For six decades, Bob Dylan has challenged listeners with songs that reward interpretation. Critics and fans have long pored over his words, treating them as literary texts worthy of a slow, devotional reading, line by line, image by image. In 2016, Dylan even won the Nobel Prize in Literature. As the Swedish Academy put it, the prize honoured him for ‘having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition’. But what more might we discover if, instead of a human scholar, we asked an artificial intelligence to sift through every word Dylan ever wrote? What patterns, connections or evolution in Dylan’s massive body of lyrics might reveal themselves to a machine’s analysis, and what could that tell us about the man and his music?

These questions aren’t as far-fetched as they once sounded. Today’s AI systems, especially large language models (LLMs) capable of ‘reading’ and analysing text at scale, offer new ways to study art and literature. Think of it as a form of ‘distant reading’, the approach championed by the literary scholar Franco Moretti, which uses algorithms to examine large collections of texts from a bird’s-eye view. A computer can crunch through hundreds of songs and identify patterns or themes that no individual reader could easily quantify. The advantage over classic criticism is vast coverage, consistent measurement, and the power to trace changes across time.

Dylan’s lyrics invite us to return again and again, each listen revealing a new meaning or shade. The biopic A Complete Unknown (2024) renewed public interest, but my reasons for a deep dive were already both personal and technical. My research uses AI to trace cultural messages across networks, and I wanted to test whether the same tools could illuminate Dylan’s work as well. Could machine analysis measure the qualities that make Dylan’s songs resonate – how complexity arises, how new images mix with the familiar, how ambiguity threads through songs?

So I fed Dylan’s official discography from 1962 to 2012 into a large language model (LLM), building a network of the concepts and connections in his songs. The model combed through each lyric, extracting pairs of related ideas or images. For example, it might detect a relationship between ‘wind’ and ‘answer’ in ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’ (1962), or between ‘joker’ and ‘thief’ in ‘All Along the Watchtower’ (1967). By assembling these relationships, we can construct a network of how Dylan’s key words and motifs braid together across his songs.

To build that network, I passed every Dylan song through an LLM, one song at a time. The model treated each notable concept it encountered (such as ‘wind’, ‘answer’, ‘joker’, ‘thief’ and so on) as a node (the individual entities or concepts that surface in the songs). Two nodes were connected by an edge, representing the relationship between them. For instance, the LLM drew an edge between wind and answer in the line ‘The answer is blowin’ in the wind.’ Each edge was then categorised as literal or metaphorical, and its emotional tone tagged as positive, negative or neutral.

Because the model processes every line uniformly, it lets us measure (not just claim) how often, where and with what emotional charge any two ideas co‑occur, something no human analysis or close read has ever done at scale. After more than 500 songs, the process yielded roughly 6,000 unique nodes connected by about 9,000 edges. The resulting bird’s-eye map shows, for example, how a metaphor in ‘A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall’ (1963) resonates with a later allusion in ‘Not Dark Yet’ (1997), or how a single biblical name reappears, but may be connected to a different concept and in a different mood.

Network‑science tools similar to those used in epidemiology or social‑media analysis are increasingly common in humanities labs, yet Dylan offers a rare test case of a single author whose output is vast, poetic and varied. Free of the limits of any one reader’s memory, the technique provides an objective framework to trace shifts in tone, thematic recurrence and metaphorical density across the entire body of songs. Our goal is not to replace the act of close reading, but to offer a fresh vantage point, so that we can see each lyric both in its own right and as part of a richly connected tapestry we might otherwise overlook.

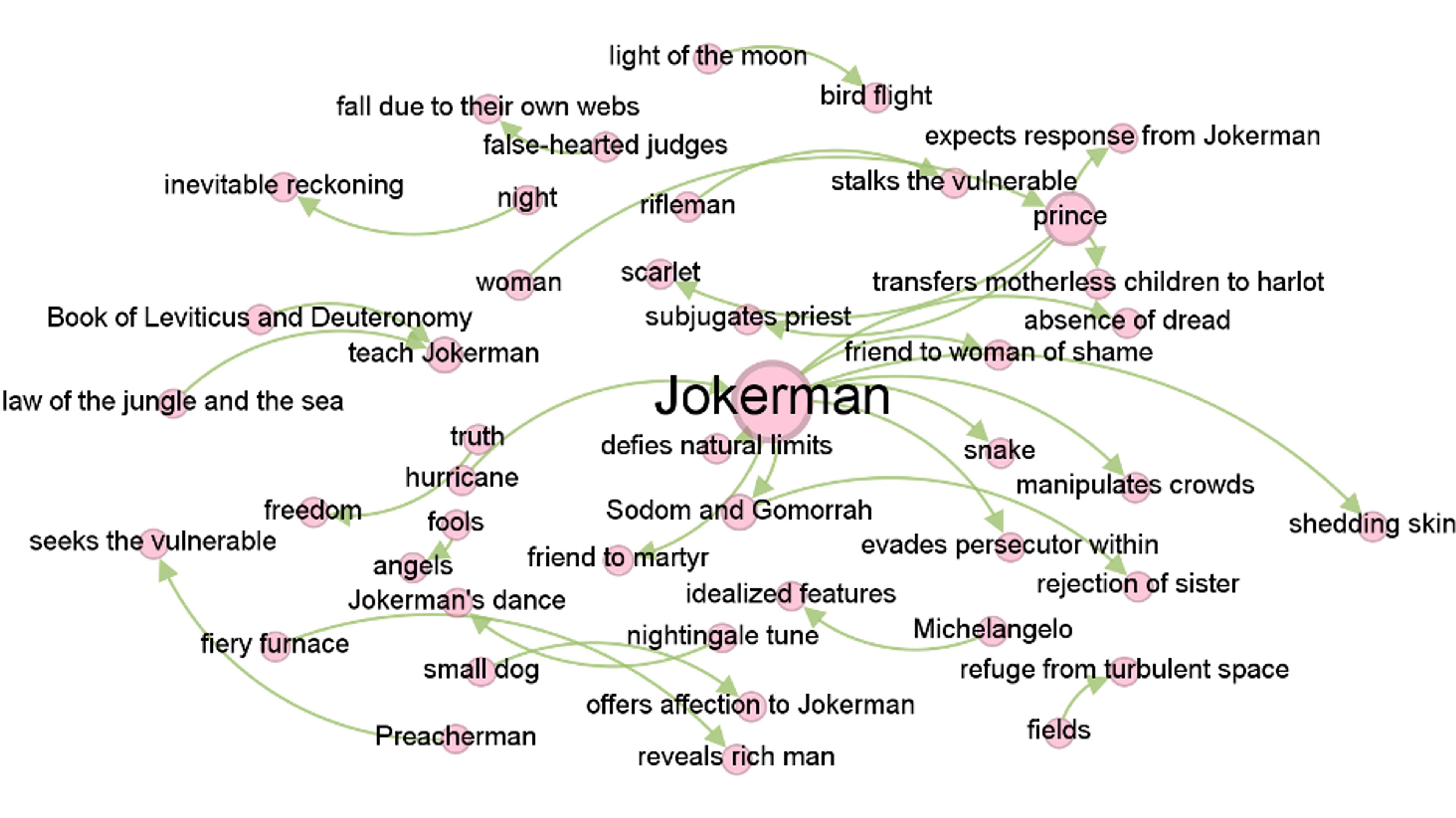

To make this abstract idea more concrete, consider Dylan’s ‘Jokerman’ (1983), one of his most celebrated 1980s tracks. Figure 1 below is a network diagram for the song. Each node appears as a pink circle whose size reflects how often that concept shows up in the lyric, while arrows mark edges, indicating connections between ideas. At the centre, the Jokerman himself connects to a vivid set of nodes: the prince, the preacherman, Sodom and Gomorrah, and Michelangelo.

