Night: and once again, the nightly grapple with death, the room shaking with daemonic orchestras …

– from the novel Under the Volcano (1947) by Malcolm Lowry

Back in my student days in late 1970s Paris, one of my favourite walks would take me to the fabulous Père Lachaise cemetery near the eastern edge of the French capital. A miniature city of monumental tombs and crypts in a lush garden setting, it has long been ‘home’ to the remains of no small number of the very special dead: Molière, Oscar Wilde, Colette, Sarah Bernhardt, Chopin … and Jim Morrison. Morrison’s gravesite was always part of my itinerary, because it was a gathering place for a colourful array of people paying their respects with flowers, notes and a few tokes on something vaguely illegal. A stone bust of the Doors’ legendary frontman had already been completely chipped away by the time I started visiting the site, however what remains today is a bronze plaque engraved with his name, his dates (1943-71) and an epitaph in Greek. Kata ton daimona eaytoy may be read in a number of ways, figuratively as ‘true to his own spirit’, but also literally, ‘true to his own daimon’ or ‘by the favour of his own daimon.’ What or who could have been Jim Morrison’s ‘own daimon’?

Some 25 centuries before Morrison’s time, Plato’s daimons were something akin to guardian angels, spirits that watched over the living, whom they guided on the path to Hades after their death. Well before Plato’s time, Homer had referred in the Iliad to the Olympian gods themselves as daimons. Also referred to as daimons were the denizens or guardians of prominent and often forbidding features of the natural world – mountaintops, forest groves, caverns and springs – supernatural beings with oracular powers. Quite often, however, the daimons of ancient Greece were dire, hostile, dangerous spirit beings, the evil eye demon (baskanos daimon) being an illustrious example.

What these conflicting usages tell us is that the daimons of the ancient world were ambiguous beings, spirits with varying degrees of power that they could employ, or be made to employ, for good or evil ends. This is how they were portrayed in the Christian Bible where, in the Book of Matthew, Jesus admonished his disciples to ‘heal the sick, raise the dead, cleanse the lepers, and cast out demons.’ These daimons (translated as ‘demons’ in the English Bible) were unambiguously noxious, so that, when Jesus exorcised them, their victims were released from their sufferings. Such was the case of Mary Magdalene herself, ‘from whom he had cast out seven demons’. Yet, these same daimons were also cast as spirits capable of recognising and conversing with Jesus: ‘And he healed many who were sick with various diseases, and cast out many demons; and he would not permit the demons to speak, because they knew him.’

The demons of the Christian Bible were none other than the daimons of paganism demoted, that is, the lesser divinities of the Greco-Roman religion superseded by Christianity after Rome’s conversion to Christianity in the 4th century CE. Thereafter, the triumphant Church would condemn this ancient host, this pandemonium, to the dark side. Fallen angels, forces of evil, agents of temptation, these were now demonised as hell creatures toiling in the service of the prince of darkness: Lucifer, Satan, the Antichrist, the Devil. In the face of these supernatural enemies, the Church would quickly mount an arsenal of countermeasures, and so the applied science of Christian demonology was born. This is not to say that Christianity was the first or the only great religion to forge a demonological lexicon. Centuries, even millennia before the Greeks and Romans, the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians had developed a variety of techniques for combatting malevolent demons. And, in fact, every one of the world’s religions has had a demonological component for battling their inner demons.

Demonology, the ‘science of demons’, has always comprised two complementary facets – the one theoretical and the other practical. If one was to battle one’s enemy effectively, one first had to know him, his human confederates, his disguises, his ruses. I use the singular here, because in many of the world’s religious traditions, the demonic hordes were held in the thrall of a single great embodiment of evil, an arch-rival to a benevolent God or gods. The relationship between the demonic host, the pandemonium, and its master was envisioned in several ways. Quite often, the demons were simply a protean swarm, overwhelming by their sheer numbers, visiting natural disasters and plagues upon the land, and madness, sickness and death upon their human victims.

