The six city-states on the Arab side of the Persian Gulf, each formerly a sleepy, pristine fishing village, are now all glitzy and futuristic wonderlands. In each of these city-states one finds large tracts of ultramodern architecture, gleaming skyscrapers, world-class air-conditioned retail markets and malls, buzzing highways, giant, busy and efficient airports and seaports, luxury tourist attractions, game parks, children’s playgrounds, museums, gorgeous beachfront hotels and vast, opulent villas housing fabulously affluent denizens. The six city-states – Dubai and Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Manama in Bahrain, Dammam in Saudi Arabia, Doha in Qatar, and Kuwait City in Kuwait – grew into these luminous metropolises beginning in the 1970s, fuelled by the discovery of oil and gas, an oligarchic accumulation of wealth, and unconditional grants of political independence from the United Kingdom, the former colonial master of the region. Thereafter, the family-run polities that took control of these city-states began to attract huge amounts of financial capital from all over the world. Abu Dhabi, the capital of the UAE, has been described as ‘the richest city in the world’, with wealth rivalling that seen in Singapore, Hong Kong or Shanghai. Like those cities, Abu Dhabi is swimming in over-the-top affluence. According to a 2007 report in Fortune magazine, Abu Dhabi’s 420,000 citizens, who ‘sit on one-tenth of the planet’s oil and have almost $1 trillion invested abroad, are worth about $17 million apiece’.

The Persian Gulf has a venerable history, stretching back to ancient times. It has always been a cosmopolitan and diverse centre of wealth and commerce. For nearly 1,000 years, Dilmun, a Bronze Age Arabian polity based in what is today Bahrain, controlled the trading routes between ancient Mesopotamia and the Indus river valley. During the Abbasid caliphate, a 500-year-long Islamic empire based in Baghdad, mercantile entities in Basra and al-Ubulla, at the head of the Gulf, dominated trade and commercial links with East Africa, Egypt, India, Southeast Asia and China. One could buy anything in this trade, including giraffes, elephants, precious pearls, silk, spices, gemstones and very expensive Chinese porcelain. Omani Arabs, who periodically controlled the maritime entrance to the Gulf at the Strait of Hormuz, were known as the ‘Bedouins of the Sea’. They came to control the trading routes with East Africa, transporting spices, precious stones and many other luxury commodities.