Figure 1. Example network diagram: nodes represent entities or abstract concepts; node size = frequency; edges (arrows) represent connections between nodes

The diagram hints at the song’s dazzling variety: ‘Jokerman’ reaches into images of a biblical ‘fiery furnace’, a loyal little dog, the Book of Leviticus, a lurking rifleman and preacherman, and countless other details. These findings validate the linkages that longtime Dylan fans have observed. Critics have often noted Dylan’s knack for blending the biblical with the everyday, casually dropping an Old Testament reference into a song that also mentions modern riot gear and tropical birds.

Across six decades, Dylan’s writing grows more figurative, his metaphors crowding out the plainspoken

Stepping back from this song-by-song snapshot, we built the same network for every track in Dylan’s catalogue, and then merged all the nodes and edges, decade by decade. Each edge – like the one linking ‘Jokerman’ to Michelangelo – marks a moment when one lyrical idea points to another. We asked the LLM to label each connection as literal (eg, ‘the pump don’t work ’cause the vandals took the handles’) or metaphorical (eg, ‘a hard rain’s a-gonna fall’).

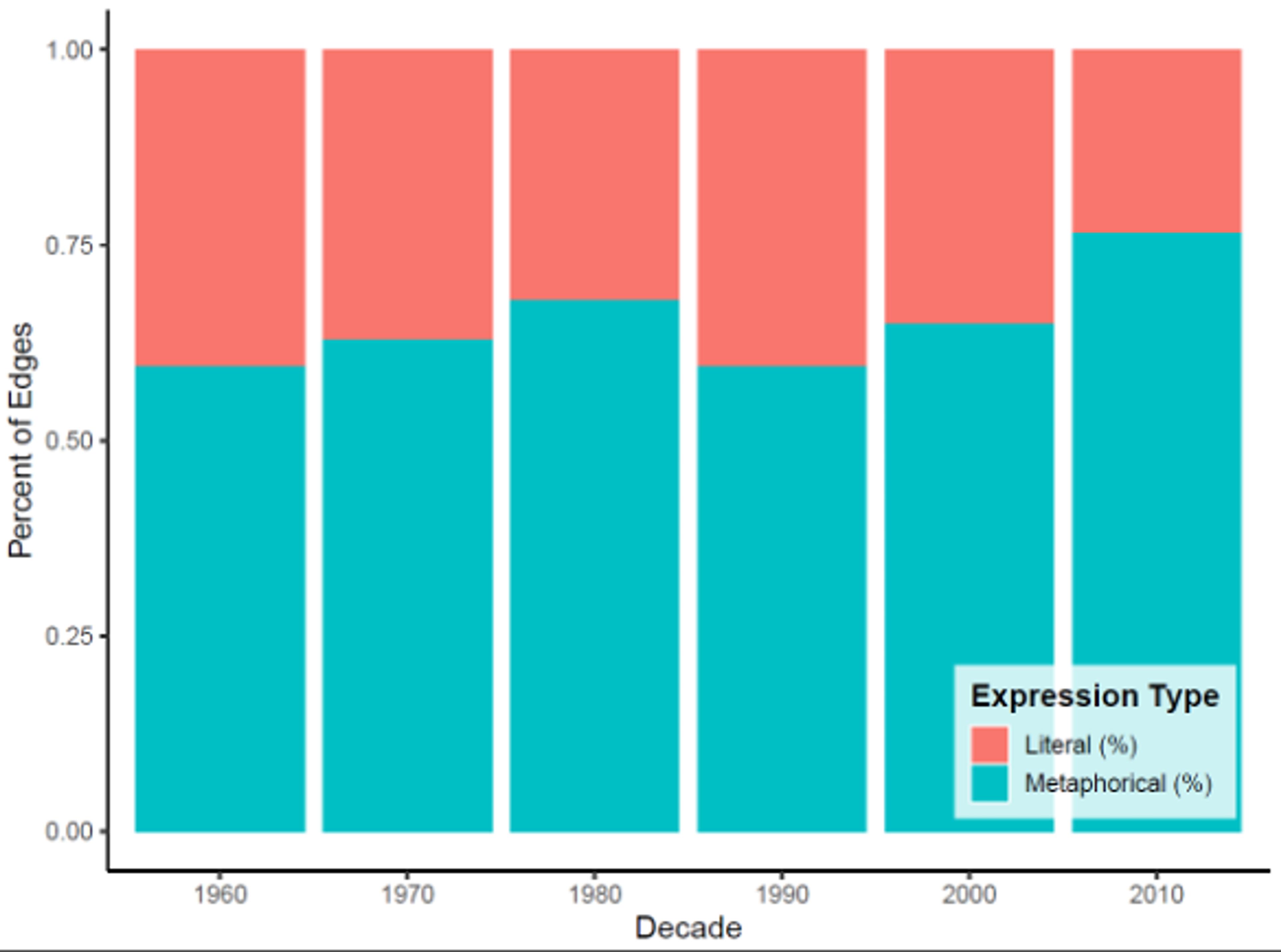

Figure 2 below makes the changes across time unmistakable: Dylan’s lyrics move from a near balance of literal and metaphorical expression in the 1960s, to a catalogue where metaphor steadily takes the lead. In the 1960s, about 60 per cent of edges are metaphorical and 40 per cent literal. By the 1980s, metaphor pushes past two-thirds. By the 2010s, it swells beyond 75 per cent, leaving literal connections at less than a quarter. The trend is clear: across six decades, Dylan’s writing grows more figurative, his metaphors crowding out the plainspoken. Critics had long sensed that Dylan grew more oblique, but the AI lets us put a number on it: metaphor’s share climbs 1–2 percentage points per album, a change too gradual for the naked eye to track.

Figure 2. Percentage of edges (connections between entities in Dylan’s lyrics) that are metaphorical rises steadily; literal statements fall across six decades

Why does this matter? Metaphor is often where an artist’s emotional truth comes out. Interestingly, I find that Dylan’s metaphorical expressions tend to carry a more negative emotional tone on average than his literal statements. For example, when Dylan sings ‘the emptiness is endless, cold as the clay’, from ‘Mississippi’ (2001), or ‘evening’s empire has returned into sand’, from ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ (1965), the LLM tags these as metaphorical edges, and finds that they convey melancholia or loss. By contrast, more literal lines like ‘may God bless and keep you always’, a line from ‘Forever Young’ (1974), tend to be more positive or neutral, according to the model.

