We live in a world where less and less seems to be universally agreed on, but there is one important exception. Virtually all national governments, either implicitly or explicitly, agree that respect for the ‘sovereignty and territorial integrity’ of other nation-states is a fundamental principle of the international community. According to the United Nations Charter ratified in 1945, states are committed to refraining ‘from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.’ (Note that in this essay I use the term ‘state’ rather than the more ambiguous terms ‘nation’ or ‘country’. This does not refer to subordinate political units such as individual states within the United States). It is rare to find anyone who will openly support the idea that annexing territory from another state, after forcibly conquering it, could be legitimate. Conquest exists, of course, but it is almost always disguised as something else, whether it is Russia’s technique of promoting the secession of neighbouring regions, and then annexing them after holding a referendum, or Israel’s technique of calling it an occupation rather than a conquest.

Political leaders today take pride in rejecting conquest as illegitimate, which makes our current international order seem civilised and peace-loving. What could possibly justify taking by force territory that is not one’s own? But the idea that conquest is never legitimate and acceptable in international affairs is relatively new. As the 17th-century Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius argued, treaties that end wars should be honoured, even if they forcibly impose unjust conditions, for example by taking away part of a state’s territory. Such treaties, even if unjust, may sometimes be the only way to end wars, and rejecting them on principle would merely make it impossible for wars to end. Moreover, as the 19th-century American jurist Henry Wheaton observed: ‘The title of almost all the nations of Europe to the territory now possessed by them … was originally derived from conquest, which has been subsequently confirmed by long possession.’ The very existence of almost any state, from this perspective, seems to depend, inevitably, on the legitimacy of conquest.

But instead of Grotius’s law of nations, which attempts to limit conquest by allowing it a regulated path to legality, we have an international order that guarantees as an absolute right the territory of each state as it currently exists. What is banned is not profiting from conquest as such, but only profiting from conquest that took place after about 1945, or even more recently in the case of conquests against colonial empires by emerging independent states. Apparently, the conquests that happened before a certain point in history are completely legitimate, but now conquest is one of the worst crimes imaginable.

How did we come to have an international order that is so radically protective of the status quo?

