Shortly after midnight on Friday, 28 January 2011, someone in 26 Ramses Street, a nondescript 12-storey office building in downtown Cairo, turned off Egypt’s internet. No email, web access, WhatsApp or Skype. It didn’t matter. A few hours later, Egyptians came out and made a revolution anyway.

Tahrir Square, the physical epicentre of that revolution, was many things: a performance, a myth, an arena of battle and an alternative story. But above all, it was a response to a society in which individual stakes in the status quo had become exceptionally unequal. As a result, it sought to provide an antidote to that inequality, with messy, mixed results. In Tahrir, emeritus professors rubbed shoulders with street vendors and steel workers; Salafists set up tents next to Marxist hipsters. The square cost nothing to enter, and its inhabitants policed it collectively on their own terms. It was a far cry from the Egypt beyond its borders, vast swathes of which had long been sealed off, commodified and guarded in the interests of private gain.

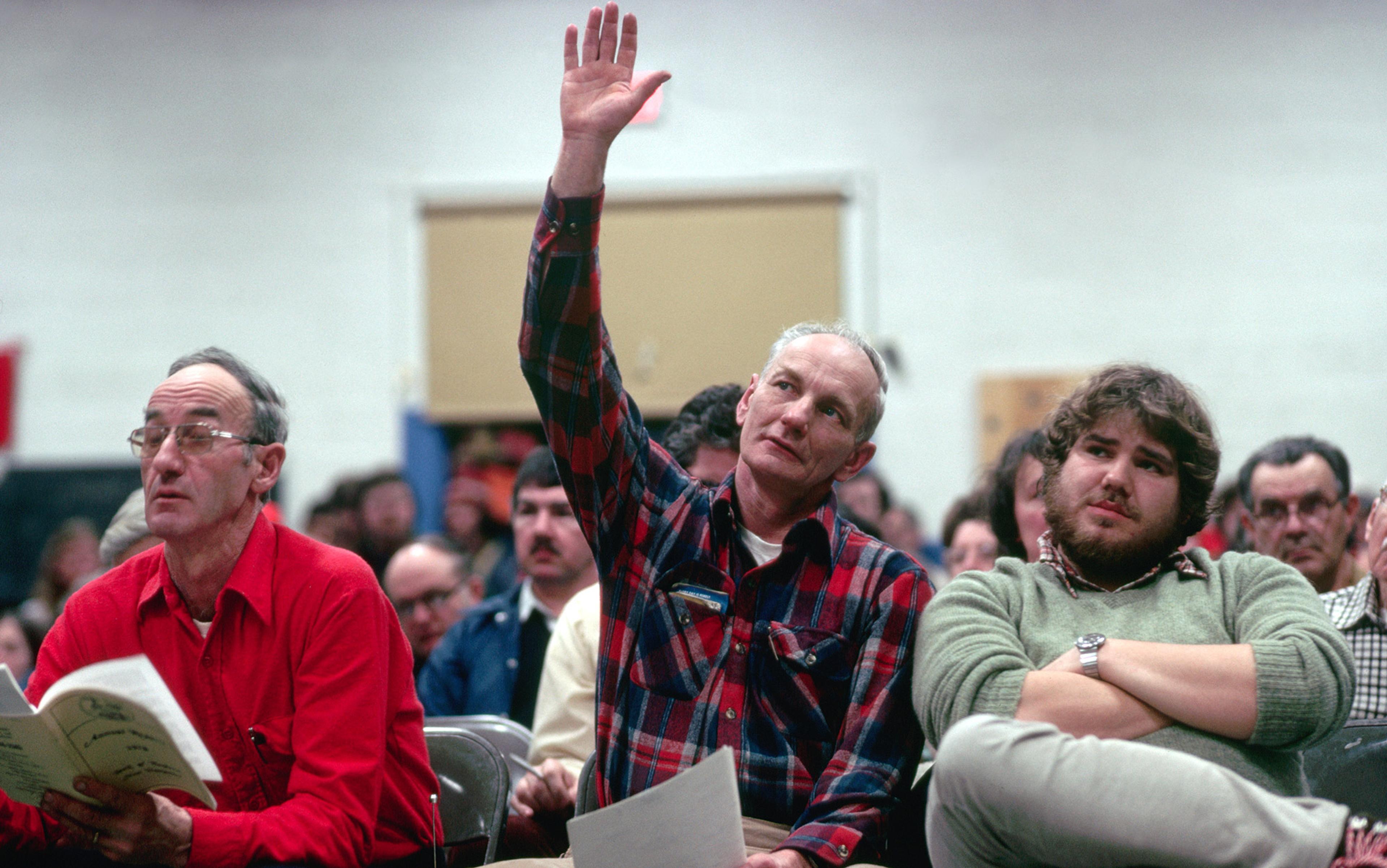

At its best, Tahrir was the quintessential public space, and contained echoes of the commons: the open land that once dominated much of early modern Europe, particularly in England, to which most members of the community could claim equal rights. ‘El-shari’ lina,’ protestors in Egypt chanted. ‘The streets are ours.’