Dylan’s overall emotional expression shifts as his life and art unfold. His early 1960s protest songs often mix anger at injustice with an undercurrent of hope; take ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, which highlights pain (‘how many times must the cannonballs fly’) but also insists the answer is still blowing in the wind. By the mid to late 1960s, Dylan’s lyrics in songs like ‘All Along the Watchtower’ or ‘Desolation Row’ (1965) had grown more surreal and cynical, reflecting the tumults of the era with imagery of jokers and thieves and a world gone wrong. In the 1970s, after a retreat from political anthems, Dylan wrote more about personal relationships. The album Blood on the Tracks (1975) is bittersweet, soul-baring, and infused with metaphors of weather and water to describe heartbreak. Then came the born-again period around 1979-81, which takes on an urgent, sermon-like literalness about salvation and sin (though even these are couched in biblical metaphor). By the 1990s, Dylan’s work turned darker and introspective, with mournful masterpieces like ‘Not Dark Yet’. The late 1990s see an uptick in concepts related to mortality and a prevalence of negative-sentiment words (dark, cold, end, etc), corresponding to Dylan’s age and the reflective, sometimes bleak outlook of albums like Time Out of Mind (1997). And yet, true to Dylan’s volatile nature, the 2000s also feature playful romps (he won an Oscar for the wry ‘Things Have Changed’ in 2000) and historical sagas (the 14-minute ‘Tempest’ in 2012 recounts the Titanic sinking in vivid detail).

Commentators often divide Dylan’s career into distinct eras: the young folk troubadour of the early 1960s, the electric rock poet of the mid-1960s, the country crooner of the late 1960s, the introspective songwriter of the 1970s, the passionate gospel preacher around 1980, and the reflective sage from the 1990s onward.

Unlike the neat eras described by traditional criticism, the AI graphs below are driven by data: they emerge from 9,000 connections between concepts, not from my preconceptions. By tracking thematic patterns across these phases with the help of an LLM, we uncover how Dylan’s changing concerns align with his age, experiences, and the broader cultural currents of his times.

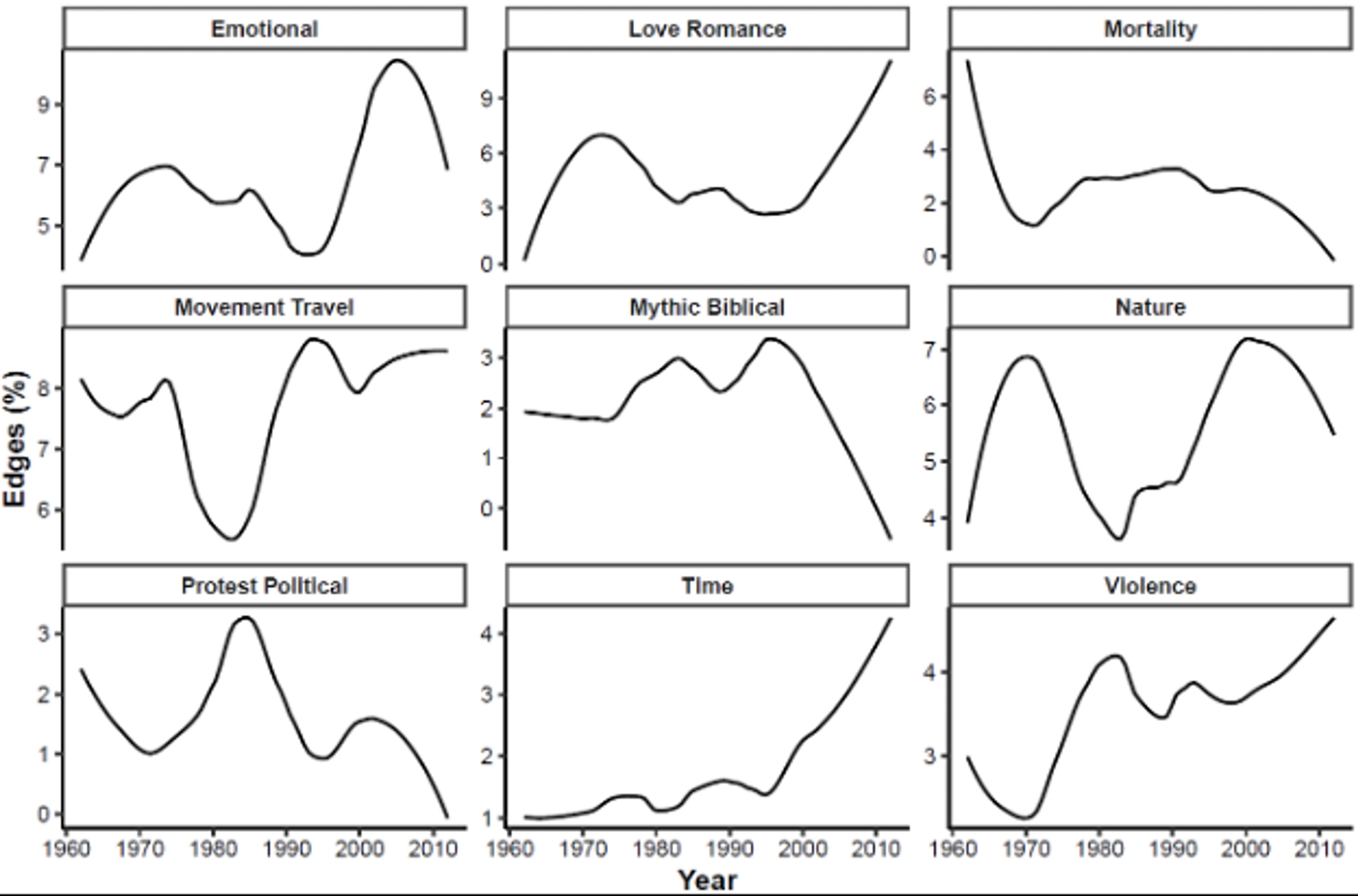

The protest/political theme surges dramatically in the 1960s

Ultimately, the model turns sentiment into timelines with peaks and troughs. The emotion in Dylan’s music has always been dynamic, not static, and the LLM’s sentiment analysis reflects that, showing rises and falls in average song sentiment that align with major chapters of Dylan’s life and six-decade career (see Figure 3 below).

Figure 3. Evolution of themes in Dylan’s lyrics across the years

In the mid-1960s, journalists were hailing Dylan as the voice of a generation. That reputation is borne out in the data: the protest/political theme surges dramatically in that decade, driven by iconic songs such as ‘Masters of War’ (1963) and ‘The Times They Are A-Changin’’ (1963). The theme of violence, unsurprisingly, tracks alongside the era’s unrest. By the decade’s end, however, Dylan’s pivot to electric rock and his step back from overt commentary coincide with a sharp drop in protest imagery. In its place, themes of love/romance and emotion rise to the fore, mirroring both Dylan’s turn inward and a broader cultural shift from mass movements to personal reflection.

