On 16 November 1973, Joan Watts received a phone call that began in the worst possible way: ‘Are you sitting down?’ Her father, the English writer and philosopher Alan Watts, had died during the previous night, as a storm lashed his home in Marin County, California. His heart had failed at the age of just 58. Watts’s third wife, Mary Jane Yates King or ‘Jano’, blamed his experiments with breathing techniques intended to achieve samadhi, or absorptive contemplation: he had left his body, she thought, without knowing how to come back. Joan took a different view. Her father had become lost in work and alcohol. He had finally ‘had enough’, she concluded, and had ‘checked out’.

It seems fitting that, even in the manner of his dying, Watts should divide opinion. He frequently did so in life. Born in 1915, in Chislehurst in Kent, Watts moved to the United States with his first wife shortly before the outbreak of the Second World War. Living first in New York, he ended up making his home on the West Coast, where he joined the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder as a leading light of the 1960s counterculture.

Countless young Americans heard Watts speak, on campuses and on the radio, extolling the wisdom of the East and informing them in wry, patrician English that the ideals into which their parents and teachers had indoctrinated them were, by comparison, empty. Life did not have to be ‘about’ something or ‘going’ somewhere, any more than the point of playing or listening to a Bach prelude was to get to the end as quickly and efficiently as possible. One’s aim instead should be to tackle the monstrous case of mistaken identity from which so many modern Westerners suffered: each believing themselves to be a small, anxious self when underneath lay a glorious greater Self, entirely at one with the rest of reality.

To his detractors, Watts was an unlettered dilettante – he lacked an undergraduate degree – guilty of peddling a mash-up of Zen, Taoism and Vedānta to the unwary, throwing in psychotherapy, psychedelics and quantum physics for good measure. He lacked moral seriousness, too, preferring forms of religion that emphasised insight over conduct as a path to the divine. The result was a bleak contrast between Watts’s high talk of compassion and love and a series of affairs that, combined with his low view of fatherhood – ‘mow the lawn, play baseball with the children’ – helped to destroy his family.

The man himself gave as good as he got. Watts dismissed his academic critics as hopelessly out of touch with intellectual goings-on beyond the confines of their own institutions and networks. He wrote to the editors of Playboy magazine that:

Under the cover of lusty and curvaceous chicks (of whom I approve), and of silly bunnies (of whom I disapprove), you have turned Playboy into the most important philosophical periodical in this country … by comparison, the Journal of the American Philosophical Society is pedantic, boring and irrelevant.

But if a life philosophy may be judged by its fruits, Watts had become a poor advert for his own ideas by the early 1970s. Desperate and drinking heavily, he was capable of remaining lucid at the lectern but was exposed when he drifted off to sleep during the Q&A (devoted fans sometimes interpreted this as a silence wiser than words). And in the years after his death, several intellectual trends conspired to undermine much of what he had stood for. Edward Said’s Orientalism (1978) helped to kickstart decades of academic criticism of the damage wrought when skewed and self-interested Western views of ‘the East’ pass into global circulation. A year later, the equally influential social critic Christopher Lasch argued, in The Culture of Narcissism, that a vogue for ‘psychic self-improvement’ and ‘the wisdom of the East’ was a sign that Americans had given up on serious politics and social change, lapsing instead into self-indulgence.

Here was someone who understood, in a visceral way as a young man, the terror of loneliness and lack of meaning

Flares and campervans were soon being traded in for sensible alternatives, the ageing hippie became a stock comic character, and parodies proliferated of Yoda’s gnomic utterances in Star Wars (which owed much to George Lucas’s interest in Asian and world mythologies). Any hint of personal convenience in a philosophy that draws elements from far afield was always going to render it vulnerable, at some point, to charges of ‘cultural appropriation’: a notion that feels prudish and incoherent when applied to the serving of sushi on US college campuses but which has force when profound ideas and practices are taken and twisted without regard for those to whom they are sacred.