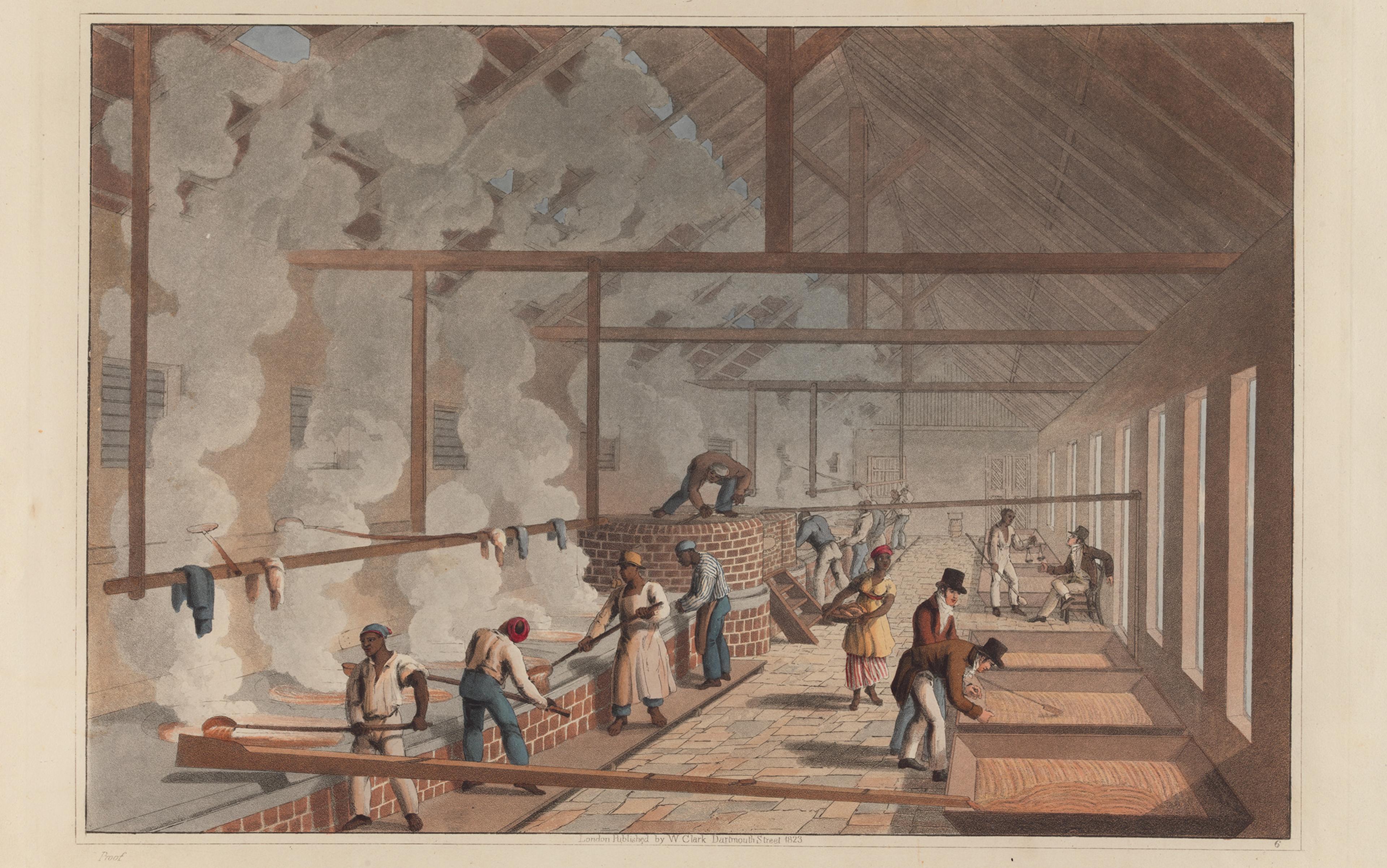

Slavery and slave trading formed a major part of this commercial history, particularly after the advent of Islam. Africans, Baluchis, Iranians, Indians, Bangladeshis, Southeast Asians and others from the Indian Ocean littoral were steadily and involuntarily transported into the Gulf in increasingly large numbers, for work as domestic servants, date harvesters, seamen, stone masons, pearl divers, concubines, guards, agricultural workers, labourers, and caretakers of livestock. Historians have noted that there was a great upsurge of slave trading into the region in the 18th and 19th centuries, during the heyday of the Indian Ocean slave trade. Many Persian Gulf families became very wealthy as a result of this upsurge. This is the backdrop for what turns out to be a very ugly and sad aspect of the spectacular rise of contemporary social orders in the six Gulf city-states. Each is an example, and perhaps the only examples existing in the world today, of what the sociologist Moses Finley (1912-86) called a ‘genuine slave society’.

Finley is one of the most important scholars of slavery. His book Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology (1980) has had a profound effect on how scholars across the social sciences understand and study slavery. He argued that the slave, in contrast with the ordinary labourer, is an income-producing commodity – a species of property to be bought, sold, traded, leased, mortgaged, gifted and even destroyed, like other commodities – and this special status permitted exploitation of the slave in ways that were unique and central features of many societies. He divided these societies into two categories: those societies that could be described as ‘societies with slaves’ and those that he described as ‘genuine slave societies’, that is, those where slavery was an essential aspect of the society’s self-definition. The genuine slave society can’t function without the presence and work of its slaves. Some argue that the core definition of slavery has changed in contemporary sociological theory and practice since Finley’s time. This change recognises a phenomenon commonly described as ‘modern slavery’. I disagree. Applying Finley’s model to contemporary Persian Gulf societies, I argue that this change, indeed expansion, in the definition of slavery makes no difference in the analysis, and might make it even easier to apply the model to the Persian Gulf city-states. They are just as much genuine slave societies, using Finley’s analysis, as were the ancient societies he described.

