On one of my first visits to West Africa, more than 20 years ago, I went to the Fuuta Djalon (also known as Fouta Djallon) mountains of Guinea-Conakry. These beautiful mountains range across high waterfalls, cliffs and lonely paths leading from one village to another over high plateaux. Many settlements can be reached only by foot. In the colonial era, being sited a long way off the roads was a good means of protecting a community from being corralled into forced labour groups by the French colonial police. But in the preceding century, during the era of the abolition of the slave trade, keeping a low profile was also a wise approach.

In that 19th century, the Fuuta Djalon was home to one of the most powerful states in West Africa, a theocratic Islamic state founded in c1726. Fuuta Djalon’s capital at Timbo was ruled by Almamis (or commanders) with a political reach stretching to modern Guinea-Bissau and Senegal in the north, Sierra Leone in the south, and modern Mali to the east. The wealth of Fuuta derived initially from slave-raiding the neighbouring animist peoples – Jalonké to the north, Baga and Susu to the west, towards the Atlantic coast. However, from the beginning of the 19th century, the potential of slave-raiding diminished as the British campaign against the slave trade began after 1807. Freetown in neighbouring Sierra Leone became the centre of Britain’s Royal Naval West Africa Squadron, which patrolled the Atlantic looking for slaving vessels whose cargo would be taken to Freetown and ‘liberated’, forming the nucleus of Sierra Leone’s Krio communities. But this didn’t mean that slavery disappeared in West Africa with abolition: in fact, the prevalence of coerced labour increased, as the locus of production for the global commodities trade expanded to include West African plantations of groundnuts and palm oil.

One of the major sites for this kind of transformation was the Fuuta Djalon. And one morning, as I walked with my guide Abdoulai, and we left his village along a single-file track and climbed a hill to a neighbouring settlement, he turned and whispered to me: These people are the slaves of my village. What did he mean by this, I asked? The ancestors of these villagers had worked for his ancestors: his ancestors had accrued the wealth, and perhaps that was how, a century or more later, it was Abdoulai who had been able to raise money and leave to try his luck at working in distant Dakar, in Senegal. It turned out that, in the Fuuta Djalon, relations of dependence and power hadn’t been erased by French colonial rule in remote reaches of the mountains. Historical memories died hard: two centuries on, the impact of the abolition of slavery on reshaping local economies and relationships endured.

It’s one of the many privileges of being a historian of West Africa to be able to expand the frame of what counts as ‘research’ in ways such as this. With very few state archives on the continent stretching back for centuries, human experience and interaction is a vital part of understanding history, as stories, music, folklore and cuisine are all an important part of the historical record. With COVID-19 unravelling so many aspects of communities, grasping how human interactions beyond the screen are vital to shaping our understanding of ourselves and our societies has never been more important; I have found myself revisiting moments such as this in my own historical training, trying to understand how the process of globalisation facilitated a historical consciousness that might already be a relic of the past.

In the case of West Africa, the abolition era was central to the formation of historical consciousness. It was an era of the rewriting of history in the region, as revolutionary change saw old texts appropriated for new ends with interconnected revolutions overthrowing complacent aristocracies. Most of these movements were grounded in a theology of Islamic reform that swept across West Africa from northern Nigeria to Mali and southern Senegal in the first half of the 19th century. These currents arose to challenge the power of decaying aristocracies, many of which had grown rich from the slave trade. In northern Nigeria, the Hausa city states collapsed and were replaced by the Sokoto Caliphate founded by Shaihu Usman dan Fodio. In Mali, a new allied theocracy arose at Massina, and in Senegambia a series of wars were fought by supporters of this new movement to unseat their animist Soninke rulers. In Fuuta Djalon, the power of the Almamis at Timbo grew stronger.

In the wake of these movements, as modern historians have shown, key historical texts that had shaped the historical consciousness of West African Islamic scholars and griots – oral historians and praise-singers – were reimagined. Some of the foundational histories written in Arabic in the 16th and 17th centuries were recast to justify current political changes, including the Tārīkh al-fattāsh, which centred on the ancient kingdom of Mali, and The Kano Chronicle, which dealt with the rise of the powerful city-state of Kano in northern Nigeria. Meanwhile, oral histories were also recast or invented: in Senegambia, the epic of Kelefa Sane arose to describe the context of the collapse of the Soninke aristocracies.

Processes of historical reinvention tend to accompany moments of great economic and social transformation, such as the one that we’re living through at the moment. They produce a new historical consciousness that has to take account of the transformative experiences that human populations live through. The era of abolition was one such period in West Africa, where the power of old elites collapsed, and new political centres arose. And yet this was also a moment that saw the expansion of poverty and coerced labour, an increase in slavery, and paved the way for the triumph of colonial power at the end of the 19th century.

