Listen to this essay

20 minute listen

If all the writing that claimed to ‘subvert’ our expectations actually did so, society would have long since learned to live without expectations. The word has become a staple of book reviews and jacket blurbs, a foundation for how undergraduates understand the value of a text, and an aspiration for writers hoping to establish a reputation for colouring outside the lines. This commercial and institutional ubiquity is made stranger by the fact that, except in rare discussions of theological corruption, this very old word has become associated with literature only in the past 70 years. In 1956, the Canadian critic Hugh Kenner became the first to deploy it as a literary-critical term in an essay in The Sewanee Review: he claimed that the Irish poet W B Yeats had ‘subverted’ a tradition. Kenner was using the word in the sense it had since its entry into English via the Wycliffe Bible: to raze, to destroy, to overthrow, or to corrupt.

The fourth in that list is crucial: ‘to corrupt’ hints at the distinction between subversion and revolution. We might call a revolution an inversion of the social order that happens only once Hierarchy No 1 has been weakened enough that Hierarchy No 2 can come into power. It would be impossible for a revolution to be both successful and secret. Subversion, on the other hand, affiliates success with secrecy. Subversion is effective precisely because it takes a keen perception to point it out: it implies corruption so subtle that it eludes notice, even when you think you’re looking.

The idea that Yeats subverted a tradition, though, still implies that traditions are susceptible to wholesale destruction, one that may begin obliquely but end in the rise of a completely new tradition. But literary traditions are not so brittle as that. The unique power of literary tradition, unlike philosophy or science, is that literature can respond to its predecessors without invalidating them, can contradict them without competing with them. When we call literature ‘subversive’, we don’t mean it in the destructive sense that it was used until Kenner. Literary subversion is a radically different phenomenon, in which predecessors are incorporated into their own repudiation.

Many constellations of literary work show the nature of literary subversion, but for a clear and etymologically appropriate example, look to depictions of the Christian Hell. Hell is a good place to talk about subversion because it’s such a uniquely literary place: it is perhaps the only location that appears in a wide swathe of literary traditions but never appears (to the living) outside of fiction. It’s easy to get bogged down in the sometimes productive, sometimes distracting differences between James Joyce’s Dublin and the Dublin that existed in 1904, or in the ways that Shakespeare’s plays interact with the geography of Italy. In comparison, discussing depictions of Hell is a cakewalk. Theologians, the reigning authorities on Hell, prefer to describe it as a position of infinite distance from the Divine. Not discounting the horror of that concept, it leaves quite a bit of room for competing literary depictions to serially subvert one another without being harassed by the pesky reality of the physical world.