In reporting on slavery today in the Gulf city-states, I rely on statistics from a number of sources. Inevitably, some of these statistical sources are more reliable than others, but I have made an effort to use sources that have been vetted or are generally accepted as the product of sound and reliable methodologies. I think that the statistics employed in this essay are as accurate as can be obtained under the circumstances. As every reader knows, however, no set of statistics is completely foolproof, and the Persian Gulf governments obviously have an interest in promulgating statistics that are favourable to them.

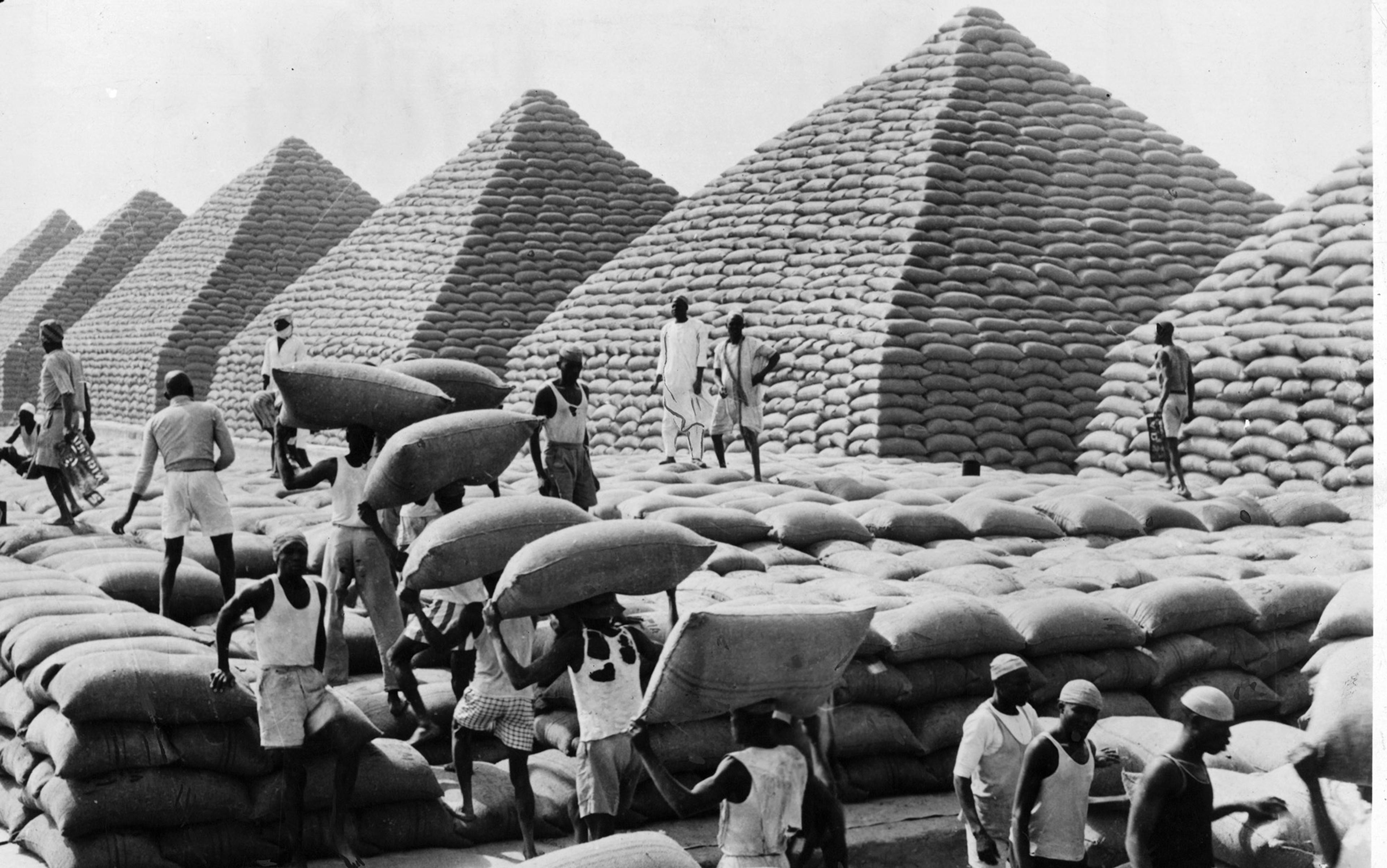

In the region, migrant workers make up a large percentage of the population – for example, in the UAE and Qatar, they constitute around 90 per cent, in Kuwait, this is around 66 per cent, and in Saudi Arabia, around 33 per cent. These labourers have few rights in the legal systems of the city-states, and a great majority work in very dangerous circumstances on huge construction sites, frequently risking death or serious physical injury from hazardous worksite conditions, including long hours without breaks, debilitating heat approaching 50 degrees Celsius or 122 degrees Fahrenheit, a lack of elementary safety precautions and the absence of competent supervision. Reputable labour organisations have reported that one or two workers die on these construction sites every day and, in Qatar, which is preparing to host the 2022 FIFA World Cup, more than 4,000 migrant workers will die in workplace accidents on FIFA projects before the event takes place. No other construction project in the world even comes close to such rates of death.

A construction worker in Dubai earns about AED106,000 (US$28,000) a year compared with the AED258,000 (US$70,251) per capita yearly prevailing wage in the city. The same is generally true in each of the other city-states. Construction workers are housed in squalid dormitories. In these work camps, 20 to 30 men can end up sharing one bathroom, with eight or more sleeping in the same room. Passports and other travel documents are confiscated upon arrival and workers essentially spend all of their waking hours on the construction site; they are transported to and from the sites each day with little or no chance to see or enjoy the city they are helping to build. Those who don’t work on the construction sites can be found working as domestic servants throughout the region, often completely hidden from view, and others are employed in commercial and industrial enterprises, working as drivers, cleaners, caretakers, security guards, carpenters, plumbers, pipefitters, stone masons, and in a variety of other workplace occupations.