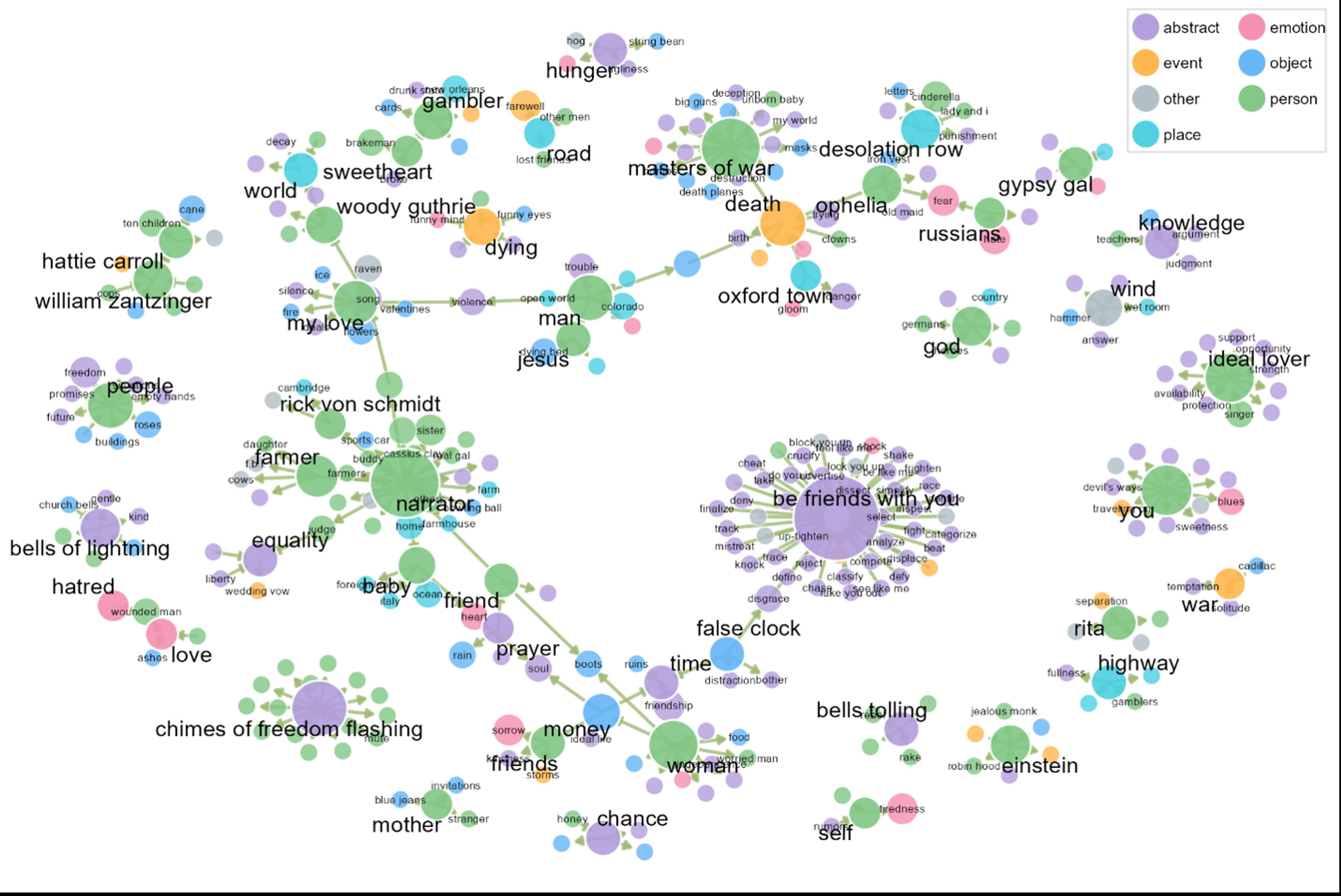

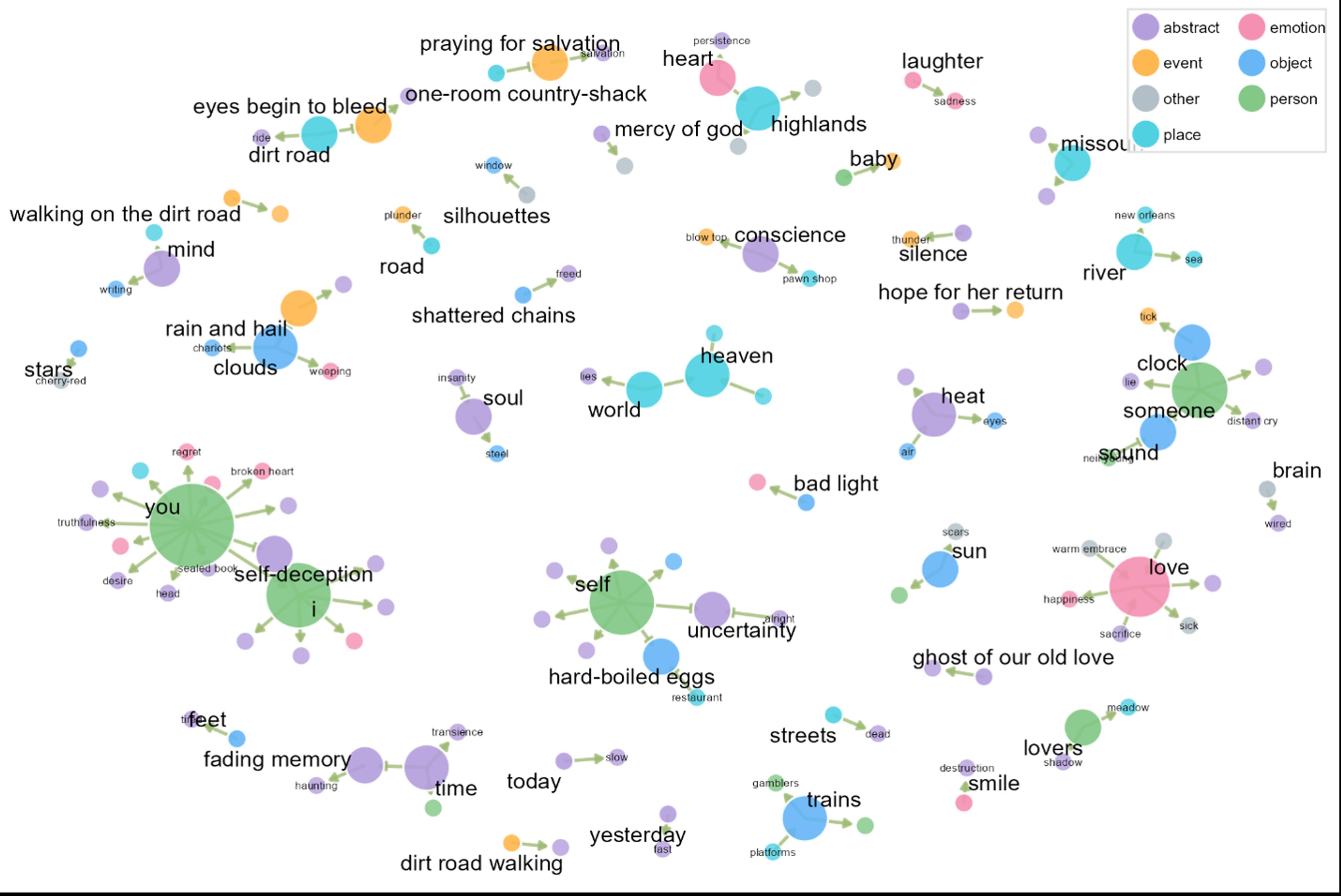

It helps enormously to see Dylan’s body of work, and the networks they generate, decade by decade. The diagrams below show the 50 most prevalent nodes for each decade along with the edges between them. As you look through the diagrams, remember that node size reflects connectivity, and colours mark broad node types, from abstraction to individual people. The point is to compare changes over time. The 1960s network (see Figure 4 below) shows protest and reportage as the main hubs, with a surreal collage threaded through a few bridge concepts.

Figure 4. Top 50 concepts network, 1960s: the model shows two dominant clusters: a protest cluster (‘masters of war’, ‘Oxford town’, named figures such as Hattie Carroll and William Zantzinger) and a surreal‑literary cluster (‘desolation row’, Ophelia). A small set of bridges connect these worlds, such