Perhaps 40 of us, an equal number of men and women, sat on rows of folding metal chairs in a high-ceilinged room in the ground floor of a church in New York’s East Village that had been converted into a community centre. Most were 30-something, good-looking, well-dressed Manhattan professionals. Nicole Daedone, author of the book Slow Sex: The Art and Craft of the Female Orgasm (2011), and inventor of a sexual technique called ‘Orgasmic Meditation’, walked confidently to the front of the room. She was a tall, attractive, rail-thin woman, with high cheekbones and shoulder-length blonde hair. She wore a black skirt and top that looked sprayed on, and black suede boots with four-inch stiletto heels.

Although this was the first time I was seeing her, I’d been on the track of Daedone and her ilk for some weeks as a journalist. They were part of what Daedone like to call the ‘Slow Sex’ movement, but which I was starting to see as a full-blown orgasm industry, composed of groups and individuals mostly centred in the San Francisco Bay area. All focused on the skill of gently stimulating a woman (or a man) to the edge of climax in order to extend his or her orgasms, and therefore theoretically her ecstasy, past its normal limits. They were connected in that they spoke the same lingo, had identical or similar practices, and appeared to share the same Ur-source. What that source was I wasn’t sure yet, but I was getting close.

By her own admission, Daedone has led something of a chameleon’s life. ‘I have been a magna cum laude academic, a gallery-owner, a stripper, an underworld traveller, and the daughter of a man who died in prison for child molestation,’ she wrote in a blog recently. ‘I have been a postmodern feminist lesbian and a meditation practitioner, a yogini and a mystery-school student.’

She must also have been involved in psychotherapy. In a 2011 TedX talk, Daedone explained how she came to the revelation that something new was needed. ‘Woman after woman was coming through my office,’ she said, ‘chanting what I call the Western Woman’s Mantra: “I work too hard, I eat too much, I diet too much, I drink too much, I shop too much, I give too much, and still there’s this sense of hunger that I can’t touch.”’ I could hear low murmurs of agreement from some of the women in the audience.

‘We have a pleasure deficit disorder in this country,’ she continued. ‘I don’t think it’s medical. I do think it’s a cultural issue. And I do think there is a cure. That cure is orgasm. But it’s going to be a very different definition of orgasm than we know. It’s going to be a definition of orgasm that actually works with a woman’s body.’

As she talked, Daedone made a curling gesture with her right-hand index finger, a finger that knows how to play a woman like a cello. She isn’t currently a lesbian, as her concupiscent personal dating blog makes clear, but she was about to perform on her close friend and lieutenant, Rachel Cherwitz, who was hovering nearby, a pale and thin young woman whose sad eyes were framed by dark, shoulder-length brown hair, calling to mind a melancholy angel in a Pre-Raphaelite painting.

‘In a moment,’ Daedone announced, ‘I will put my finger on the upper left-hand quadrant of Cherwitz’s clitoris; if she were facing you, that’s the one-o’clock position. Both she and I will be putting our attention on the same point. It’s a fairly intense point, mind you. And then, just like a master chess player absorbed in a game, or a meditator absorbed in his breathing, you’ll see her get absorbed into that place. The difference is that she will be there with a partner. She will be allowed to have this most profound and deep experience with another human being.’

Her followers don’t call her ‘the Jimi Hendrix of strokers’ for nothing

We in the audience made awkward small talk as Daedone’s assistants set up a padded massage table strewn with upholstered pillows. Quietly averting her eyes, Cherwitz stripped off her trousers, and then her underpants. She climbed up on the table to sit facing us, and then gracefully swooned back until her head touched the bolsters, allowing her pale thighs to butterfly open with her knees bent, so that her feet almost touched. One does not often see such an unashamed public display of intimate nakedness in New York City. At Daedone’s invitation, the more adventurous of us crowded in a little closer, and as Cherwitz shifted her hips to get comfortable, the collective pulse quickened. Daedone hooked some lubricant into the crook of her finger and put a gob on her forearm. The lubricant she uses is a specially concocted slippery blend of olive oil, beeswax, shea butter and grapeseed oil.