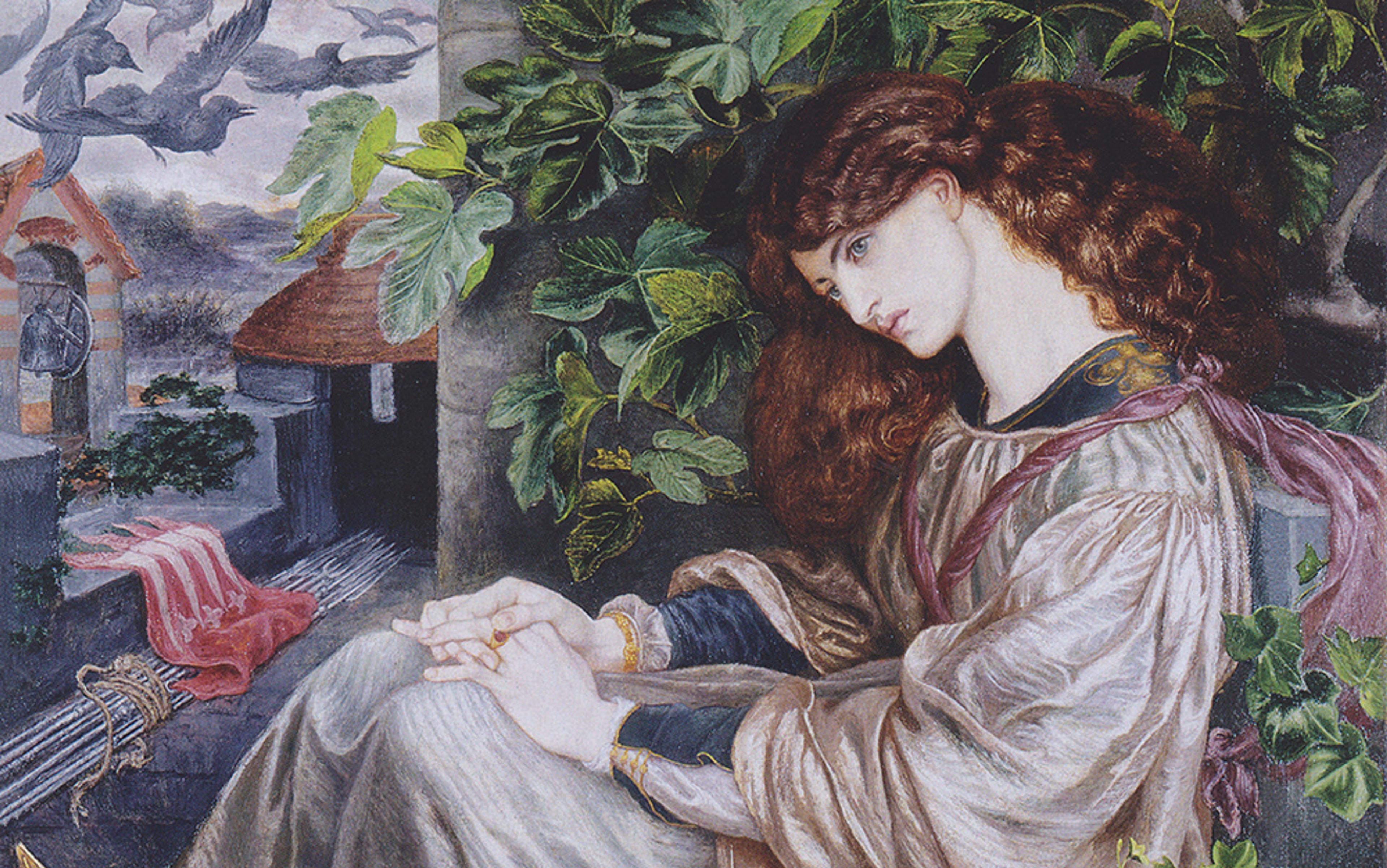

Dante Alighieri’s Inferno responds to the classical epics in what is perhaps the most famous literary Hell, taking readers into the Christian realm of eternal punishment in the same way that Homer and Virgil took readers into Greco-Roman Hades. Despite the Christian theology that informs the project as a whole, the poem retains many features of its predecessors. Dante shares the page with Virgil himself, employs the three-headed Cerberus as a watchdog in the Third Circle and, in perhaps the most surprising among a gamut of other debts, shows sinners punished in a manner corresponding to their crime. The individuality of Dante’s Hell is still difficult to grasp: for example, not only are those who were buffeted by desire in life condemned to an eternal hurricane in death, but Hell itself is organised along Dante’s own priorities. His sympathy for lovers, like Paolo and Francesca, puts them in the early, less severe regions of Hell, while his disgust with political connivance, like the machinations of Guelph factions that determined the course of his own life, puts intriguers near the centre of the Pit.