as ‘death’, ‘highway’, and the wind → answer hinge. This makes visible how reportage and myth are wired together in the early work rather than living in separate registers

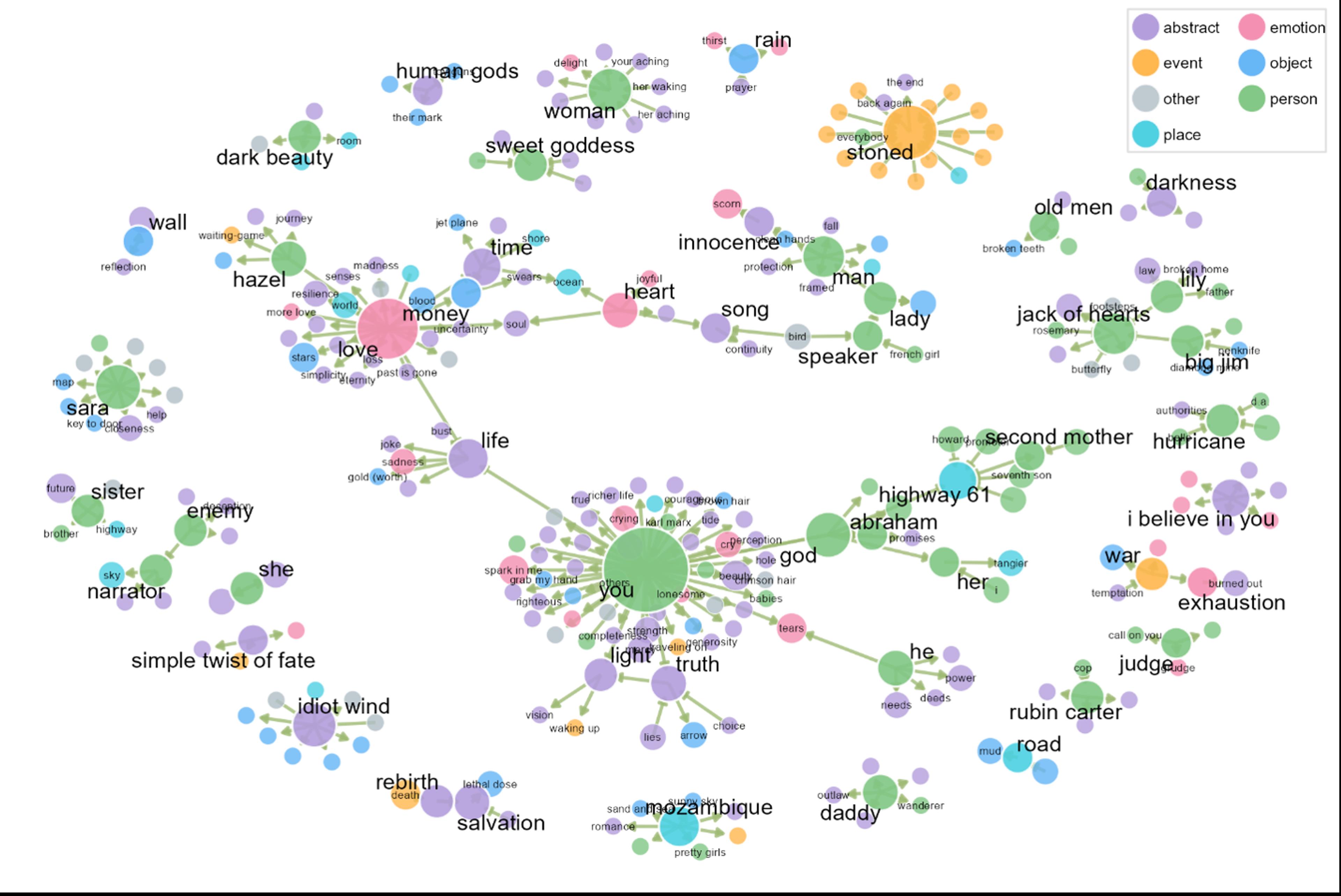

Meanwhile, the 1970s, as diagrammed in Figure 5 below, see Dylan fully immersed in personal themes. The decline of explicitly political and violent imagery continues, coinciding with Dylan’s retreat from the public eye into family life and personal reflection (he married Sara Lownds in 1965 and settled in Woodstock). Romantic, emotional themes peak during the mid-1970s, especially notable on the album Blood on the Tracks (1975), widely interpreted as being inspired by Dylan’s marital strife, producing intimate classics such as ‘Tangled Up in Blue’ and ‘Shelter from the Storm’. Nature imagery also rises, reflecting Dylan’s introspective turn and his increasing use of pastoral and environmental metaphors.

