In 1970, a 57-year-old man died of heart disease at his home in Queens, New York. Fredric Kurzweil, a gifted pianist and conductor, was born Jewish in Vienna in 1912. When the Nazis entered Austria in 1938, an American benefactor sponsored Fred’s immigration to the United States and saved his life. He eventually became a music professor and conductor for choirs and orchestras around the US. Fred took almost nothing with him when he fled Europe – but, in the US, he saved everything. He saved official documents about his life, lectures, notes, programmes, newspaper clippings related to his work, letters he wrote and letters he received, and personal journals.

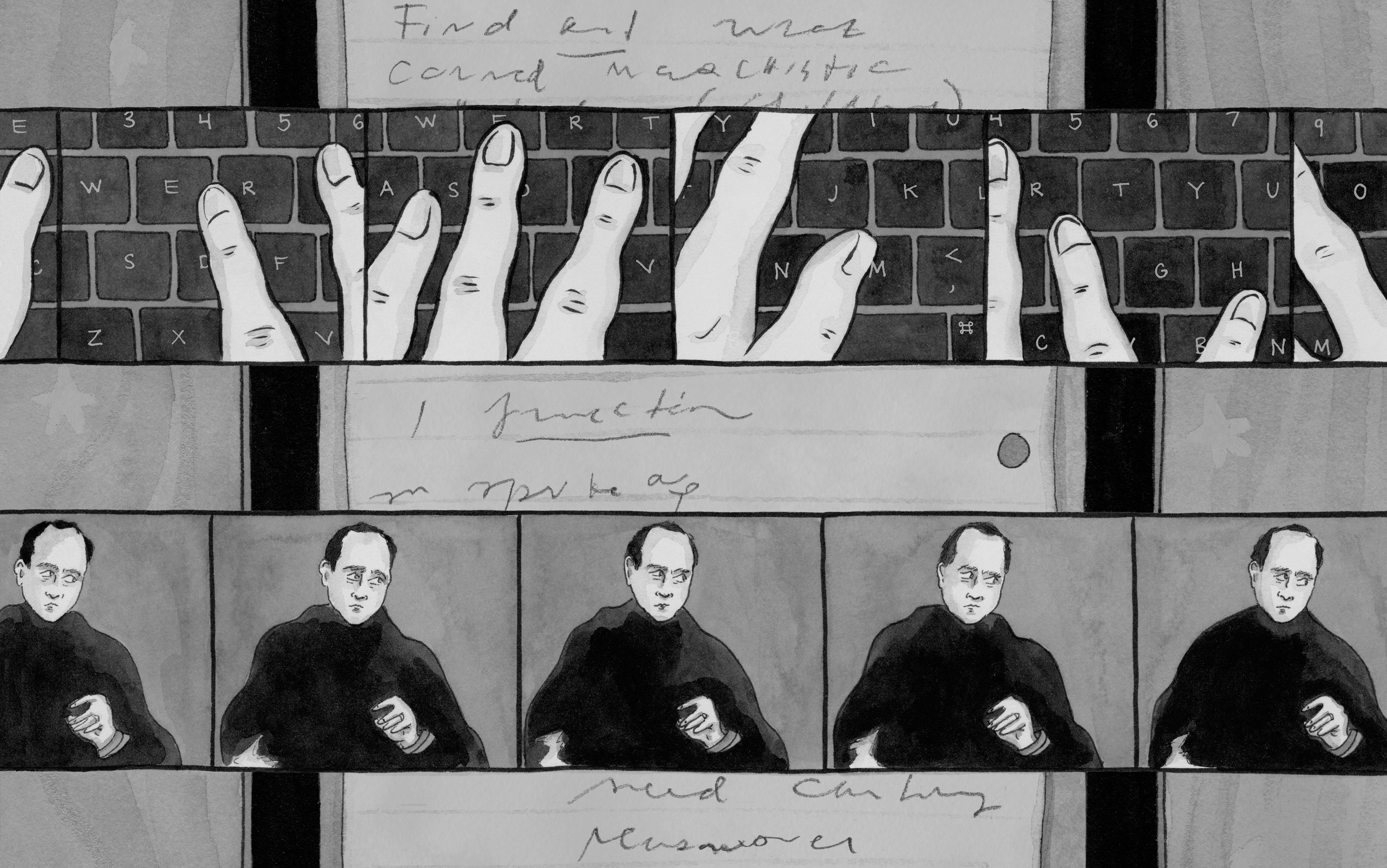

For 50 years after Fred died, his son, Ray, kept these records in a storage unit. In 2018, Ray worked with his daughter, Amy, to digitise all the original writing from his father. He fed that digitised writing to an algorithm and built a chatbot that simulated what it was like to have a conversation with the father he missed and lost too soon. This chatbot was selective, meaning that it responded to questions with sentences that Fred actually wrote at some point in his life. Through this chatbot, Ray was able to converse with a representation of his father, in a way that felt, Ray said: ‘like talking to him.’ And Amy, who co-wrote this essay and was born after Fred died, was able to stage a conversation with an ancestor she had never met.

‘Fredbot’ is one example of a technology known as chatbots of the dead, chatbots designed to speak in the voice of specific deceased people. Other examples are plentiful: in 2016, Eugenia Kuyda built a chatbot from the text messages of her friend Roman Mazurenko, who was killed in a traffic accident. The first Roman Bot, like Fredbot, was selective, but later versions were generative, meaning they generated novel responses that reflected Mazurenko’s voice. In 2020, the musician and artist Laurie Anderson used a corpus of writing and lyrics from her late husband, Velvet Underground’s co-founder Lou Reed, to create a generative program she interacted with as a creative collaborator. And in 2021, the journalist James Vlahos launched HereAfter AI, an app anyone can use to create interactive chatbots, called ‘life story avatars’, that are based on loved ones’ memories. Today, enterprises in the business of ‘reinventing remembrance’ abound: Life Story AI, Project Infinite Life, Project December – the list goes on.