All of these migrant workers are from locales outside the Persian Gulf. None are citizens of any of the Persian Gulf nations, and there is no path to citizenship or even to permanent residency for any of them. Social and legal discrimination against them is openly tolerated and widespread. They often end up in the Persian Gulf after responding to deceptive and misleading advertising in their home countries, causing them to either pay large sums or to borrow such sums from employment agents to secure employment in the Gulf and to pay for their transportation, housing and food. When they arrive, they learn that, based on the value of their wage in real terms, it will be nearly impossible to pay off any debt they have incurred or replenish the sums they have expended. This encourages their employers to withhold, delay or simply not pay wages, coercing the workers to remain on the job, sometimes for a lifetime. In the meantime, migrant workers don’t have the same rights to educate their children, change their employers, pursue education or training, enjoy leisure time, or partake in any of the other pleasant amenities of life that Persian Gulf citizens take for granted. It’s also clearly a race-based system. Almost all of the migrant workers I have described are brown-skinned or even darker. Skin colour is therefore a marker for their low social status and an invitation by local citizens and officials to discriminate against them.

The kafala regulations bind the worker to the employer in the same way that slaves are bound to their owners

Domestic workers, also usually darker-skinned women from Bangladesh, the Philippines, East Africa and other locales, come to the Gulf under similar circumstances. They’re frequently not paid, subjected to delayed wages or underpaid for their work. They’re required to work long hours with no time off, and can’t get medical or dental care. They’re subject to sexual abuse by employers and other forms of violent exploitation and, like construction workers, they aren’t allowed to venture away from the worksite without permission of the employer. Punishment for misdeeds can be extreme because there is little or no regulation of domestic employment by the authorities. Many women migrants are deceived or coerced into working in brothels and other sexually exploitative circumstances. Dubai has thus become famous worldwide for the availability of young women for sex.