Literary influence and political commentary are not at all disconnected concerns

Dante is subversive today because the idiosyncrasy of his Hell still comes across to contemporary readers. If the Inferno had actually subverted, in the sense of ‘destroyed’ or ‘corrupted’, the ideas of Hell that came before it, readers today would have no stake in Dante’s innovations. Our ideas of Hell would have been replaced entirely with Dante’s vision; when new readers open the Inferno, they would find something already familiar. Indisputably, Dante has influenced our assumptions about the afterlife, but his image of Hell retains too many features of the Greco-Roman Hades to align entirely with what readers often expect from divine punishment in the 21st century. In fact, retaining Cerberus and King Minos – and all the other features of classical myth that appear in the Divine Comedy – shows how deeply literary subversion differs from the original meaning of the word. Dante is not compelled to destroy what came before. His poem builds on its predecessors, and makes the relationship between past and present clear through the figure of Virgil guiding Dante through Hell.

To give the older sense of the word every opportunity to prove its relevance, it’s necessary to consider literary subversion’s ability to destroy something other than texts that came before: we should look for the subversive impacts that texts have on the political or social world to which they respond. Literary influence and political commentary are not at all disconnected concerns. Dante’s restructuring of Hell is itself a response to the Guelph factions in early modern Florence. In late-medieval Italy, the ‘White’ and ‘Black’ Guelphs warred over a number of thorny political issues, above all what role the pope should have in the affairs of Florence. The Black faction, supporters of papal power, triumphed on the temporal plane, but Dante, a White partisan, won the literary war: he placed his Guelph enemies deep in Hell and even found a permanent home for Pope Boniface VIII in the Eighth Circle, where they all remain 700 years later.

To the extent that we remember the Guelphs at all, it is largely because of the political subversion of Dante’s great poem. In exacting this revenge, however, Dante doesn’t destroy his political enemies. His literary condemnation also enshrines them, so that literary subversion, if it happens here, is characterised less by destruction than by incorporating what you subvert into what you build. The next major poetic depiction of the Christian Hell, however, is an even more emphatic riposte to its immediate political scene.