In some cases, however, the pandemonium was imagined as a hierarchy whose structures mimicked those of human institutions or divine pantheons. For the monks of medieval Catholicism, the organisation of the demonic host replicated its own hierarchy. In the same way that the good angels were ranked according to their stations and functions, so too with the evil spirits: our bishops had their counterparts in their bishops, our abbots in their abbots, our priors in their priors, and so on. Sometimes, the pandemonium was theorised as a military organisation, as for example in a 5th-century Taoist work, the Book of Divine Incantations for Penetrating the Abyss, which imagined battalions of demon armies with a command structure ranging from generals to petty officers, cavaliers, infantrymen, archers, spies and executioners.

Demons inflict much of their evil on the world through humans

For the Zoroastrians of pre-Islamic Persia, each shining angel of ‘truth’ had for its counterpart a darkening demon of ‘the lie’, with the supreme good spirit Ahura Mazda pitted against the arch-demon Ahriman. An early Buddhist demonological treatise, the Teaching of the Great Pea-Hen, the Queen of Spells, organised its demons as if they were members of a noble household: masters and mistresses, sons and daughters, chamberlains, ladies in waiting, and male and female retainers. For well over a millennium, the Hindu pandemonium has been ruled by one or another powerful tantric god or goddess, called a master or mistress of spirit beings. Unless and until these dominant figures are shown respect in the form of offerings of various sorts, they will allow their minions to prey upon a defenceless humanity, infants in particular. Once gratified, however, they become fierce defenders of the same persons they had allowed to be victimised. Similarly, in the Taoist work just cited, demon kings and generals could be coerced by the gods of heaven to purge and destroy the billions of spirits in their own demon host.

