Suppose you want to be a better person. (Lots of us do.) How might you go about it? You might try to become more generous and commit to donating more of your income to charity. Or you might try to become more patient, and practise listening to your partner, instead of snapping at them. These commonsense prescriptions invoke an ancient ethical tradition. Generosity and patience are virtues – excellences of character, whose exercise makes us flourish. To live well, says the virtue ethicist, is to cultivate and exercise just such excellences of character.

Part of living well, though, is thinking well. Our souls have an intellectual, as well as a practical, part; we cannot live fully flourishing lives unless we flourish intellectually. Are there, then, specifically intellectual virtues – excellences of intellectual character, whose exercise makes us good thinkers? Aristotle – whose works remain a touchstone for contemporary virtue theorists – certainly thought so. The intellectual part of the soul, he wrote in his Nicomachean Ethics, strives to attain truth; accordingly, he thought, the intellectual virtues are just those dispositions that qualify it to perform this function. Where the virtue ethicist bids us to be generous and patient, temperate and brave, the virtue epistemologist bids us to be thoughtful and fair, to be diligent and open-minded. At their most ambitious, the virtue epistemologist argues not just that such traits are valuable for their own sake, or that the exercise of such virtues will (tend to) yield knowledge, but, further, that our grasp of what knowledge is, in the first place, parasitic on our understanding of such virtues. If I know that – say – DNA has a double helix shape, that’s because I believe what an intellectually virtuous agent would believe about DNA, under circumstances similar to mine.

Barbara McClintock’s unpublished index of maize specimens, 1971. Courtesy the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Like everything else, virtues go in and out of style. One purported intellectual virtue in particular has recently become intensely fashionable. Philosophers, psychologists and journalists all urge us to be more intellectually humble. Different thinkers characterise intellectual humility differently, but there are some recurring themes. The intellectually humble have a keen sense of their own fallibility (‘I’ve been mistaken in the past’). They tolerate uncertainty (‘We might never know the full truth of what happened’). They recognise the partiality and ambiguity of their evidence, along with the limits of their ability to assess it (‘New information might come to light’; or ‘I might be misinterpreting this data’).

Intellectual humility was rarely discussed between 1800 and the early 2000s, but in the early 2010s, the number of mentions the trait received began to grow exponentially. Enthusiasm for intellectual humility, then, looks to be bound up with a specific set of epistemological anxieties related to information management in the age of the internet and social media. (Facebook was founded in 2004.) And, indeed, intellectual humility is often said to guard against precisely those pathologies that social media can incubate. ‘When citizens are intellectually humble,’ write the philosophers Michael Hannon and Ian James Kidd, ‘they are less polarised, more tolerant and respectful of others, and display greater empathy for political opponents.’ The intellectually humble, writes the psychologist Mark Leary, ‘think more deeply about information that contradicts their views’, and ‘scrutinise the validity of the information they encounter’.

But the empirical work that underwrites these glowing assessments is often questionable. Many studies assess the intellectual humility of their experiments’ participants via self-reports. Subjects are asked to rate their level of agreement with claims like ‘I am willing to admit it if I don’t know something’; those who rate high levels of agreement are classed as having a high level of intellectual humility. The worry is not just that we are often poor judges of our own strengths and weaknesses, but rather, more specifically, that it is precisely those who are lacking in humility who are likely to give themselves high scores. Humble people, after all, don’t go around talking about how humble they are. To say ‘I’m very humble’ makes for a comically self-undermining boast.

