent of Americans believe stormy weather can interfere with cloud computing

Another recurring charge was that the New Aesthetic was somehow nostalgic or retro. This originates in the recurring appearance of pixelation and low-resolution graphics as a New Aesthetic motif. A roadside sign resembling a giant Facebook ‘Like’ button, pixels the size of dinner plates, or sculptures composed of hundreds of coloured cubes, looking like something that has stumbled out of a computer game — this kind of thing was a regular feature on the Tumblr. And Bridle also had an eye for less knowing appearances of digital textures, such as in the pattern given to the tail fin of a German jet. This is what happens, he says, when a generation raised on the distinctive, blocky 8-bit graphics of the 1980s grows up and starts addressing the world around it. True enough, but this observation contributes to an impression of the New Aesthetic as being generated by 30-something boy-men hankering for the Super Mario of their lost innocence. Sterling was scornful: ‘Sentimental fluff for modern adults’. Pixelation might rupture the interface between the digital and the physical, but it’s ‘a cute, backward-looking rupture’.

Well, only up to a point. Firstly, this criticism fails to distinguish between the people who make that sort of work and the curators of the New Aesthetic, who are looking for it. Designing a pixelated shop sign while lost in a reverie about Castlevania video game is nostalgic. It is far less nostalgic to ask why people are decorating their world in this way.

In a sense, what the New Aesthetic truly represents is the eruption of a new kind of banality. It is the arrival of digital motifs, glitches and artefacts in the realm of the commonplace and the trivial, the advent of a world where it is thoroughly normal to see a Windows crash screen in place of an advertisement on the Underground, or for trading algorithms to cause a stock market crash. So it’s not truly new — the newness is beside the point. The fascinating thing about the New Aesthetic could be that it was never new — it went from being unknown to being ubiquitous and thoroughly banal with barely a blink. The frisson of shock or wonder one experienced at seeing an aspect of the New Aesthetic out in the wild comes because that is the only time it will be noticed; afterwards it will pass unobserved. The New Aesthetic is not about seeing something new — it is about the new things we are not seeing. It is an effort to truly observe and note emergent digital visual phenomena before they become invisible.

Is, or was? After Bridle shut down the Tumblr, it was hard to see if the New Aesthetic would continue as a phenomena at all. There was a steady stream of blog posts and online discussion, and there are occasional outbursts of activity, such as a ‘sprint book’ on the subject produced by V2, a Rotterdam centre for art and media technology. But without the tick-tock of Tumblr posts, a crucial element of momentum seemed lacking. And then, on 20 August, without fanfare, the Tumblr resumed. Images of the disintegrating holographic ghost of Freddie Mercury from the Olympic closing ceremony; Twitter fatwas by Islamic clerics; an automated car park closed down by a software licensing dispute; the news that 51 per cent of Americans believe stormy weather can interfere with cloud computing. The New Aesthetic was back in business.

This matters because it was a kind of warning. Digital technologies are transforming social, economic and political relations. If these transformations take place invisibly, if they become banal too fast, we are placed in danger. The infrastructure of the internet — its servers, its logistic hubs — are in anonymous sheds, yet we are encouraged to think of this immense deployment of capital, equipment and expertise as a ‘cloud’, an image that has obviously had an influence on 51 per cent of Americans.

Great value is placed on ‘seamlessness’— bigger, better LCD displays that connect better with their surroundings; connections between our bank accounts and mobile phone accounts and loyalty cards; personal devices that talk with each other and compare notes on our data; augmented reality. The virtual world is being integrated with the physical world and this seamlessness is presented as inherently good. No harm may be intended: it’s natural for a designer to want to smooth away the edges and conceal the joins. But in making these connections invisible and silent, the status quo is hard-wired into place, consent is bypassed and alternatives are deleted. This is, if you will, the New Anaesthetic. Instances of the New Aesthetic are often places where a glitch has exposed the underlying structure — the hardware and software. Or it is an oddity that has the unintended side effect of causing us to consider that structure. Part of a plane appearing in Google Maps makes us realise that we are looking at a mosaic of images taken by cameras far above us. We knew that already, right? Maybe we did. But a reminder may still be salutary.

This is political. The New Aesthetic was accused of being apolitical — fascinated by the oddities and wonders being thrown up by drones and surveillance cameras without thinking about the politics behind them. This is plain wrong: politics seeps from nearly every pore of the New Aesthetic. It was often hard to see, but that’s what Bridle wanted to expose.

The question is one of viewpoint. ‘As soon as you get CCTV, drones, satellite views and maps and all that kind of stuff,’ Bridle said, ‘you’re setting up an inherent inequality in how things are seen, and between the position of the viewer and the viewed. There are inherent power relations in that and technology makes them invisible. When you have a man in a watchtower, you look up at him, and that’s an obvious vision of power. When the man is in a bunker far away and you have just a little camera on a stalk … most people seem to be fine with that.’

The New Aesthetic is about seeing, then. And to see and be seen is to engage in those power relations. It might be that the New Aesthetic, as the writers Madeline Ashby and Rahel Aima have both said, is simply men waking up to the sensation of being under surveillance, something women have long experienced in the form of the ‘male gaze’. The riotous spread of new technologies of seeing — not just thousands of new cameras, but also recognition algorithms and other software and hardware that can detect a presence or identify an individual — is subjecting these power relations to constant flux, and the outcomes could be dangerous. The New Aesthetic was the outer froth of this silent social turmoil — the project was to make it legible. ‘By legibility I mean our own ability to read these systems, how much they can affect the way we see and act in the world, and the differing positions of power we have in the world based on how legible those systems are,’ Bridle said. ‘The programmers have a huge amount of agency in the world, because they can deconstruct, reverse engineer and write and construct and create these systems. People who can’t, don’t, and they have less power in the world because of it.’

Observers of the New Aesthetic from outside the worlds of media technology and programming might be tempted to pass off the phenomenon as something only of importance within that world. In doing so, they disenfranchise themselves. Yes, the New Aesthetic is the product of a small, specialised media-technology niche. But it’s a huge mistake to ignore it. The people inside are trying to get a message out.