If you can bear it, go to YouTube and watch a video of a far-Right rally in Europe or the United States. It tends to be a boisterous spectacle verging on outright mayhem – and you, the concerned viewer, might wonder why many of those assembled appear so angry and full of hatred, so receptive to the provocations of a showman-in-chief goading them to expressions of intolerance and violence. What has happened to them, these otherwise friendly, engaging, law-abiding people?

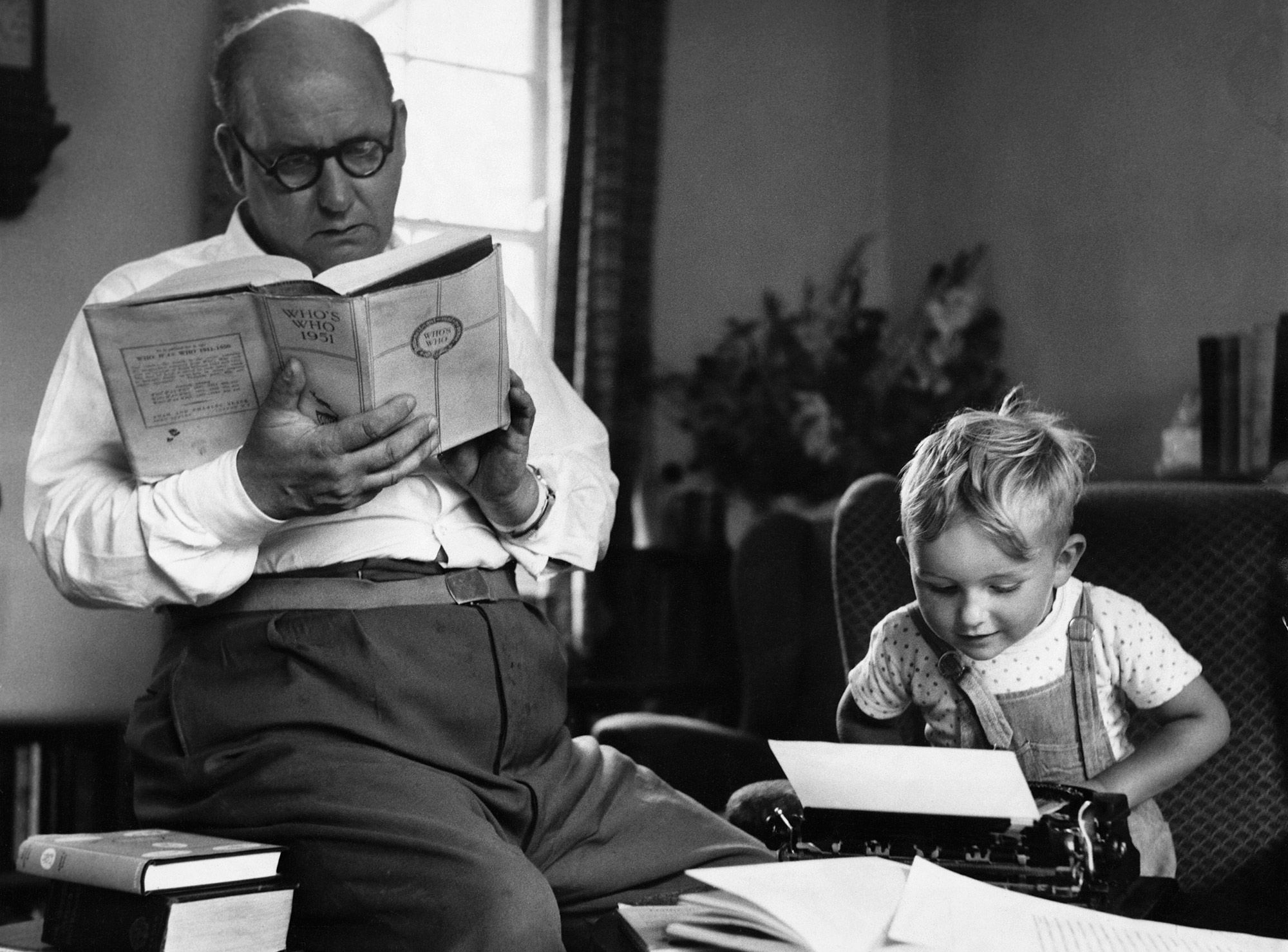

Sigmund Freud wrote Group Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921) with a version of this question in mind. Freud, you say? He’s dead, outdated and irrelevant, critics assert, a theorist of the late-19th-century bourgeois mind with little to say to our sophisticated modern selves. But I disagree – in fact, I’d argue that aspects of his work are more relevant than ever.