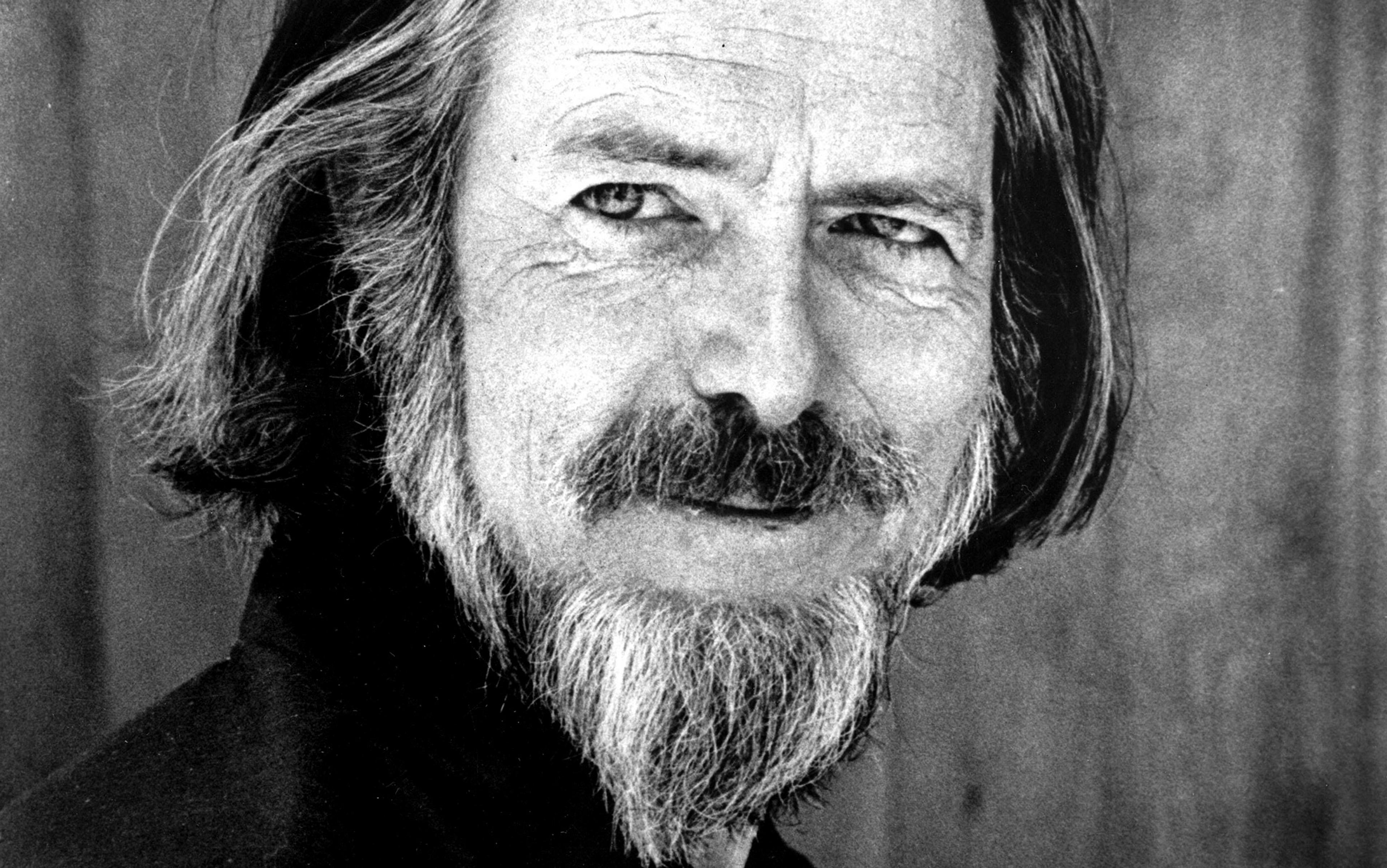

Alan Watts in 1964. Courtesy of Chapman University Special Collections

Those who treasured – and continue to treasure – Watts have felt equally strongly about the man and his legacies. Here was someone who understood, in a visceral way as a young man, the terror of loneliness and lack of meaning. With warmth, humour and an extraordinary gift for communicating complex ideas, Watts had shown people that the wrongness they sensed in life was not built into the universe. It was the outcome of degraded modern ways of living. The good news, as he preached it in person, in broadcasts and in his bestselling books, was that this fearfully bleak situation could be cured. There is no underestimating his posthumous ability to save or redeem lives, as Tim Lott revealed in his moving Aeon essay about Watts some years ago.

It is tempting to believe that the intellectual and cultural backlash against thinkers of the counterculture era like Watts has now peaked, and is being replaced by what the philosopher and cognitive scientist John Vervaeke calls the ‘meaning crisis’. From wellness and yoni eggs through to Jordan Peterson and a roster of new and often socially conservative Christian converts, we seem no less interested now than Watts in his day about how we might foster a society more in tune with natural and even cosmic realities. Watts himself remains an inspiration, enjoying a busy online afterlife thanks to the uploading of his talks as podcasts and YouTube videos. His gift for the pithy one-liner turns out to be perfect for the age of X/Twitter and Instagram. And his books, like The Wisdom of Insecurity (1951), still enjoy the status of classics.