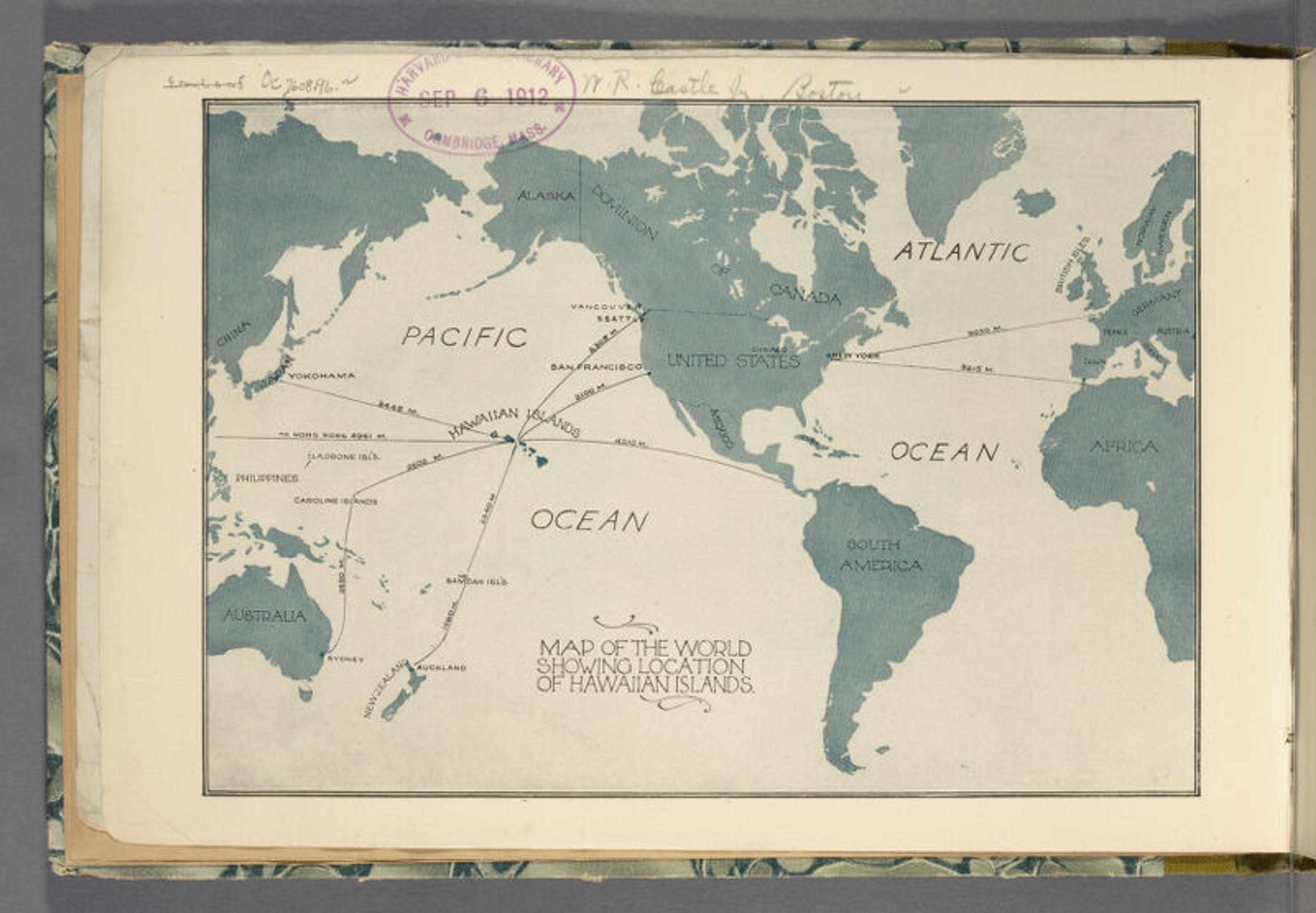

Anything so widespread and deeply entrenched as today’s prohibition against annexation by conquest is a product of many different factors coinciding. One of the most puzzling things about it is that those who seem most capable of conquest on a large scale are some of the biggest opponents of forcible territorial expansion. It is no surprise that conquest is deplored by victims of conquest, such as Palestinians or Ukrainians, or those who could become victims of conquest, such as Estonians or Taiwanese. The interesting question is why, for example, the United States, still by far the world’s largest military force, is a major proponent of the rule against annexation by conquest. The US maintains military force on every continent in the world and uses it frequently, but not since annexing the Northern Mariana Islands, which it conquered during the Second World War, has the US annexed conquered territory. Why would the world’s only superpower tie its own hands in this way?

An LVT Comes Ashore, Saipan (1944) by William F Draper. Courtesy Wikipedia

The answer to this question, in part, derives from the driving forces that made up the US from its beginning: a particular brand of settler colonialism, driven to continental dominance by the thirst for land ownership, plantation slavery, and agricultural and later industrial capitalism. Up to around 1900, the US engaged in relentless territorial conquest. In this respect, it was like many other empires in world history, but one thing that set it apart from other historical empires was the degree to which its conquests were driven by groups of settlers expanding more or less of their own initiative. Before the US became independent, while it was still a part of the British Empire, the British had tried to restrain settler expansion, which had earlier provoked expensive wars that threatened the European state system with instability. When the US achieved independence, the new federal government was less committed to honouring territorial agreements with Indigenous peoples than the British had been. Still, the federal government struggled to regulate the chaotic westward advance of settlers. A perhaps surprising number of states (California, Florida, Hawaii, Texas and Vermont) experienced a short life of independent sovereignty, before joining the US. And those were only the successful ones: plenty of Vermont-like entities sprang up in the Appalachians that never received official recognition, with names like Vandalia, Watauga, Transylvania, Westsylvania, and so on.