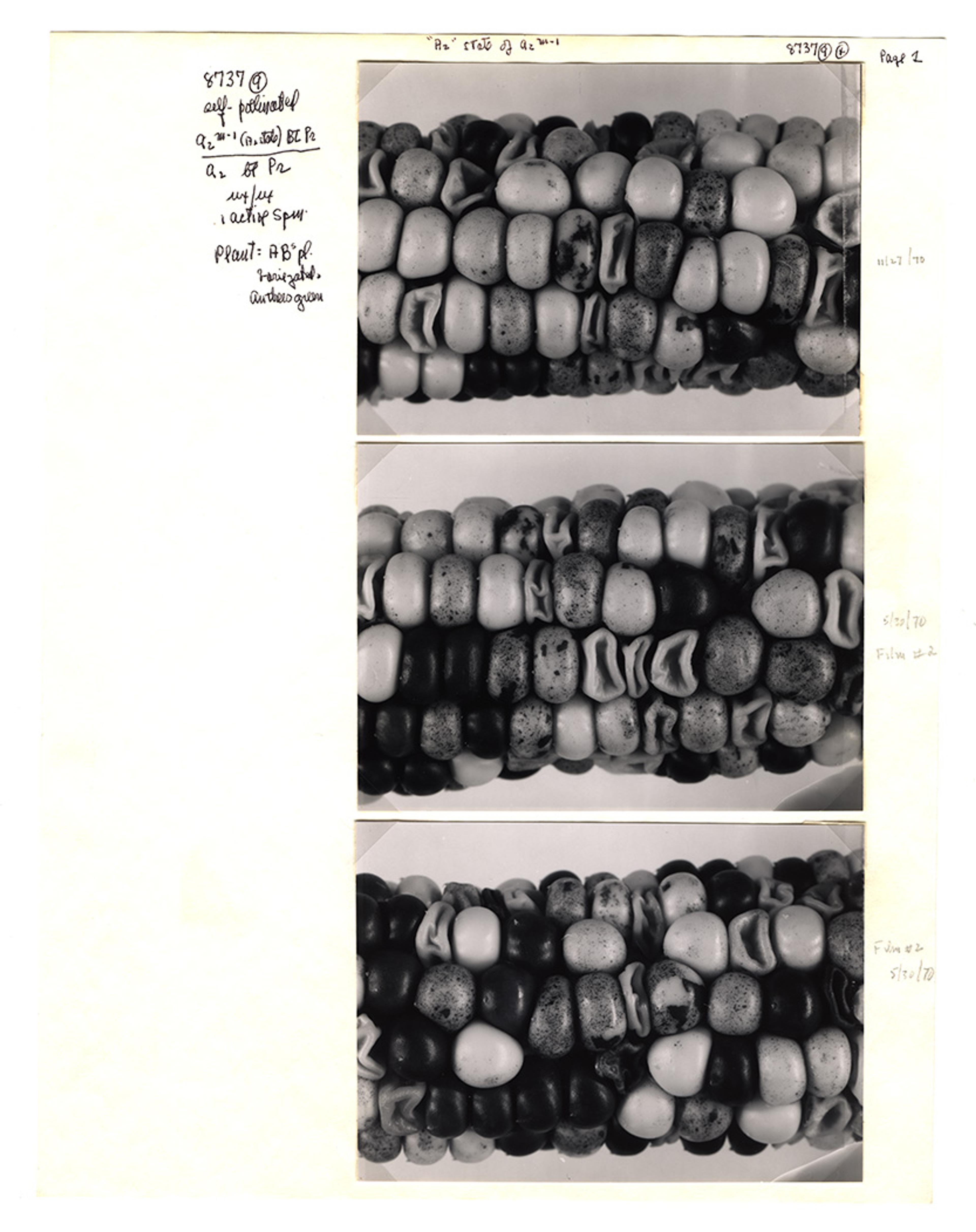

Barbara McClintock at Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island, c1960. Courtesy the Barbara McClintock papers, American Philosophical Society

Even so, one might think, intellectual humility surely has an important role to play. Intellectual humility can temper some of our worst instincts. People often underestimate just how hard it can be to work out the truth. Equivocal, murky evidence is blotted out in favour of the tidy, familiar narrative. Expertise in one domain is illicitly projected onto others. Past failures – fallacious inferences, or snafus of spatial reasoning – are glossed over. Those who value intellectual humility, to their credit, beseech us to be on our guard against these all-too-human tendencies.