Thus, in West Africa, the 19th-century abolition era was one of economic crisis, a consequent widespread impoverishment, and also of historical reinvention. It is an important moment to consider as the world enters another such period in the wake of COVID-19.

One of the most common dishes found in the Gambia is called domoda, a rich groundnut sauce mixed with palm oil and served with rice, and often eaten with chicken or fish. Domoda is perhaps the classic Gambian dish, served to special guests or at celebrations. Yet, as with so many ‘traditions’, it is not age-old. The groundnuts (or peanuts) that go into making domoda became ubiquitous across Senegambia only in the 19th century – just as the kenkey (fermented maize or cassava meal) so widespread across Ghana, while cooked in some Atlantic trading posts from the 17th century, became widespread only in the 19th. In fact, when looking for clues as to how experiences of production in the 19th century shaped historical transformations of West Africa, the mealtime is a good place to start.

Groundnuts and maize stand as examples of this history. Originally a Mesoamerican crop, groundnuts were imported on Portuguese ships to Africa in the 16th century, alongside other staple American crops such as cassava and maize. Slave traders were dependent on buying produce from African farmers to feed enslaved Africans on the middle passage, and wanted to ensure their supplies. However, African farmers very rapidly experimented and developed the crop for local markets too. As farmers quickly adapted the crops to West African conditions, on the Gold Coast spectacular new varieties of maize were developed, and two seasonal harvests were reported as early as 1600.

Although production of these crops developed in coastal areas, it took some time for it to be generalised across different parts of West Africa. It was only in the 19th century that the cultivation and consumption of these foods was generalised because it was during this time, while the Industrial Revolution was turbo-boosting the economies of Europe and the Americas alongside the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade, that economic crises affected much of Africa: what emerged at the end was the ‘cash-crop economy’ and the historical relationships of coerced labour whose memories endure to this day.

So what was it about the 19th century that saw these transformations in African production? Far from meaning the end of slavery as Western demand for enslaved persons fell, the 19th century saw slavery’s increase in West Africa as a different type of external demand arose. The abolition of the Atlantic slave trade north of the Equator in the first two decades of the 19th century transformed West African economies. It was one of the major factors in the series of economic crises and political revolutions that shaped West African politics until the advent of formal colonialism in the 1880s, as new classes of entrepreneurial traders arose in areas from the Niger delta to the Ovimbundu highlands of Angola, and older aristocratic ruling lineages decayed.