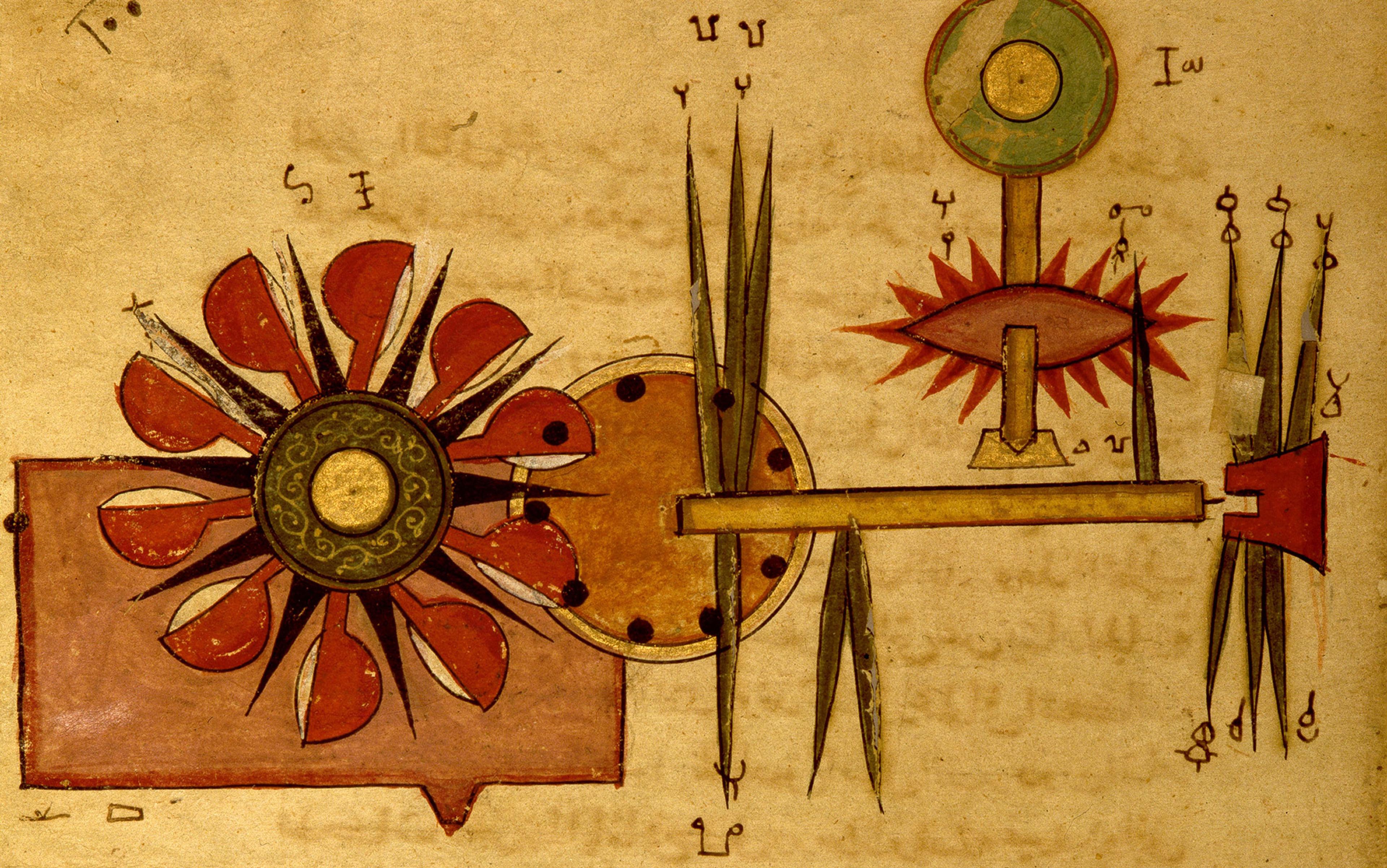

Practical or applied demonology, the strategies deployed to counter demons, can be classified under two headings, which we may call the carrot and stick approaches. The first is that just described: prevailing upon a powerful demon to bring to heel his subordinates, the lesser demons of human afflictions. Far more common is the strategy of the stick: full-on combat against demonic possessors or their human agents. This is generally a two-step process, beginning with a trial. Demons inflict much of their evil on the world through humans, whether these be their hapless victims or willing confederates: witches, heretics and foreigners. In all cases, the possessing demon must first be identified. This is the work of the inquisitor-exorcist who, through a mixture of cajoling, coercion and threats, compels the demon to pronounce its name. Then follows the exorcism, a violent procedure (often involving torture, in the case of witches), culminating in the demon’s exit from the body, via the mouth or anus. The drama of possession and exorcism have been portrayed on countless works of art, from medieval Nepali manuscripts to a French Book of Hours.

Demon possession, Nepal, 1540 CE. Courtesy of Wellcome Trust/Wellcome alpha1937

Christ exorcising a demon, from Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, 15th-century France. Courtesy Wikimedia

However, this is not the whole picture, because, generally speaking, it was only these inner daimons of possession that were potentially ‘demonic’. When approached in the proper manner, the custodians of springs and rivers and sacred groves, like Plato’s guardian spirits or the various oracles of the ancient Mediterranean world, have shown themselves to be of a benevolent sort, and so have been sought out by persons in need of their help. Fairies, trolls, elves, nymphs and gnomes are so many ‘land spirits’, daimons of the natural environment. So it was that, when faced by their parishioners’ stubborn recourse to the healing waters of pagan sanctuaries, the same medieval Church whose vocation it had been to combat the demonic hordes was forced to yield to popular custom. Even today, the Mediterranean world is dotted with thousands of pools and springs consecrated to various saints and virgins who are none other than the daimons and fairies of yore, overlaid with the slightest Christian veneer.

Notre-Dame des Douleurs, Garrosse, France. Photo supplied by the author

Fontaine Sainte-Luce, Escource, France. Photo supplied by the author

The same strategies were employed in Hindu and Buddhist South Asia, where the ancient daimon custodians of mountains, forest groves and pools were most often called devatas (‘divinities, daimons’), yakshas (‘dryads’) or rakshasas (‘guardians’). These potentially dangerous spirit beings were often appeased, even domesticated, by worshipping and granting them the status of subordinate protective deities. In Buddhist scripture, this adaptation was often scripted as a ‘conversion experience’. One of the Jatakas, the Buddha’s ‘Birth Stories’, describes just such a transformation on the part of the water guardian of a sylvan pool who had been authorised by the king of the yakshas to pose a series of questions on ‘yaksha law’ to any person who would come to drink from the pool – and to eat those who could not provide the correct answers! Coming there in disguise, the Buddha answers the water guardian’s riddles and so impresses him that he converts to the saddharma (True Law) of the Buddhist faith.