This model of the human psyche emphasises our hastiness and hubris. But we are subject to other flaws, too – to cravenness, and self-deception. And when it comes to these other flaws, intellectual humility is prone to function less as a guardrail, and more as an alibi. Simone de Beauvoir’s midcentury masterpiece The Mandarins (1954) dramatises this dynamic. The novel opens as the Second World War is coming to a close. (‘The streets would smell again of oil and orange blossoms … and he would drink real coffee to the sound of guitars.’) It follows a group of Left-wing intellectuals who are trying to make sense of the war’s legacy, and of how they might integrate their political commitments with their personal projects.

About halfway through the book, a mysterious stranger arrives from Russia. He is introduced as a high-ranking Soviet functionary – ‘George’ – who has recently defected to the West; he is said to have smuggled out with him ‘sensational information’ that will be ‘devastating’ for the Soviet regime – a regime in which many of the novel’s characters are profoundly invested. (‘[T]he only chance to see humanity delivered from want, slavery, and stupidity,’ thinks one character, Henri, ‘is the Soviet Union. No effort, then, must be spared to help her.’) George presents Henri and his friend Robert with documents showing that ‘Russian socialism’ – the lodestar of their political hopes – relies on a brutal system of forced labour camps.

Henri and Robert respond quite differently to the evidence. After some initial resistance – ‘George was suspect, Russia was so far away, and you hear so many things’ – Henri comes to believe that the labour camps are real. He realises that the evidence comes from too many different sources – official documents, testimony from American observers as well as deportees – for him to credibly doubt it. Henri realises, painfully, that he can no longer place his hopes in Russian socialism. ‘In Russia, too,’ he thinks, ‘men were working other men to death.’

Both use a pose of humility to hide what is, in reality, just cowardice

Robert responds with more diffidence. He chooses, Beauvoir writes, ‘to doubt’. He insists that it would be irresponsible to judge with only the information to hand, and that nothing has been ‘genuinely established’. Reflecting on his friend’s behaviour, Henri thinks to himself that Robert has taken ‘refuge in scepticism’. Later, when Robert talks over the situation with his wife, Anne, she is initially inclined to disagree with her husband – to think that the evidence they have is decisive, that further enquiry will be otiose, and that Robert should help to publicise the revelations about the camps. But Robert insists that he cannot proceed until he knows more. Anne falls silent. ‘I didn’t insist,’ she records. ‘What right, after all, did I have to protest? I’m too incompetent.’

Of Beauvoir’s trio of characters, Henri is clearly the most admirable. This puts pressure on those who would treat intellectual humility as a virtue. Robert attends to the possibility of error, and to the difficulty of judging complex bodies of evidence. Henri, by contrast, is almost impetuous. Anne takes her peer’s disagreement seriously, and is intensely conscious of the limits of her political expertise, whereas Henri doesn’t care that his old friend Robert has come to a different conclusion. Robert and Anne, then, cleave closer than Henri to the dictates of intellectual humility. And yet, Henri deserves more praise than either.

One might argue that neither Robert nor Anne is genuinely intellectually humble. Rather, they only pretend to be humble. Both use a pose of humility to hide what is, in reality, just cowardice. As such, one might think, neither makes genuine trouble for the idea that intellectual humility is a virtue. Rather, these cases simply show that the virtue of intellectual humility must be married to that of intellectual courage.

It’s not so clear, though, that we can draw a principled distinction between intellectual humility and intellectual cowardice (or, conversely, between intellectual hubris and intellectual courage). We are inclined to think of Henri as intellectually courageous – rather than as hubristic and rash – because he got things right, and to think of Robert as cowardly because he got things wrong. Imagine a version of The Mandarins – and, indeed, a version of history – in which George’s documents were all forgeries: part of an elaborate CIA conspiracy to discredit the Soviet Union. Against such a backdrop, what we were before inclined to assess as Robert’s cowardice looks more like genuine humility. What seemed before, on Henri’s part, like clear-sightedness and nerve, starts to look more like recklessness. The lesson is that it’s hard to isolate our judgments of intellectual character from the results of that character’s exercise within a given context. To judge whether you were being humble (good), or timorous (bad), I will often first need to know whether you ended up with knowledge.