Leaning over, she placed her left thumb on the lower entrance to Cherwitz’s vagina (the introitus), and then gingerly slid her right thumb and forefinger on either side of Cherwitz’s clitoris. Cherwitz shifted and groaned at Daedone’s touch; her toes began to twitch, and I noticed a small blue tattoo on her ankle.

‘Ooo!’ Daedone exclaimed, looking up at us with an elated grin. ‘She’s already quivering!’

Working slowly and gently at first, she began to stroke up and down and around Cherwitz’s clitoris, ‘lightly as an eyelash’, she said. Cherwitz’s moans grew louder with each stroke, and soon the young woman’s ahs and ums and ohs began to modulate back and forth from an original deep, mournful treble to a high alto trill. After a few minutes, Daedone slowed her stroking and temporarily brought Cherwitz down to earth.

‘I’m grounding her now, do you see? I will take Rachel to several peaks before bringing her back down to a normal level.’ As Daedone picked up her pace again, she invited several of the women attendees to place their hands upon Cherwitz’s thighs to feel her muscles begin to quiver in continuous orgasm.

In orgasmic meditation, or OM (pronounced so that it rhymes with ‘home’), the stroker’s skill lies in slowly bringing his (or her) partner to the very brink of orgasm and then keeping her there, continuously surfing on the crest of ecstasy, for minutes, even hours, without allowing her to fall off into climax. Regular OMing is supposed to have all kinds of positive effects, from increasing energy levels and reducing stress, to restoring hormonal balance, lifting depression, increasing libido, creating a deep connection with one’s partner, and even curing frigidity. Plus, it makes one feel very, very good, obviously.

However, Daedone let us know that what we were seeing was different from the way orgasmic meditation is usually practiced. Normally, the woman will lie on the floor in a special ‘nest’ of pillows and towels and perhaps a yoga mat. She will be naked from the waist down, while her partner, usually a man, but often not her lover, will remain fully clothed. He will sit on a high pillow with his left leg draped over her stomach in a manner that hopefully doesn’t cause uncomfortable pressure. Their right legs will intertwine so that her thighs are pulled apart, allowing him the freest access to her vulva. Before he begins to stroke, the man will take a moment to describe what he sees in simple terms. He might say: ‘I see your clitoris glistening, pink and bright. Your labia are growing darker, almost brown.’ Or he might say: ‘I see a pulse running from the bottom to the top of your vulva.’ Though I could imagine this ritual might lose its gloss if it were carried out every day, Daedone told us that the first time a man paid such close attention to her genitals, her eyes flooded with grateful tears.

Daedone began stroking Cherwitz with greater speed now, pushing her again and again to the cliff edge of climax. Prancing back and forth over Cherwitz’s spread legs, she acted out her friend’s ohs and ahs the way a guitarist mouths the sounds produced on a guitar by a wha-wha pedal. At times, she flapped her whole body over Cherwitz’s supine form like an enormous bird of prey, while throwing her full head of blonde hair back to give us a knowing and triumphant leer. Her followers don’t call her ‘the Jimi Hendrix of strokers’ for nothing. Some 10 separate, minute areas of the clitoris can be plucked, rubbed or brushed, she claims, using as many as five or six stroking variations – and she seemed to be hitting all of them.

Eventually, Daedone brought Cherwitz, and us, down to a ringing silence. Then she placed four fingers on the bottom of Cherwitz’s vulva and held them there with strong pressure, finishing the session. It had been a virtuoso performance.

After a short pause, Daedone pulled Cherwitz back up into a sitting position, facing us. She pointed out dark shadows under Cherwitz’s eyes, noting how plumped up and blood-puffed her lips had become in the deep engorgement of sexual excitement. ‘This is what women’s makeup is designed to emulate,’ she said. Cherwitz smiled wanly. She had been skirting orgasm for perhaps 15 minutes without ever climaxing. She seemed only half-emerged from a revelatory dream.