The centre shifted in the 1970s to second‑person address and intimate themes

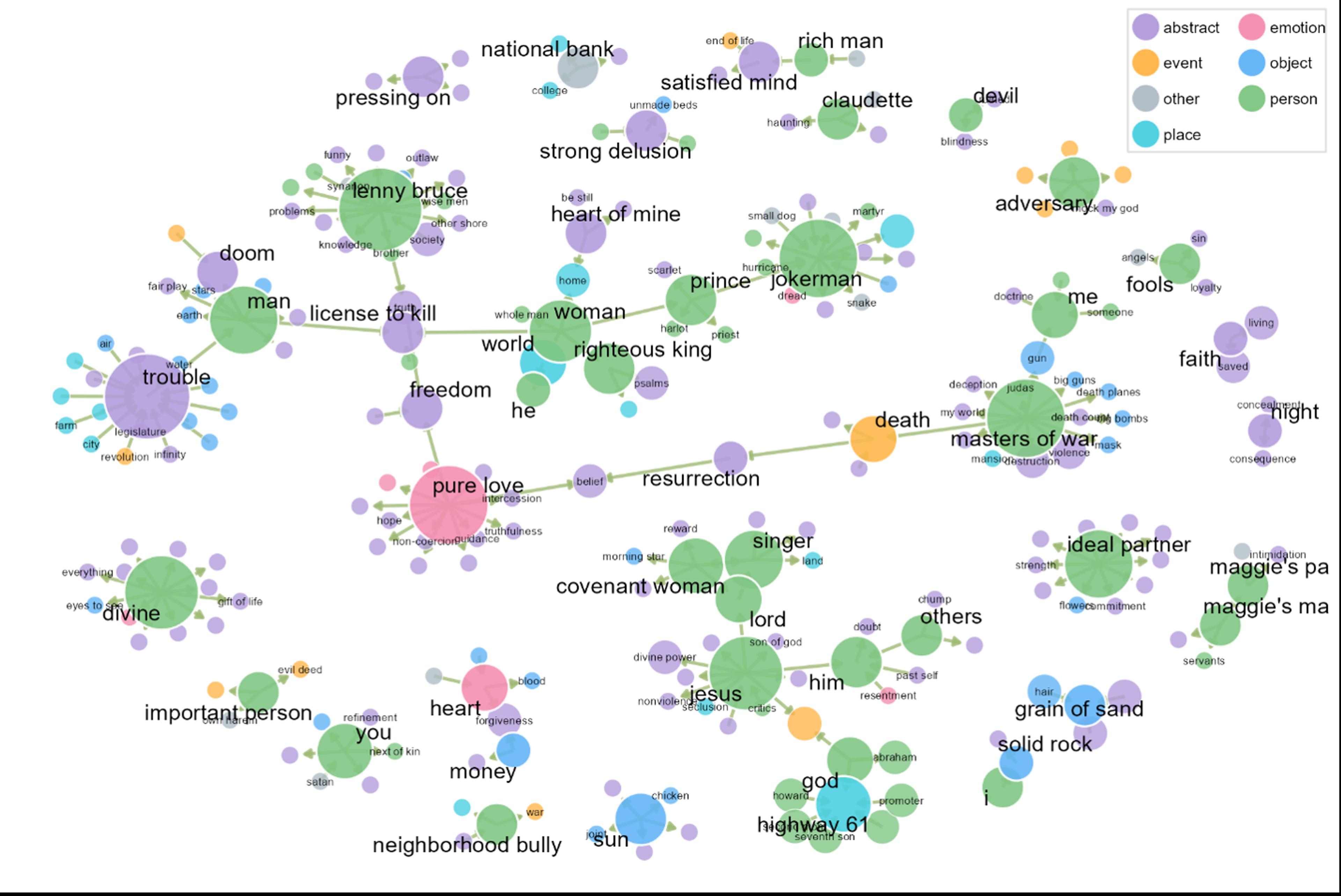

In the late 1970s to early ’80s, Dylan experiences a dramatic thematic reversal. Themes of protest and violence return prominently around 1980, aligned with political critiques such as ‘Union Sundown’ (1983) and ‘Neighborhood Bully’ (1983). Simultaneously, mythic/biblical imagery sharply increases as Dylan undergoes his highly publicised evangelical Christian phase, marked by albums like Slow Train Coming (1979) and Saved (1980). During this period, movement and travel themes reach their lowest point, perhaps reflecting Dylan’s inward, spiritual journey rather than outward wandering.

The shift from love and emotional introspection toward broader social and spiritual concerns defines this tumultuous period. Indeed, the centre shifted in the 1970s to second‑person address and intimate themes (see Figure 5 below). In the 1980s, explicitly religious vocabulary becomes central and linked directly to geopolitical language (see Figure 6 below).

Figure 5. Top 50 concepts network, 1970s: the centre of gravity shifts to second‑person address and private life. A single hub around ‘you’ pulls in love, life, truth, light, money, and named figures such as Sara; distinct story clusters (‘Hurricane’, ‘Idiot Wind’, ‘Jack of Hearts’) hang off that hub. The topology quantifies the decade’s turn inward: more edges converge on address and relationship terms than on public themes, a change that is easy to miss without a macroscope

Figure 6. Top 50 concepts network, 1980s: religious vocabulary becomes structurally central (Jesus, lord, covenant woman, resurrection, righteous king) and links directly to worldly nodes like licence to kill and neighbourhood bully, and to the metaphor‑rich ‘Jokerman’ cluster. The network shows not two vocabularies but one mesh. It also reveals that religious terms act as bridges rather than islands, connecting moral language to political critique with high betweenness

The 1990s see another thematic shift, this time marked by Dylan’s return to the role of the wandering observer. Protest themes recede once more, while travel and nature imagery rebound. This revival is illustrated in songs like ‘Tryin’ to Get to Heaven’ (1997) and ‘Highlands’ (1997) where movement, journeys and natural imagery are central. Romantic imagery remains subdued, continuing to decline from the emotional intensity of the 1970s. Songs about love reach their lowest ebb as Dylan’s narratives increasingly take on a more detached, reflective stance, perhaps mirroring his personal stage of life and cultural introspection at the millennium’s end.