Given the somewhat unexpected role of Christianity in this new moment, the time has come to include Watts’s much underrated stint as an Episcopal priest in our assessment of him. His view of Christianity’s potential in the modern West, and his cautions about the ways in which it can go wrong, feel as relevant and psychologically astute now as ever. As we negotiate religion in the 21st century, Watts can help us understand some of its great tensions: between pride and grace, insight and morality, spiritual renewal and nostalgia for an idealised Christian society of the past.

Watts’s experience of Christianity as a child was almost wholly negative. During his childhood in Chislehurst, he spent many a lonely night in bed, resisting sleep lest he die and find himself in heaven or hell – as pictured in Victorian and Edwardian hymns and described in lessons at school. Those hymns seem to have upset the young Watts, ill-equipped as he was to treat as anything other than very literal accounts of life after death phrases such as:

How sweet to rest

For ever on my Saviour’s breast.

And:

Prostrate before Thy throne to lie,

And gaze and gaze on Thee.

Only after discovering and practising Zen and yoga, thanks to a handful of friends and the bookshops of Camden Market in London, did Watts begin to taste for himself what he later called the ‘supreme identity’. In our imaginations, he argued, we are here while God or the good life is over there. The journey from here to there, we are told, consists of some combination of earnest striving and good behaviour. Drawing on Carl Jung, Zen, Taoism and Vedānta, Watts questioned the reality of this lonely, striving self. Let it go, he suggested, and you may glimpse a truer – supreme – identity that lies beneath it, and which the Upanishads capture in three words of Sanskrit: Tat tvam asi (‘You are that’). This deepest identity, a person’s soul or Self (ātman), is identical with the Absolute.

He was mesmerised by the ‘turn of a bird’s wing’ and ‘the kiss of the wind on a particular blade of grass’

Watts always insisted that one had to experience this truth directly, rather than merely consider it in the abstract, in order to derive any serious benefit. But when in the late 1930s and early ’40s he did find himself mulling these ideas, he felt something lacking. As he put it to one of his correspondents:

Yes, we are united with Reality, and cannot get away from it, but unless that Reality is in some profound sense absolutely good and beautiful, what is the use of bothering to think about it?

His love of East Asian art prompted similar questions. He was mesmerised by the ‘turn of a bird’s wing’ and ‘the kiss of the wind on a particular blade of grass’. Talk of artistry or refinement here was beside the point, he thought. The real question was this: how does it come about that human beings possess so nuanced and profound a sense of significance in the natural world?

Watts had tended, up until this point, to picture the Absolute rather hazily as an electric current. This now seemed inadequate to what he felt compelled to imagine and appreciate as a personal dimension to ultimate reality. He was impressed to discover that some of the greatest thinkers in the Christian tradition had always conceived of God in this way: not as a being within the cosmos, but as the source of all, whose nature was ‘personal’ in the sense of being – in Watts’s words – ‘immeasurably alive’.

For anyone who has seen or heard Watts at his best – courtesy, perhaps, of his podcast talks – ‘immeasurably alive’ is quite a good description of the man himself. It is easy to see how a basic understanding of God in these terms might have resonated with him. Watts also had moments when the sheer wonder of life around him made it feel as though it was not merely ‘there’, as brute fact, but was being poured out with extraordinary generosity. It seemed ‘given’, convincing Watts that there must be a giver and filling him with the desire to say ‘thank you’. He found backing for all of this in the writings of the 14th-century German theologian Meister Eckhart and the 6th-century Greek author Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite. It was there, too, in the ‘I-Thou’ thought of the modern Jewish philosopher Martin Buber.

A decade earlier, C S Lewis had completed his journey via Idealism and pantheism to theism. He was far from alone: many in that era, and since, have found the borders between these views – or experiences – of life to be quite porous. In Watts’s case, there may well have been other reasons why he found himself a theist and decided to relocate his family to Evanston in Illinois so that he could train for the Episcopal priesthood at Seabury-Western Theological Seminary. It was, in part perhaps, an attempt to make himself at home in the Christian culture that surrounded him. Some have claimed that his ‘vocation’ was even an attempt to avoid the draft, as the war that he had left Britain to avoid threatened to swallow him up.