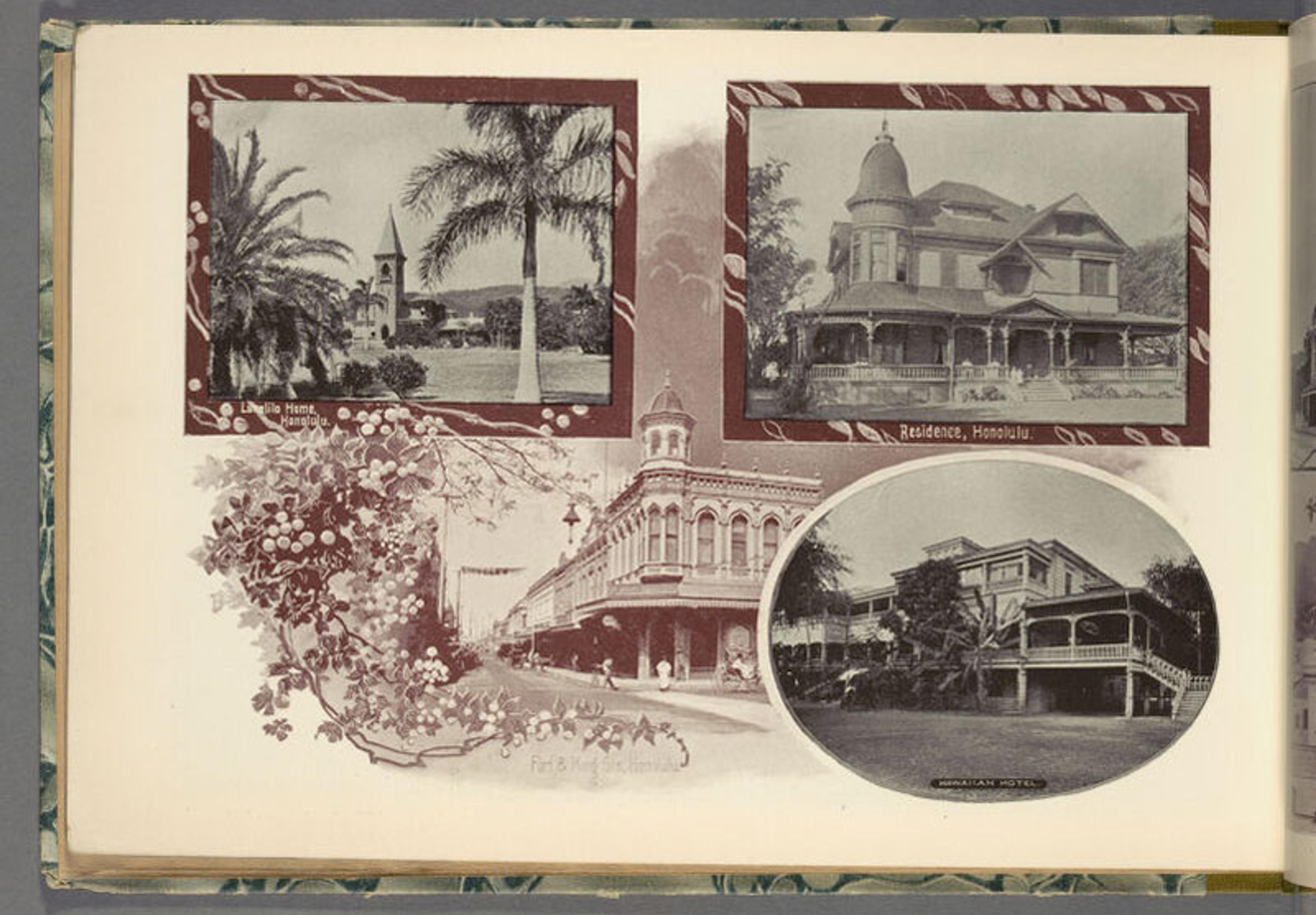

So conquest has always been central to the history of the US, though not in a way that was typical of European colonial empires, in rebellion against which it had been created. Although the US federal government enabled and encouraged settlement, the real engine of expansion was the apparently inevitable westward march of settlers. But was this type of conquest really so fundamentally different from the European imperial practice that the US had declared, in the Monroe Doctrine, to be at an end in the Western Hemisphere? By the 1890s, settler expansion had reached Hawaii, and the creation of a European-style overseas empire began to seem a real possibility for the US. The nature of US empire became a major topic of public discussion.

Conquest in the 1890s was caught between laissez-faire economics and liberal egalitarianism

Americans at the turn of the 20th century debated how to conduct their empire, and many historians have portrayed the disagreement as between ‘imperialists’ such as naval officer and historian A T Mahan and ‘anti-imperialists’ such as conservative sociologist William Graham Sumner. But the ‘imperialists’ and ‘anti-imperialists’ had much in common. For both Mahan and Sumner, the conquests of imperial Spain were anathema, being contrary to the kind of liberty and enterprise that drives the life of nations. For Sumner, the US conquest of the Philippines was tantamount to ‘the conquest of the United States by Spain’, as colonial expansionism would now infect US policies. For Mahan, too, known for his campaign to build a strong navy and expand into Hawaii and the Panama Canal, Spain was a symbol of imperialism of the wrong sort. Spain sought wealth from its colonies ‘by digging gold out of the ground’, shipping it back to Spain, and buying goods made by other countries. But unlike the state-directed, top-down imperialism of Spain, Mahan thought that ‘colonies grow best when they grow of themselves, naturally,’ out of the character and ambition of their settlers. Mahan’s views reflected the distinctive settler-driven expansion of the US up to 1900.

Once US settlement spanned the breadth of North America, there was no obvious next step. Conquest in the 1890s, as Sumner saw it, was caught between laissez-faire economics and liberal egalitarianism. If the conquered were a ‘civilised’ people, there was no point in conquest, as the benefits could be gained through a trade agreement. If they were ‘uncivilised’, extending rule over them would strain the doctrine that ‘all men are equal.’

The US resolved this tension with a distinctive mode of imperialism, evolving from a settlement-driven one to one in which trade and business, in theory, formed the vanguard. This new type of US imperial expansion built on the old, in the sense that it was not explicitly managed by a centralised state or imperial metropole. Instead, the yeoman farmers and homesteaders of 19th-century expansion were replaced, for the 20th century, by export manufacturers and railroad developers. Their economic activities abroad, US leaders maintained, would bring prosperity home and relieve class conflict.