These apps and algorithms are part of a growing class of technologies that marry artificial intelligence (AI) with the data that people leave behind. These technologies will become more sophisticated and accessible as the parameters and popularity of large language models increase and as personal data expands into the seeming permanence of the cloud. To some, chatbots of the dead are useful tools that can help us grieve, remember, and reflect on those we’ve lost. To others, they are dehumanising technologies that conjure a dystopian world. They raise ethical questions about consent, ownership, memory and historical accuracy: who should be allowed to create, control or profit from these representations? How do we understand chatbots that seem to misrepresent the past? But for us, the deepest concerns relate to how these bots might affect our relationship to the dead. Are they artificial replacements that merely paper over our grief? Or is there something distinctively valuable about chatting with a simulation of the dead?

The bonds we form with others infuse our lives with shared meaning and warmth, but these connections are threatened by time and the rupture of death. Profound loss is inevitable. This is why all human cultures have developed rituals, stories and other resources for dealing with the death of loved ones. In Book 11 of Homer’s Odyssey, also known as the Nekyia (or Book of the Dead), Odysseus journeys to the underworld and finds his dead mother, Anticlea, who has become a shade – a spirit he cannot embrace.

The ancient Egyptians’ own Book of the Dead – a collection of texts originally written on papyrus scrolls and the walls of tombs – offers incantations to guide lost souls safely into the afterlife where they might be granted immortality. Alongside such ancient stories and spells are ongoing rituals that engage the dead. In some Asian cultures, the gates of the underworld are said to open during ‘Ghost Month’, and the spirits of dead ancestors freely wander the human realm. Likewise, the Mexican Dia de Los Muertos is a time of remembrance and celebration when the living and dead can commune. Other rituals are less public. In Jewish culture, sitting shiva – which takes place in the seven days immediately after the death of a loved one – facilitates a structured space for coming together around the memory of the deceased. In Japanese culture, sacred objects like the butsudan, a small domestic Buddhist shrine for honouring deceased family members, support continuing bonds with dead ancestors.

These beliefs and cultural practices offer hope that the living might one day fulfil their desire to commune with the dead. They sustain people through grief by promoting the sense that the human community transcends loss, and that love is not destroyed as long as memory remains.

When someone dies, the rational person is expected to close the curtain on that relationship and move on

But in the industrialised West, communities of support are collapsing. Our spiritual institutions, practices and beliefs have been denuded by centuries of disenchantment. This may suggest that technological modernity, with its commitment to scientific rationalism, is to blame for the Western world’s often-impoverished relationship to death.

