Unbound by human owners and the constraints of petdom, they live the doggiest of dog lives: they sleep when they want, mingle with friends they choose, pee when the urge hits, and eat when hungry – as long as food can be found. Wandering the streets of Chennai in southern India, we saw them dozing alone or in company on pavements, seeking shelter from the heat under a van, watching children playing on the beach, or being cared for by local residents. Part of Indian street life, these free-living dogs stand in stark contrast to the culture of pet ownership found in the West. Not only do they defy the image of the out-of-control and marauding canine stalking the sensationalist articles of 19th-century newspapers in Western Europe and North America, they ask us to question our sanitised cities and stewardship of a world with nature at so much risk.

India’s robust street dogs also challenge the supposed superiority of pedigree that dominates dog breeding today. One of us recently adopted a street dog from Romania. Bell Kanmani was brought to the United Kingdom by one of the many charities picking up street dogs there and finding them new homes abroad. While walking her in the UK, Bell Kanmani’s human is regularly confronted with the question ‘What breed is your dog?’ The response that she is just a ‘dog’ only serves to prompt further speculation about what mix of breeds she might be: everything from a collie to a Jack Russell. Having grown up in India, Kanmani’s human finds strange, and rather disturbing, this idea of dogs as necessarily belonging to a particular breed or mixture of breeds. She is familiar with dogs who have lineages free of any human breeding, not necessarily belonging to humans or doing what humans command them to. These unowned and breed-free dogs are now often known as street or village dogs, or – our preferred term – free-living dogs.

Too often in the West, dogs are seen through the prism of pedigree, and connected to their owner via collars and leashes. All too often, the realities of how dogs and humans live together in the Global South are overlooked. As a country with a significant street-dog population, India is a good place from which to explore how humans and canines share street life in cooperative ways that move beyond images of free-living dogs as dangerous.

Exposing the reality is crucial given rising media calls for culling Indian street dogs, exposing them to rhetorical and actual violence. The condemnation of street dogs as risky and unwelcome is rooted in colonial attitudes, and overlooks complex and varied everyday interactions, often positive, between dogs and humans. Discussing their lived experience will help the dogs themselves, and also help us reflect on how humankind can share the planet with all the other creatures who live on it.

Free-living dogs pose a fundamental challenge to the idea that animals must serve some human purpose. Their lives contradict the Western understanding of dogs as creatures who belong to a particular breed or a mixture of breeds. They show that ‘breed’ is only one way of thinking about dogs, even if it is dominant in the West and has spread across the world.

The idea that ‘legitimate’ dogs must belong to a breed based on appearance and conformation to physical standards comes from mid-19th century Britain, including the upper-class fox-hunting kennels and the working- and middle-class penchant for ‘dog fancy’ shows. Dog shows and the creation of the Kennel Club in 1873 provided the arenas and infrastructure for dog breeds to be displayed and their lineages recorded. Kennel clubs and dog shows spread across Europe and North America, positioning breedless street dogs as lesser dogs of unsavoury and degenerate appearance and lineage. Colonialism spread breed ideologies to Africa and Asia. In colonial India, the British imported ‘purebreed’ dogs, establishing Kennel Clubs and dog shows that allowed British and local elites to mingle; although some Indian dogs were entered into competitions, they were dominated by British and European breeds.

Yet dogs existed before breeds, and most dogs living on this planet today cannot be understood in terms of breed. These are the dogs we call free-living dogs. Other names that have stuck include ‘stray’, ‘tramp’ and ‘cur’. These terms positioned free-living dogs as degraded and disgusting, creatures who should be killed.