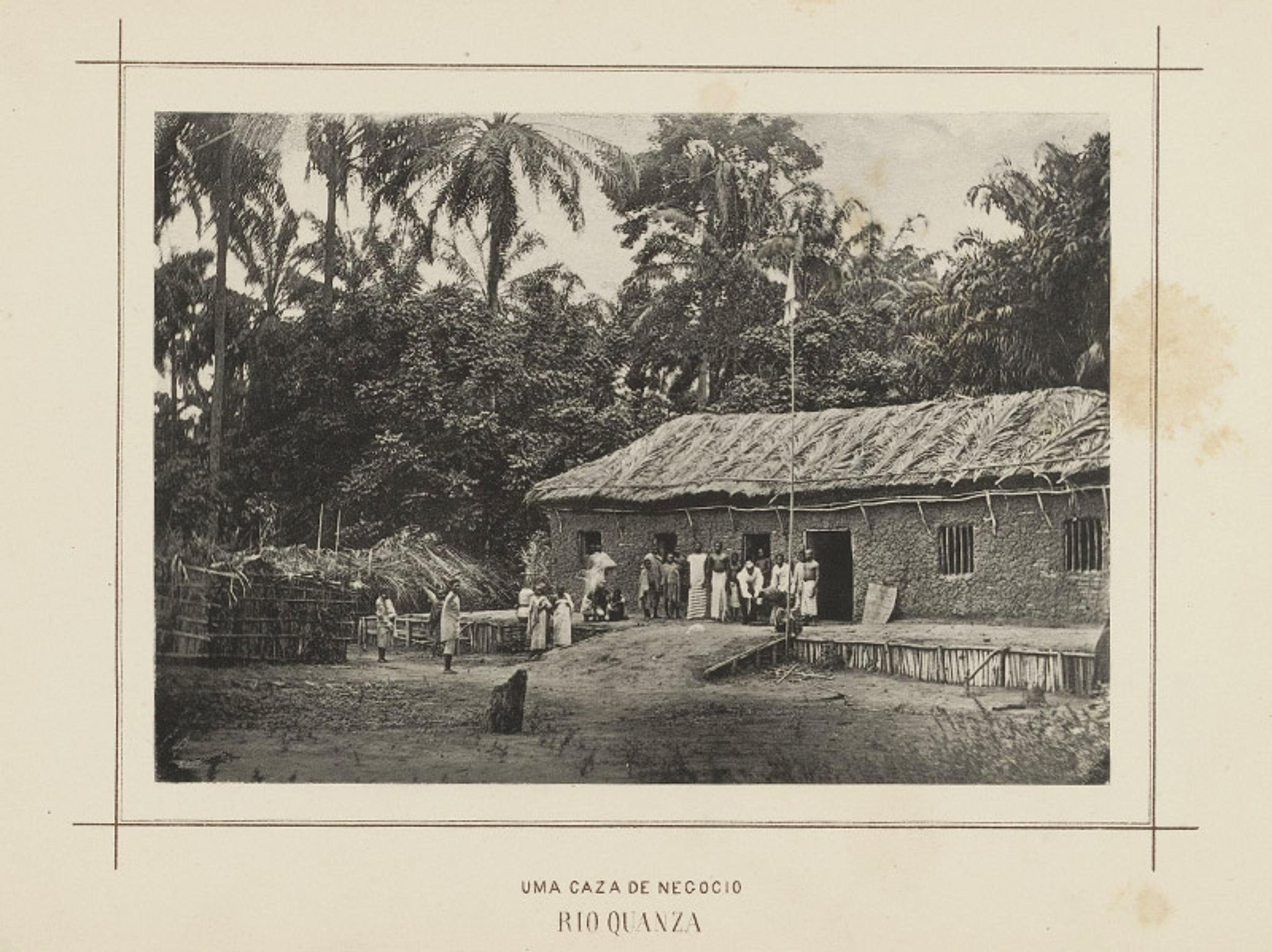

A trading building on the Cuanza River, Angola. Photo from José Augusto da Cunha Moraes’ Africa Occidental (c1876). Courtesy the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The historian A G Hopkins in 1973 called the collapse in demand for enslaved people and the growth of plantation agriculture of crops such as groundnuts and maize in 19th-century Africa ‘the crisis of adaptation’. Hopkins argued that the sudden rupture with the patterns of external supply (of textiles, currencies such as cowries, firearms and alcohol) and demand (for enslaved Africans) wrought an economic crisis for the elites who had cemented their power during the Atlantic slave trade. In the 18th century, these patterns had enabled the development of powerful states across West Africa, from Fuuta Tooro (in the north of modern Senegal) and Fuuta Djalon (Guinea-Conakry) in the west, to Asante (Ghana), Oyo (Nigeria) and Dahomey (Benin) towards the east. However, these states depended on the European demand for slaves for military power: thus, when the transatlantic slave trade collapsed in the early 19th century, so did the economic foundations of their power.

Cadbury’s workers had been sent from Angola along the old slave-trading routes. They worked in conditions little different from the slavery of earlier times

Therefore, in the first decades of the 19th century, this economic crisis became a political one as well. As European traders moved away from their centuries-old demand for enslaved persons, they began to focus on commodities – cash crops. In doing so, they established the parameters of the cash-crop economies that characterise much of the African economic landscape to this day: coffee began to be grown in Angola for export, cotton in Mozambique, and the trend continued.