To be rational in the industrialised West is to grant primacy to what can be seen, touched and measured. When someone dies, the rational person is expected to close the curtain on that relationship and move on. Instead of offering new spiritual resources, our technocultures seem to provide us with a vast array of ingenious instruments to help us turn away from death: we have medicine to postpone, entertainment to soothe, drugs to stupefy, and other technologies to help us avoid and ignore. The average person is at once inundated with stylised images of people dying while being sequestered from real, meaningful experiences with death. All the while, the technological advances that saturate our lives with increasing wealth and power whisper of a way beyond death, of new eschatologies of mechanical transcendence.

Yet, for all its dynamism, this technological ingenuity has not quelled the suspicion that there are no technical solutions to spiritual problems. It is often said that, rather than providing resources that meet our needs, our instruments merely help us deny the reality of death. To some, these technologies are nothing more than embalming tools, made to mask the inevitable pain of profound loss. And among these many tools, what could be more pernicious than a chatbot that speaks in the voice of those who are, in reality, gone forever?

Since its inception, chatbot technology has been associated with illusion, and subject to suspicion. One of the first and most well-known chatbots, ELIZA, was created in the 1960s by the MIT professor Joseph Weizenbaum, a computer pioneer-turned-critic who later decried AI as an ‘index of the insanity of our world’. ELIZA was designed to imitate a psychotherapist, employing keyword detection and preprogrammed rules to ask users basic questions that prompted verbalisation and reflection. Although rudimentary by today’s standards, people found ELIZA compelling. When Weizenbaum’s secretary asked for alone time with the chatbot, the professor took it as evidence that she erroneously thought the machine had a mind. As a result, Weizenbaum came to believe that even simple chatbots like ELIZA ‘could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people.’ Today, chatbots employ machine learning rather than preprogrammed rules and can hold sophisticated conversations by making inferences, responding to questions, tracking context and conversational presuppositions, and more. To a much greater degree than ELIZA, contemporary chatbots can produce a compelling conversational experience similar to a human interlocutor.

Although chatbots have been around for a long time, chatbots of the dead are a relatively new innovation made possible by recent advances in programming techniques and the proliferation of personal data. On a basic level, these chatbots are created by combining machine learning with personal writing, such as text messages, emails, letters and journals, which reflect a person’s distinctive diction, syntax, attitudes and quirks. There are various ways this combination can be achieved. One resource-intensive method involves creating a new chatbot by training a language model on someone’s personal writing. A technically simpler method involves instructing a pretrained chatbot, like ChatGPT, to utilise personal data that is inserted into the context window of a conversation. Both methods enable a chatbot to speak in ways that resemble a dead person by ‘selectively’ outputting statements the person actually wrote, ‘generatively’ producing novel statements that bear some resemblance to statements the person actually wrote, or some combination of both.

A chatbot of the dead that’s monetised or gamified could be dangerous in the hands of an unscrupulous corporation

Chatbots can be used on their own or combined with other forms of AI, such as voice cloning and deepfakes, to create interactive representations of the dead. When provided with the right data, many companies and platforms now have the technical capacity to generate a conversational AI version of your deceased loved one. In the future, these chatbots will likely become more common and sophisticated, involving much more than just text. Like human mediums and Ouija boards, these bots appear to meet one of our deepest desires: to speak with the dead once again.

Many critics view this technological endeavour as an especially abject form of death denial. A common objection to these bots is that emotionally vulnerable users may become so invested in their interactions that they will conflate their chatbot with the deceased person, or lose sight of the fact that the person is gone. As the philosopher Patrick Stokes puts it in Digital Souls (2021), we may ‘become so used to avatars of the dead that we accept and treat them as if they’re the dead themselves.’ This sort of worry suggests, as Weizenbaum feared, that the salutary potential of chatbots is based in delusional thinking.

Another worry relates to chatbots’ lack of inner lives. Critics, like the philosopher Shannon Vallor in The AI Mirror (2024), argue that there is something defective about emotional bonds with entities that cannot reciprocate affection or interest, about love that is kept alive by ‘the economic rationality of exchange’ rather than a more precarious ‘union of loving feeling and action’. And these emotionally one-sided relationships create a risk of over-reliance, social isolation and exploitation. This risk is especially stark given that chatbots of the dead may be produced by companies with a financial incentive to manipulate users and maximise engagement. A chatbot of the dead that is highly monetised (unlock your chatbot’s ‘caring’ traits for a small fee!) or gamified (chat every day to level up!) could be a dangerous tool in the hands of an unscrupulous corporation.