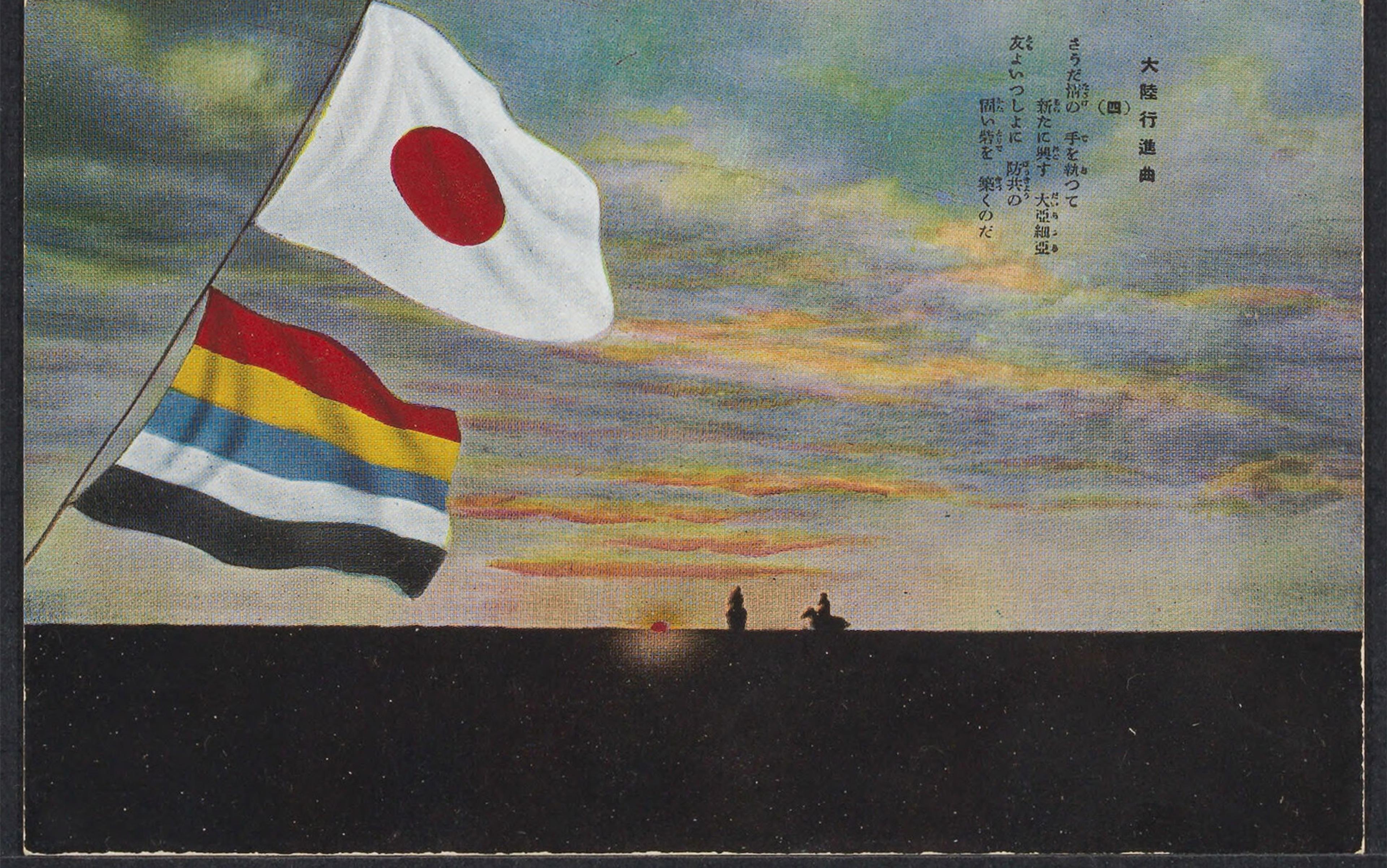

The proponents of the Open Door policy (United States, Great Britain and Japan) pitted against those opposed to it (Russia, Germany and France); cartoon from 1898. Courtesy the Library of Congress

The blueprint for this new type of imperialism was contained in the ‘Open Door notes’ of 1899 and 1900. The US ‘Open Door’ brief was a diplomatic offensive against old-fashioned European imperialism in China, designed to clear the way for US enterprise there. The 1899 note, a circular telegram that the US secretary of state John Hay sent to the capitals of all the great powers, affirmed the right of all nations to trade on equal terms in China. Hay sent a second note, in 1900 at the height of the Boxer Rebellion. It gave a brief interpretation of the disorder and violence involved in that rebellion and stated that, in response, US policy would be to pursue peace in China, ‘preserve Chinese territorial and administrative entity’, protect US legal rights in China, and ‘safeguard for the world the principle of equal and impartial trade with all parts of the Chinese Empire.’

This US maintained and supported the Open Door policy in China throughout the early 20th century. In 1915, the US secretary of state William Jennings Bryan issued another note, stating that the US would not recognise any agreement ‘impairing the treaty rights of the United States and its citizens in China, the political or territorial integrity of the Republic of China, or the international policy relative to China commonly known as the open door policy.’ After the First World War, the Open Door policy was the basis of the Nine-Power Treaty of 1922, in which the US, the UK, Belgium, China, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands and Portugal upheld the policy, agreeing to ‘respect the sovereignty, the independence, and the territorial and administrative integrity of China.’

