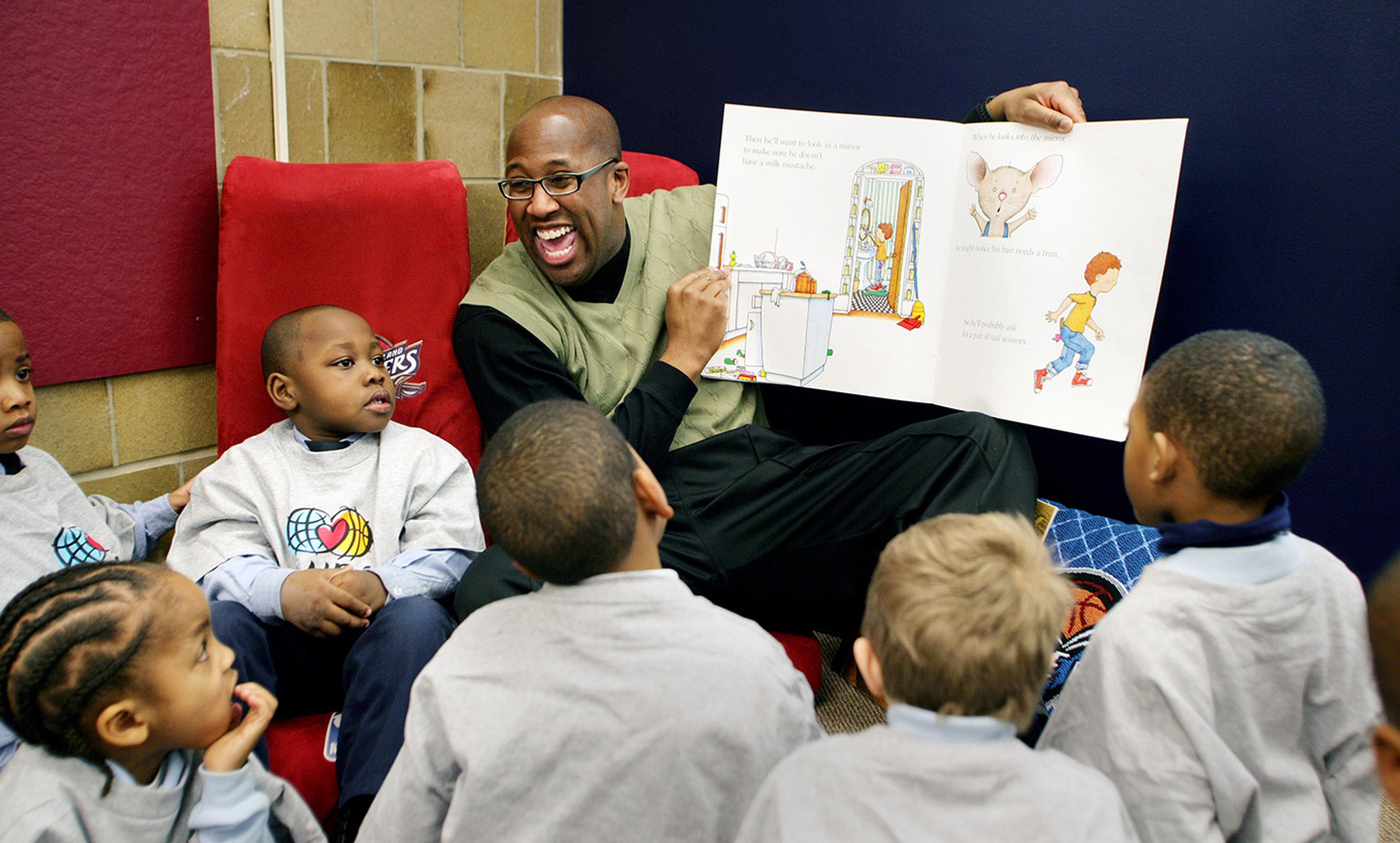

Mike Brown, former head coach of the Cleveland Cavaliers, reads to children at the Cavaliers All-Star Library at the Kenneth Clement Boys Leadership Academy, 12 February 2008. Photo by David Liam Kyle/Getty

In September 1965, an article titled ‘The All-White World of Children’s Books’ appeared in the influential American magazine The Saturday Review of Literature. Its author, the editor and educator Nancy Larrick, noted that African-American children were learning about the world ‘in books which either omit them entirely or scarcely mention them’. In one award-winning volume from 1945, black children were portrayed with bunion-covered feet and popping eyes, living in dilapidated shacks with gun-wielding adults. Meanwhile, white children were ‘nothing less than cherubic, with dainty little bare feet or well-made shoes’, Larrick wrote. After years of complaints, she said, the publisher finally solved the problem by simply removing all black faces from the book.