These types of critiques often implicitly assume that the purpose of chatbots of the dead is to function as a kind of stand-in for a lost loved one, an ersatz companion of sorts. This use suggests that chatbots should be designed to be as realistic and fully formed as possible. And from this vantage point, there are two possible problems: either chatbots cannot live up to this standard, and therefore they are deceptive and defective, or they can live up to this standard, and therefore they will confuse, isolate or exploit those who use them.

But this implicit assumption is wrong. Chatbots of the dead should not be used as stand-ins or companions. Nor should they be built to be as realistic and fully formed as possible. Instead, chatbots of the dead should be made to serve a purpose that is more familiar and more complex, a purpose that can help us transcend our mortal condition, not through technological resurrection, but through imagination.

Any griever, or any student of history, knows that relationships don’t end neatly with death; memories, imaginings, questions and answers continue to churn in the minds of the living, aided by artefacts and shared community. The secular space where we allow this reality to flourish is the arts.

‘Everything is as it should be, nothing will ever change, nobody will ever die,’ writes Vladimir Nabokov in his memoir, Speak, Memory (1951). Conjuring memories of childhood for the reader, he evokes a vivid sensory picture:

I see again my schoolroom in Vyra, the blue roses of the wallpaper, the open window. Its reflection fills the oval mirror above the leathern couch where my uncle sits, gloating over a tattered book. A sense of security, of well-being, of summer warmth pervades my memory … The mirror brims with brightness; a bumblebee has entered the room and bumps against the ceiling.

This passage may not denote a specific event, bumblebee or book. More likely, this is a composite scene staged from different impressions. When Nabokov describes his uncle as ‘gloating’ over a book, he arrives at this description from childhood memories filtered through adult inferences – ‘gloating’ is not typically a child’s concept. Memory is a space to grasp meaning through a gauze of impressionistic details, and the arts are spaces where this stippled portrait of past life can live on.

We save these kinds of artefacts to nurture our imagination of the past and our ancestors

We live our lives through a multitude of meaningful fictions, personal memory being one of them. This form of memory is often built, like Nabokov’s scene, from a composition of impressions – blue roses on wallpaper, a bee, a book, an expression on a family member’s face – that we stitch into a narrative when recounting scenes from our lives. This stitching-together constitutes a kind of fiction that is not opposed to truth. In Mimesis as Make-Believe (1990), the philosopher Kendall Walton describes fiction as that which ‘is to be imagined’. The passage above prescribes that the reader imagine Nabokov’s room in Vyra. This room is thus part of a fictional world. Although a bookstore might classify Speak, Memory as ‘literary nonfiction’, the world it prescribes is, in Walton’s sense, fiction, just a different kind of fiction than what is prescribed by Nabokov’s novel Pale Fire (1962). Speak, Memory makes extensive use of imagination to make the reader feel the work’s proposition: that the author’s childhood was tinged with warmth and sadness. According to Walton’s framework, the passage from Speak, Memory and others like it function as ‘props’ that ‘mandate’ and ‘prompt’ imaginings. These imaginings can be described in terms of propositions (eg, a bumblebee bumps against the ceiling) that are true within a fictional world – ie, a world that a reader of Speak, Memory is to imagine. By inhabiting this kind of fictional world, we can seek truth about our past and our relationships. Art formalises these fictional worlds and the quests for truth within them.

Salvaged artefacts, like diaries and letters, can also serve our quests. When Amy reads a letter from 1967, written by her grandmother to her grandfather away on business, she is transported in time, place and perspective. She imagines her grandmother Hannah writing the letter and her grandfather Fredric receiving it. She imagines how her grandfather feels learning about his wife’s 10 cent raise, the look on his face reading about how their daughter has grown. References are filled in with imagination, based on inference; the value of 10 cents in 1967, the age of Amy’s aunt. The letter is a historical artefact that serves as a Waltonian prop, determining content in the fictional world Amy constructs as she imagines the lives of her grandparents. It furthermore serves as a Waltonian prompt, prompting Amy to imagine that world and other related memories. We save these kinds of artefacts to nurture our imagination of the past and our ancestors. The more examples of ancestral voices we survey, the more enriched is our sense of their identities, the more insight we gain into our families and ourselves.