As a rising tide of popular sovereignty on the Nile swept away Egypt’s dictator Hosni Mubarak, an odd consensus swiftly developed among many academics, tech entrepreneurs and members of the ancien régime itself. It was that digital technologies had played a defining role in what happened, particularly the giant social media platforms that often style themselves as today’s global commons: supposed enablers of unmediated access to a shared social good that all can enjoy without fear or favour. The aim of Google, according to its parent company Alphabet, is ‘to organise the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful’; Facebook’s mission statement is to ‘give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together’.

To the terrified old guard of Egyptian politics, that sort of language was unwelcome; the humming grid of infinitely interconnected nodes and data lines that ran through the national telecoms exchange at 26 Ramses Street had never seemed more tangible, solid or dangerous. Yet their diagnosis was wrong. It’s true that online communication played a critical component in the Egyptian revolution. But a manifestation was being mistaken for a cause.

On that January afternoon, I stood on top of an overpass in Giza watching bands of kids zigzagging through mounds of rubble. In one hand, they carried tubs of paint to hurl onto the windscreens of armoured security trucks, blinding their drivers; with the other, they threw rocks at the policemen who arose with guns from hatches in the vehicles’ roofs. Throughout the preceding weeks, many of these young rebels had utilised Facebook groups and Twitter threads to find one another, plot illicit rallies, and outwit the authorities. Now, unable to Tweet or post, they nonetheless had debris to navigate and a world to win.

To interrogate the part played by digital technologies in unleashing these kids and upending Egypt’s existing model of power, and to understand why hitting the internet ‘off’ switch failed to save it, one had to explore the underlying conditions that enabled such technologies to have any political impact in the first place. Mubarak, and those such as David Talbot at MIT Technology Review who in 2011 heralded the world’s first ‘Facebook revolution’, had it all the wrong way round.

Today, on a wider canvas, many are continuing to make that same category error. Digital technologies are changing politics as we know it, but not because of some inherent or immutable characteristic that stands apart from the world in which they were created. Instead, these technologies have helped an underlying condition, namely growing discontent at marketisation – the privatising of ever more goods, services and social interactions, and the ideologies that justify that process – to find meaningful expression in the formal political arena. The result has been successive electoral shockwaves that have shattered long-held certainties and splintered the political spectrum.

Ironically, digital technologies are capable of playing this role precisely because in reality their own development and logic owes so much to market forces. Behind the advertising copy, Apple, Amazon and the other tech giants share far more with the Enclosure Acts of the Tudor period than they do with the common land those acts so violently eroded. Facebook, Twitter and co are simultaneously creatures of a neoliberal orthodoxy and engines of its crisis. But contained within this irony is a kernel of hope: not only that such technologies are not necessarily antithetical to the sort of politics we should be fighting for – a sort that places the ideals of Tahrir above those of the Egypt it stood against – but also that they could yet play a vital role in rejuvenating them.

The internet is so potent, we are often told, that it could threaten the very notion of liberal democracy as we know it. Maybe so. But its real potency lies in the fact that this forces confrontation with a deeper question altogether: whose democracy, exactly, is currently being imperilled?

When the dust (somewhat) settles, and distant generations of undergraduates are charged with reeling off explanations for the churning politics of our age, the contribution made by digital technologies will rightly occupy a bullet point or two on the essay plan. From Brexit to Donald Trump, from Michel Temer in Brazil to Narendra Modi in India, democratic ruptures – not so much of the formal mechanisms or even institutional conventions of liberal democratic systems, but more importantly of the social languages that gird them – can certainly be traced in part back to the transformations wrought by the web. Large sections of the media have gone from mainstream to legacy, and the mushrooming of personalised, confirmation bias-driven newsfeeds have fragmented the public conversation, which in turn has limited our exposure to alternative perspectives, and altered our conception of ourselves. Around the world, an assumed infrastructure of broadly shared values has been exposed as precarious at best, and illusory at worst.

Digital technologies are not the core generators of this process, but nor are they merely a camera impassively recording the fallout. As well as encouraging transnational connections, our online identities – channelled through the walled gardens of social media platforms or the user-specific algorithms of search engines – have in many cases fuelled a retreat into echo chambers, and it is authoritarian populists who have been best placed to capitalise. At the core of any demagogue’s appeal lies a claimed moral monopoly on representation; they, and they alone, speak on behalf of the silent majority, while other political actors are illegitimate. So it was that Trump announced that ‘Crooked Hillary’ would be locked up under his administration, and Nigel Farage hailed an EU referendum victory for ‘real’ people.