The notion of being able to strum a woman like a musical instrument is, of course a decidedly male fantasy – even a puerile one: witness Holden Caulfield in Catcher in the Rye (1951) saying: ‘a woman’s body is like a violin and all, and that it takes a terrific musician to play it right’. To the women in the audience who saw themselves as casualties of the dating wars, Daedone offered a big sister’s sexual frankness and the promise of regular, deep, exalted connections to men with whom they did not have to have sexual relationships or even know very well. If you practised orgasmic meditation every day, she claimed, you would return to the dating arena with the determination and poise of a sexual ninja, girded and ready for action. (There could be no better ice-breaker on a first date, I imagine, than to ask your potential dinner and movie companion to treat you to a 13-minute orgasm.)

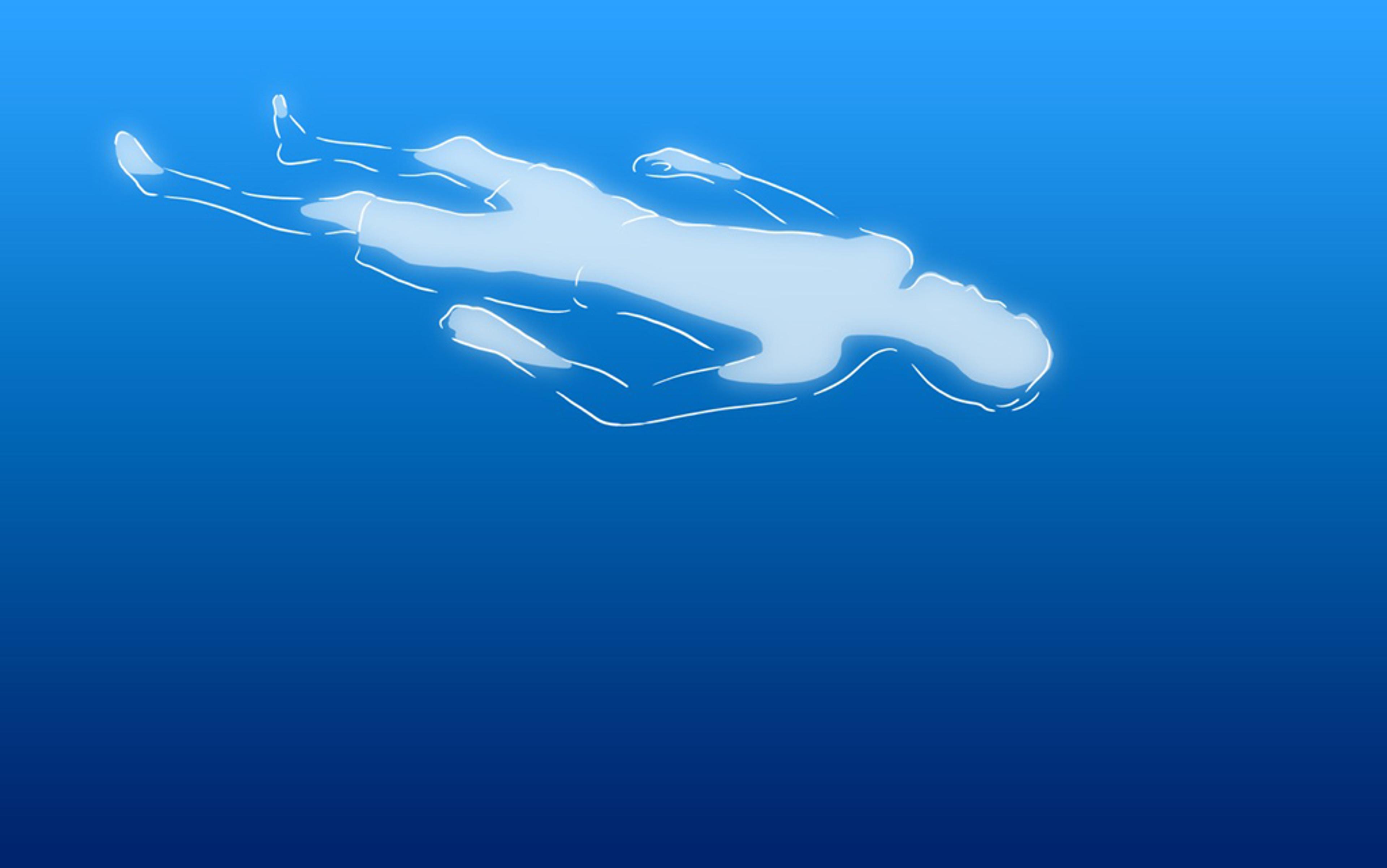

But what of the men? Daedone had little trouble luring young males to her gatherings, for voyeuristic reasons perhaps. But the question she’s often asked is: ‘What’s in it for the guy?’ Daedone maintains that OMing opens up neurological pathways through the tip of a man’s finger, so strong that his pulse and breathing will become locked with those of his partner, and she says that through these pathways the ecstatic high is shared. I’d developed my own unscientific ‘X-Box’ theory, however, that OMing satisfies the average male’s innate manual urge to twitch, twiddle and jerk, with the clitoris standing in as the ultimate joystick. For the man, poised with his finger on the hot spot, the woman has become the ultimate gaming device. While he masterfully negotiates one of the most complex biomorphic systems in evolutionary history, his payoff lies in having total control of another human being. The woman’s body is a silver neuron surfboard that he will use every ounce of reflex and training to keep riding the crest of delight. Instead of beeps and sirens, he’ll know how well he’s doing by her keening, her moans, the fluttering of her hands, and her involuntary contractions.

To me, orgasmic meditation was the perfect complement to the social isolation of the internet, where young people passionately interact with each other via Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, but never have to share physical contact. With OM, the process works in reverse: two people can touch in the most intimate way possible, but it isn’t necessary for them to know each other, or even talk, outside of the bare minimum of words necessary to convey: ‘A little faster. A little more to the left.’