But even without tangible props or prompts, like photos and letters, we can nonetheless imagine based on looser connections. A vague story told in passing about a great-great-grandparent may serve as a prop, prompting a vision of the past – if the listener has interest in imagining it. A hat from the 1890s may prompt us to imagine an ancestor wearing it. The more detailed, specific and multi-modal our prompts and props, the closer the imagined representation of a past person may be to the once-living person.

But a representation will always remain a representation – regardless of its accuracy.

Like memoirs, photographs, letters, hats and oral histories, chatbots of the dead can serve the manifold goals of our memory quests, giving context to our lives, relationships and identities as they help us forge connections across time. They can function as Waltonian props that help generate fictional worlds and prompt receptive users to enter these worlds. Therein, we can explore and continue the relationships that matter to us. Because chatbots are not people but props that help us generate imaginary conversations, the user’s interlocutor – a character based on the deceased – does not exist independently of the conversation. Chatbot users create their imaginary interlocutors through their interactions with their prop chatbots. In this way, chatbots bestow a special form of creative agency upon users, wherein users play an active role in creating fictional worlds and the fictional characters within them. Talking to a chatbot is thus like the art of improvisation. The chatbot user is simultaneously a creative artist and a receptive viewer who directs and is directed towards meaning, insight or amusement.

The complexity of these interactions is not unique. Humans are adept at roleplay: we joke, we pretend, we play. For that reason alone, Weizenbaum’s assessment of his secretary was patronising. It is uncharitable to the woman’s intelligence to assume she was, as Weizenbaum feared, delusionally attributing agency to the machine when she sought alone time with ELIZA. More likely, she was using ELIZA as it was designed: to imaginatively roleplay therapy. ELIZA was not a therapist; it was a prop, a partial entity that needed a user to animate it.

This imaginative potential is obscured when chatbots of the dead are envisioned as flimsy stand-ins for deceased loved ones. This vision is common in science fiction, like the Black Mirror episode ‘Be Right Back’ (2013) in which a grieving woman becomes attached to an AI that replaces her dead partner. And this stand-in vision is accepted by critics and also many users who, like the journalist Cody Delistraty in The Grief Cure (2024), set out to ‘re-create’ their loved ones ‘with as much fidelity as possible,’ only to feel ‘broken’ when ‘that alternate reality bursts’ and their loved one ‘dies once more’.

Chatbots of the dead, like participatory theatre, allow the audience to participate in fictional worlds

This is the wrong way to view chatbots of the dead. Instead, the potential of these technologies would be better understood if they were thought of more like artworks – or, rather, like theatrical performances. Engaging with a chatbot is a lot like attending a participatory theatre performance. In these performances, audience members play active roles in the story. Early forms of participatory theatre include performances at Dionysian festivals or medieval mystery plays. More modern examples include Bertolt Brecht’s attempts to break the ‘fourth wall’ during his plays, and the immersive theatrical performances where audiences freely explore the space of the theatre, interacting with actors.

A chatbot based on someone’s data is like an improv actor who has studied a backstory or character sketch in order to performatively represent a character based on that person, like a Civil War soldier at a historical reenactment, an Elvis impersonator, or King Pentheus in Dionysus in 69 (1969), the participatory rendition of Euripides’ play The Bacchae. Chatbots of the dead, like participatory theatre, allow the audience to directly participate in these fictional worlds, thereby becoming imaginatively acquainted with the real person to whom the character corresponds.

This theatre analogy is not perfect. Unlike human actors, chatbots are not physically present. They do not make conscious choices about how to portray characters or co-construct meaning with their audience. Nevertheless, this framework is useful because it clarifies and accentuates the relation between chatbots and the deceased. Actors are neither identical to, nor replacements for, the real people they represent; instead, they convey information about them and a felt sense of their particularities and complexities.

A discerning user should view chatbots similarly. Depending on how they are designed, chatbots can represent a person in many ways. The assumption that a chatbot delivers – or seeks to deliver – an authoritative replication of a deceased person makes as much sense as the assumption that an actor’s portrayal of a historical figure in a drama represents the sole faithful depiction of that figure. Just as the inspiration for a historical character may come from various sources, our personal data flows from different aspects of our identities. People do not really speak in a single voice: most people are different on social media than they are in text messages, for example. There is no one way to design a chatbot ‘actor’ because there is no best or definitive perspective on a person, no best or definitive fictional world in which to encounter someone’s legacy. There are countless useful, informative, intriguing, funny, strange, beautiful perspectives that a chatbot ‘actor’ might stage, just as there are countless ways a human actor can play a role, a writer compose a memoir, or a portraitist paint a picture.