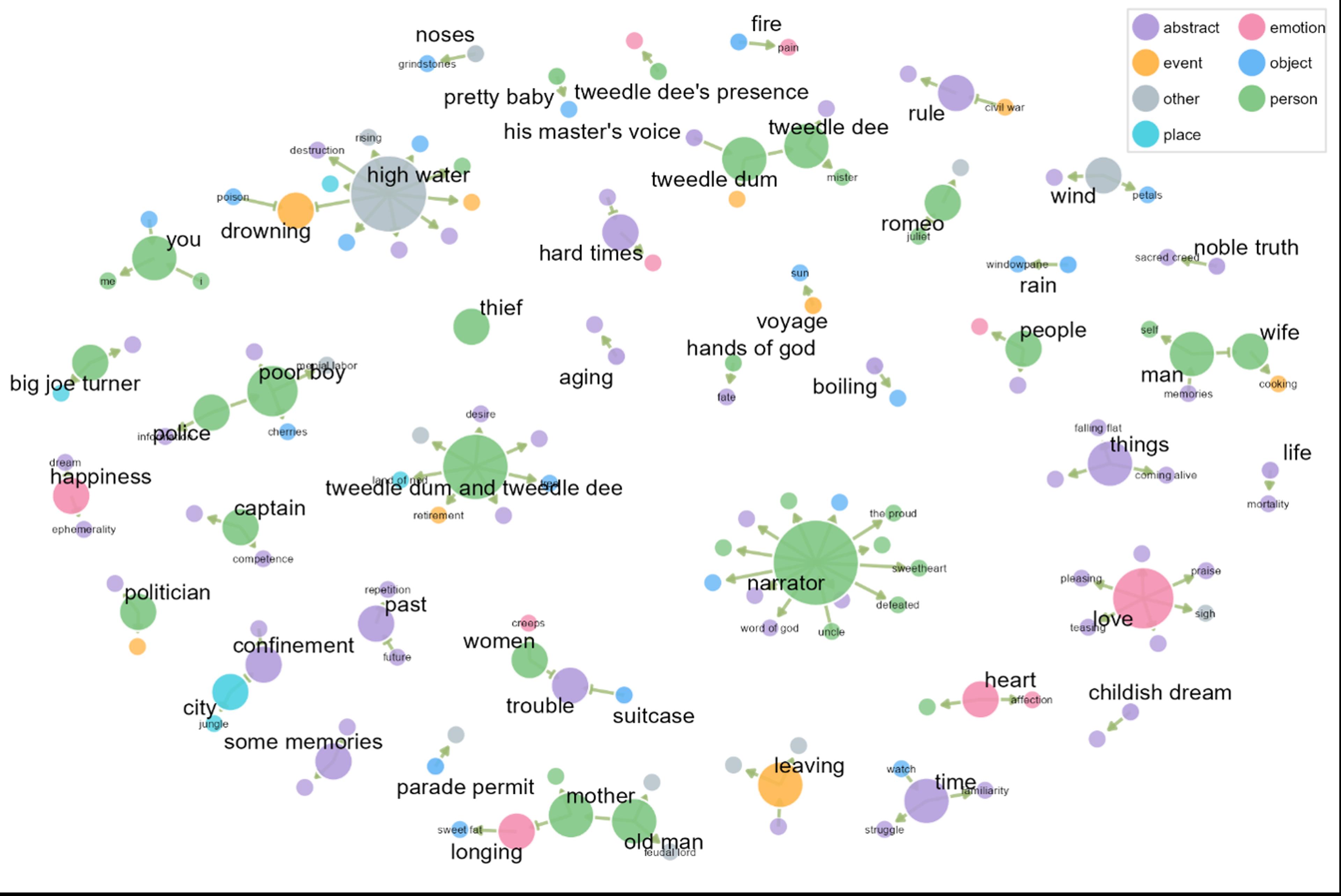

By the 1990s, the network fragments into smaller clusters tied to memory and self‑scrutiny

Finally, from the 2000s up to 2012, Dylan enters a phase defined by reflection and emotional complexity. Love and romance imagery notably rise to the highest levels, indicative of a late-career openness to personal reflection and emotional candour, evident in albums like Modern Times (2006) and Together Through Life (2009). At the same time, mythic imagery along with themes like protest and violence fade, suggesting reduced engagement with external controversies or spiritual fervour. Movement and travel remain persistently high: Dylan never stopped moving, both figuratively and literally (he’s famously toured relentlessly since the 1980s on his Never Ending Tour).

Notably, by the 1990s, the network fragments into smaller clusters tied to memory and self‑scrutiny (see Figure 7 below). In the 2000s, the centre loosens again into modular Americana, with fables and historical images informing the narrator’s voice (see Figure 8 below).

Figure 7. Top 50 concepts network, 1990s: the network fragments into smaller modules tied to inward themes: self‑deception, uncertainty, ghost of our old love, temporal markers today/yesterday, and long‑walk images from ‘Highlands’. The loss of a single address hub and the rise of time and memory nodes quantify the decade’s introspective turn and help explain why the sentiment of metaphor edges skews darker here

Figure 8. Top 50 concepts network, 2000-12: the structure settles into modular Americana. Clusters such as Tweedle Dum and Tweedle Dee, high water, and a general narrator hub sit beside archetypes (thief, captain, poor boy) and philosophical tags (noble truth). The network shows a return to collage, but with looser centrality than the 1970s address hub, and tighter motifs than the 1960s sprawl, which is easy to miss without a consistent decade‑wide measure

One theme steadily rises over the entire course: time. Its persistent ascent through the decades aligns intuitively with Dylan’s own ageing and increasing preoccupation with legacy, and the passage of years.

What’s striking is how Dylan’s thematic tides mirror both his life stages and wider cultural shifts: the Cold War and civil rights turmoil of the early 1960s, the inward turn to domestic and romantic subjects in the mid-1970s, the spike in evangelical imagery around 1980, and the reflective, legacy-minded tone of the 1990s.

Underlying all these patterns is that enduring quality of Dylan’s art: reinvention. He never stays the same. The line ‘a complete unknown’ – taken from the song ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ (1965), and the title of the 2024 biopic – is a fitting epithet for an unpredictable artist like him. In mid-1965, the up-and-coming folk artist who defined protest music at Newport Folk Festival stunned folk purists by going on stage with an electric band. A few years later, just when many expected another rock record, he surprised fans again with Nashville Skyline (1969), a gentle country album. In the late 1970s, he turned from secular poet to born-again Christian, only to veer back toward rock, blues and flirtations with hip-hop in the late 1980s. Each transition drew howls from some fans and critics, yet Dylan always moved on.

In his essay ‘On Bob Dylan’ (2022), the legal scholar Cass Sunstein describes this restless shape-shifting as ‘dishabituation’: the deliberate disruption of expectations that keeps an audience awake and alive to what comes next. Since unpredictable stimuli trigger dopamine release, this neurochemical payoff may explain why Dylan’s wildest phases remain so addictive.

Sunstein points to Dylan’s expressions of delight in the off-kilter, or as Dylan himself puts it, his ‘songs about roses growing out of people’s brains and lovers who are really geese and swans that turn into angels.’ Dylan, Sunstein notes, mocks ‘rote or routine’, and refuses to clap dutifully at protest slogans. That irreverence, Sunstein argues, explains everything from Dylan’s refusal to become a 1960s movement mascot to the rootless exhilaration of ‘Like a Rolling Stone’.

The data support this interpretation. Think of the network of nodes as a subway map of Dylan’s mind: with Grand Central stations named Love, Time, God at the centre; and branch-line stops called Nightingale or Fiery Furnace on the fringe. In network theory, the bustle around each station (a node) is called its centrality: the more connections a node has to other nodes, the more ‘central’ it is.