Reserving and tending of orgasm isn’t rare and unheard of, but might be a universal human practice

Of course, the seemingly counterintuitive idea of withholding or even denying climax in order to achieve pleasurable states that exceed orgasm goes back long before Daedone. In the Mandarin court 1,000 years ago, Taoist dandies learned to withhold their jing or ching (ejaculation) during intercourse, not only because they believed that retaining semen would make them live forever, but because sex without orgasm was infinitely more pleasurable, and allowed their partners more time for sexual fulfilment. Male climax, except in the service of creating a baby, was considered draining and depressing. ‘When ching is emitted, the whole body feels weary,’ warned The Classic of Su Nu, an 11th-century marriage manual. ‘One suffers buzzing in the ears and drowsiness in the eyes; the throat is parched and the joints heavy. Although there is brief pleasure, in the end there is discomfort.’ Similarly, in medieval India, male and female adepts of the Tantric sex cult refrained from climax using muscle control they learned from yoga. During intercourse that could last for hours, accompanied by chanting and pungent clouds of incense, couples would rise to a timeless ecstatic state in which they transubstantiated into gods and goddesses of the Hindu pantheon, and at the highest point switched genders.

Curiously, Christian traditions of sex without orgasm go back even farther than those originating in Asia. The early Gnostics practiced a kind of ‘bodily union without orgasm’ or sacred embrace, as an ecstatic spiritual exercise and to form all-too-close connections between the priests and their ‘spiritual wives’. Gnostic males might have been partly motivated by the fact that intercourse without ejaculation can be a workable form of birth control. According to the Gnostic Gospel of Philip: ‘All those who practise the sacred embrace will kindle the light; they will not beget as people do in ordinary marriages, which take place in darkness.’ The practice grew so widespread that Saint Jerome found it necessary to condemn it in a letter: ‘Even if your own consciences acquit you of misdoing, yet the very rumour of such brings disgrace upon you.’