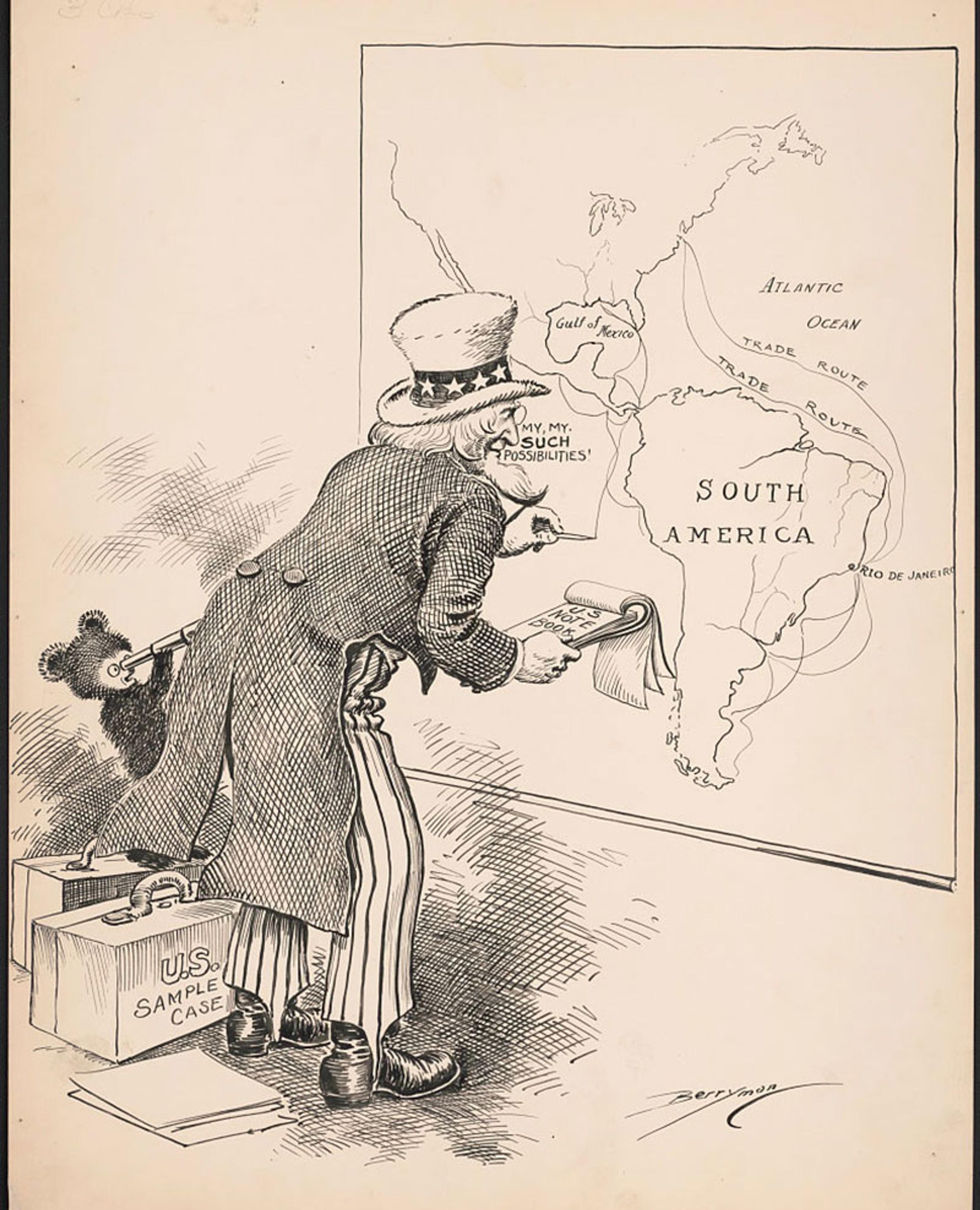

My, My, Such Possibilities (c1913) by Clifford Kennedy Berryman. Courtesy the Library of Congress

Theodore Roosevelt inspecting a steam shovel excavating the Panama Canal in 1906. Courtesy the Houghton Library, Harvard University

Almost immediately after the Spanish-American War of 1898, in which the US conquered the Philippines, Puerto Rico and Guam, US officials began advertising US opposition to conquest. The Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, stating the US right to intervene anywhere in the Western Hemisphere to uphold law and order, was accompanied with the notion that ‘It is not true that the United States feels any land hunger … All that this country desires is to see the neighboring countries stable, orderly, and prosperous.’ In 1906, the US secretary of state Elihu Root embarked on a tour of South America, repeating language such as: ‘We wish for no victories but those of peace; for no territory except our own; for no sovereignty except the sovereignty over ourselves.’ It was at this point that the US interventions in Latin America accelerated considerably. During Theodore Roosevelt’s administration (1901-09), the US took over the Panama Canal (1903), occupied Cuba (1906-09), and intervened in the Dominican Republic (1904) and Honduras (1903 and 1907). But after more than a century of territorial expansion by both purchase and conquest, from European empires, Indigenous peoples and settler republics, the US renounced territorial conquest.

US Troops surround the palace in Havana, c1898; photograph by S A Cohner. Courtesy the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard University

The idea of abolishing conquest is not always associated with the US and its informal imperial aspirations. In recent years, analysts at prominent international affairs think-tanks have come to associate the principle of territorial integrity with what they call the ‘rules-based international order’. This they typically trace to the founding moment of the UN in the wake of the Second World War, where the international community applied the lessons of the war to create a new, more peaceful international order. Many scholars point to the League of Nations Covenant, signed in 1919, as the beginning of the abolition of conquest, similarly arguing that a general desire of Western nations to prevent future wars was the main motivation. In Article 10 of that document, the League promised to ‘respect and preserve as against external aggression the territorial integrity and existing political independence of all Members of the League.’ So what role did the Open Door policy play in the abolition of conquest worldwide?