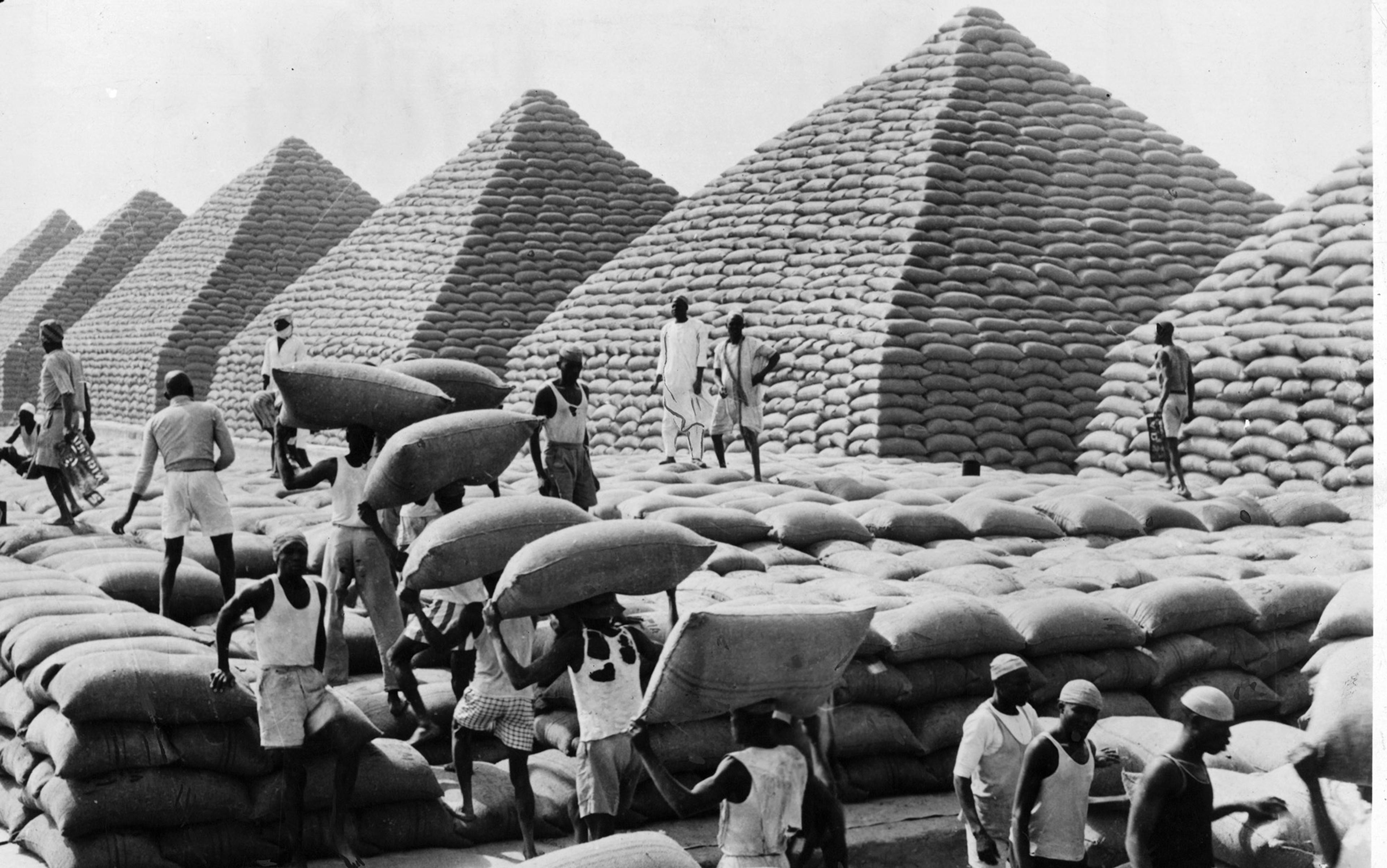

The expansion of cash cropping was deeply connected to the large increase in slavery on the continent during the 19th century, as production of the groundnuts and maize that today give us domoda and kenkey increased, alongside that of crops such as cotton and palm oil. This growth in plantations required a large increase in organised labour; following the patterns set in New World plantations, this labour demand was often met through expanding the use of slavery, shaping the sort of labour relations we’ve seen in the Fuuta Djalon. This eventually came to public attention in the first years of the 20th century when the Cadbury company found itself in a scandal. Cadbury sourced more than half of its cocoa from the islands of São Tomé and Príncipe in the Gulf of Guinea, where the labour was still being provided by ‘contract labourers’. These workers had been sent by Portuguese agents from Angola along the old slave-trading routes. They worked in conditions little different from the slavery of earlier times. In 1908, Cadbury withdrew its share of the São Tomé and Príncipe market and looked instead to the Gold Coast, developing the cocoa interests that mean that Ghana is still one of the world’s largest cocoa producers.

The impact of the economic crisis in Africa that followed the abolition movement has thus lasted to this day. It was the abolition of slavery that pushed African economies to reorient themselves towards cash-crop production. This change was intensified in the colonial era, entrenching African reliance on external markets and demand, and hence their vulnerability to the sort of economic shocks that are buffeting the world in 2021. However, while the shift to cash cropping intensified practices of forced labour in Africa, it also brought the rise of a new entrepreneurial class of African traders and merchants. This new class came to dominate urban life in much of coastal West Africa by the end of the 19th century: thus, some historians have critiqued Hopkins’s notion of a ‘crisis of adaptation’, for certainly – and as in any crisis – what was a crisis for some was an opportunity for others.