The Watts family arrived in Evanston in September 1941, and Watts began an almost decade-long struggle with Christian ideas and practices. Realising that the way people relate to God is shaped profoundly by how they grow up relating to other human beings, Watts found himself questioning his desire to say thank you to some not-less-than-personal dimension of ultimate reality. How straightforward was it, really, to separate out a ‘thank you’ born of wonderment and desire – which might, with luck, lead a person deeper into life’s mysteries – from a ‘thank you’ tinged with feelings of inferiority or a nagging need to please?

The answer became clear the moment that Watts stepped into a church. In Indian traditions, Shiva danced and Krishna played the flute. In the Episcopalian Christianity of his acquaintance, ‘thank you’ was offered up amid heavy wooden furniture that was reminiscent of a medieval monarch’s court or a modern courthouse. There was much talk of ‘grace’ in such places: God’s free, redeeming gift to humanity. But few people brought up in competitive societies like the US found it plausible that something so wonderful was (or indeed ought to be) available free of charge, entirely unconnected to graft or station in life. ‘Corny hymns’ like What a Friend We Have in Jesus suggested to Watts a fake, forced joy, eked out under the gaze of a God who had constantly to be placated through assurances of his gloriousness and implored ‘not to spank [us]’.

Watts’s experience of US Christianity was no doubt rather narrow, but it was far from niche. And what he saw chimed with his broader sense that much of modern Western culture was underpinned by a sense of needing to earn God, salvation or the good life. One detected this, thought Watts, beyond purely Christian language, in the equation of meaning with purpose. The idea that meaning might actually be more closely related to play, and that God might not just be a maker of plans but also – in some meaningfully allegorical sense – a reveller, would strike a great many Americans as blasphemous.

Watts set out to tackle these problems in books like Behold the Spirit (1947) and in his handling of Church services after his ordination and appointment, in 1944, as Episcopal chaplain at Northwestern University. Some of these services were as High Church as he could make them, convinced as he was that the power of the liturgy lay in giving people a sense of the ‘sacred dance’ of the cosmos, eternally moved – as Dante Alighieri pictured it – by love. Other services were casual and intimate, blending conversation, piano improv, jokes, Gregorian chant, smoking and drinking.

Clergy ought not just to teach people but help them unlearn the habits of thought holding them back

Both sorts of service honoured a God who is ‘immeasurably alive’, but over time the second, more bohemian sort began to feel truer for Watts. Desire was a strong feature of his character – as a young man, he had been pleased to find that although ‘the Buddha had taken a dim view of wenching and boozing … he never called it sin’. Still a young-ish man while he was working as chaplain on a college campus, he appears not to have been able to resist the potential for one-to-one counselling sessions with students to become intimate. In the end his first marriage fell apart and he remarried, this time to Dorothy Dewitt, a graduate student in mathematics. In short order, his clerical career concluded and the newlywed couple left Evanston for good.

He had, in any case, struggled to develop a clear idea of how God could be both the Absolute – the ‘ground of being’ as Eckhart put it – and capable of entering into a relationship with human beings. To put it the other way around, how could human beings have their deepest identity in God and be separate enough from God that the idea of a ‘relationship’ could be intelligible?

Here was a difficulty that had bedevilled Western interest in Asian and especially Indian thought for centuries. Samuel Taylor Coleridge had fallen out of love with Indian Idealism when he began to suspect that it was little but a ‘painted Atheism’. For him, the value of nature and solitude lay – in part, at least – in their potential to lead people beyond themselves to the divine source of all. The Idealism of Indian philosophers like Shankara (c8th century) came perilously close, in Coleridge’s understanding at least, to picturing nature as a giant conjuring trick or a veil with nothing behind it. As Coleridge put it in one of his poems:

… If the breath

Be Life itself, and not its task and tent,

If even a soul like Milton’s can know death;

Oh Man! thou vessel purposeless, unmeant …

Coleridge’s qualms about Indian Idealism emerged from an older European squeamishness about pantheism. And this was precisely the heresy of which some of Watts’s colleagues at seminary suspected him.

Watts tried to suggest that a truly all-inclusive God would not be bound by Western logic, with its insistence on mutually exclusive propositions. In Asia, argued Watts, one found not just ‘either-or’ forms of logic but ‘both-and’ forms, too. This was not to say that every Christian must become an accomplished logician. It was a matter, thought Watts, of clergy being trained to do more than ‘go out and bang Bibles in the back woods among lumberjacks and hillbillies’. Like the best of their counterparts in Asia, they ought to be able not just to teach people but to help them unlearn some of the habits of thought and feeling that were holding them back.