In order to understand this, we first have to understand why Article 10 was, from the start, controversial and ambiguous. In the US, Article 10 was the main reason the Senate rejected League membership, in that it seemed to open the possibility that it would require the US to intervene in foreign wars. Canada tried several times to strike out or modify the article. Why should the Canadian military be held responsible for propping up potentially all the territorial boundaries in the world, some of which might be unjust, and which some people might be rightly struggling to change?

In January 1923, France invaded and occupied the Ruhr region of Germany in response to non-payment of indemnities for the First World War. In August that same year, Italy invaded and occupied the Greek island of Corfu after an Italian general was murdered in Greece, and Italy did not receive the satisfaction it desired. France worried that the wrong kind of League involvement in the Italy-Greece affair could lead to uncomfortable scrutiny of its occupation of the Ruhr. What would Article 10 mean in these situations?

The League of Nations’ Permanent Advisory Commission no doubt had these issues in mind when during the same year they tried and failed to come to an agreement on a treaty that might give further concreteness and specificity to the League Covenant, by defining ‘aggression’. The delegates of France, along with those of Belgium, Brazil and Sweden, argued that the old way of thinking of aggression as the crossing of a frontier had lost its value in the conditions of modern warfare, and attempted a more complex understanding of aggression based on a variety of factors. This sophisticated arrangement would have, of course, protected France from being automatically incriminated for its Ruhr occupation. Meanwhile Britain, worried about its ailing global military presence being dragged into a conflict with the US, put an end to the League’s entire effort to define aggression, with the UK prime minister Ramsay MacDonald’s memorable argument that any definition of aggression would serve only as a ‘trap for the innocent and a signpost for the guilty’. In other words, cynical lawyers would use it to punish the wrong states, while aggressive states would find ways to circumvent it. At the end of the 1920s, it was anything but clear what Article 10 meant.

