This is an historical perspective on the Arab Spring – particularly in Egypt, but generalisable to some extent to other Arab countries – from a historian by education and practice. A peculiar personal experience drew me from being another Egyptian protesting in Tahrir Square in Cairo to the state historian of the Egyptian revolution. Only one week after Hosni Mubarak stepped down as president, the head of the Egyptian National Archives together with the Minister of Culture appointed me as Chair of an official committee empowered to document the momentous popular uprising of January 2011 that captured the attention of the world. I assembled a team of archivists, historians and IT experts. We set about planning how to accomplish the mammoth task ahead of us.

Soon we found ourselves having to find answers to difficult questions: ‘How do we go about collecting people’s testimonies?’ for example. Or, more worrisome, given that we were a government committee: ‘Can we guarantee that the testimonies do not end up falling into the hands of security agencies to be used against the same people who had entrusted us with these potentially self-incriminating testimonies?’

Historical questions presented the most difficulty. When did the revolution end? Did it end with Mubarak’s step-down? With the constitutional amendments of March 2011 that banned the then ruling party, dissolved parliament and called for fresh parliamentary elections? With these parliamentary elections that were held in November 2011? With the presidential elections in June the following year? Given that we were still attending funerals of friends and loved ones, running from one police station to another looking for demonstrators who had been arrested, and still demonstrating to demand the release of our comrades – given all this, was the revolution still going on?

Most difficult of all were questions not about when and how the revolution ended – if ever it did – but when it began and where it originated. Was it launched on 25 January 2011, National Police Day, when we took to the streets to protest against the endemic use of torture in prisons and other places of detention? Or did it begin on 14 January when Ben Ali, the Tunisian President, fled his country to Saudi Arabia, inspiring people in Egypt to say: ‘If the Tunisians could do it, then maybe we can, too’?

Or was its beginning on New Year’s Eve 2010 when Muslims and Copts took to the streets protesting against what they believed was their government’s complicity in the bombing of churches? Or a few months earlier with the beating to death of the young Alexandrian activist Khaled Said, who later became the icon of the revolution? Did it start in 2008 when thousands took to the streets all over the country in solidarity with the striking workers in the industrial town of Mahalla? Or were its origins in 2004 with the birth of the Kefaya (Enough!) Movement, whose members were protesting, week in and week out, against Mubarak’s dictatorial rule?

Did it start in March 2003 when we took to the streets protesting against the US bombing of Iraq and when we occupied Tahrir for a few hours? Or did it begin in March 2000 when the Israeli Prime Minister paid his ill-fated visit to al-Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem, prompting thousands of Egyptian university students to spill out of their university gates to demonstrate in solidarity with the Second Palestinian Intifada?

My colleagues on the committee and I pondered these questions, and probed even more difficult ones.

During the last years of Mubarak’s long reign, were we demonstrating against the President grooming his son Gamal to take over the presidency and effectively transform the republic into a monarchy? Were we demonstrating against the endemic use of torture by the Egyptian police? Were we demonstrating against the debased choice with which Mubarak presented us, whereby he was effectively telling Egyptians: ‘Either accept my torture chambers or Islamist rule’?

Or did the revolution have deeper roots still? Was it, rather, a revolution not only against Mubarak’s 30 black years, but against the July Regime set down 60 years earlier in the wake of the 23 July 1952 revolution? That revolution offered us another debased choice: giving up our constitutional and political rights in exchange for social and economic rights. Were we rebelling to assert our entitlement to have both kinds of rights – constitutional and political, as well as social and economic? Egyptians who took to the streets on 25 January 2011 overwhelmed the police by our numbers, determination and tenacity in just three days. Were we then, on 28 January, the Friday of Rage, doing what we should have done in the wake of Egypt’s catastrophic defeat in the Six-Day War on 6 June 1967, when, instead of asking the Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser to step down and face trial, we begged him to rescind his resignation and remain the country’s uncontested leader?

Or did the revolution have even deeper roots? Perhaps we were protesting against the intrinsic military character of the modern Egyptian state – a state put in place by Mehmed Ali in 1805. Mehmed Ali, a Macedonian adventurer, set about to change the status of Egypt from a mere province of the Ottoman Empire to a special realm that he and his sons could rule for a hundred years. In doing so, he founded an army that would dominate all aspects of Egyptian life and forever change the nature of the country. Were we specifically rebelling against the state that was created as a result of founding this army, an army that forced peasants to serve dynastic interests that made no sense to them, to struggle for causes in which they did not believe, and to die in wars that were not theirs?

These are the questions that I faced when I undertook to chair the committee that was to document the January 2011 revolution. The questions made me see that Egyptians were revolting not only against Mubarak and his cronies, but against a state that, to paraphrase Karl Marx, came dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with dirt and blood. The modern Egyptian state was not founded on the flimsiest notion of constitutionalism or the rule of law. We entered into no social contract that tied us to our ruler, who descended on us with his ilk like vultures ravaging town and country.