Let’s bring this vision to life with several imaginative possibilities. Imagine that you collaborate with engineers to create a chatbot of your deceased grandfather. You decide to build a selective chatbot to memorialise him via sentences he actually wrote or said. But you want the conversations to flow smoothly, so you include some generative functionality. You embark on the laborious task of deciding which salvaged writing to include in the dataset. It quickly becomes clear that sentences from cover letters are written in a professional voice that differs from the intimate voice of family letters. You also have audio recordings, but your grandfather’s spoken voice is different from the way he writes – a person’s multitudes are not easily sortable into clear categories.

And so, the builder of this chatbot is forced to ask difficult questions about the deceased that call for care and attention: how do I want to remember them? How should a person be remembered? The deliberative effort that goes into building a chatbot highlights that the end product is a representation, inflected with the creator’s choices and perspectives. Ultimately, you decide you cherish your grandfather’s sense of humour, and you want your children to know about his experience fighting in the Second World War. You design two bots, trained on different material, to performatively present these two sides of your grandfather. The history bot also serves as a navigator of your family archive, linking to scans of primary documents.

Imagine another possibility: you’ve recently lost your partner in a tragic accident. Your loved ones have returned to their normal routines, but you’re still deep in mourning and seeking guidance and support as you plan for the future. Your partner is vivid in your mind, and it’s disorienting to live in a world in which their absence is accepted. So, you allow a tech company to use all available data from your partner to train a generative bot – you want it to be as expansive and conversant as possible. And here’s where this story diverges from Black Mirror. The tech company’s platform offers you a frame around the conversations: the bot periodically ‘breaks character’ to check in, prompting reflection on how the representation aligns with your memory, your emotional state, and the insights you’re gaining, helping you make adjustments to the bot as necessary. Using the bot becomes a process of shaping your grief and the representation. And, since you’re continuously reminded of the frame around the representation, you don’t see it as a replacement.

A chatbot could play the role of a museum curator, speaking knowledgeably about a person’s archives

Imagine now that you are an adult who lost both your parents when you were younger. You have a family of your own, and lately you find yourself wondering about your parents’ choices. You’re interested in the wisdom of their shared perspective. Why did they make certain decisions for your family? So, you build a generative chatbot that is informed by data relating to both your parents’ thoughts on family and parenting. This includes excerpts from their writings, memories of things they said, along with passages from books and other media they valued that relates to these themes. You engage with this chatbot as a unique intelligence; it does not represent an individual, but neither is it a generic intelligence, like ChatGPT. It represents a specific collective wisdom.

These are just examples. The creative design possibilities are immense and must be explored in artistic practice. Practitioners should look to the arts and other cultural resources that help people deal with loss and memorialise history. For example, a chatbot could be designed to speak as a spiritual medium channelling the deceased from a spiritual realm in order to emphasise the separation of death and impart a sense of mysticism to the imaginative experience. Or chatbots could be designed to employ Brecht’s ‘alienation effect’, which involves acting techniques designed to inhibit immersion and promote aesthetic distance between an audience and the events on stage, making room for reflection. Alienation techniques include character breaks and metatextual discussion, as in the example involving a deceased partner. In this vein, a chatbot could be designed to play the role of a museum curator, speaking knowledgeably about the person they are representing and their archives.

Chatbots of public figures might inspire stylised voices of the deceased, eg, caricatures that, like Elvis impersonators, magnify idiosyncratic qualities for the purpose of parody, satire or celebration. A classroom might create a bot based on the narrator from a memoir; for example, students could continue a conversation with Nabokov after Speak, Memory ends. You might create a bot trained on your childhood journals, so you can converse with your past self. An abusive parent might be represented at their most rageful to help process childhood trauma in a therapy session. An anxious person might be represented in a way that allows users to read their worried thoughts to promote empathy and understanding. A chatbot might be trained on all available family records to speak in the voice of your ancestors. Another might be trained on all the known writing from a particular ancient village. Yet another might be trained on all the works of a prolific lost writer: Plato, James Baldwin, Ursula K Le Guin, or a group of writers from a particular point in history: the Beats, the Transcendentalists, the members of OuLiPo. The possibilities are endless. This technology can help us appreciate the composite nature of the characters we imagine in fictional worlds and the different purposes remembrance might play in our lives.