Many of these South Asian daimons were eventually incorporated into the pantheons of the great religions, in some cases becoming enshrined as powerful saviour figures. A well-known example is that of an arch-demoness named Hariti, the ‘Baby Snatcher’. Notorious for devouring hundreds of children, she is convinced by the Buddha of the folly of her ways, after which she becomes the revered protectress of the same infants she had previously victimised. Images of Hariti, found across the Buddhist world from Inner Asia to Japan and Indonesia, invariably portray her surrounded by babies – held in her arms, clutching at her breast, and playing at her feet. According to a medieval scripture from Hindu India, a yaksha prince named Harikesa (‘Redhead’) underwent a similar transformation. Renouncing his demonic ways to become a devotee of Śiva, he was appointed the leader of the great god’s minions and installed as guardian of his principal temple in the holy city of Varanasi.

Carving of Hariti (c824 CE) from Chandi Mendut temple in Borobudur, Java, Indonesia. Photo by Patrick Young and courtesy the ACSAA/University of Michigan

Like their homologues in the Western world, Asia’s daimons are an ambiguous lot, by turns benign and malign, powerful and vulnerable, innate and remote, earthbound and aerial, inert and evanescent. What is most intriguing is that, across the vast Eurasian expanse, from Iceland to Japan, these daimons seem to resemble one another. These similarities can be attributed to two principal dynamics.

The first and most obvious is that, following the Alexandrian Conquest of the 4th century BCE, the overland Silk Road became an information superhighway for daimonological traditions. Here, the spread of daimonological lore generally occurred independent of any direct influence from any established religion, the reason being that daimons have always travelled more lightly than gods. Here I am not speaking of agency and mobility on the part of the daimons themselves, but rather of the movements and activities of the humans offering or seeking benefits or relief from them. Manipulating or transacting with daimons has never required the support of a sophisticated belief system or priesthood: what is essential is that the techniques employed be effective. Ritual gestures, speech acts without semantic content (ie, spells), mute power substances (crystals, botanicals, animal parts) and man-made devices (amulets, etc) are what human specialists have been offering their clientele for millennia, and the Silk Road market towns were daimonological changing houses where soldiers, sailors, merchants, monks and magicians transacted in specialised services, devices and expertise.

In some cases, we see a daimon’s original name being retained in a transplanted foreign setting, as shown in two texts from the 5th to 6th century CE, from southern China and northern Afghanistan, both of which make mention of South Asia’s rakshasas (‘guardians’). The first, the already mentioned Taoist Book of Divine Incantations, ranks its luoshas (the Chinese transcription of rakshasas) together with a host of Indigenous Chinese demons. Discovered 4,000 kilometres away, a Manichean amulet carries an inscription that classes rakshasas and yakshas together with the Iranian demons called peris and drujs, as well as ‘idols of darkness and spirits of evil’. These, as the amulet text reads, will be driven away through the power of the Lord Jesus Christ, the angels Michael, Sera’el, Raphael, Gabriel and others.

Female daimons who threaten human trespassers are won over by a hero, to whom they offer their bodies

A principal port for maritime trade between the Mediterranean world and South and East Asia, Mantai on the northwest coast of Sri Lanka was the venue for an astonishing case of daimonological exchange, in this case of an entire mythic complex. It was here that a c6th-century Buddhist monk named Mahanama authored the Mahavamsa, the island’s ‘Great Chronicle’. Its sixth chapter concerns an Indian prince named Vijaya who, shipwrecked there with his men, sends a scouting party to explore the island’s interior. They first meet the god Vishnu in disguise, who gives them protective threads to wear on their bodies. They then follow a she-dog that leads them to a pond, where they spy a female devata named Kuvanna (‘Ugly’), disguised as a Buddhist nun, spinning thread at the foot of a tree. The men are quickly trapped by her, who intends to eat them, but is unable to do so because of the amulets they are wearing. Then comes Vijaya who, sizing up the situation, threatens to slay the yakshi unless she releases his men. This she does, after which she offers everyone a great feast, and then, assuming the form of a beautiful 16-year-old maiden, takes the prince to her splendid bed. That same night, she instructs Vijaya on how to defeat the yaksha host controlling the island. She would later be slain by the yakshas for her betrayal.