We have reason, then, to be sceptical of the ambitious virtue epistemologist’s claim that we understand what knowledge is via our grasp of the intellectual virtues. Still, that’s compatible with thinking that intellectual humility makes for a genuine virtue, and, as such, that we should aspire to cultivate it.

But what if it turns out that our intellectual icons – our exemplars of the intellectual good life – tend not to be humble? What if it turns out that the growth of knowledge proceeds not via humility, but rather via stubborn pig-headedness? These are not hypothetical questions. A look at the history of science suggests that intellectual humility, far from being a crucial ingredient in intellectual flourishing, might serve to corrode it.

She could look at maize cells and see details of their chromosomal structure that would be invisible to others

Consider the geneticist Barbara McClintock. She became fascinated by genetics while still a student at Cornell University in New York in the 1920s, and she went on to puzzle over the chromosomal structure of maize for decades. After struggling to find a secure faculty position within a university, McClintock spent much of her career at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on Long Island, where she developed a highly idiosyncratic approach to the study of genetics. At a time when many geneticists studied the fruit fly Drosophila – and, later, bacteria – because of their speedy reproductive cycles (Drosophila produce a new generation every 10 days), McClintock stuck with the more traditional maize, taking her time to really get to know each new batch of plants.

‘I know every plant in the field. I know them intimately,’ McClintock told her biographer, Evelyn Fox Keller. Deep, affectionate attention for her objects of study was a hallmark of McClintock’s method. McClintock’s peers were amazed by her perceptual acuity. She could look at maize cells under a microscope and see details of their chromosomal structure that would be invisible to other people. She explained: ‘[I go] intently over each part, slowly but with great intensity.’ She felt herself merge with the chromosomes she examined. ‘As you look at these things,’ she reflected, ‘they become part of you. And you forget yourself.’