The Romans of Petronius also might have deliberately suspended orgasm during sex, and a steamy passage in the novel The Plumed Serpent (1926) by D H Lawrence – in which his heroine continually rejects ‘the white ecstasy of frictional satisfaction’ with her lover for something else, ‘the new, soft, heavy, hot flow, when she was like a fountain gushing noiseless and with urgent softness from the volcanic deeps … dark and untellable’ – hints that enhanced proto-orgasmic states could occur well past the Edwardian era, at least among a certain sexual elite. Such examples show that reserving and tending of orgasm isn’t rare and unheard of, but might be thought of as a universal human practice, liable to pop up anywhere and at any time.

As early as the 1950s, the Zen philosopher Alan W Watts, a gentle, hyper-educated British transplant who lived in San Francisco and hosted a popular public radio programme, was spending a lot of time thinking out loud about the problem of man and woman, and therefore of orgasm. He noted that the contemporary sexual landscape was a dismal wasteland. According to Alfred Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948), the vast majority of American males flabbered themselves out orgasm-wise in two minutes, and not a few within 10 or 20 seconds. Orgasm under those conditions was a ‘bestial convulsion’, Watts thought, good for relieving tension, but little else, showing how far we were spiritually cut off from the fundamental there-ness of life. ‘The greater part of sexual experience in our culture falls far short of its possibilities,’ he concluded. ‘The encounter is brief, the female orgasm is relatively rare, and the male orgasm precipitate or “forced” by premature motion.’

For an antidote to this sorry state of affairs, Watts reached far into the misty past. He felt that knights returning home from the Crusades might have brought back with them Tantric-style sexual traditions that had drifted westward, possibly through Persia. Among these knights, the Cathars, a heretic group active in southern France and northern Italy, practised a form of idealised love, defined by Watts as ‘prolonged sexual union without orgasm in the male’, in which a knight would embrace the naked form of his true love throughout the night (often, tragically, she was the wife of his prince) while holding back from the final crisis. ‘He knows nothing of donnoi (pure love) who seeks to fully possess his lady,’ as a poet wrote. Such notions of romantic or courtly love, spun down through the centuries by the ballads of medieval troubadours, were eventually taken up as official doctrine by the church, which was one reason why marriages are made for love today rather than arranged like business contracts as they often were in the Middle Ages.

If followed with an open mind, Cathar-style lovemaking still had use, Watts thought. His version, which he called ‘contemplative love’, allowed the full exploration of ‘spontaneous feeling’ between a man and a woman through prolonged Zen-like sexual encounters in which ordinary climax wasn’t the primary goal. Watts compared the subtlety and richness of contemplative lovemaking to the ‘most intense aesthetic delight’ found in brewing and sharing tea with friends or encountering a craggy rock in a garden.

Orgasm would be not the paltry ‘sneeze of the loins’ but ‘an explosion whose outermost sparks are the stars’

Watts gave very specific instructions as to how this was to be accomplished. One might lie face to face in the missionary position, or sit cross-legged, as if meditating, the woman’s legs around the man’s waist, her arms around his back – naturally this position made it almost impossible to move at all, which was all the better. Or one could take the advice of Rudolf von Urban – a Viennese psychiatrist living in Los Angeles in the 1950s and ’60s who promoted similar modes of orgasm abstinence – and lie at right angles to one another.

In any case, once the genitals were engaged, the point was to remain as still as possible, and to wait with the mind and senses fully open to ‘what is’, communing psychically. ‘It becomes possible to let this interchange continue for an hour or more,’ Watts wrote, ‘during which the female orgasm may occur several times with a very slight amount of active stimulation, depending upon the degree of her receptivity.’ Or both sides might prefer to remain completely stationary, ‘and let the process unfold itself at the level of pure feeling, which usually tends to be the deeper and more satisfying way’. In the end, should orgasm happen along, unwilled, as if by chance, it would be nothing like the paltry ‘sneeze of the loins’, described by Kinsey, but ‘an explosion whose outermost sparks are the stars’.