For anyone familiar with Homer’s Odyssey, this episode is transparently identical to that of the encounter between the hero Ulysses and the female daimon Circe, a nymph whose handmaidens are described as ‘children are they of the springs and groves, and of the sacred rivers that flow forth to the sea’. Shipwrecked on her island, Ulysses sends out a party of scouts who come upon Circe’s hilltop hall, encircled by wolves and lions who behave like dogs because of a drug she had given them. Circe is weaving a great tapestry when the men arrive. She offers them hospitality, but the food she gives them contains a drug that transforms them into swine, which she imprisons in her pigsties. Alerted to their plight, Ulysses makes his way there, but en route meets the god Hermes who gives him a counter-poison to Circe’s evil drugs. Ulysses overpowers Circe and threatens to slay her unless she releases his men and restore them to human form. This she does, following which she offers everyone a great feast, and takes Ulysses to her beautiful bed. A year later, when she sends him on his way, Circe offers the hero essential guidance on how to continue his odyssey homeward.

Some 1,300 years and worlds apart, the two stories are virtually identical. Female daimons who first threaten the humans who trespass on their sanctuaries are won over by a hero, to whom they offer their bodies and their mercy. Carried on the winds of trade, a dire yet seductive nymph of ancient Greek epic was transformed, more than 1,000 years later, into a South Asian yakshi.