If these examples sound like they require a lot of thought and labour on the part of the bot’s initiators, that’s because they do. Good artistic representations require creative work. And this creative work is valuable for its own sake. In fact, the work that goes into producing a chatbot – which should involve many artistic choices as well as reflective engagement with archives and memory – may be more meaningful than any finalised product. Just as participatory theatre de-emphasises a complete and polished production in favour of process and iteration, building a chatbot requires constant fine-tuning. Thus, performance and creative development are part of the same process.

There is, in a sense, no chatbot finalised product that stands apart from users’ creative input, since chatbots are props that can bring a fictional world to life only in participation with users and their improvisational choices. This is one reason why, although chatbots can help ease the burden of navigating and accessing archives, they do not shrink or replace those archives. It is also why we should be suspicious of technology companies that offer us easy, prefabricated, supposedly complete chatbots. We should instead seek technology that enables us to create and fine-tune our own chatbots – without requiring extensive technical expertise. There are no shortcuts to thoughtful representations. And we should not try to circumvent the valuable creative process.

This shift from chatbots as companions to tools of artistic remembrance deflates many common concerns. From this vantage point, we can see that chatbot ‘actors’ do not necessarily aim at realism. They cannot and will not capture a deceased person fully. They do not delude users into behaving as if the dead are still alive or believing that they are talking to a real person. On the contrary, they underscore absence in the real world by engaging the memory of the dead in imagined spaces. Moreover, concerns about one-sided relationships with chatbot ‘actors’ are misplaced, since the natural object of a user’s attachment is the deceased person, and by extension the characters that represent them, rather than the tools that generate those characters. These tools – particular chatbots on particular platforms with evolving data sets – will typically be interchangeable and ephemeral in a way that the dead person is not. If these tools are made to serve artistic goals, rather than commercial ones, the attachments they foster will be nourishing rather than addictive.

Some may fear the liberties AI will take with the legacies of the dead. To this we emphasise that these liberties are ours to authorise. Chatbots of the dead are creative representations that users should take an active role in shaping. Imagination is integral to all creative representations of the past because imagination is inextricable from memory and historical interpretation. We emphasise imagination not to abandon truth, but to show how truth can flow from our imaginations. We should judge AI representations by the same standards that we judge all truth-seeking artifice. An overly sentimentalised biopic may be worthy of the same critiques as a saccharine and evasive chatbot. Chatbots’ differing aesthetics will serve different purposes in our lives, from emotional release to therapeutic insight to intellectual enrichment to historical education. And like all aesthetic enterprises, the value of a chatbot is commensurate with the thought and effort – the creative choices – put into it by its authors.

Our framework points towards a future where our technocultural resources can be more than tawdry distractions. They might offer a way past our modern problems with death. Rather than instruments that help us deny loss, chatbots of the dead can be a resource for reflecting upon our own mortality and those we have lost. They can provide a felt sense of the human community that preceded us, and they can support, or even promote, the loving bonds that do not disappear in grief. Chatbots of the dead exist within the universal register of art, imagination and spirit. This register plays an ineliminable role in human flourishing, and we are optimistic that chatbot ‘actors’ can be conducive to a form of flourishing peculiarly suited to our age.

The view of chatbots outlined in this essay is not a panacea. Even if our vision were adopted and the necessary infrastructure for creative use were made available, there would still be opportunities for misuse and exploitation. Chatbots of the dead will surely attract technology companies with economic incentives that are at odds with both the interests of users and the artfulness we have envisioned. There is a risk that the artistic spaces we envision will be colonised by bland, addictive, prefabricated, highly monetised, gamified commercial products, which serve only to benumb us from our spiritual problems. But art and creative spaces have long been a source of resistance to the domineering forces in human life. Let us not abandon new technology to the flattening effects of narrow commercial interests. Rather, let us assert AI’s potential to further the spiritual mission of humanity’s irrepressible creativity, our duties to history and memory, and our quests for insight and connection.