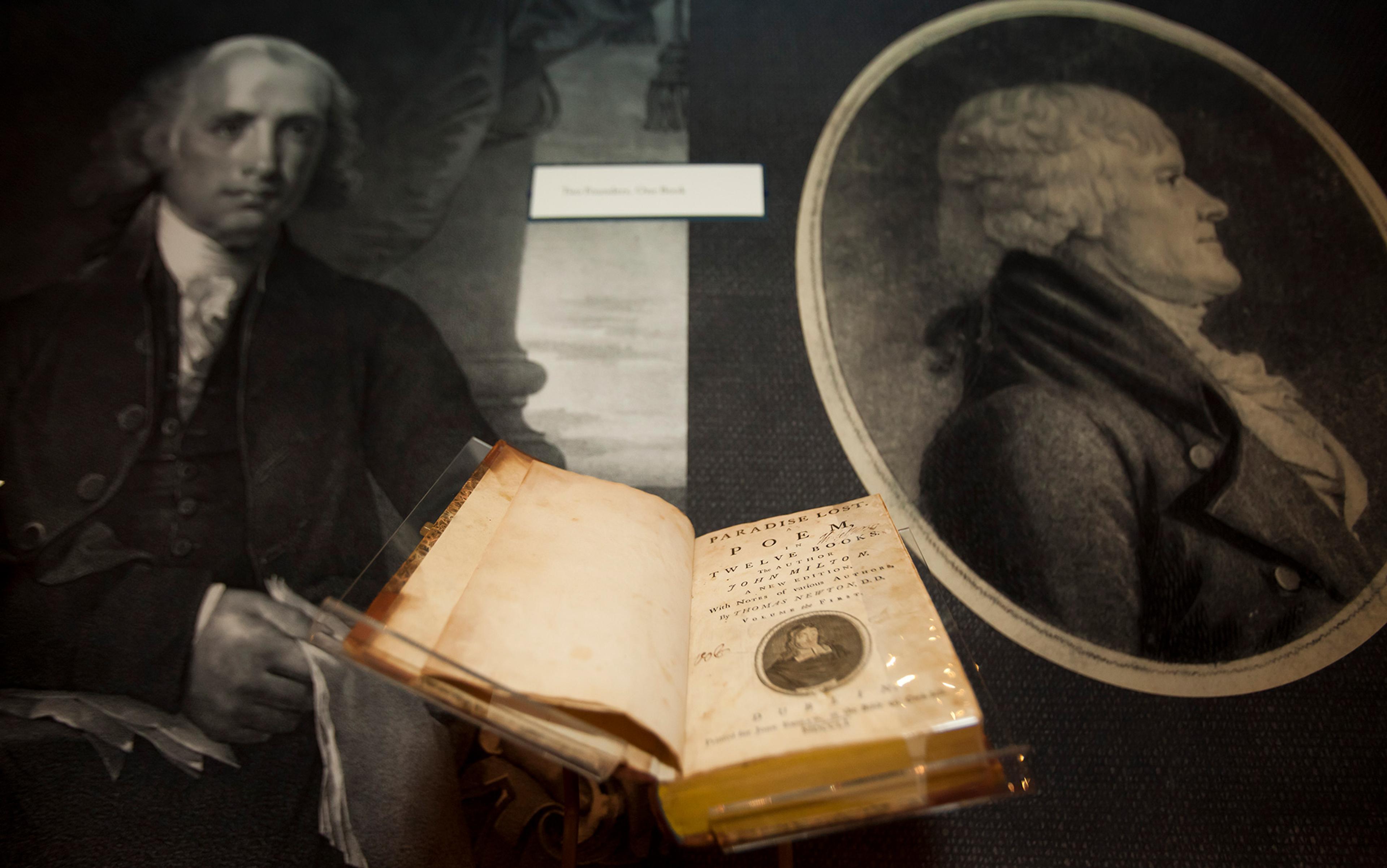

John Milton’s Paradise Lost forgoes the explicit reliance that the Inferno has on its literary predecessors in favour of a pointed commentary on monarchism. Satan wakes, in Book 1, in ‘a dungeon horrible’ filled with flames that throw ‘no light, but rather darkness visible’, and builds Pandaemonium – a kind of satanic parliament – with his cohort of fallen angels. In a dazzling display of political savvy, Satan convinces his fellow demons he’s doing them a favour by going to Earth to corrupt mankind. Readers primed with a background in Milton’s anti-monarchical politics will easily find an expression of that politics in the poem. Satan is styled as Hell’s monarch, and the parliament he convenes there in Book 2 serves as a biting critique of monarchical power:

[Rising, Satan] prevented all reply;

Prudent, lest from his resolution raised,

Others among the chief might offer now

(Certain to be refused) what erst they feared,

And, so refused, might in opinion stand

His rivals, winning cheap the high repute

Which he through hazard huge must earn.

Satan’s power over his fellows is totally rhetorical. Opinion is the source of his power, not Divine Right, though we’re told again and again that Satan was placed above the other angels before his fall. Milton is writing after the Restoration, and depicting the monarch as Satan, and monarchy itself as such a fragile, rhetorically constructed affair, qualifies as ‘subversive’ in the political sense of the word. But even if we take the word in its weakest sense, as ‘undermine’, it implies that Milton’s poem has real political effect. Milton’s poetic influence is undeniable, but I don’t think many literary critics would suggest Paradise Lost helped to lessen the power of the monarchy. It has sometimes been claimed that the poem influenced the Radical Whigs, who in turn helped to inform the tenets of the American Revolution; this is a real, traceable political effect, but it does less to undermine the regime the poem criticises than to help build something new.