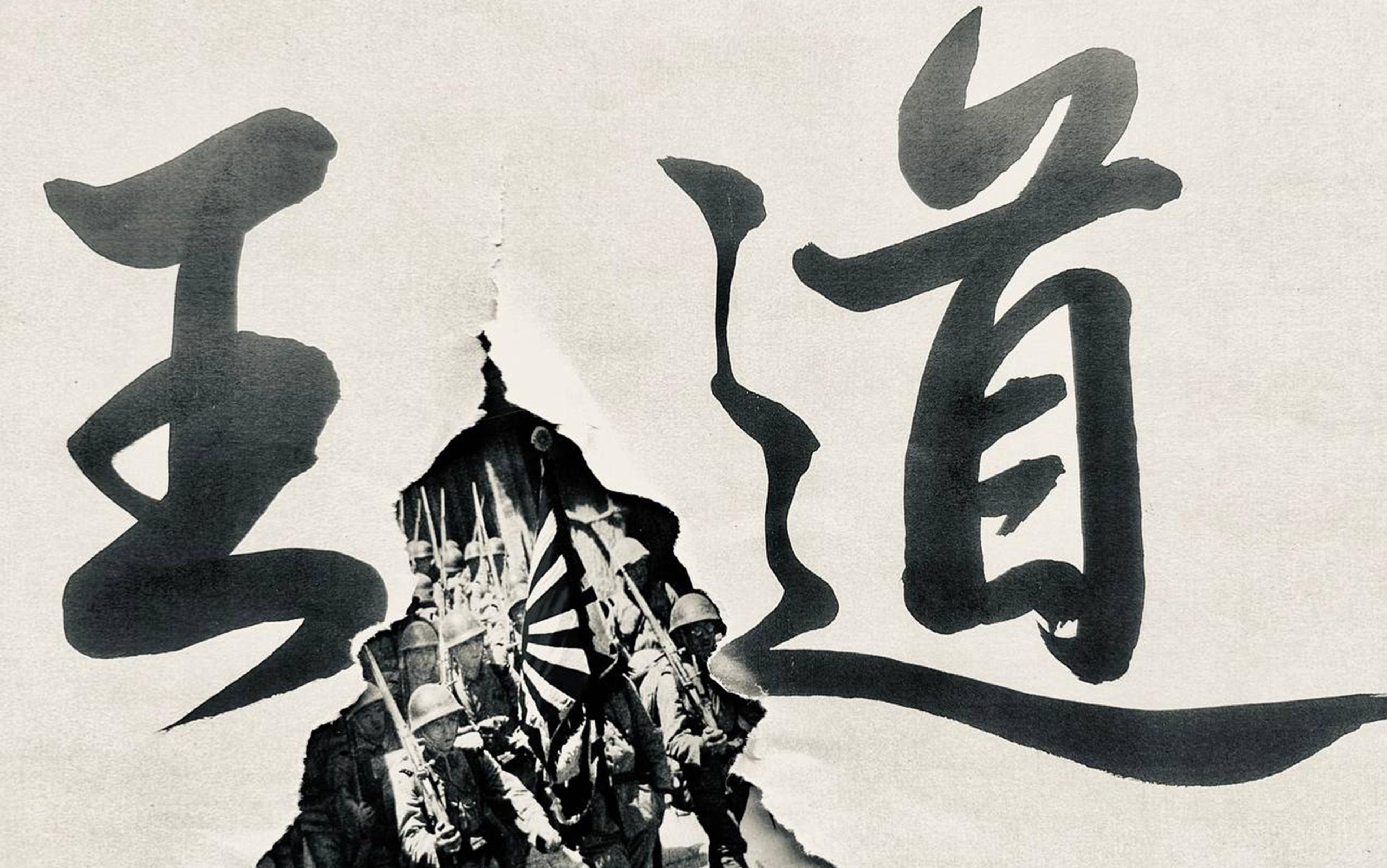

Japan was not simply protecting its ownership of the railway. It was taking over political control of Manchuria

By the 1930s, the League had moved from confusion to a general panic about the state of affairs in the world. The Wall Street crash of 1929 spread economic depression globally, Britain went off the gold standard, Japan conquered Manchuria, establishing its puppet state of Manchukuo there, and by 1933 Hitler was in power in Germany. World conditions were now compelling the League to give greater clarity to its mission.

Enter the US secretary of state Henry Stimson, a product of Harvard Law School, member of the influential Skull and Bones secret society while an undergraduate at Yale, and husband of the great-great-granddaughter of Roger Sherman, one of the US Founding Fathers. Stimson, like many others, followed the Japanese military action in Manchuria closely with an eye towards maintaining the Open Door. The prevailing view in Washington on these developments was initially similar to the British view: both Japan and China had good arguments in their favour, and little could be done anyway, so the Open Door could best be preserved by a negotiated agreement among the main interested parties. Stimson’s perceptions, in retrospect, were more farsighted, prompting him to break ranks and consider that Japan had now exited the realm of responsible great powers that could be negotiated with. Japan was not simply protecting its already established ownership over the South Manchuria Railway, as it claimed. It was taking over political control of the whole of Manchuria, and bombing parts of the city of Jinzhou far away from the railroad zone.

But Stimson was unable to find support for his preferred strategy of threatening Japan into backing down. His most consequential move was to send a diplomatic note essentially reiterating Bryan’s position, denying recognition to any agreement or situation arrived at in violation of US treaty rights, ‘including those which relate to … the territorial and administrative integrity of the Republic of China, or to the international policy relative to China, commonly known as the Open Door Policy.’ Unlike Bryan’s note, however, Stimson’s became the Stimson Doctrine, or the doctrine of non-recognition of conquered territory. Through actions by the League of Nations Council and Assembly, the 1933 Anti-War Treaty of Non-Aggression and Conciliation, and through more recent agreements, the non-recognition of conquest became international law, and it remains so. This is why, for example, most governments do not recognise Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.

How did Stimson’s denial of recognition to conquered territory in China become general international law in 1932, whereas Bryan’s essentially similar note was largely ignored in 1915? One thing that helped the European powers begin to see things from Stimson’s perspective was that, after he sent his note, the Japanese attacks on China did not remain in Manchuria but spread to Shanghai, where the major colonial powers had stationed significant personnel and property. But another part of the reason was that in 1915 the US was a peripheral power, sitting on the sidelines of the Great War. By the end of that decade, that same war had made it a European power and devastated its rivals. The British had never been fond of this type of diplomacy; they thought it too moralistic and that it played risky games with innovations in international law. Sir John Pratt, in the Foreign Office, considered that ‘Non-recognition was a peculiarly American technique, the fruit of American isolationism, and it was wholly out of harmony with the British tradition in international affairs.’ But by the early 1930s, Britain was presiding over a decaying empire that was vulnerable to threats such as the Japanese, altering its position considerably.

Sir John Simon, the UK foreign secretary, hoped to avoid disaster primarily by keeping everyone pleased: the US, the League and Japan, all at the same time. So when Stimson tried to get the parties to the Nine-Power Treaty to reaffirm together the principles of the Open Door policy, in a diplomatic offensive against Japan, Simon found a way to square the circle. Rather than choosing between the US, Japan and the League, he would hide behind the League as a mouthpiece to proclaim Stimson’s doctrine of non-recognition, and thus avoid stronger actions such as economic sanctions. With the League Council already issuing a rather mild statement to Japan, Simon was able to arrange for a paragraph stating the Stimson Doctrine to be inserted, and the statement was approved on 16 February 1932. Stimson was happy that his doctrine was endorsed by the League Council. The League Council, in general, was very happy to accept the non-recognition paragraph, which appeared to make the whole thing principled and sound. And Japan could not complain because it had avoided any sanctions or explicit condemnation that Stimson might have sought.

Meanwhile, the new doctrine of non-recognition, much celebrated by lawyers, made little difference in Manchuria. As it turned out, the occupation of Manchuria was only a prelude to the Second World War, the largest war of conquest ever seen. In the following years, it did little to deter Italy from conquering Ethiopia with almost unparalleled brutality, or Japan from invading the rest of China and perpetrating the infamous Massacre of Nanjing.