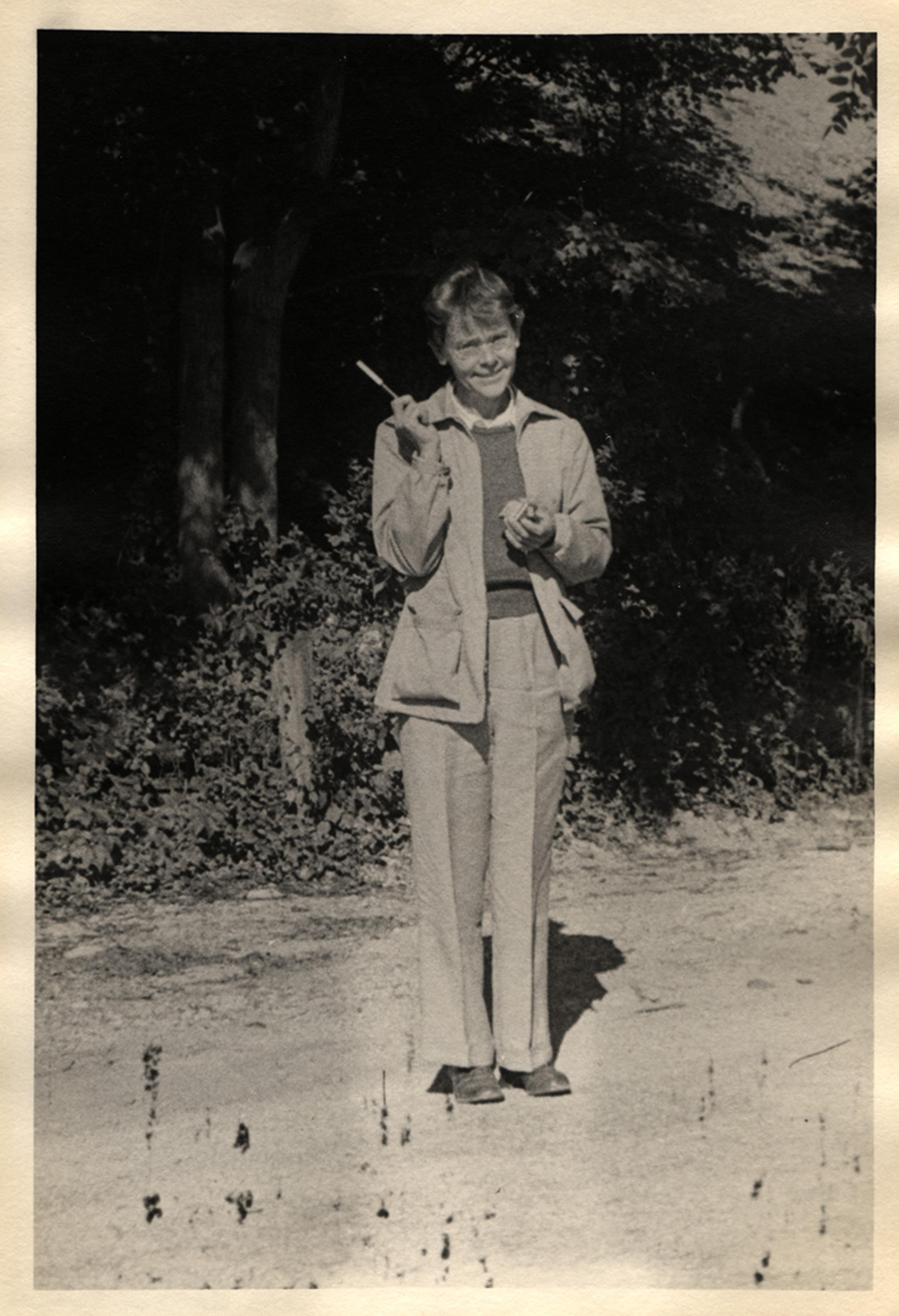

In the early 1950s, McClintock began reporting on results that disturbed her peers. Back then, geneticists tended to operate with two crucial default assumptions. The first was that a gene’s position on the chromosome was fixed. The second was that genes were modular: that a given chunk of genetic information contained a rigid set of instructions that the organism could implement in only one way. McClintock realised that both assumptions were false. She realised that genes could be turned ‘on’ or ‘off’. How an organism will express a given gene is not rigidly determined by that gene on its own, but by how that gene interacts with other genetic units: the ‘controlling elements’ that either activate or shut down the gene’s instructions. Further, these controlling elements do not have a fixed position on the chromosome. Rather, they are able to ‘jump’ between different spots on the chromosomal string. The historian of science Sharon Bertsch McGrayne explains the consequences clearly. Suppose that a controlling element jumps next to a pigment gene and turns it off very early in development. The plant will end up with colourless leaves. By contrast, if the pigment gene is turned off midway through the plant’s development, the plant will end up with streaked or spotted leaves. Two plants might thus start off with exactly the same chromosomes, but have leaves that look very different: one set monochrome, the other dappled.

McClintock’s peers were baffled by her work. When she first presented her ideas, McClintock spoke for an hour at Cold Harbour. She was, McGrayne reports, greeted with a ‘dead silence’. (As anyone who has given an academic talk knows, this is a bad sign.) Harriet Creighton, an important collaborator of McClintock’s, recalled that the talk ‘fell like a lead balloon’. In 1953, McClintock published her ideas, but the paper received little attention. Fellow scientists joked that her project was ‘mad’, or called her ‘an old bag’.

Unperturbed by her peers’ incomprehension, McClintock was deeply invested in her own brilliance

Most people, confronted with such a mixture of hostility and incomprehension, would pause to reconsider their views. They would worry that, if their peers are so bewildered by their claims, then maybe their claims really are bizarre and unfounded. Certainly, intellectual humility would look to have required McClintock to take her peers’ concerns seriously. Yet McClintock ignored her detractors. She decided that publishing was a waste of time, and stopped presenting her work at Cold Harbour.