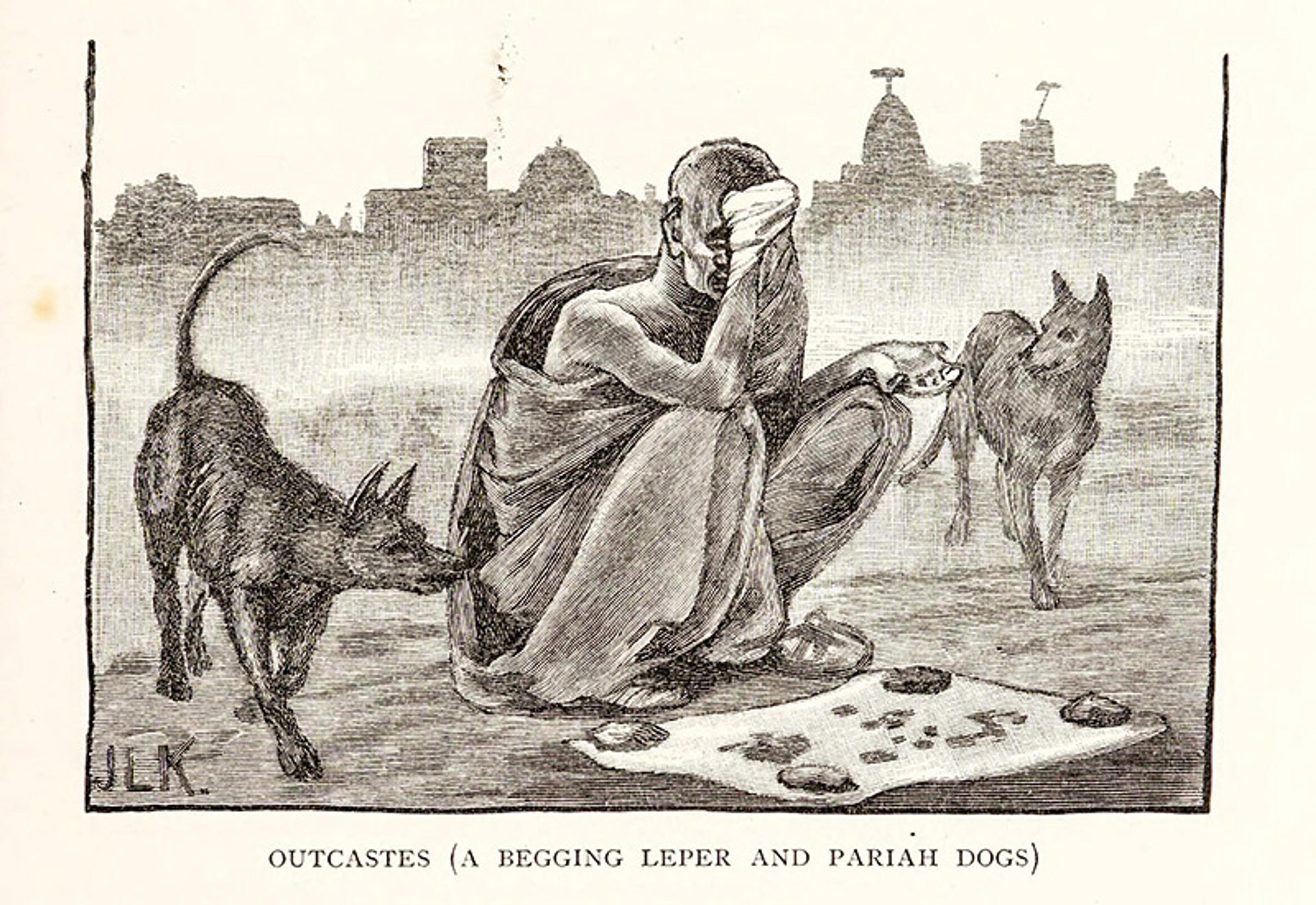

In India, a country with one of the world’s largest street-dog populations, these dynamics have played out in vivid and illuminating ways. Labelled ‘pariahs’ by the British, street dogs were viewed and treated as outcast in the colonial period. The term’s etymology lay in Paraiyar, the former name of a caste-oppressed community (who are now known as Adi Dravida) from southern India (in what is now Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Sri Lanka) who drummed at weddings, funerals and other occasions, alongside performing other menial tasks (‘drum’ in Tamil is parai). Framing this group as victims of caste oppression, the British nonetheless disdained the Paraiyars’ supposed immorality, drunkenness and brutishness, and used the term ‘pariah’ to refer to outcasts, human and nonhuman alike.

The British introduced this term into Indian law, and saw ‘stray dogs’ as fundamentally illegitimate

In the British imagination, ‘pariah’ dogs represented the decline and decadence of India. Visiting Patan in North Gujarat in 1926, the writer and theologian Alban G Widgery lamented in The Times of India how this former stronghold of Rajput rule was now infamous as a bastion of ‘disgusting’, ‘lazy’ and diseased ‘stray’ dogs who were a formidable ‘menace and a challenge’. Widgery blamed the town’s Jain community for this sorry state of affairs. Jains’ spiritual respect for all life prevented effective control of dogs: ‘nevertheless it is a cause for surprise that the adherents of a religion whose ascetics are conspicuous for their cleanliness and for their ethics of kindness should tolerate the existing conditions.’ For Widgery, the apparent contradictions and irrationality of Indian religious beliefs had produced a public health crisis and a revolting spectacle. Widgery’s views were far from unique, and ‘pariah’ was bandied about in colonial newspapers, reports and books. The term was also applied to street dogs in other British colonies, as well as in Britain. Deemed worthless, ‘pariah’ dogs became targets of violence when British soldiers stationed in India amused themselves by shooting them.