The kafala (sponsorship) system binds all low-status migrant workers in the Gulf to their employers. Generally, the kafala system requires the worker to obtain the employer’s permission to travel or leave the worksite to look for other employment. Regulations require a minimum of two years of work for the sponsor (kafeel) before such permission will even be considered. This encourages widespread wage suppression and conspiracies to deny such permission. Such ‘labour bans’ effectively bind the worker to the employer for a long period of time. More significantly, a worker can’t get an exit visa from the government without permission of the kafeel. According to recent reports from Al Jazeera and the Middle East Eye online news portal, employers frequently use the kafala system to force workers to endure abuse. If workers reject employers’ demands, the employer can accuse them of vague crimes or breach of contract. Being out of compliance can result in deportation without pay, a significant fine or a prison sentence. The kafala system effectively doesn’t allow workers to dispute non-performance of the employment contract or lodge any serious complaint against their employers. The system thus places a worker at the total mercy of his or her employer. The kafala regulations bind the worker to the employer in the same way that slaves are bound to their owners. Employers of migrant labourers in the Persian Gulf under the kafala system are therefore, effectively, slaveholders.

It should be noted that, as this article goes to press, the Saudi Arabian government has determined that it will bring significant reforms to its kafala labour-regulation system, beginning in 2021. The Saudis claim it’s an abolition of the system. Labour activists assert that, while it’s a significant step, it isn’t an abolition, and that potentials for continued systemic abuse remain. Other Persian Gulf governments are also beginning to enact badly needed reforms in the kafala labour-regulation system. These reforms are clearly not an abolition of the system and time will tell what effect they have.

When Finley devised his model for understanding slave societies, proposed and developed in a series of publications beginning in 1968, he broke new ground in the study of slavery. Prior to that time, the scholarship on slavery and slave trading focused on the dialogue between scholars influenced by Marxism and those in the tradition of Max Weber and Karl Polanyi. The Marxist tradition viewed slavery as one of the necessary stages in the class struggle for control of the means of production, while scholars influenced by Weber and Polanyi saw the rise of slavery as a manifestation of anthropological, religious, jurisprudential, military and sociological drivers of the triumph of modern and bureaucratic urban society over the nuclear family. Finley observed that neither approach was satisfactory, although he tended to agree with Weber’s view, which emphasised the fact that slavery would periodically rise and fall in history, rather than the Marxist view, which predicted a progressive elimination of the institution. A historian of the ancient Greek world, Finley was probably the first to observe that both slavery and freedom advanced hand-in-hand together in the ancient Greek city-states. This insight served Finley to great advantage in his book Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology, including his crafting of the essential distinction between a ‘society with slaves’ (most societies in human history) and a ‘genuine slave society’.

It’s important to note that the modern Persian Gulf city-states have much in common with ancient Greek city-states. I refer to the Persian Gulf metropolises as ‘city-states’ because, like the ancient Greek city-states, they are semi-sovereign or sovereign cities that completely dominate the realms that surround them, economically, socially and politically. On the issue of slavery, Finley’s contributions were an extremely important set of observations. As David Brion Davis, the preeminent historian of American slavery, observed, the correct study of slavery is ‘implicitly connected with some of the greatest problems in the history of human thought’.

In Ancient Slavery and Modern Ideology, Finley concluded that there were only five truly genuine slave societies in human history – Greece, Rome, the Caribbean, Brazil and the American South – and all others were simply societies with slaves. He took a holistic approach and identified the following markers as foundational to any genuine slave society:

- slaves must comprise a significant percentage (greater than 20 per cent) of the larger population

- slaves must be essential to the production of economic surpluses on behalf of elites in the genuine slave society

- slavery must be locatable as a ‘central’ cultural and economic institution in any genuine slave society.

Finley’s positing of slave societies changed the approach that historians, sociologists, anthropologists, economists and other scholars took in analysing both historical and contemporary forms of slavery. The model certainly has flaws. It’s categorically imprecise and relies, perhaps too extensively, on a Western European view of the differences between slavery and freedom. Yet, it also created a powerful normative paradigm that, in the words of the historian Noel Lenski, established a ‘macabre hall of fame’ that all societies must seek to avoid. There are several other aspects of the model that Finley mentioned only in passing that add to its power as an identifier of a genuine slave society. Two deserve special mention here because they’re relevant to the Persian Gulf societies.