Milton’s jabs at monarchy do less to tear it down than to make a claim for the value of the poem itself

Influence aside, the text itself is more complicated than an attempt to undermine just one political system. The same quote that critiques monarchic power could be taken to critique a parliamentary system: Satan, yes, is devilishly cunning, but aren’t the rivals who might win ‘cheap the high repute’ even worse, as they fail even to make the somewhat dangerous journey out of Hell? The same figurative manoeuvring that makes Satan the king makes these the parliamentarians. After all, this comes towards the end of Book 2, which they have spent debating the proper course for their new domain. Satan is only the last and most successful of a long series of speechmaking devils. If monarchy is being put down here as too fragile, too rhetorical, then parliament – housed in Pandaemonium, a word that has since come to mean a chaotic cacophony – is where mere rhetoric reigns supreme.

Illustration of Satan (1688) by John Baptist Medina from the fourth edition of Paradise Lost by John Milton. Public domain

Milton doesn’t seem to be undermining any political system in a serious way, nor does he seem to turn anything upside down or tear down anything. Just as Dante’s incorporation of classical myth into his Christian poem served to orient readers, Milton’s jabs at monarchy do less to tear it down than to make a claim for the value of the poem itself. The poem is signalling its relevance, its comprehensive critique of the political situation – not just a partisan view, but a send-up of the larger dynamic of the moment – and, most importantly, the poem’s claim is that this material is good fodder for a poem. By digesting the monarchy as an object of critique, Paradise Lost stabilises a version of the monarchy with which the cultural moment can be described. Only once an object is available to tacit understanding – the kind of understanding a literary lampoon relies on – do we start to formulate new approaches to the issue at hand. In this sense, then, Paradise Lost can be said to subvert its political situation. The poem offers a vision of monarchy seen through allegory, and in doing so suggests the need for the culture to move beyond the devilry it describes.

Neither Milton nor Dante destroy what they subvert: Dante’s classical sources are still lurking at the core of our idea of Hell and in the architecture of his poem, and Milton, try as he might, won’t bring down the monarchy with a poem. That doesn’t make them any less subversive. It implies only that literary subversion is distinct from the word’s traditional meaning. Literary subversion’s difference from the older, more destructive meaning of the word makes it possible for blurbs and reviews to rely so heavily on the idea. New writing does not have to supplant the old to subvert it, it only has to offer a compelling difference. Take Milton’s own debt to Dante: he opens Paradise Lost with a dogged insistence that this will be a Christian epic inspired by the Christian muse, where what has come before has relied too much on the Greco-Roman sources. Nevertheless, the freedom to reconstruct Hell to serve your individual literary purposes is a debt Milton must owe Dante, protest as he might against owing anything to a Catholic whose work is all too happy to intermingle Christian and classical material.

This ability to accommodate contradiction is a major distinction between the thinking that happens in literary form and the thinking that happens in science or philosophy. When thinking happens within fictions, it requires no claim on truth, only the possibility of truth. Scientists, asking questions about the existence of alternative dimensions or the life of the cell, are comfortable with the fact that, if they arrive at an answer to their question, they will as a result be claiming that the previous answer was wrong. Philosophers likewise cannot claim the validity of one model of the mind without insisting on the invalidity of all the other models of the mind that came before. Science has revolutions where literature has subversions. Most other disciplinary thinkers are concerned with finding the right answer, with creating knowledge. Literature has no obligation to know anything. Rather, literary depictions of Hell, for instance, are asked only to be internally coherent. If we are told in the opening pages that the sinners in deepest Hell are the murderers, but upon arriving find them to be the politicians, then we usually need an explanation for why the author has replaced one with the other, even if that explanation is simply that ‘politician’ and ‘murderer’ is a false distinction. This relatively low bar of internal coherence allows competing and contradictory ideas to coexist in a literary tradition without cancelling out each other.