In Group Psychology, Freud asks why crowds make a ‘barbarian’ of the ‘cultivated individual’. Why are the inhibitions enforced by social life so readily overwhelmed by all that is ‘cruel, brutal and destructive’ when we join together with others? And why does the crowd need a strong leader, a hero to whom it willingly submits? The crowd – which is, after all, just an evanescent massing of humanity, a gathering that will quickly disperse once its task is finished – is oddly ‘obedient to authority’. It might appear anarchic, but at bottom it’s conservative and tradition-bound.

Freud argues that neither suggestion nor contagion – the idea that I am impelled to do what you do, to imitate you – can account for the paradoxical character of the crowd as both powerful and submissive. Rather, he proposes, it is love and all the emotional ties through which love is expressed that bind people together in a crowd. This might seem counterintuitive, in light of the crowd’s passionate anger. But it’s worth following Freud here.

First, this Freudian love is no sentimental thing. It encompasses a broad range of feelings, from self-love (or narcissism) to ‘friendship and love for humanity in general’ to the intensity of sexual union. Freud argues that it is these so-called ‘libidinal ties’ – ties fuelled by sexual energy – that distinguish a group from a mere collectivity of individuals. This applies regardless of whether the crowd is spontaneous and short-lived (like a rally) or institutionalised (like the army or the church). Freud is realist enough to acknowledge that manifestly loving, intimate relations among people are often tinged with hostility. You need only consider the ‘feelings of aversion’ that exist between husband and wife, or indeed feelings that characterise other long-lasting relationships, such as between business partners, between neighbouring towns, or on a grander scale between south and north German, Englishman and Scot. Love and hate are closely related.

But the hostility that runs through relations among intimates pales in comparison with the aggression we direct toward strangers. There, our ‘readiness for hatred’ is everywhere evident. So, as Freud sees it, it’s all the more striking that these antipathies vanish in the crowd: ‘individuals in the group behave as though they were uniform, tolerate the peculiarities of its other members, equate themselves with them, and have no feelings of aversion towards them’. The crowd unites as it gives vent to hateful sentiments. This seems plausible to us now; hatred directed at the Other has long proven a powerful source of solidarity. But Freud also sketches a less immediately plausible scenario: members of the collective forgo the ordinary pleasures of rivalry and dislike among themselves, and instead adopt en masse an ethos of equality and fellow-feeling. (A 2004 translation renders Freud’s title not Group but Mass Psychology, truer to Freud’s original Massenpsychologie.)

The mass does this by directing its passions to the leader, an outsider whom it treats as a superior. This leader’s pull is powerful enough to neutralise the intra-group hostilities, Freud says. Conjuring up a remarkably contemporary scene, he asks us to imagine a ‘troop of women and girls’, besotted by a musician and jostling round him after a performance, seeking his favour and perhaps a snippet of his ‘flowing locks’. Each seeks to prevail over the others, but they all know that they’re better off in renouncing their individual, rivalrous desires for the star’s love and instead uniting around their common love for him. They don’t pull out each other’s hair; each gets something of what she wants – the opportunity to pay homage to him and to feel enlivened in doing so. As at a rock concert, so in social life more generally. Identification with the leader trumps envy among individuals, knitting the group together.

There’s definitely some sleight of hand here; Freud isn’t interested in how the rock star’s fans decide to stop fighting among themselves but only in the fact that they do. His account is stronger descriptively than analytically. But his notion of identification is still a powerful tool for dissecting mass behaviour. For Freud, a successful leader invites the crowd to identify with him, which in his usage involves a big dose of idealisation. Think here, Freud says, of the little boy’s identification with his father – the boy wants to grow up and be like him. Identification can also be based on the perception of commonality with someone else, the sense that there’s something shared between us. The leader is at once larger-than-life and familiar, bigger than I am and just like me. He’s heroic and at the same time recognisably human.