Barbara McClintock’s microscope and maize samples. Courtesy the Smithsonian National Museum of American History

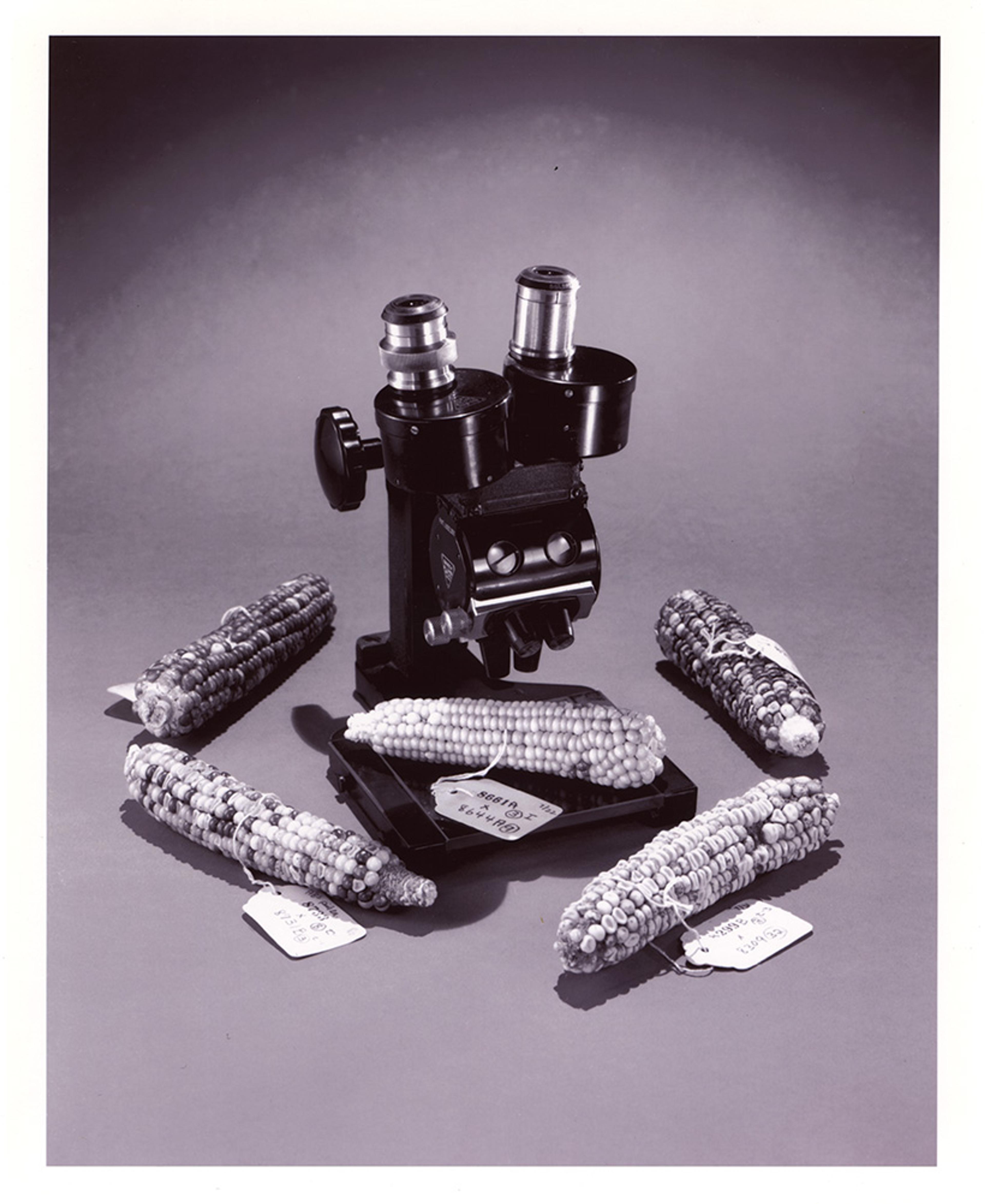

But she didn’t give up on her project. Rather, she continued to pursue her ideas with a relentless focus, embedding her maize plants within an increasingly rich, highly visual structure of meaning. In many ways, then, McClintock’s behaviour was that of a crank. ‘I just knew I was right,’ she later insisted. But McClintock’s crankish single-mindedness paid off. More than 30 years after her disastrous presentation at Cold Harbour, she won a Nobel Prize for her work on mobile genetic elements. It was 1983, and she was the first woman to win the prize for physiology and medicine unshared.