In Watts’s words one can hear the plaintive cry of seagulls in the mist, the lap of waves against a houseboat, the thrum of avant-garde jazz in a North Beach coffee shop, and the desperate yearning and striving for godhead and ecstasy through individual action. In the following decade, as his interests branched out from Eastern mysticism into psychedelic drugs and various sorts of sexual exploration, Watts became a spiritual beacon for the counterculture movement, much like his friend and fellow British expatriate, Aldous Huxley, who was living in Hollywood at the time and writing about his experiences taking mescaline. In 1962, Huxley was to publish his final novel, Island, about a tropical utopia whose inhabitants practiced free love using a ‘yoga of love’ very similar to Watts’s ‘prolonged sexual union without orgasm’. Unlike the dystopian Brave New World, published three decades earlier, Island showed the direction that Huxley felt the world should be heading in, towards truth and freedom and away from the cycle of sexual dissatisfaction in which our culture found itself trapped.

While Watts didn’t manage to convert the repressed beach-blanket culture of hot rods and back-seat dalliances to the subtle allures of courtly love, his words continued to vibrate among a select few long after his death in 1973. One was the young Daedone who became so enamoured of the erotic philosophy of Watts that she moved to San Francisco to study under one of his protégés. According to her oft-told story, she was on the verge of taking vows of celibacy in order to become a Buddhist nun when she met Ray Vetterlein at a party.

‘When the traffic jam that was my mind broke open, I was on the open road, and there was only pure feeling’

In terms of Daedone’s biography, Vetterlein goes a long way towards explaining how the gentle strumming of contemplative love turned into the antic shredding of the female lower parts characterised by orgasmic meditation. He was a scrawny 75-year-old from Novato, California, with a gravelly voice and a craggy jawline, who was seen as something of a living national treasure by his followers. For half a century, he had done little, apparently, but give women deep, sincere, life-changing orgasms. Vetterlein died in 2011 at the age of 85, and towards the end of his life he had come to see sex as a purely spiritual act. Sexual energy, he would say, was the same energy that joined the stars together in the cosmos and atoms together in your hand, the same energy as the electromagnetic or the strong and weak forces or gravity. Eventually, he learned to make a woman climax just by gently stroking her earlobe, touching her arm, placing his palm on her belly, or even by looking at her from across the room, or so he claimed. He could sustain orgasm in a woman for three continuous hours. ‘I don’t know what the limit is,’ he told an interviewer once. ‘I don’t think there is any.’

By Daedone’s account of the party, with little preamble, Ray had said something like: ‘Take off your pants, honey, lie on the floor and spread your legs. I want to try a sexual technique on you. It will take 15 minutes, and when I’m done you can walk away and never see me again.’ With some trepidation, she complied. At first nothing happened. ‘I was where I always was … in my head,’ Daedone said later in her TedX talk, describing the scene. ‘I was thinking about whether or not I looked good. I was thinking about whether or not I was doing this thing right. I was thinking about whether or not this guy was kind of creepy. I was thinking about whether or not I was going to marry him. I was thinking about whether or not my stomach looked a little poochy.’

Then without warning, as Ray continued rhythmically to stroke her clitoris – up-down, up-down, up-down – she was transported into a timeless revelatory-ecstatic state. ‘When the traffic jam that was my mind broke open,’ she recalls, ‘it was like I was on the open road, and there was not a thought in sight. And there was only pure feeling.’ The experience blew away the tranquility she’d found in Buddhist meditation, and she felt an overwhelming urge to weep and to bring the rest of the world along with her.