Migrant labourers make up a majority of the inhabitants of each city-state, yet have no role in their governance

First, Finley observed that in all of the slave societies except Rome, race and ethnicity played a predominant role in determining who was enslaved. This is obvious in the case of the western hemisphere systems, but it was also true of ancient Greek slavery. The Greeks tended to acquire their slaves almost exclusively from non-Greek sources. Indeed, Finley insisted that, in a genuine slave society, slaves inhabited an ‘outsider’ status or ‘otherness’ that was a sine qua non of the social construct of the society. Secondly, he observed that, in slave societies, no matter what, the slave is always answerable with his body and through violence. Violence is a central feature in the creation of the genuine slave society, whether it be by warfare or slave-raiding, or by legal regimes that don’t protect the slaves from homicide and other forms of violent assault. Both these aspects – racial and ethnic markers for slavery and the predominant role of violence – also apply to migrant labour in Persian Gulf societies.

In all the Persian Gulf city-states, low-status migrant labourers constitute an overwhelmingly large percentage of the population. Their presence is not just a ‘significant’ percentage of these populations; they make up a majority of the inhabitants of each city-state, yet they have virtually no role in their governance. Secondly, low-status migrants are the essential producers of economic surpluses in each society, whether it be through the construction of large, important edifices that bring great benefit and wealth to users and residents, or as creators and movers of goods and services in these societies, including transportation services, leisure services, domestic services, and other essential items. Lastly, the organisation and employment of low-status migrants in virtually all economic and cultural aspects of the six Gulf city-states are essential to the success of each of the societies. Without their kafala system, these societies would collapse, as the Persian Gulf citizenry is incapable of sufficiently manning the levers that enable these societies to flourish. Finley also focused on ‘kinlessness’ as a marker of the genuine slave society. To some extent, the Persian Gulf systems don’t completely sever relationships between slaves and families, as the systems in Greece, Rome and the western hemisphere did. This is indeed a notable difference but not enough to overturn the overwhelming evidence that Persian Gulf societies are genuine slave societies.

An intelligent and observant reader might ask: ‘But what about the definition of slavery?’ The employment relationships seen in the Persian Gulf aren’t the kind of property-based relationships that Finley wrote about, where slaves were owned, bought and sold, inherited, gifted, leased and financed, like chattel, in markets and other circumstances. This is undoubtedly true but we must also recognise that there are human relationships today that are the effective juridical equivalent of chattel slavery, perhaps best described by the sociologist Orlando Patterson as ‘social death’. In such a situation, the social and legal disadvantage of the labourer is so great that it makes no difference whether the legal system enforces a classical property relationship or not. The person is, in practice, enslaved because all of indicia of the classical property relationship (ownership and control) exist in fact.

One last point. Davis and the legal scholar Robert Cover both observed that there’s a direct relationship between homicide and slavery. We see this when we peruse the literature describing the transportation of slaves in the transatlantic, trans-Saharan, Silk Road and Indian Ocean slave trades. In some cases, the death rates of transported slaves exceeded 30 per cent. Indeed, the presence of high rates of homicide and unexplained death among certain populations in ancient and early modern societies was a clear marker of slavery. We see high rates of homicide and unexplained death among the low-status migrant-labourer populations in the Persian Gulf as well.