Such characters have always circled the fringes of democratic systems. But now digital technologies create microclimates that can accommodate physically scattered millions, in which grievances are amplified and authoritarians can offer a fantasy of liberation from them without intermediaries. Belief in the existence of widespread voter fraud hardens when every news item appears to confirm it; do a web search for one racist theory and your future web searches will see pages with racist content soar up the rankings. From inside the morass, benevolent strongmen appear to offer a two-way transmission line between aggrieved subjects and organs of power. As the political scientist Jan-Werner Mueller pointed out in the London Review of Books in 2016, anti-democratic figureheads invariably promise a facsimile of direct democracy while in reality cleaving to a strongly representative model – one in which they, uniquely, are the genuine representatives.

But sweeping claims regarding technology’s potential to transform the political basis of societies, whether for better or for worse, are nothing new. Indeed, in Egypt, they are as old as the pyramids. Pharaonic-era priests derived their legitimacy in part because of their seemingly divine ability to predict the rise and fall of the river’s floods, which determined the entire kingdom’s prosperity. In fact, they relied on Nilometers installed in the cellars of religious temples, which recorded the changing water levels; centuries of accumulated data made accurate forecasting relatively easy. As Nilometers eventually passed into the hands of state officials, the priesthood feared that their elevated class status would diminish, just as European scribes did upon the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. Gunpowder was credited with democratising warfare in the Western world; in China, it served to reinforce feudal hierarchies. In each instance, new technologies served to accelerate or materialise existing social and political dynamics, not conjure them out of the ether.

Digital technologies have encouraged a retreat to ‘imagined communities’ where the consensus is decried

History’s lesson is that no technology is static, and we should not be fatalistic about its influence. New technologies create both hazards and opportunities – sometimes within existing political frameworks, at other times by reshaping those frameworks altogether – but the actualisation of those hazards and opportunities depends entirely on human agency. ‘Technology does not drive anything,’ argued Rakesh Rajani, the Tanzanian civil society leader, in Foreign Policy in 2015. ‘It creates new possibilities for collecting and analysing data, mashing ideas and reaching people, but people still need to be moved to engage and find practical pathways to act.’

The issue then, is not that contemporary technologies are innately undemocratic; it is why, under current circumstances, they are having a deleterious effect on democracy, and under what future conditions this effect could be altered. The answer lies in the fact that we are living through a moment of flux, one in which an old order is breaking down but a new one has not yet formed. An economic unravelling that began with the crisis of 2008, and that has already disarrayed the political status quo in many areas of the planet, is finally taking its toll on institutional governance in some of the world’s oldest democracies, including the United States. For citizens locked out of the headline successes of a highly financialised, globalised and GDP growth-orientated system, discontent has been mounting for years: against the mainstream political accord surrounding the desirability of marketisation (including by the social-democratic parties of the liberal Left), and against the data-driven expertise used to justify that accord – which often appears to contradict the reality of lived experience. In an era of growing corporate power that transcends state boundaries, established political actors appear complicit in the disconnect – and, worse still, impotent.

Against this backdrop, digital technologies have encouraged a retreat to so-called imagined communities where the consensus is decried and a backlash against liberalism – not just its economic form, but its social character, too – has gathered pace. What some describe as an assault on democracy, others see as the triumphal return of politics after decades of staid, and often savage, technocracy. Fake news is now in vogue. But from weapons of mass destruction in Iraq to the insistence that secure employment is now an anachronism in post-industrial regions, for large numbers of citizens in august democracies it has been only too familiar for years. Faith in supranational polities has been an early victim of the recoil. We were once told that the internet would transcend the nation state, and that it was easier to picture the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Today, nostalgic nativism is on the rise, and it feels easier to picture the end of capitalism than the end of the nation state.

And herein lies the paradox. Despite their pretensions to the contrary, digital technologies, in their current guise, are a product of the very free-market fundamentalism – the very politics – that many voters are reacting against. There is nothing impartial, or natural, about the way that Facebook and its counterparts have evolved: they are an outcome of privatised imperatives. The billions of lines of code that increasingly colonise our private worlds and public spaces are wrapped in a veneer of neutrality, but they are neutral only in the sense that they lead us dumbly down whichever roads will generate income for their owners. That drive for income places digital technologies within an ideological framework which is itself deeply biased. As the former quantitative trader Cathy O’Neil puts it in Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (2016): ‘There’s always a measure of success for any algorithm, and the general rule is that if you don’t know what that is, it’s probably profit.’