By any plausible metric, McClintock lived an intellectually flourishing life. But she was not intellectually humble. As well as being unperturbed by her peers’ incomprehension, McClintock was deeply invested in her own brilliance. She was proud of her intuitive grasp of her plants. Fox Keller recounts that McClintock was able to predict what she would see in a plant’s nucleus, under her microscope, simply by inspecting the plant in the field. ‘Before examining the chromosomes,’ McClintock recounts, ‘I went through the field and made my guess for every plant as to what [I would see] … And I never made a mistake, except once.’ When, looking through her microscope, McClintock thought that she had made a faulty prediction, she was, she says ‘in agony’. She ‘raced right down to the field’. To her immense relief, she discovered that she had made a filing error: instead of recording the number of the plant she had cut open and examined under the microscope, she had written down the number of the plant adjacent. ‘And then,’ she told Fox Keller, ‘everything was alright.’

Of course, one might think that, although McClintock did live a flourishing life, it would still have been a better life if she had been more intellectually humble. But this is not especially plausible. Had McClintock been more attentive to her potential intellectual limitations, it’s not clear that she could have developed a way of doing and thinking about genetics that was so wholly her own, and which underwrote her ability to see past the dogmas that blinkered her contemporaries. McClintock herself was insistent that her work required a kind of quiet certainty – that the judgments she made required ‘complete confidence’. McClintock, then, serves to illustrate a key dictum of Friedrich Nietzsche’s psychology. In Beyond Good and Evil (1886), Nietzsche argued that even our noblest impulses are thoroughly mingled with our darker, wickeder drives. McClintock’s love of her corn plants and her egotism, her creativity and her caustic obstinacy – all these form a cohesive whole. There’s something facile in the attempt to split them off from each other, to hypostatise the good aspects of her character as separate from the bad.

What are the options for those who want to rescue the idea that intellectual humility is a virtue? One option would be to institute a two-tier system. McClintock, one might say, was a genius. And geniuses can get away with things the rest of us cannot. The traits that underwrite intellectual flourishing for geniuses will not underwrite intellectual flourishing for the masses, because the sort of ‘high grade’ flourishing available to McClintock is simply not available to the rest of us. She flourished, yes, but she can’t serve as a meaningful role model for ‘ordinary’ beings like us.

Delineating intellectual virtues is like prescribing which colours an artist should use if they want to paint well

It is deeply unattractive, though, to split humans into ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ types. But even if we could stomach the inegalitarian division (and I couldn’t), the suggestion is flawed. We’ve all met idiots who think they’re geniuses – idiots who would, given half a chance, identify themselves as belonging to the ‘higher type’. In general, it’s precisely those who would most benefit from a dose of intellectual humility who would classify themselves as standing outside its demands.