In his study of Igbo traders and political change in the 19th century, the Nigerian historian Kenneth O Dike in 1956 revealed that one of the consequences of the shift to cash crops was the opening up of the economy to small- and middle-income traders. The slave trade had been controlled by large states producing human captives through warfare, and therefore was usually dominated by their warrior aristocracies. However, the palm oil trade that dominated here didn’t require large sums of capital for initial investment, and thus a class of small-scale entrepreneurs grew up in Igbo areas whose commercial savvy and knowhow has remained famous in Nigeria to this day.

Further south, in the highlands of central Angola, similar conditions favouring the rise of an entrepreneurial class transpired. As the historian Jill Dias has shown, the rise of the commodity trade favoured small- and middle-income traders whose ability to move products around the mountainous regions of central Angola and down to the coast gave them an advantage. Entrepreneurialism characterised trade here, as it did in south-eastern Nigeria and many other parts of Africa at the same time.

In the end, abolition upended existing relationships of trade and power, as economic crises tend to do. As with all revolutions, there were winners and losers – probably more of the latter than the former. Those able to take advantage of the new commercial winds formed an entrepreneurial class who soon developed the new printing and publishing industries, booming in Accra and Lagos and other cities as the colonial era took shape. For many others, though, the impact was an increase in coerced labour, forced relocation and eventual political disempowerment as colonialism took over from the fractured political elites that the crisis had left in power.

You don’t have to dig too hard beneath the surface to locate the memories of these 19th-century economic crises and their consequences. They emerge in family histories in many parts of West Africa that often begin with a tale of migration (or dislocation); and in the meals of domoda and the like that are cooked at great celebrations, concealing their own histories of movement, production and change. As great celebrations come to seem like a distant memory during our own year in which the relationships of trade and power have been upended, thinking about them and the stories that they tell is a reminder of the complexity of this resonant history of crisis.

A good window onto how these systems of cash-crop production worked can be seen in the Gambia. The country is named after the river, but most rural communities live along the bolons, or tributary creeks that pour into it (and which themselves can easily be 50 or 100 metres wide). It’s along these bolons, and the further smaller creeks that feed into them, that you will find the ruins of peeling whitewashed buildings standing by small jetties. These were the loading stations for the groundnut crops that were brought by donkey cart down to the jetty to unload – from here into the cargo boats that took them to the warehouses in the capital, Banjul, and then from there across the ocean.

When I asked about the labour force, Omar’s face clouded over, and he looked sad

In colonial times, while there were production quotas that villages had to meet, the organisation was left to local initiative. The alkalus (headmen) controlled the distribution of land, and much of the farming was done by stranger-farmers, young men who often came from afar: they would be leased land in return for a share of the produce, hoping to save enough money to put down the brideprice, or dowry (which is paid by the groom and not the bride in West Africa, as opposed to the Western tradition). Thus, movement and its relationship with the norms of social life were enshrined in production long into the colonial era, even when the aftershocks of the 19th-century economic crises had rippled away.

In the first decades of the 21st century, cashew and mango plantations have grown, offering smaller farmers the chance to make better profits than the traditional groundnut crop. Before the COVID-19 crisis, mangos could be boxed up on a farm and put on a supermarket shelf in Paris or Madrid within four or five days. On one visit to Casamance in Senegal a few years ago, a friend took me to his mango farm. It was a stultifying day at the end of the dry season, and the mango trees offer another beautiful gift – their shade. When the hottest part of the day had passed, Omar boxed up a selection of the ripest fruit, insisting that I take them home to eat with my family. But this wasn’t really the tradition, he added, he had only recently converted the family lands from groundnuts and planted this orchard of mangos.

I asked him then, as we walked back through the village, how long his family had been in the groundnut business, and then Omar told me some of the family history: how they had been from the northern part of Senegal and moved south in the 19th century to help manage the new groundnut plantations. We were quite an influential family! he boasted. Everyone knew who we were.

As we waited for a bus to take us back to the nearby town, we met an old man who started to talk about history. Oh yes, Omar’s family was famous. There were some who were traders, and others who were warriors. People had to fight to survive in those decades, and life was not easy. It was very hard to save enough money to marry, to pay the brideprice.

Then the historian’s curiosity got the better of me, and I asked about the labour force. Omar’s face clouded over, and he looked sad. That was what people in the West did not understand, he said, because they had never experienced real poverty. Once you knew what that was like, you would never choose it. Because in those days, once the crisis had set in, it had been easy to get people to work on those plantations: when you have nothing, he said, when there is an economic crisis, the powerful are even more in command than ever, because you will do anything they say just so that you have enough to eat.