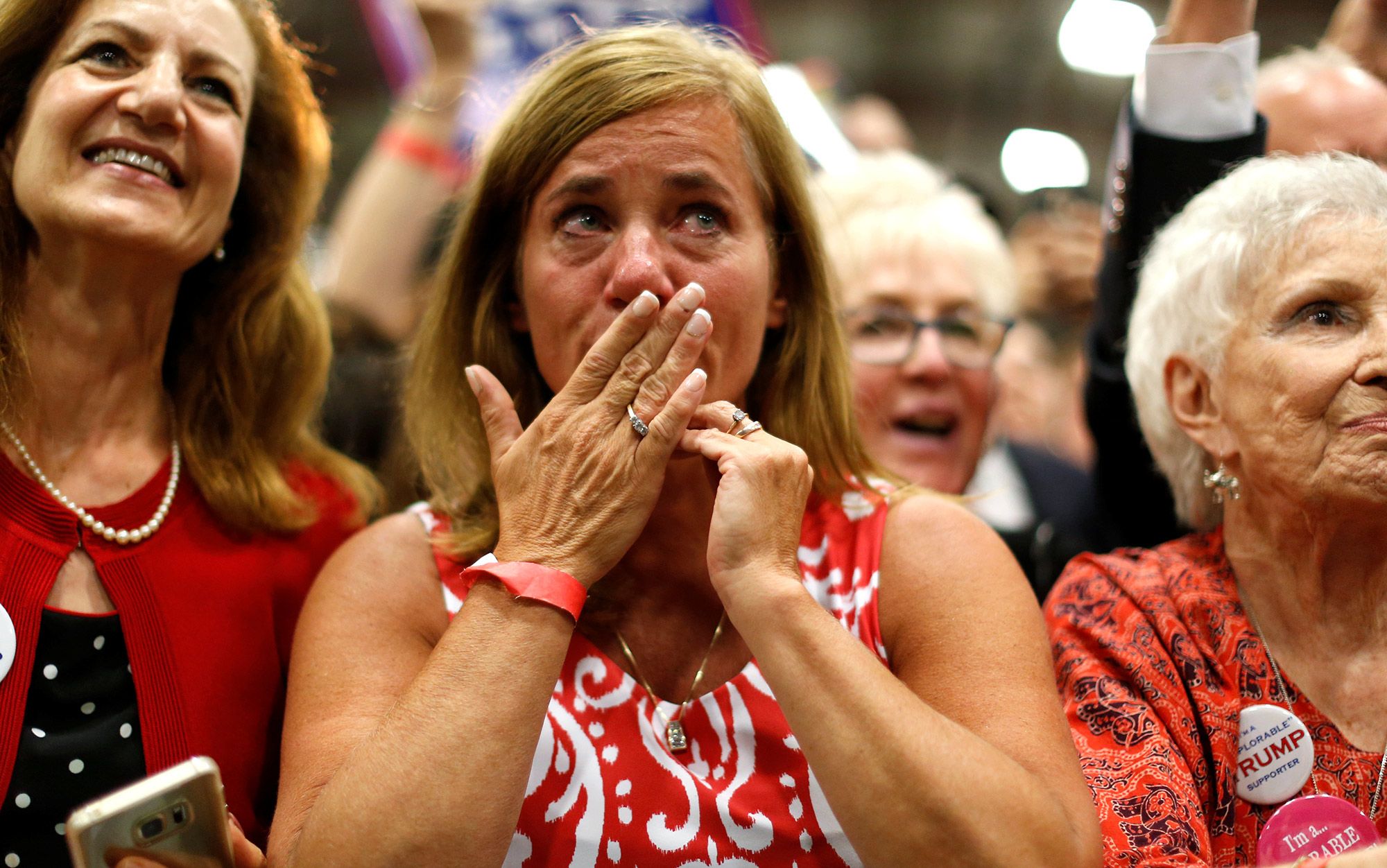

Today, these dynamics converge in the figure of Donald Trump and his acolytes. Like Freud’s exemplary leader, Trump invites identification. In the eyes of his supporters, he’s both an idealised hero capable of extraordinary feats (‘Make America Great Again!’), but also an ordinary guy just like one of them. His gilded lifestyle is aspirational but his tastes are accessible (a ‘beer taste on a Champagne budget’, as one commentator put it in The Guardian). Trump’s roiling resentments, fears and disgusts are openly on display, inviting and authorising imitation. And he is a master of playing to the crowd’s desire for transcendence, deploying his own grandiosity to make them feel part of something bigger than themselves. First, he points to the crowd’s humiliation: ‘We’re tired of being the patsy for, like, everybody. Tea party people… You have not been treated fairly. You talk about marginalising.’ Then he declares himself their tribune: ‘At least I have a microphone where I can fight back. You people don’t!’ Finally, he shares his power with them, telling the crowd: ‘You don’t know how big you are. You don’t know the power that you have.’ Trump and the crowd are one; the identification is complete.

Elizabeth Lunbeck is a professor of the history of science at Harvard University. Her latest book is The Americanization of Narcissism (2014).