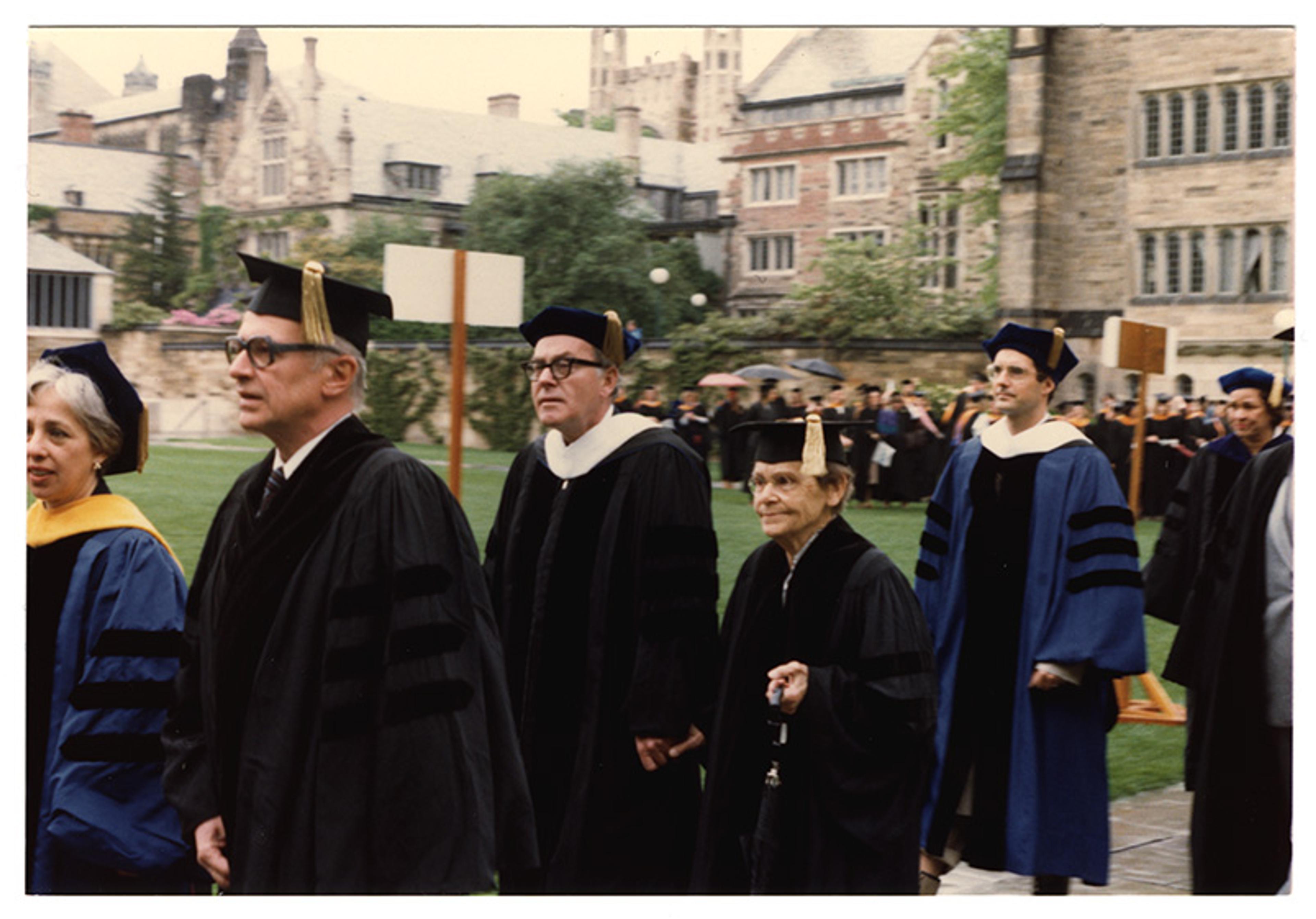

Barbara McClintock receiving an honorary degree from Yale University in 1982. Courtesy the Barbara McClintock Papers, American Philosophical Society

Still, there’s something right in the thought that we shouldn’t start imitating McClintock’s particular traits. We should admire McClintock because she was able to take a highly idiosyncratic bundle of talents and flaws, and fashion it into a knowledge-conducive intellectual personality. That’s a task that each of us faces. But, crucially, our talents and flaws and environments are very different from each other’s. In light of that diversity, delineating intellectual virtues – stable character traits capable of generically underwriting a life of intellectual flourishing – starts to seem like prescribing which colours an artist should use if they want to paint well. Any colour of paint can, in the right hands, be used to create a beautiful painting. Similarly, almost any character trait can, under sufficiently congenial circumstances, serve as a handmaiden to knowledge.

Intellectual humility, then, isn’t a virtue, because there are no intellectual virtues. There are traits that are sometimes conducive to knowledge, and traits that are sometimes not. But there are no general rules about which traits are which, and so there is no way to classify, for all times and temperaments, our intellectual traits as ‘good’ or ‘bad’. The search for intellectual virtues is the search for a rulebook or a recipe: a way to guarantee that we will find ourselves on the right side of truth. But when it comes to the intellectual good life, there are no such rulebooks or recipes; there is no method by which to guarantee against fake news or false confidence. Epistemological anxiety is as old as philosophy itself. It deserves a better rejoinder than the moralistic injunction to be humble.