From Beast and Man in India: A Popular Sketch of Indian Animals in Their Relations with the People (1891) by J L Kipling. Courtesy the Wellcome Library

The term ‘stray’ further marginalised Indian street dogs by branding them creatures who had roamed from their rightful place within a human dwelling. The British introduced this term into Indian law, and saw ‘stray dogs’ as fundamentally illegitimate, in contrast with the pet dogs they brought with them. Dog-care books of the era encouraged British dog owners to keep their pets within their home; and municipal authorities, goaded on by newspapers, introduced legislation that subjected free-living dogs to impoundment and slaughter. Throughout colonial India, municipal authorities deployed different ways of killing dogs: poisoning and shooting by police or clubbing, most often carried out by caste-oppressed men. Such methods were opposed by some British people as well as Indians. Demonstrations, riots and strikes broke out in Bombay when the Parsi community took umbrage at the extension of dog culling laws during the summer of 1832. British authorities sought more effective and less controversial ways of eliminating straying dogs. In Madras, a lethal chamber was installed in the dog pound, as was one in the Military and Civil Station of Bangalore’s pound. But ‘humane’ killing remained controversial, with demonstrations once more breaking out in Bombay in 1916 when a lethal chamber was introduced.

Lurking behind the condemnation of free-living dogs was the spectre of rabies. Although pet dogs were known to spread this viral disease, 19th-century doctors, public hygienists, journalists and veterinarians in the Western world lined up to blame street dogs for spreading this fearsome illness. Branding them dirty, diseased and disorderly, they argued that street dogs’ mobility and abundance represented a public health threat to be managed through muzzling, dog taxes, impoundment and culling. From Singapore to southern Africa, colonialism spread such attitudes and practices across the globe. In India, they stuck to ‘pariah’ dogs who were viewed not only as unsightly but dangerous creatures, further justifying the capture and culling of straying dogs.

The legacy of British rule continued well into the post-independence period, until 2001 when the term ‘stray dogs’ was replaced with ‘street dogs’ in Indian law, and killing as a means of dog control became illegal. The Animal Birth Control (Dogs) Rules (2001), a central government notification, codified the right of dogs to exist outside of human ownership. Neutering and anti-rabies vaccination programmes came to replace culling as a means of managing street dogs, even if extra-legal culls have continued, such in Bengaluru (Bangalore) in 2007 and Kerala in 2021.

The status of dogs in India now contrasts sharply with that in Western countries, where any dog found wandering outside on the street is considered stray and liable to impoundment and being killed if not retrieved or rehomed. Widespread culling of ‘straying’ dogs and the introduction of neutering has virtually eradicated free-living dog populations in the West. In places such as India, dogs have many more opportunities for life than in places like the UK where they are allowed to exist only under human ownership. The idea that dogs belong in public spaces is also reflected in vernacular terms for free-living dogs – theru nai in Tamil, galee ka kutha in Hindi, vidhi kukka in Telugu – all of which mean ‘street’ and not ‘stray’ dog.

While Indian law and public attitudes recognise the legitimacy of street dogs, transnational animal welfare and public health ideas continue to challenge their status as autonomous free-living animals. While street dogs in India are not killable, they are often treated as needing either control or rescue, and sometimes both. Norms about public health, nuisance and development cast free-living dogs as creatures to be controlled through ‘removal’ to unspecified locations and fates.

Alongside rescue and adoption initiatives meant to bring the benefits of petdom to street dogs, one finds neutering and vaccination programmes directed at controlling their populations and reducing the incidence of rabies.

Neutering refers to castration in males and ovariohysterectomy in females, both major surgeries with long-term impacts on the individual animal’s life. The side-effects of surgery are only increased by the serious harms that can come with capture, transport and kennelling. Neutering is nonetheless seen as best practice in animal welfare for dogs because of Western norms about the ‘inferior’ quality of life experienced by dogs who are not owned by humans.

A closer look at free-living dogs offers a different picture. Far from scrounging around for scraps all day, such dogs in India spend most of their time relaxing and sleeping (and sometimes in unusual places, such as squeezed between two motorbikes).