Orgasm works its ecstatic ways by triggering some of the deepest regions of the brain, such as the amygdala and the hypothalamus, to produce neurotransmitters that cause pleasure, such as dopamine and oxytocin as well as endorphins. In fact, scientists say that an orgasm is the most powerful event that can happen in the brain short of an epileptic seizure, which to a large degree it resembles. As this potent cocktail of neurochemicals baths our neurons and our organs, our breathing speeds up, our pulse races, and the conscious parts of our brain dealing with stress and anxiety grow quiet. And then comes what the writer Anaïs Nin charmingly called ‘the gong of orgasm’, when all else in one’s mind disappears under an avalanche of sensation.

There is ample medical evidence that orgasms are good for you. For a woman, having regular orgasms can boost the immune system, improve digestion, regulate menstruation, relieve pain, discourage breast cancer cells from developing into tumours, and even make her look a decade younger. For a man, the benefits are similar: regular orgasms can reduce levels of stress, improve memory function, reduce depression, improve sleep, and lower the risk of heart attack and prostate cancer. A man who has three or more orgasms a week (as opposed to the national average of 1.5) can add three years to his life. If he has the will and the stamina, having an orgasm a day will add yet a fourth year.

But ordinary orgasm, as we know it, isn’t a particularly lasting experience. Your eyes close, your lips part, your breathing increases, your muscles tense, suddenly your body floods with a soft, dreamy, syrupy sensation of pleasure, goes through 8 to 12 involuntary spasms or contractions that occur 8/10ths of a second apart, and then, famously, it’s over. ‘Is that all there is?’ asks the Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller song. ‘Is that all there is?’

The fleeting nature of orgasm, followed for some by hollowness and loss can make some of us quite cynical about the experience. In modern literature, the overwhelming urgency and pleasure of orgasm is often paired with the sense of depletion and malaise, especially when it is over. As the writer William S Burroughs said: ‘There is the pleasurable orgasm, like a rising sales graph, and there is the unpleasurable orgasm, slumping ominously like the Dow Jones in 1929.’ Doctors have a name for the post-coital blues: tristesse, after the French word for sadness. Tristesse can strike for a variety of reasons, including anxiety about performance, emotional distance from one’s partner, prior sexual abuse, and guilt and shame due to one’s religious beliefs.

But there’s also evidence that postcoital tristesse might be hardwired in our systems, caused by a withdrawal of the very addictive neurochemicals that make orgasm so pleasurable. The chief culprit, dopamine, floods the pleasure centres of our brains during orgasm so that everything, for the moment, seems beautiful and calm, and we feel at one with ourselves and everyone else, but these neurochemicals soon dissipate, leaving us dissatisfied and depressed. It is no wonder that some people become sex addicts, trying to procure that same orgasmic high over and over again.

orgasm in women reduced blood flow in the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex, causing reduced anxiety

Arguments for OM and the like sometimes devolve into age-old moral oppositions, with ordinary lovemaking with the goal of climax seen as a form of instant gratification (and therefore ‘bad’) while orgasmic restraint is praised as a quest for a higher purpose using self-control (and therefore ‘good’). Some imagine a kind of epic battle taking place within the brain between the easy virtue of the neurotransmitter dopamine, produced by climax, versus the lasting goodness of connection and trust induced by the neurotransmitter-hormone oxytocin, which is created by mothers when they breastfeed and by couples when they hug, and is also supposedly produced in large quantities during Orgasmic Meditation.

These arguments might be exaggerated. But perhaps Daedone and Watts et al put their finger on a significant feature of the US sexual arena when they decided that conventional orgasm – that is, climax – wasn’t necessarily central to existence, and that one can sometimes do as well or better without. A large-scale scientific study of US sex habits – Sex in America: A Definitive Survey (1994) by Robert T Michael, John H Gagnon, Edward O Laumann, and Gina Kolata – found that the majority of women (and some men) didn’t have regular orgasms. The surprising find was that most were pleased, even enthralled, with their sex lives. ‘Our data was unexpected. Despite the fascination with orgasms, despite the popular notion that frequent orgasms are essential to a happy sex life, there was not a strong relationship between having orgasms and having a satisfying sexual life.’