Literary subversion as McCrae performs it has a nesting effect

Shane McCrae’s poem New and Collected Hell (2025) relies heavily on inverting and updating tropes from Dante. Where Dante is guided through Hell in a sometimes friendly, sometimes stern way by Virgil, McCrae is guided by Law, a robot seagull who nearly always refers to the poet as ‘shithead’. Like Dante, McCrae chooses what sins are greatest: the heart of Hell is occupied by bank executives who are forced to queue eternally for their turn to be popped, exploding into ‘a pink mush’. Large portions of McCrae’s poem rely on the reader understanding how he is responding to Dante; through other features, like when he styles Satan as ‘the boss’ and God as the ‘the boss boss’ even as he puts executives in the deepest pit of Hell, the poem criticises American cultural values as trenchantly as Paradise Lost criticises monarchy. Similarly, these operate more as framing devices than as compelling observations: on their own, they would amount to a stale critique of corporate power.

The implication of changing Virgil to Law is that we now follow an authority who despises us, disrespects us, wants to harm us – at one point Law works itself into such a frenzy, it lunges at the narrator, stopped only by an unnamed metaphysical prohibition. This depiction of Law is linked to the moral degradation of corporate existence. The last passage of the poem’s penultimate section, after Satan has taken over Law’s body to speak to the narrator and left Law dreaming, is:

Hell stopped

Seemed stopped it was a sign the dream was ending in

Law’s dream the end of punishment

is the end of the world

McCrae’s most interesting literary insights come in details like these, rather than the sweeping subversions that structure the poem. Here the narrator’s dream (the mechanism of his trip to Hell) is tied to Law’s dream, and the hierarchy of the two is confused: by leaving ‘in’ in-line with ‘the dream was ending’, McCrae refuses the caesura that would separate ‘the dream was ending’ with ‘in Law’s dream’. The narrator’s own existence is perhaps part of Law’s imagination, then. The rhetorical hesitancy of ‘stopped/seemed stopped’ becomes more interesting in light of that ambiguity. If Law is not imagined by the narrator, but the other way around, then Hell actually stopping would, from Law’s perspective, be the end of the world. In these few lines the complex guilt of complicity in corporate America is leveraged to point out that we feel a bit of relief that Hell only ‘seemed’ to be stopped.

McCrae’s book is subversive in all the ways Dante and Milton are subversive: he offers clever criticisms of the dominant culture and at the same time makes huge deviations from his literary influences, deviations that are meant, like Dante’s gestures toward Greco-Roman Hades, to tell us something about the version of Hell we’re encountering. However, the fact that New and Collected Hell is so obviously subversive is a testament to how specific our use of the word ‘subvert’ has become. McCrae’s poem does not tear down Dante’s Hell, and when it criticises corporate America it does not pretend that corporate America will care. Literary subversion as McCrae performs it has a nesting effect, so that this newest poem wraps our cultural reality around all the iterations of the Christian Hell in Western poetry that have come before. It offers us, in its unique relationship to the long literary tradition in which it partakes, a reminder of the peculiar power of literature to contain the past without minimising or rejecting its predecessors.

In his introduction to Henrik Ibsen’s plays, the essayist H L Mencken argued that Ibsen’s power as a writer comes from having no ideas that would not occur to the average middle-class person of his time. The thought that Norway’s most famous son gets his power from his utter ordinariness seems slightly insulting in our fame-oriented 21st century, and Mencken is very much trying to antagonise the reader into continuing to read, but his larger point is that literature does not have an obligation to offer something radically new in order to qualify as literature.

Perhaps our understanding of the word ‘subvert’ could use a similar deflation. Literature’s job is not to constantly replace itself: McCrae doesn’t take the place of Dante the way Albert Einstein can shoulder Isaac Newton off the podium. Writers have enough of a job wrapping the insights of their generation around the frames and traditions they’ve inherited without pushing always to do something radically unique. That task will force them to find new modes of expression that accommodate the weight of history, like Dante’s terza rima or McCrae’s idiosyncratic line breaks and repetitions. Mencken said that Ibsen wrote ‘sound plays’. That’s a word we don’t see often on blurbs or in book reviews – and I for one would love to encounter a novel or book of poetry that is far more sound than it is subversive.