This is not to say that their lives are a bed of roses: they have to search for food, water and shelter without guarantee of success, and they are subject to accidental and intentional human-induced harms, such as road traffic accidents, being chased away, culling, and deliberate cruelty.

Nonetheless, they lead relatively autonomous lives. They get to pee and poop when they need to (instead of being restricted to times specified by humans). They get to choose their own lovers and friends (human, canine, feline), play when they want to, be solitary when they want to. They have at least some opportunity to escape unwanted or noxious human attentions, unlike pet dogs, who are bound to the confines of human ownership regardless of its quality. The lives of free-living dogs are not always better than the lives of human-owned dogs, but the reverse is equally not the case.

The way people interact with these dogs is variable and complex. Conflict over the issue is particularly heated in Chennai, where we surveyed the population to see how people felt in 2017. A majority of those we spoke to were indifferent to street dogs and barely noticed them: ‘Each street has around 2-3 dogs… but I have never thought about them very much,’ said Kanakam of Chennai.

Many of those from the middle and upper classes saw dogs as nuisances that barked and chased. ‘I don’t think in any other country in the world there are stray dogs. Dogs always have some owners,’ complained Mini from Chennai. Others took the sentiment further, likening free-living dogs to humans who live and work on the streets, insisting they should all be removed.

Even those who saw the dogs as pests recognised them as vulnerable creatures with a right to live in the city

Such friction between traditions of multispecies cohabitation and new(er) ideas of a more sanitised and developed society produces support for neutering or culling.

Yet others had companionable relationships with the animals. Karuppiah, a pavement dweller in Chennai, discussed the street dogs in his neighbourhood: ‘We give them porai [hard bread] biscuits. So they get accustomed to us … We interact, no? That dog plays with us with love, no? Sleeps next to us. After we are asleep, they sleep on our legs.’

Velu, a waste-worker, said: ‘I give them whatever food I find in these bins. Sometimes you get food, sometimes you do not. When you do not get, there will be dogs looking at you longingly for food … Romba kashtama irukkum [it makes you feel very bad].’

Even those who claimed the dogs were pests usually recognised them as vulnerable creatures with a right to live in the city; the words paavam (vulnerable) and jeevan (life-form) were frequently mentioned in our Chennai interviews. In the words of Gokul from Chennai: ‘I think they are a nuisance. They aren’t trained; they eat from the garbage and end up scattering garbage everywhere. The ones sleeping on the roads are a problem for pedestrians as well … [but] you can’t just remove them from the street. They have a right to live there as well.’

We found that a majority agreed that street dogs were a problem (71.6 per cent) but a majority also believed that they have a right to live in public places (78.8 per cent), and that they are paavam (79.3 per cent).

There exists a wealth of knowledge, especially among those who live and work on the streets, on how to interact with street dogs safely. Ramu, a waste-worker explained: ‘You should not get scared [padaravey koodathu]. You should not run or make any sudden movements. They will come very close, but they will not bite. Be casual … they will go away. They will keep barking but after a while they will stop … Talk to them. Say things like “What do you want?” Or gently say “Keep quiet.” Next time make sure you feed them something. But, first, you have to be casual with dogs. Do not fear them at all.’

The lives of India’s street dogs challenge us to examine mindsets and culture in the age of the Anthropocene, where humans dominate and nature is beset by the climate crisis and habitat destruction worldwide. Before we save faraway wildlife, we may need to truly see the dogs who live free, near our homes. Free-living dogs can be pests and threats to human health, but they can also contribute to human wellbeing through companionship and relationships of mutual care. In India, everyday acts of care, such as stopping to fuss over two local dogs while whizzing around the metropolis, point to how humans and other animals can live alongside each other in the human-built world.

The dogs on India’s streets provide useful lessons on sharing the planet with other creatures – from wolves and bears to snakes and tigers – who are often more valued but certainly more dangerous to us. Cohabitation entails both coexistence and conflict. It is not easy to live with or live alongside others, including humans, but everyday interactions over long periods of time can incubate an ethos of mutual tolerance on a human-dominated Earth.

Most creatures protected or valued as ‘wildlife’ in today’s world were once exterminated as threats or as valueless. Animals like wolves and beaver are being persecuted yet again when their populations are revived thanks to conservation. This is because they find themselves in human-dominated and modified landscapes where there is no memory or knowledge of how to share spaces and lives.

Instead of worrying only about endangered species, perhaps we should focus on animals in our midst. Learning to live with and respect free-living dogs, rats, gulls, cockroaches and mosquitoes might well be a crucial stepping stone for learning to protect the lions, pandas and elephants at risk and far from home.