Perhaps the best documented evidence of this are the assessments of conditions affecting workers from Nepal. A recent report indicated that at least 1,400 Nepali workers have died on construction sites for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar, and the rate of death continues at about 150 workers a year. The International Labour Organization has also issued a report showing an alarmingly high rate of death among otherwise healthy Nepali migrant workers, particularly in Saudi Arabia, Oman, Bahrain and Kuwait. The death rate in Saudi Arabia was significantly higher than the death rate in Malaysia, and almost at the same level as Malaysia in absolute numbers, even though much greater numbers of Nepalis travel to Malaysia for work. There are similar numbers for other Persian Gulf countries. The estimated death rate for Nepali workers in Saudi Arabia between 2008 and 2015 was 2.26 per 1,000 workers. The rates for Bahrain, Oman and Lebanon were even higher, being reported at 2.60, 2.40 and 2.86 respectively. These rates should be contrasted with lower rates of death in Malaysia, at 1.72, and at 1.61 in South Korea. It appears that the rate of death for Nepali migrant workers in the Persian Gulf hasn’t diminished, and many of the deaths are unexplained. Many of the unexplained deaths are young women, as they are often the victims of horrific sexual abuse and extreme working conditions in domestic work occupations.

Each year, about 1,000 Nepalis who leave Nepal in good health to work abroad die in a labour-destination country; 97 per cent of these deaths occur in the Persian Gulf. As only about 50 per cent of Nepali labour migrants travel to the Persian Gulf for work each year, this number is far out of proportion to the number of Nepalis working in the region. Further, most of the workers are young, with no pre-existing history of disease or vulnerability. The fact that many of these deaths are unexplained caused the Supreme Court of Nepal to recently issue a mandamus (an order for a litigant, usually a government official, to do a ministerial act) requiring the government to perform post-mortem examinations on all the bodies of Nepalis who die while working abroad and whose bodies are returned to Nepal. In many cases, bodies of workers aren’t returned to relatives for months because of interminable bureaucratic delays in getting the bodies released in Gulf countries.

If there is to be true abolition in the Persian Gulf, all of the markers of slavery must be eliminated

Recently, a persistent and steady stream of newspaper reports has described strange and suspicious deaths, including homicides, of low-status Persian Gulf migrant workers. In one report, the Philippines government decided to prohibit Filipino migrant workers, mostly women, from travelling to Kuwait after the body of a Filipina domestic worker was found in her employer’s abandoned home freezer, and the ambassador of the Philippines to Kuwait said that in 2017 he received almost 6,000 complaints concerning the abuse of Filipino workers. It’s said that the embassies of India, Sri Lanka and the Philippines have established shelters in Kuwait for their citizens, almost all women, who have run away from places of domestic employment because of fear of sexual and other violent abuse from employers.

In another case, an Ethiopian maid climbed out onto a seventh-storey window ledge, reportedly to escape from her employer. Rather than rescuing her maid, the employer filmed the incident and the maid fell, suffering injuries, including a broken arm. Cases of employer abuse and neglect occur frequently, and many homicides and other suspicious deaths go unreported or are covered up by the authorities. Africans come in for particular mistreatment. The non-reporting and covering-up of deaths of Africans resembles how authorities have long misreported or covered up police killings of young Black men in the United States.

A statement from the International Trade Union Confederation, made on 30 August 2020, reports that the government of Qatar has ordered a 33 per cent increase in wages for migrant workers and a relaxation in certain kafala regulations. Employers have been given six months to comply with the changes, or face sanctions from the government, including potential suspension of the right to do business in Qatar. Critics say that the changes only scratch the surface. The UAE has also enacted some changes in its regulation of migrant labour conditions, including the offering of instruction to employers on racism, diversity and inclusion. Critics similarly charge that the changes are only designed to improve the image of the UAE abroad. Saudi Arabia now claims that it will abolish its kafala labour system in 2021.

But these changes don’t alter what Finley taught us to describe as a ‘morally reprehensible system of human exploitation’ – six very modern and very genuine slave societies. If there is to be true abolition in the Persian Gulf, all of the markers of slavery that I have identified, particularly the racialisation of labour and rampant worker abuse and exploitation, must be eliminated. I am pleased to report the unveiling of the website Ijmāʿ on Slavery, which is seeking the declaration of a consensus among Islamic scholars that slavery and slave trading are illegal under Islamic law. Each of the city-states that I have identified is run by Muslim governments. I urge Muslim scholars in these communities to join the consensus on the illegality of slavery so that this ‘morally reprehensible system of human exploitation’ in the Persian Gulf city-states is abolished.