It is a state that has repeatedly failed its citizens, is inherently despotic, and suffers from a foundational legitimacy crisis.

For the past 200 years, Egyptians have not spared any effort in rebelling against this tyrannical state. In contrast to what is taught in Egyptian schools, we did not revolt only against foreign invaders, be they French or British. We also resisted this domestic Leviathan by all means at our disposal.

In 1821, and in the wake of higher taxation, more frequent corvée (forced labour) levies, a draconian monopolies policy and, above all, an unprecedented conscription policy, Egyptian peasants revolted in a massive popular uprising in the south. This peasant uprising spread from Qina to Aswan, and 20,000 men and women participated; 4,000 of them were killed. The following year, an equally large uprising spread in the Delta, only to be quelled by six machine guns commanded by Mehmed Ali in person.

In 1844, another large uprising erupted in Menoufia in the Delta, where government warehouses were set on fire and the pasha’s agents taken hostages. There were also cases where peasants were reported to have uprooted cotton plants from their fields, despite the fact that cotton was one of the world’s most valuable commodities. Destroying it would have cost farmers dearly. Then 1863 saw a large uprising erupt in the south of Egypt, in the same area of the 1821 rebellion.

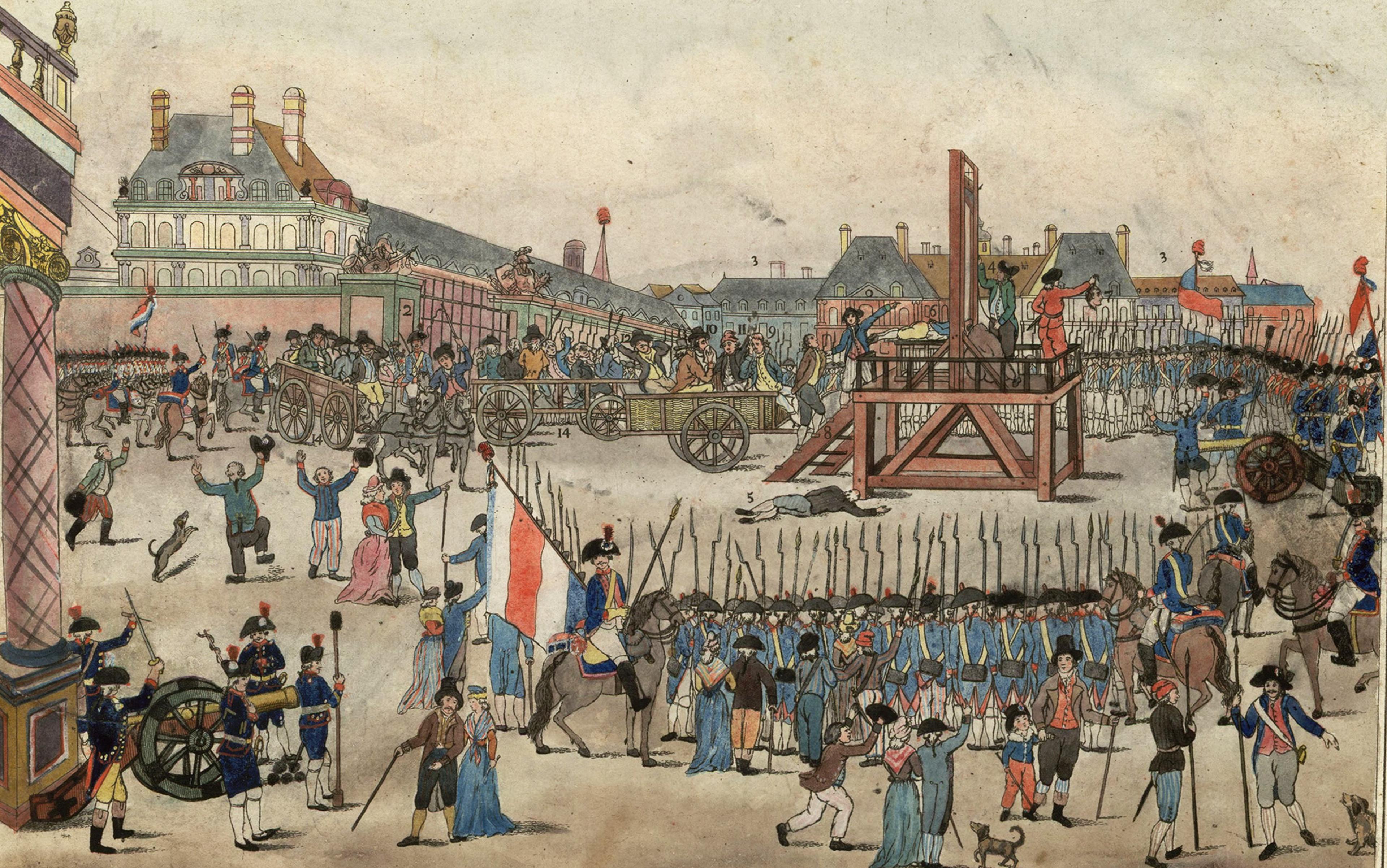

In 1879-1882, people from across Egyptian society rose in a nationwide revolution under Ahmed Urabi. Urabi headed a movement aiming to subject the Egyptian military state to constitutional rule, one that would define the rights and responsibilities of the khedive, the monarchial ruler, and separate his purse from the public purse. In short, Egyptians sought to put limits on the monarch’s unlimited power. The revolution was on the cusp of succeeding, but on 11 July 1882 the British navy answered the khedive’s call for help in confronting the Egyptian people’s constitutional movement. The British bombarded Alexandria and defeated Urabi’s troops, inaugurating a military occupation that would last 70-odd years.

The British occupation dissipated Egyptians’ revolutionary energies. Occupied Egypt had to fight for constitutional rights and for independence at the same time. Two and a half decades after the defeat of Urabi’s army and the landing on Egyptian soil of British troops, Egyptians rose in one massive revolution in 1919 asking for both independence and a constitution. The much‑anticipated independence, however, fell far short of revolutionary expectations, for in 1922 the British handed Egypt a truncated independence that allowed British troops to stay on Egyptian soil, and deprived Egypt from the right to shape its own foreign policy. More seriously, the British interfered in the constitution-writing process, tilting the 1923 Constitution toward the palace, giving the crown powers that enabled it to dominate parliament.

Those of us who were not tortured, imprisoned or exiled found ourselves marching straight to a dark abyss

The period between 1923 and 1952 is often called the golden age of liberal Egypt, but it was neither golden nor liberal. The British continued to maintain their grip over Egypt. The monarch continued to use a constitutional licence allowing him to dissolve parliament at will. Throughout the second quarter of the 20th century, Egyptian political parties failed to develop strategies to defeat either the colonial occupier or local tyranny. The moment was ripe for Egyptians to take to the streets, for the appearance of mass politics.