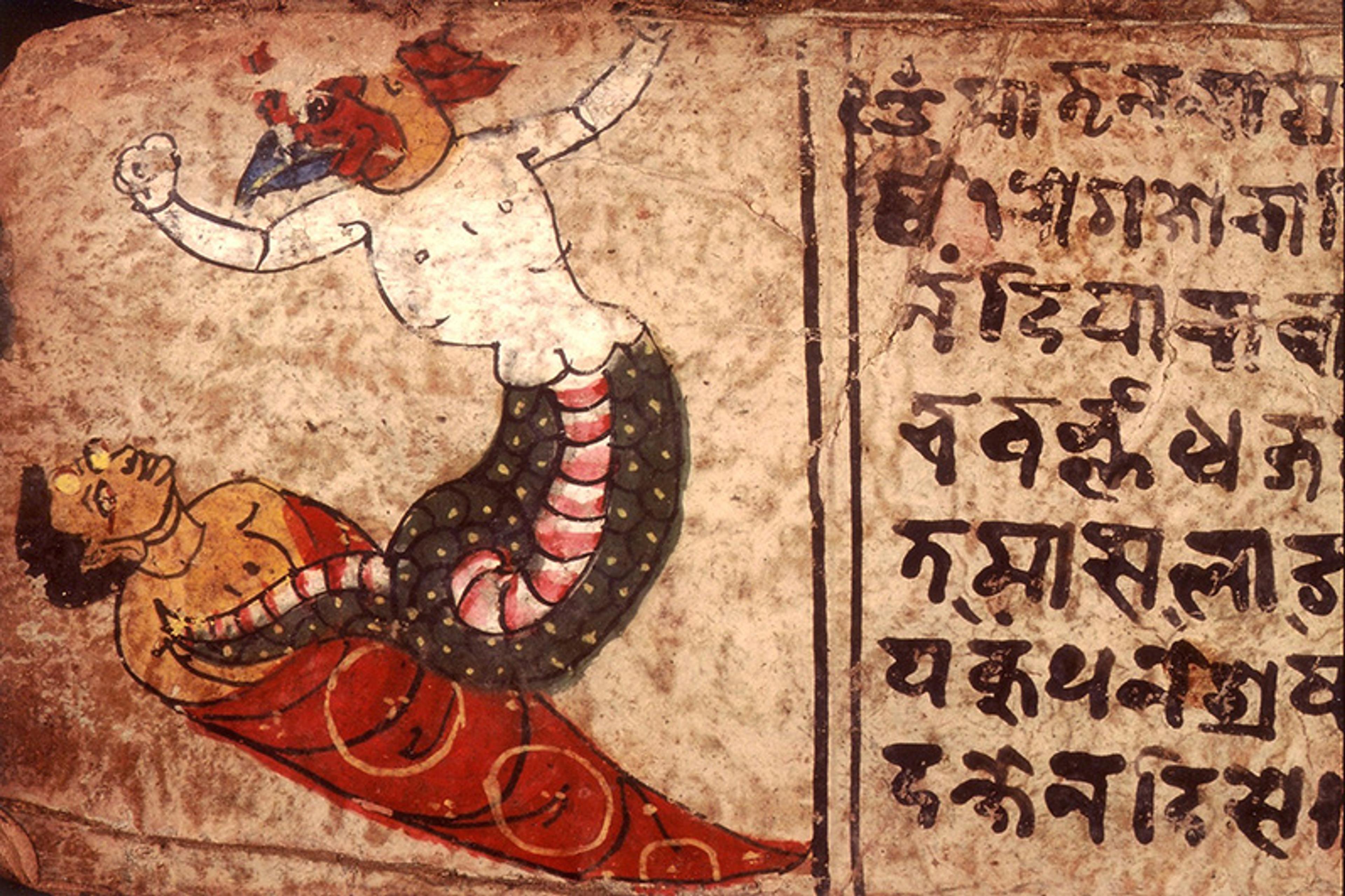

Carried along these same trade routes, mirror divination is a daimonological technology attested from North Africa to China. First mentioned in a c3rd-century CE Egyptian manuscript, the practice has always involved a single device and three actors: a human child, a human adult and a daimon. In the role of medium, the child is made to gaze into a reflective surface – a mirror, a bowl of water with oil floating on its surface, the polished blade of a weapon, etc – in which a daimon will appear. The adult at whose knees the child is sitting then utters a spell to bring the daimon into the device. He transmits to the daimon a set of questions about some present or future event, which the daimon answers through the child medium.

This technique spread quickly, appearing in both a Zoroastrian inscription from the 3rd century CE and in Jewish Talmudic sources from Sasanian Persia; in several 7th- to 12th-century Hindu, Buddhist, Jain and Taoist texts from India, China, Japan and Tibet; in the Policraticus (1159) by the English cleric John of Salisbury; and in medieval and modern-day Jewish, Muslim and Ethiopic sources from North Africa. The instructions found in a work titled the ‘Secret Rites’, an early 8th-century Chinese translation of a Sanskrit work, are virtually identical to those given in the 3rd-century Egyptian manuscript:

In front of an icon of the Immovable One [the Buddhist god Acala], let the officiant cleanse the ground and burn Parthian incense. Let him then take a mirror, place it over the heart [of the icon], and continue reciting the spell. Have a young boy or girl look into the mirror. When you ask what they see, the child will immediately tell you all you want to know.

– from Chinese Magical Medicine (2002) by Michael Strickmann

A most remarkable example of daimonological transmission across the entire Eurasian expanse concerns geothermal eruptions: boiling mineral springs, gas vents, volcanos, petroleum seepage, and the like. So it is that we find a virtually identical set of instructions for the ‘capture’ of mercury in three alchemical works. The c800-1000 CE Syriac version of the Treatise of Zosimus of Panopolis provides the following information:

In the furthest region of the West, where tin [zws, literally ‘Zeus’] is located, there is a spring of water that gushes out and pulls Zeus up like water. When the inhabitants of this region see that he is ready to overflow out of the spring, they have a virgin girl of outstanding beauty stand naked in front of him; she stands in a depression, in front of a deep hole in the field, so that he lusts after the beauty of the young girl; for he rushes upon her in a leap with the desire to take possession of her. But she is accustomed to running quickly, and there are young people standing next to her bearing axes in their hands. As soon as they see him draw near to the virgin girl, they beat and cut him; and he goes his way into that deep hole, and he congeals by himself and hardens. They cut this zws into pieces and make use of it.

Some 200 to 400 years later, the Sanskrit-language Rasaprakashasudhakara (‘Ambrosial Vessel of the Light of the Essential Elements’) by Yashodhara Bhatta provides similar instructions:

West of the Himalaya there is a beautiful peak named ‘Lord of the Hills’. Close by that peak, ‘Champion Mercury’ dwells in bodily form inside a perfectly rounded well. A beautiful, well-adorned young maiden mounted upon the finest of horses once came there. Looking down into the well, she then very speedily turned back. Most excellent Mercury rushed after her and fell to the earth in the four directions. Nowadays there is a perfectly circular field, which, stirred up by Mercury at that time, is evenly spread out for 12 yojanas in every direction around the well. Sublimated in a sublimation apparatus, the clay [ie, mercury ore] of that field is truly a disease-killing agent.