In the end, Watts’s personal life helped to render such questions moot. He packed his bags and started life again on the West Coast. For his critics, Watts’s moral failings undermined his idea of a ‘supreme identity’. He had claimed that a person would naturally live a moral life when they had tasted the fruits of that true identity, since so much immorality is the result of insecurity; an ultimately pointless compulsion to look after the interests of a small, mortal self. He had meanwhile objected to traditional moral codes that appeared to expect things to run the other way: do a, b, and c, and there’s a prize for you at the end. Look, his detractors could now say, where a philosophical prospectus that starts from vision rather than morality may take you.

Watts never returned to a serious consideration of Christianity, placing his faith in Zen, Taoism, Hinduism, psychotherapy and good, eye-opening conversation. And yet his period of struggle with Christianity went on to inform the work of countless Christian thinkers after his time, including the Franciscan priest and writer Richard Rohr. It has much to say, too, to our own ‘meaning crisis’. If we imagine the religious instinct as incorporating elements of need, desire and sense of obligation, Watts shows us how necessary – and yet how difficult – it is to hold these three things in balance or tension.

Allow obligation entirely to take the reins, and we risk what Frank Lake, a pioneer of clinical theology, described as a ‘hardening of the oughteries’. For Watts, this revealed itself in people striving to be dutiful or to appear cheerful, or else sitting glumly in the pews when they might be dancing in the aisles. There is a caution, here, for strands of the renewed interest in Christianity that seem focused on battling non-Christian or ‘woke’ forms of thought and ways of living. ‘Cultural Christianity’ of this kind risks locating its beginnings and ends in mere conformity, with little of the joy or vision that one might expect if Christianity is in any meaningful sense ‘true’.

If, on the other hand, need rules us, then we may stay or become Christians out of what Watts described as a collective nostalgia, or a clinging to the past. Again, it is hard not to see something of this in the contemporary mourning of Christianity’s decline by those who regard it primarily as a source of cultural identity – whether of the old church-bells-and-community-feeling sort or a newer and more combative kind, intended for call-up in the culture wars.

Even now, our contemporary conversations about culture and religion often seem ruled by ‘oughts’

What of desire? The pastor and writer Tim Keller, recently deceased, used to say that if religious people don’t desire God, then the chances are that their faith is more about getting something from God – a distinction, he cautioned, which can be hard to discern. Desire may all too easily stop short of its ultimate object, causing people like Watts the sorts of problems to which his critics enjoyed calling attention. A better lesson from Watts’s life might be his honesty about the power of desire in general, and the need to include it – even integrate it – in any search for meaning.

This is where, in retrospect, the inquisitorial style of the New Atheism fell short. By reducing religion to propositions, and testing the faithful on their scriptural knowledge – how can you be a Christian if Richard Dawkins quotes the Bible better than you do? – it made people doubt that emotions, intuitions and desires have any legitimate role in the religious life. Even now, our contemporary conversations about culture and religion often seem ruled by ‘oughts’ – intellectual, moral and political.

From Watts, we learn that desire may be the royal road to truly experiencing reality as gift, of the most recklessly generous kind. For all their differences in temperament, C S Lewis, too, found that desire was the key that unlocked life’s mysteries. His autobiography, Surprised by Joy (1955), is the record of a journey from writing off desire as a feature of biology and psychology to discovering that it is etched into human nature as an invitation from God.

Never having had a mentor on this point, Watts seems to have struggled with the art of discernment. And as the disappointed editor of his autobiography, In My Own Way (1972), could have told you, he didn’t enjoy digging very deep into his own emotions and motivations. The ‘supreme identity’ was handy in this respect, since the small, everyday self could be dismissed as unworthy of much attention.

But when has recognising, exploring and ordering our desires ever been easy? In his writings, and in the contours of his eventful life, Watts has bequeathed us a passionate and persuasive advocate for the exploratory potential of desire. Either everything is religious, or nothing is: this was his message, and it may be the only basis on which people will consider religion worth bothering with beyond the 2020s. For those who try to live this way, holding that balance of need, desire and a sense of ‘ought’ – responsibility to others and to the divine – it may be no bad thing to have the spirit of Alan Watts hovering somewhere overhead.

Correction, 5 March 2024: This essay originally stated that Alan Watts’s affair with Dorothy DeWitt caused the end of his first marriage with Eleanor Everett.