Why does it matter that today’s prohibition of conquest is, to a large extent, a product of US informal imperialism? One reason it might matter is suggested by the apparent change in direction of US foreign policy signalled by Donald Trump’s election to the presidency in 2016 and in 2024. In 2019, under Trump, the US became the first country to recognise Israel’s de facto annexation of the Golan Heights, conquered from Syria in 1967. And soon after Trump was elected the second time, Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelenskyy changed his position on giving up territory to Russia, indicating territory could be ‘temporarily’ ceded in exchange for NATO membership. Could the US stance against annexation-by-conquest be softening and, if so, what would be the consequences for global order?

Trump’s rhetoric does matter and, if it is matched by more actions akin to the 2019 recognition of the Golan Heights, it could significantly compromise the extent to which it is perceived that conquest won’t be recognised as legitimate. But the way that such a shift in US policy would matter also depends on a great deal else, particularly the actions of other states. US Open Door imperialism was not pursued in a vacuum; in each case, it depended on elites in other nation-states perceiving US promises not to engage in conquest as signifying benign intentions.

After Root’s 1906 tour to South America, he and other US officials were able to spark interest in an American Institute for International Law, which would define the particular international law of the Western Hemisphere. Some Latin American jurists hoped that, through legal collaborations with the US, they could persuade it to limit or end the frequent US-sponsored coups, interventions and occupations that plagued the region. And when the 1932 League of Nations Council declaration making the Stimson Doctrine international policy was followed by a similar League of Nations Assembly, this time it was driven by clamour from smaller nation-states, including European and Latin American ones, to use the moment of Japan’s conquest of Manchuria to take a stand against conquest in general. Even if Czechoslovakia had little to fear directly from Japanese imperialism, a strong League seemed the best protection from Germany’s impending bid to redraw the map of Europe by force. So the prohibition of conquest depends both on Great Power visions of world order and the narrower interests of the majority of states in not being invaded, something that is unlikely to change even if the US were to abdicate its position as leader of the free world.

Ask any international lawyer: the term ‘territorial integrity’ is complex

The US sponsorship of the principle of non-conquest, and its uncertain future, matters because the principle of non-conquest has been crucially shaped by the US preference for informal rather than formal imperialism. Ask any international lawyer: the term ‘territorial integrity’ is complex. It involves both non-conquest, and also prohibits almost any kind of interference in the sovereignty of another state. But the US president Woodrow Wilson, in promoting the League of Nations, had a different definition in mind, one that supported, rather than prohibited, US imperialism. Testifying before the Senate, he stated that a nation’s ‘territorial integrity is not destroyed by armed intervention; it is destroyed by the retention of territory, by taking territory away from it.’ On this interpretation, it is nothing other than annexation-by-conquest that is ruled out by the territorial integrity principle. Only by defining territorial integrity so selectively could Wilson make sense as a supporter of it as a general principle while at the same time continuing the US policy of treating armed intervention in Latin American affairs as a crucial tool of governance.

This narrow interpretation of conquest has been revived many times since, but perhaps most importantly during the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the US and its coalition partners. In the lead-up to the invasion and its aftermath, the US president George W Bush and the UK prime minister Tony Blair emphasised their respect for Iraq’s territorial integrity, meaning not that they wouldn’t use conquest to gain control over the country – this they did with a spectacular show of force – but that they would not alter its borders. Upholding the sanctity of territorial integrity and interstate borders, they hoped, would signal a regard for international order that would make up for their refusal to act multilaterally and through consultation with the UN Security Council in invading Iraq.

The narrow interpretation of territorial integrity strictly as a rule against annexation of conquered territory is the one that stands to lose the most from recent annexations by Russia and Israel. It is not that every contested border around the world will suddenly be up for grabs, with military aggression breaking out in every corner of the globe. Almost all states frequently repeat support for the principle of territorial integrity in response to events where it appears threatened. Even if Iran and China did not participate in the UN General Assembly vote to condemn Russia for its invasion, they still affirmed the territorial integrity of all the relevant states. While the US may have been at the forefront of the abolition of conquest, there are too many other states in the world that are keen to protect their own borders for territorial integrity to be simply forgotten. But according to the analyst Bonny Lin writing in Foreign Affairs in 2023: ‘Some Chinese scholars have suggested that sovereignty and territorial integrity should be viewed as only one of 12 core principles for China to balance – in other words, not the most important one, or a value that needs to be respected completely.’ Annexation-by-conquest may remain illegal but may also decline in its perceived gravity, relative to other kinds of violations of a country’s territory.

International orders come and go. Before the territorial integrity principle, there was a different system, in European states and their colonies, in which conquest was regulated by norms and principles but not explicitly illegal. And change will come again to the international order. Shifts in relative power between different social and political forces in the world, with different cultural and moral practices, make this all but inevitable. What comes next is impossible to predict with certainty, but it is becoming less and less likely that attitudes towards conquest will be shaped by the ideological constructs of the US.