The political stalemate was broken in 1952, when Gamal Abdel Nasser and his junta staged a coup. They abolished the monarchy, suspended parliamentary politics, persecuted all major political players of the ancien régime, rounded up thousands of communists and sent them to remote prisons, and arrested tens of thousands of Muslim Brotherhood members whom they subjected to indescribable torture. Those of us who were not tortured, imprisoned or exiled found ourselves marching in unison behind our leader, straight to a dark abyss.

Following the June 1967 war, Egyptians rose once more and protested against the lenient sentences that those responsible for this catastrophic defeat had received. A couple of years later, Egyptian universities burst at the seams with demonstrations against a seemingly indecisive policy toward our erstwhile foreign enemy, Israel. In 1977, we took to the streets again in massive numbers against the government’s economic austerity measures. Nine years later, our brethren in the Central Security Forces rose in one massive uprising against the draconian conditions of their conscription. Fourteen years later, in 2000, we took to the streets in large numbers protesting against the Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s visit to Jerusalem’s al-Haram al-Sharif, the third holiest site in Islam.

Thus we are back full-circle to the immediate causes of the revolution of 25 January 2011.

On that day, I went to Tahrir Square to join what I thought would be yet another small demonstration, doomed to be crushed by overwhelming police force. The minute I stepped in, however, I realised that this time the situation was different. Our numbers were huge. The slogans were new. There was the same beat as familiar slogans, but now I heard strange, unrecognisable words. Soon, I figured out what people were shouting: ‘Al-sha‘b.’ Stop. ‘Yurid.’ Stop. ‘Isqat al-Nizam.’ Stop. ‘The people.’ ‘Demand.’ ‘The downfall of the regime.’ Goosebumps spread all over my body. I then found myself joining tens of thousands of fellow citizens at the top of my voice.

For the following 18 days, I went to Tahrir nearly every day, returning home only to sleep and get provisions for my friends who preferred to camp in the square. Mubarak’s step-down was only a matter of time, we firmly believed: the regime is teetering on the brink of collapse; we are finally making our voice heard; we are shaping our country’s future. And soon a new slogan spread like wildfire throughout the huge midan and was repeated by hundreds of thousands of people from all walks of life: ‘Irfa‘ rasak fo’. Inta Masri.’ ‘Lift up your head. You’re Egyptian’.

Three and a half years later, this confident, hopeful mood is no more. Instead of the open, democratic country that seemed, for a short while, to be ours at last, Egypt is now in the grip of a military dictatorship that has arrested our friends, imprisoned our comrades and quashed our dreams. Kangaroo trials have passed death sentences on hundreds of Islamists in sessions lasting less than an hour. And on 14 August 2013, security forces committed what Human Rights Watch described as one of the world’s largest killings of demonstrators on a single day in recent history, a massacre in Raba’a Square in Cairo that was more lethal than Tiananmen Square and which probably amounts to a crime against humanity.