What happens scientifically when orgasm is delayed or denied, as in OM, is a little hard to pin down. To find out, I paid a visit to the laboratory of Barry Komisaruk at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Komisaruk, 76, is one of the nation’s premier orgasm researchers. I found him buried in one of his own fMRI machines donating an orgasm to science so that its effects on the brain could be read in real time. He has found that vaginal stimulation produces pain-reducing peptides in the body. He also discovered a previously unknown neural pathway from the genitals to the brain through the vagus nerve, an ancient nerve that wanders up through the body touching each of our important organs on its way to the brainstem. This wandering aspect might explain why having orgasms (or perhaps nearly having them) is so healthful to human physiology. In one study, Komisaruk observed that women who’d had devastating accidents that severed their spines were still fully capable of having orgasms.

One thing that Komisaruk hasn’t observed is the anxiety centres of the cerebral cortex shutting down, something that was seen during stimulation by the neuroscientist Gert Holstege of the University of Groningen in the Netherlands. Holstege placed 12 healthy young heterosexual Dutch women into PET scanning machines. Then he asked their boyfriends to bring them to orgasm. This they did, upon command, up to three times (those women who attempted to fake their orgasms were easily caught by the pressure-sensitive plugs the doctor had inserted in their rectums). Holstege found that orgasm in women reduced blood flow in the left lateral orbitofrontal cortex, causing reduced inhibitions and anxiety – in effect, putting them into a meditative, ecstatic state. Theoretically, in primitive times, a woman found it useful to be able to ignore danger signals all around her at least long enough for the sex act to be completed. But Komisaruk, using more sophisticated fMRI scanners, hasn’t been able to duplicate Holstege’s finding. He remains a skeptic of orgasmic meditation as well. ‘I like to get where I’m going,’ he told me during our interview. ‘These women are on a slow boat to nowhere.’

Daedone announced that we’d now take an hour’s lunch break, and when we came back we’d be issued nests of pillows and small vats of lubricant, and taught how to play a woman like a cello ourselves. We filed out on shaky legs, blinking, into the stark sunlight of the East Village winter afternoon, somewhat stunned. Instead of following one or another of the chattering groups, I went alone to a nearby Indian restaurant and ordered a large-size bottle of Kingfisher beer.

I needed to step back a little, I thought. I considered myself a reasonably worldly man. I’d survived the unbridled debauchery of a mid-century suburban teenagerhood, spent a year in an art-school dormitory in Kansas City where exotic strains of chlamydia were traded like Pokémon cards, and had my wedding night on an Alaskan fjord where the unrelenting rays of the evening sun allowed no shadow to throw a modest veil over the naked truth of what we were attempting. I’d attended the births of all three of my children, during the third of which a placental abruption had painted the walls to resemble the cathartic final scenes of the slash epic Friday the Thirteenth. But Daedone’s demonstration that afternoon had frankly pushed me past my erotic comfort zone. Was I really ready to play Charlie Mingus on the bass strings of a stranger – comely as many of the women in the audience had been?

It would be perhaps too easy to dismiss Daedone’s distinctly entrepreneurial operation as New Age nonsense, dressed up in some very shaky 21st-century feminism and such recent buzzwords as ‘mindfulness’ and ‘flow’. But other practices once considered untenable products of fuzzy minds, such as meditation, vegetarianism, yoga, psychoanalysis and, yes, even feminism had moved from the hazy margins of society to the centre and were fully accepted now. Perhaps it wasn’t too far-out to consider orgasm less a mathematical constant, like pi, that remains the same in every case, and more a variable that can be cracked open, parsed, stretched out to the length of a Miles Davis trumpet solo, keyed, modulated, imbued with tonal variations, compressed and expanded. At best, Daedone might bring some slowing down to the fraught and frantic proceedings of the American bedroom. At worst, a couple might pursue a preposterous fad that, though it might bring disappointment, would certainly bring them no harm.

I drained a quart of beer while pondering these questions. My strongest urge was to go home and tell my wife what I’d just seen. I rose to my feet, a little unsteady, and stumbled to the subway.