Less than a century later in China, Zhu Derun’s Cun fuzhai wenji (‘Collected Works on Preserving, Restoring, and Purifying’, 1347) relates that:

Their country lies in the region where the sun goes down … There is in this country a sea of quicksilver, spanning about 40 to 50 li in circumference. The way in which the inhabitants extract [the quicksilver is the following]: first they dig several tens of well shafts at a distance of 10 li from the shore, and after that they dispatch strong men [to that place] on horses that are so light-footed that they can keep up with a flying falcon. The men and the horses are all covered in gold leaf and ride abreast in tight formation skirting along the meanders of the sea’s shoreline. When the sun glints off the gold, [it emits] a dazzling brilliance; then the quicksilver boils up like a tidal wave and comes forth, as if it were intending to cling fast [to the gold leaf] with the strength of a viscous glue. Thereupon, the men immediately turn their horses around and ride off with the greatest of speed, and the quicksilver pursues them. Were they to move only slightly more slowly, then the quicksilver would strike and drown them. By the time the men and horses have raced back, the quicksilver’s strength has receded, and its vigour diminished. As they retreat further back to the well shafts, the quicksilver trickles and accumulates therein. Then the inhabitants immediately fetch it out. They boil it down with aromatic herbs, such that it all turns into fine silver.

In all three of these sources, mercury is portrayed as a daimon that rushes out of its natural habitat, its ‘well’, under the impulse of lust or rage, to pursue human trespassers. It is only after it has been neutralised that it becomes an inert mineral, the quicksilver used in alchemical reactions. These accounts are in fact variations on a far more widespread mytheme, which brings us to the second explanation – far more ancient than the first – for the striking similarities between the daimons of Eurasia. This is the concept of monogenesis, of a single common ancestor for an extensive corpus of myths. In this case, that mythology tracks with the languages of the Indo-European language family, whose members range from the ancient Sanskrit, Latin, Greek, Celtic and Slavic to the modern Romance, Germanic and Indic languages.

Moving deeper into Eurasia, they carried with them a ‘proto-Indo-European’ mythology of daimons

As the argument goes, the vocabularies of these member languages are similar because they can all be traced back to an ancestral tongue spoken more than 6,000 years ago by peoples living in the Caucasus region. Then, as these peoples migrated out into the Asian and European continents over the centuries and millennia, they carried with them their ‘proto-Indo-European’ language, which was gradually altered through the influence of the languages of the populations with which they came into contact. This is why, for example, the English word ‘mother’ closely resembles but is not identical to the Mutter of modern German, the mater/meter of Latin and Greek, the matar of Sanskrit and ancient Iranian, the madre of Spanish and Italian, the mathair of Irish, the mati of Serbo-Croatian and so forth.

Languages are vehicles for human thought, culture, imagination and practice, and so it follows that, when the speakers of the ancestral tongue moved deeper and deeper into Eurasia, they also carried with them a ‘proto-Indo-European’ mythology, including a mythology of daimons. A cluster of those myths concern various sorts of geothermal eruptions. Attested in Sanskrit and ancient Iranian sources going back to at least 1500 BCE, and found in ancient, medieval and modern accounts from Rome to Ireland, France, Greece, Turkey, England, Pakistan and Azerbaijan, these share all or most of the same complex of themes:

A subterranean daimon (1) is embodied as a volatile igneous being immersed in a body of living water (2). He is frequently associated with horses (3). He is roused to action by a provocative act (4) committed by a man (or men) or a woman (5) who approach(es) or trespass(es) his abode. After erupting from his basin, well or depths (6), the daimon in his caustic, fiery, superheated or volatile form (7) pursues the trespasser(s), blinding, maiming, drowning and in some cases killing them (8) – and sometimes flooding or laying waste to an entire region in the process. The advancing igneous fluid daimon may be controlled or diverted through channels or trenches (9), which in some cases redirect him back to his source.

What do these data tell us? For several thousand years, human actors have been carrying their inner daimons with them as they moved across the Eurasian landmass, recognising the daimons of ancient landscapes as they came upon previously unknown places. When the gods and goddesses of the great religions first emerged, they came into a world already populated with daimons. These are still with us, morphing into new forms in digital environments: mailer-daemons, internet trolls, so many ghosts in the machine…