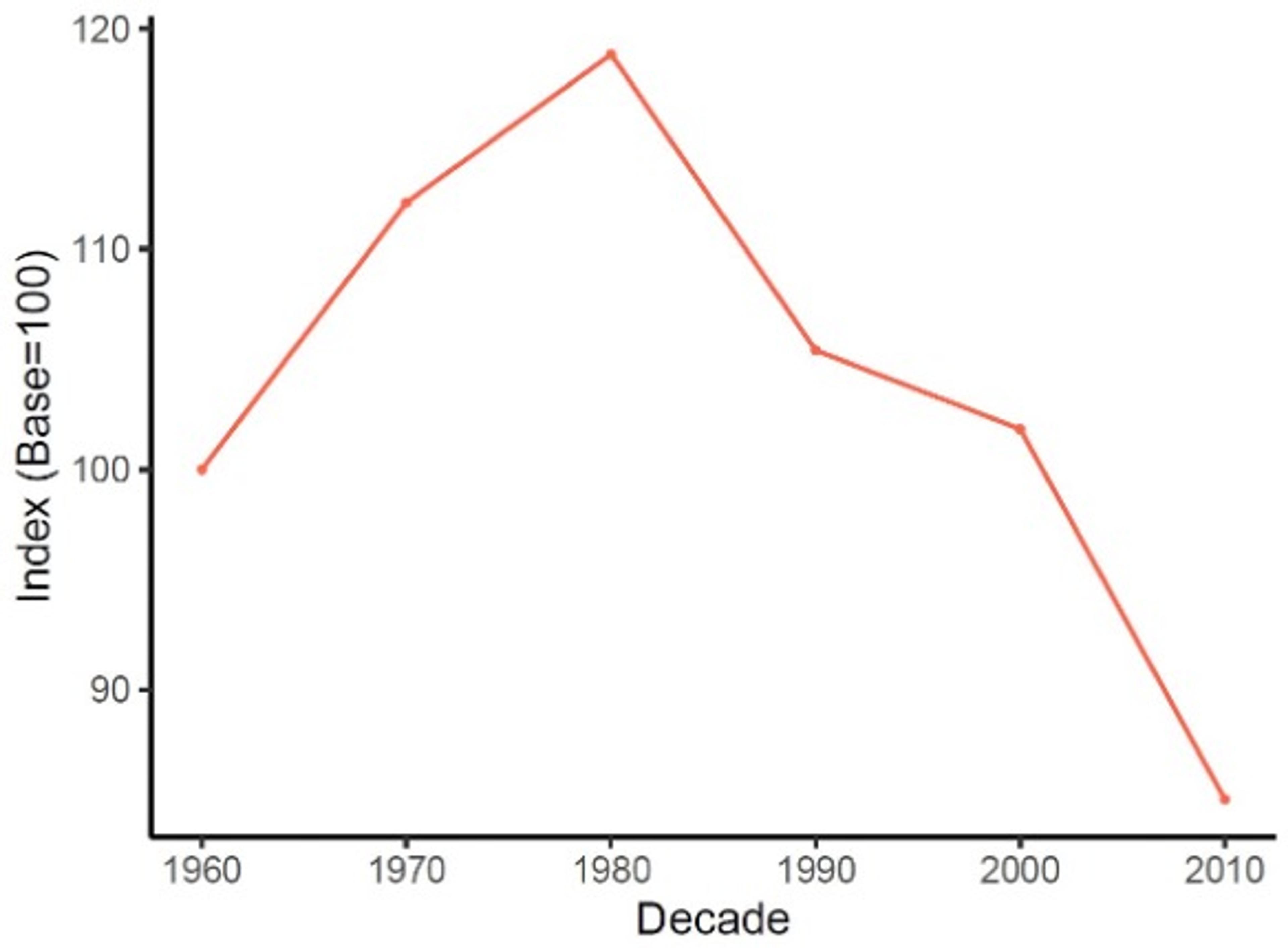

Variance spikes in the 1980s, when Dylan was darting from gospel rock to folk revival to synth-tinged pop

Now imagine measuring how much a song wanders between its central ideas. If the imagery circles only a few familiar hubs, the variance is low. If it leaps unexpectedly between the common and the rare, the variance is high. That spread serves as a rough ‘dishabituation index’: high variance means Dylan jolts us with a mash-up of the familiar and the unexpected, while low variance means he’s moving through well-worn territory. Similar measures of variation have even been used to capture the element of surprise in jazz solos, suggesting a bridge between Dylan’s lyrical experiments and musical improvisation.

Plotted decade by decade (see Figure 9 below), the index for variance spikes in the 1980s, precisely when Dylan was darting from gospel rock to folk revival to synth-tinged pop. After that, it drifts downward, pointing to the more unified voice that emerges on albums like Time Out of Mind (1997) and beyond. After 1997 it settles – not tame, but tempered – the improviser growing into his groove.

Figure 9. Dishabituation index over the years: the higher the index, the more Dylan is mixing core nodes (ones with high centrality) with peripheral ones

Quantifying unpredictability may sound paradoxical, but the result offers the first hard-number confirmation of something fans have long intuited: Dylan’s appetite for surprise reached its wildest heights in the 1980s, then gradually settled into a seasoned but still restless maturity. Musicologists have long called the 1980s Dylan’s most wayward decade; the dishabituation index is the first numeric proof.

Sceptics might ask: do we really need an AI to tell us that Dylan wrote protest songs in the 1960s, gospel songs in the 1980s, and introspective laments in the 1990s? At one level, no. But as the historians Jo Guldi and David Armitage argue in The History Manifesto (2017), quantitative evidence and visualisation let historians test received wisdom and engage public debate with arguments that circulate beyond the academy, helping to arbitrate between falsity, myth, and noise.

The value lies in the detail and the confirmation. The model can pinpoint exactly which biblical names surge in the gospel period, how often ‘rain’ recurs across six decades, or how train imagery rises again in Dylan’s 21st-century records. It shows, for instance, that lines tagged love/romance grow more ambivalent in their emotional tone with age, quantifying a shift from youthful idealism to mature complexity. These empirical signposts don’t replace human interpretation; they spark new questions. Why did Dylan’s metaphors multiply so sharply? Was it artistic strategy, the influence of age, or simply the culture of the MTV era pushing lyrics toward abstraction?

Dylan’s personal turns often mirror broader cultural currents: his protest songs echo the civil rights era; the gospel phase aligns with a nationwide religious revival; his late-career meditations reflect a generation grappling with legacy. This observation, which we usually understand anecdotally, becomes clearer as we visualise lyrical trends over decades. Digital humanities scholars like Ted Underwood caution that data never replace close reading, but can offer a ‘macroscope’, re-framing familiar works in surprising, illuminating ways.

Of course, no algorithm can tell us why ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ still gives us chills, or decode the moral ambiguity of ‘to live outside the law you must be honest.’ More critically, sceptics remind us that large language models can behave as mere ‘stochastic parrots’, echoing surface patterns without real understanding. Yet, when used as a lens rather than an oracle, the same models can jolt even seasoned critics out of interpretive ruts and reveal themes they might have missed. Far from reducing Dylan to numbers, this approach highlights how intentionally intricate his songwriting is: a restless mind returning to certain images again and again, recombining them in ever-new mosaics. In short, AI lets us test the folklore around Dylan, separating the theories that data confirm from those they quietly refute.

Would Dylan himself approve? Probably with a wry grin. His career teaches, above all, the value of new perspectives. Each reinvention forces listeners to drop their assumptions and hear with fresh ears. Few bodies of work reward that double vision more than his. Machine analysis cannot touch the emotional resonance of the songs, but it can trace their shifting architecture – reminding us that, despite the revelations, Dylan’s cultural power lies in remaining, even now, a complete unknown.