More than 50 years later, the problem persists. Imaginary black children remain almost as marginalised as real ones, at least in mainstream publishing. In literature, as in life, the belief that children are valuable, vulnerable and in need of protection has mostly been denied to black children in the United States. Black children learn fast that their childhoods have very strict boundaries, in which any small slip or mistake can put their lives in danger, often from police or other agents of the state.

In this context, what children read is more than just frivolous entertainment. It’s an imaginative, safe space in which they can experiment with different modes of selfhood and citizenship. So what does the history of the representations of black children in the US reveal about the cultural tools they’ve been handed, and with which they’ll need to fashion their own lives and futures?

Depictions of black characters in the late 19th and early 20th century tended to promote negative stereotypes. Childhood favourites such as The Story of Little Black Sambo (1899), Tarzan (1912), and The Story of Babar: The Little Elephant (1931) are transparently propagandistic portrayals of Western and white superiority over Africa. In Tarzan of the Apes, Tarzan writes in a note that Jane reads: ‘This is the house of Tarzan, the killer of beasts and many black men.’ For the black child who seeks to identify with the hero but is categorised as the villain, these depictions produce a mental and conscious disconnect.

It wasn’t until the early 20th century that a more positive strand of black children’s literature developed. In 1920, the African-American scholar and activist W E B Du Bois created The Brownies’ Book – the first black children’s magazine, he said, that would help ‘black children to recognise themselves as normal, to learn about black history, and to recognise their own potential’. The Brownies’ Book was one of the first attempts to try to normalise and dignify black childhood.

In the 1960s, children’s books became a powerful ideological tool during times of protest and civil unrest. In The Wretched of the Earth (1961), the French-Algerian writer Frantz Fanon talked about the importance of literary representation as a site of political influence. Fanon believed that black children learned self-hatred and alienation through early contact with the white world, partly because of the storybooks, comics and cartoon images to which they had access. Finding alternative representations was therefore an urgent necessity.

In the civil rights era in the US, black children and teenagers played a crucial role, both symbolically and on the ground. They were participants in marches and meetings, and often subject to violence and imprisonment. But black children’s lives also became politicised in other ways, as activists used literature and culture to galvanise the youth and foster a sense of purpose and pride in their identity. Factions such as the Black Arts Movement tried to create counter-narratives that pushed back against the brutality that white children’s literature inflicted on young black psyches. For example, Virginia Hamilton’s young adult novel Zeely (1967) centres on the realistic, everyday aspects of black childhood. Its 11-year-old black protagonist, Elizabeth, is a smart and strong-willed girl, who becomes intrigued by a tall black woman who lives on a nearby farm. Books such as Zeely represented a watershed moment in culture. They served to counteract previous distortions of black youth, allowing children to develop a sense of imaginative possibility about their own lives, and empowering them as agents of social change.

In the 21st century, black authors have continued the tradition of using literature to rally young people. Often, writers depict black children who are active participants in the struggle for liberation. One example is the picture book Daddy, There’s a Noise Outside (2015), by the community activist Kenneth Braswell. Inspired by the death of Freddie Gray when he was under arrest in Baltimore, Braswell uses children’s literature to discuss protest in black communities. The story begins as a brother and sister wake up in the middle of the night after hearing chanting outside their window, and their parents try to explain the nature and value of protest for black communities. The young characters in the story are learning about the many forms of activism that are accessible to children, which include creating signs, writing letters, participating in protests and organising.

These narratives pay homage to earlier black liberation efforts and give children the tools necessary to understand themselves as actors in the political process. Children’s literature becomes a means of education, offering a safe space for experimentation and a supplement to the organisation of formal movements.

In an opinion piece for The Guardian in 2015, the American young-adult author Daniel José Older wrote: ‘Literature’s job is not to protect young people from the ugly world; it is to arm them with a language to describe difficult truths they already know.’ He added that it’s vital for literature’s creators and publishers not to sit on the sidelines of movements such as Black Lives Matter, where most of the actors are young people.

Children are not just the passive recipients of what they read. They should be seen as active subjects, creating and recreating themselves in relation to the representations that surround them. In this way, literature is an arena in which children can safely play with and develop an understanding of the state, and their role and relationship to it. Children’s literature not only shows how important children have been to black social movements. It also highlights the power of books to rescue childhood from a culture that has dehumanised black children, and denied them healthy and expansive models for growing up.