How did the 18 days in Tahrir that saw so many Egyptians embracing these lofty ideals lead to 12 hours in Raba’a Square that witnessed a massacre in which more than 800 people were killed? How did we start in such hope in 2011 and end up with this bloodbath in 2013? How did the Arab spring morph into an Arab nightmare, out of which we seem not able to awaken?

Far from being a Facebook phenomenon, a foreign conspiracy, or an insurrection staged by a handful of street urchins – as members of the current Egyptian regime in their phantasmagorical delusions insist – the Egyptian revolution has a long and venerable pedigree. We, the people, have been in a state of constant rebellion for the past 200 years, and 25 January 2011 was but the latest phase of a long struggle to force the tyrannical state to serve its citizens, instead of us serving it.

Why has it proven so difficult for Egyptians to end our status as subjects in our own country and to force our state to treat us as citizens?

Five reasons stood, and still stand, in the way of democracy in Egypt and indeed in the whole of the Arab world.

First, despite their deafening rhetoric, Western powers have not spared an effort to thwart our struggle for democracy. As noted above, the British not only crushed our first constitutional movement in 1881-82, but also handicapped our second attempt when they intervened in the writing of the 1923 Constitution to tip the balance in favour of their pliant client king and against the nascent parliament. Britain’s moment in the Middle East came to an end, of course, and the US has taken over as the global superpower. Washington, DC has not missed an opportunity to support Egyptian dictators over the Egyptian people, just as it has in neighbouring countries.

Second, the century-long Arab-Israeli conflict has sapped our energy and diverted precious resources. But more insidiously, our own despots have used it cynically to postpone democratic reforms indefinitely. The slogan ‘No call to top the call for battle’ has been deployed domestically to silence all calls for democracy and reform. Moreover, our struggle with Israel necessitated the expansion of the military. When this military failed in its mission at the borders, it diverted its energies to the domestic sphere, transforming itself into a mighty economic and political player that rightly saw democracy as inimical to its interest.

Third, the scourge of petro-dollars has meant that the oil-rich and despotic regimes of the Gulf could interfere in Egypt and support anti-democratic forces. The success of the counter-revolution following 30 June 2013 could not be understood without taking into account the billions of dollars that both Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates paid the new Egyptian regime. This heavy support from the Gulf states to the counter-revolutionary regime stems from their realisation that the Egyptian revolution could have a domino effect in the region. If allowed to succeed, it could shake the despotic foundations of these Gulf states.

we in Egypt, Libya and Syria found that we had opened the Pandora’s box of political Islam

Fourth, the tragedy of Egypt’s current revolution also lies in our inability to look back to our modern history and choose a moment that we would like to resurrect or emulate. There is no ‘reset button’ that we can press to jumpstart our history; no one specific dark moment that we can simply wish away; no isolated anomalous period that we would like to suppress; no imagined golden age in which we can claim we shaped our destiny and to which we want to return. In this, Egypt is not unique. The history of postcolonial states has seen few victories of democracy and justice.

Finally, and to make things even more difficult, in attempting to tame the domestic Leviathan, we in Egypt, Libya and Syria found that we had unleashed the forces of political Islam. For our revolution posed not only the question of what ought to be the role of the army in society but also what role religion should play in politics. This matter opened up existential questions with which Egyptians and Arabs have been struggling for more than a century.

It is also true that the new regime has taken repressive measures against the Egyptian people, moving to push us back into history’s antechamber. Despite these deep problems, I remain confident that the future is ours and that our revolution will prevail. This might not happen next month, next year, or even in the next decade. Given how deep are the roots of, and reasons for, this revolution, it would be naïve to expect its victory overnight with one decisive, knockout blow. Despite the challenges, I am convinced that we are now witnessing the beginning of the end of the tyrannical Egyptian state.

My optimism derives from two simple but profound facts. The first is that the Egyptian people have asserted our presence in our own country. We have a will; we have a voice; and we have agency. In 2011, like in 1919, we made history and brought radical change. Never before in our long history, extending back to the pharaohs, did we manage to topple a leader from power. In the January revolution, the Egyptian people did just that. We asserted our right and determination to shape our own destiny.

We have opened the black box of politics. Politics is no longer what government officials, security agents or army officers decide among themselves. It is no longer what university students demonstrate about, what workers in their factories struggle with, or young men in mosques whisper over. Politics is now the stuff of coffee‑shop gossip, of housewives’ chats, of metro conversations, even of pillow talk. People now see the political in the daily and the quotidian. The genie is out of the bottle and no amount of repression can force it back in.