It is the pursuit of this particular measure of success that has given us the digital universe we inhabit today. In order to maximise marketing revenue, public-facing elements are ruled by click-counters. Meanwhile, the backend of digital systems, which collate and commodify data points to sell to the highest bidder – be that marketers, security screeners or political campaign operatives – exists beyond the searchlight of democratic scrutiny, with all the problematic inequalities, intrusions and exclusions that entails.

There is no reason why our digital infrastructure has to operate in this way, and every reason to recalibrate it so that it functions differently. Today, as citizens, the streets we walk down and the squares we gather in are as much virtual as they are physical. In strings of ones and zeros we meet one another, socially filter our fellow beings, discover the world beyond ourselves, and thrash out dreams of our future; it is increasingly through our digital information systems that we organise and imagine our collective existence.

As new forms of automation and artificial intelligence technologies go on to harness our data and transform every aspect of the world around us – from our transport networks to our healthcare – the question of how we conceptualise these digital systems, and whether we understand our own role in them to be primarily those of citizens or consumers, will grow only more acute. We rightly view with alarm the old company-towns of the US rustbelt or northern England, designed and dictated entirely by coal barons or other industrial magnates for their own purposes. Yet to date we have acquiesced in the construction of a far larger digital metropolis in which the notion of public accountability is assumed, almost by default, to be inapplicable.

So it is that we have arrived at a point where Apple has the chutzpah to announce the rebranding of its retail outlets as ‘town squares’. As a 2017 headline in HuffPost summarising Stephen Hawking’s views on this subject put it succinctly: ‘We Should Really Be Scared Of Capitalism, Not Robots’. More perceptive future undergraduate students might use their essays to chastise our own generation for so passively accepting the enclosure of our digital commons as the long 20th century drew chaotically to a close. The scary thing is how unremarkable that choice felt; its very mundanity rendered it almost invisible.

Do we still believe in the socialised creation and exchange of knowledge?

To wind up there, however, would be an abdication of our shared potential to generate alternatives. In this interregnum between the old world and the new, our struggle must be to find new ways to harness digital technologies to a stronger, more robust and inclusionary democracy: one that relies neither on thin forms of representation nor the false comforts of rule-by-plebiscite. To do so we must think big – which means going beyond questions about the way we vote, or how we regulate AI insurance brokers, beyond even tensions over data openness or individual online privacy. Digital technologies will help to make a more democratic politics possible when we build new public digital infrastructures that are owned in common and geared towards social goods. To do that, we must force a political conversation in which such ambitions do not appear unrealistic.

It is already happening. Wikis, open-source software and the Creative Commons copyright licence are all digital commons in their own right; initiatives such as Turkopticon, which ‘hacks’ Amazon’s Mechanical Turk marketplace for crowdsourced labour to provide workers with better information and more power when navigating potential employers, illustrate how common endeavours can disrupt privatised digital infrastructure from within. At the local level too, examples abound: the Beijing residents collecting air-quality data from the ground up, the tax-justice campaigners crowdsourcing their investigations into high-end financial improprieties, the reporters who use digital tools to collaborate on maps of migrant routes across the Mediterranean so that more stories can be told, and more lives, sometimes, can be saved.

The fight to scale up such initiatives and reimagine what our digital universe could look like involves enabling democratic deliberation around the creation of digital data, as well as the ways in which it has come to structure our lives. This is not simply a battle over whether elites can succeed in foisting unpopular facts upon a populace now stubbornly wedded to a post-truth politics of feeling. It is about whether we still believe in the socialised creation and exchange of knowledge, and about the arguments we must have with those who profit from the ongoing disintegration of these things. It is a fight that speaks directly to the political moment we are staggering through. It is a fight that is winnable, and urgent.

The shadowy men who gazed at that beige, nondescript office block in Cairo and thought that they could switch off the insurgency erred because they assumed a particular type of politics lay locked within its tubes. The truth was that digital technologies were as relevant as those on the ground, fighting for a different vision of politics, wanted them to be. Last year, the latest iteration of Egypt’s dictatorship drafted a new cybercrime law that would make the illegitimate trading of ideas online an offence, punishable by up to 15 years in jail – evidence that, in the traumatised minds of Egypt’s oppressive government at least, the association between democratisation and the digital world remains very much alive.

That such an absurd piece of legislation could even be considered necessary is grounds for optimism and not despondency. ‘The future is dark,’ wrote Rebecca Solnit in Hope in the Dark (2005), ‘with a darkness as much of the womb as of the grave.’ Which is another way of saying that when thinking about the relationship between digital technologies and politics, we belong not with the shadowy men at 26 Ramses Street but with the kids up on the overpass zigzagging through the rubble – throwing rocks, opening spaces, forging possibilities.