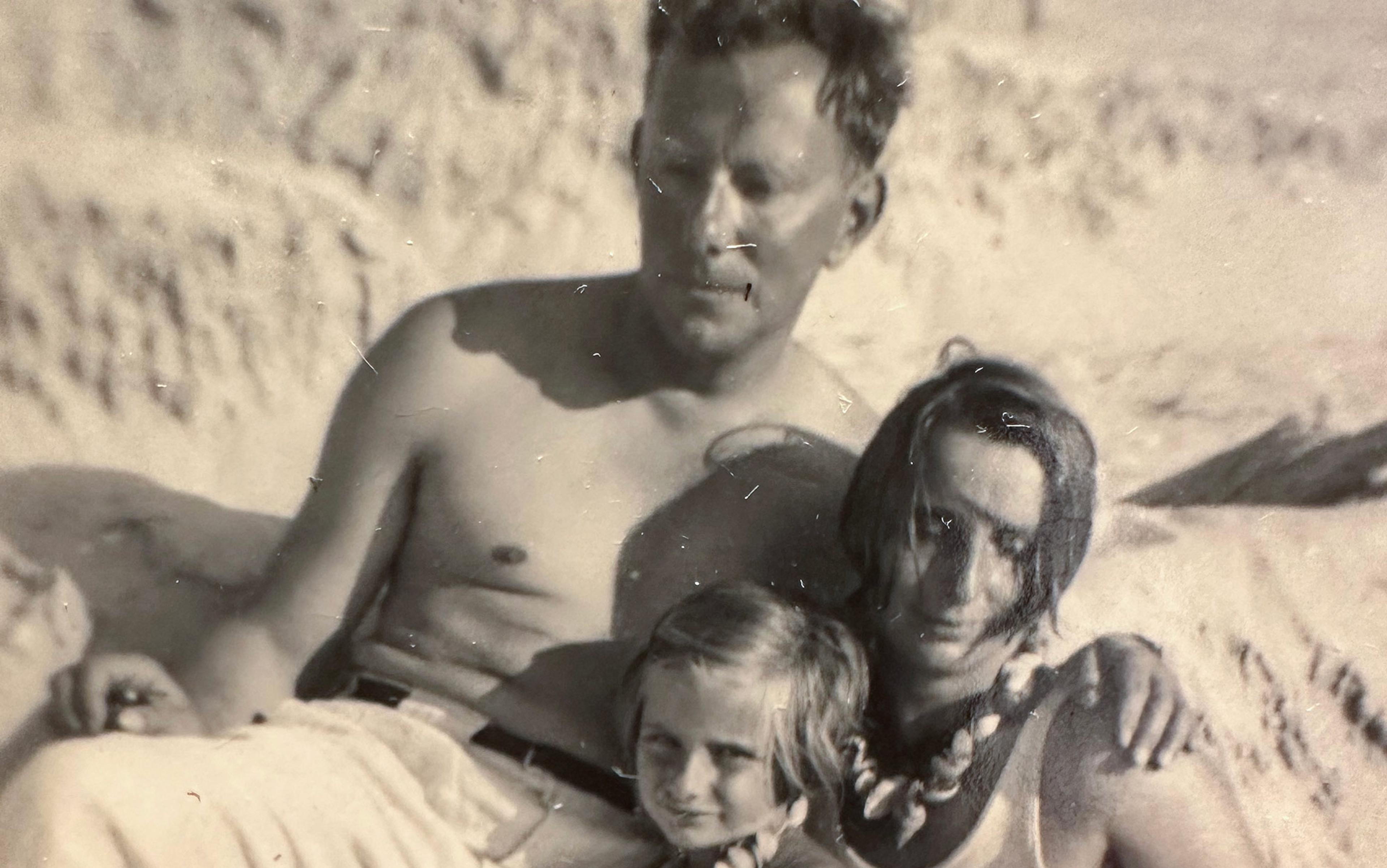

My recollections of my grandfather are mostly from childhood visits to my grandparents’ summer cottage in East Hampton in the 1950s and ’60s. The village, with its magnificent Atlantic beaches on the South Shore of Long Island, had already become an intellectual and artistic summer gathering place for European academics, writers and artists displaced by the Second World War. And my grandfather, who had an active social life, counted many of them as friends.

My grandmother, Hannah (or ‘Oma’ as we called her), made it very clear that her husband’s sacred time for writing from 8am to 11am was inviolable, and she protected him from the noise and childish distractions my younger sister and I provided. In the evenings, he would preside over dinner or cocktail parties for friends and acquaintances from the academic and artistic community of what is now called the Hamptons. Occasionally, my grandfather would engage me in a game of chess that, inexplicably, I always lost. I never had the chance to discuss philosophy with him as he died when I was 13, but the conversation at dinner in the Tillich household was rich with ideas, political events and the work of writers and artists I would learn about only much later.

Tillich had been among the first group of professors and the first non-Jewish professor to be dismissed by Hitler for opposing Nazism. The Nazis suppressed his book The Socialist Decision (1933), and consigned it to the flames in Nazi book burnings. In late 1933, he fled Germany with his family to the United States, where he became established as a public intellectual, holding positions as professor of philosophy at Union Theological Seminary in New York and then as a university professor at Harvard, and finally as professor of theology at the University of Chicago Divinity School. During the Second World War, Tillich made radio broadcasts against the Nazi regime for the US State Department and assisted European intellectuals in emigrating to the US. In the 1940s, he served as chairman of the Council for a Democratic Germany. Due to the interest of the magazine magnate Henry Luce and his wife Clare Boothe Luce, Tillich was featured on the cover of Time magazine in March 1959 and was the featured speaker at Time’s star-studded 40th anniversary gala dinner.

Paul Tillich was raised in the 19th century to conservative parents in a walled medieval village in Brandenburg, Germany. His father was a Lutheran pastor and Church administrator, born and educated in Berlin. His strict parents tried to imbue the young Paul with traditional religious values. They failed.

Tillich lived through great social, political and technological change driven by two world wars, the wild freedom of the Weimar Republic and the fateful beginnings of the Nazi regime. After fleeing to the US, he lived through the Second World War, the McCarthy era, and then the beginnings of the American Civil Rights Movement, student unrest and the emergence of psychedelic drugs. Turning down an opportunity from Timothy Leary and his own assistant, Paul Lee, to try LSD while at Harvard, Tillich told them he was from the wrong era for such experimentation.

He considered himself a boundary thinker between philosophy and theology, the Old World and the New

During the First World War, Tillich was awarded the Iron Cross for courage and military contributions in battle, after surviving a four-year stint as a chaplain in the German army. His traumatic experiences at Verdun and elsewhere on the Western Front led to two nervous breakdowns. These experiences along with his postwar life in Weimar Berlin, his open marriage with Hannah Tillich, and his political and philosophical engagements with socialist academic colleagues, artists and writers shattered the 19th-century worldview and traditional religious conceptions of God and faith taught by his conservative parents and drove him to redefine his philosophical outlook.

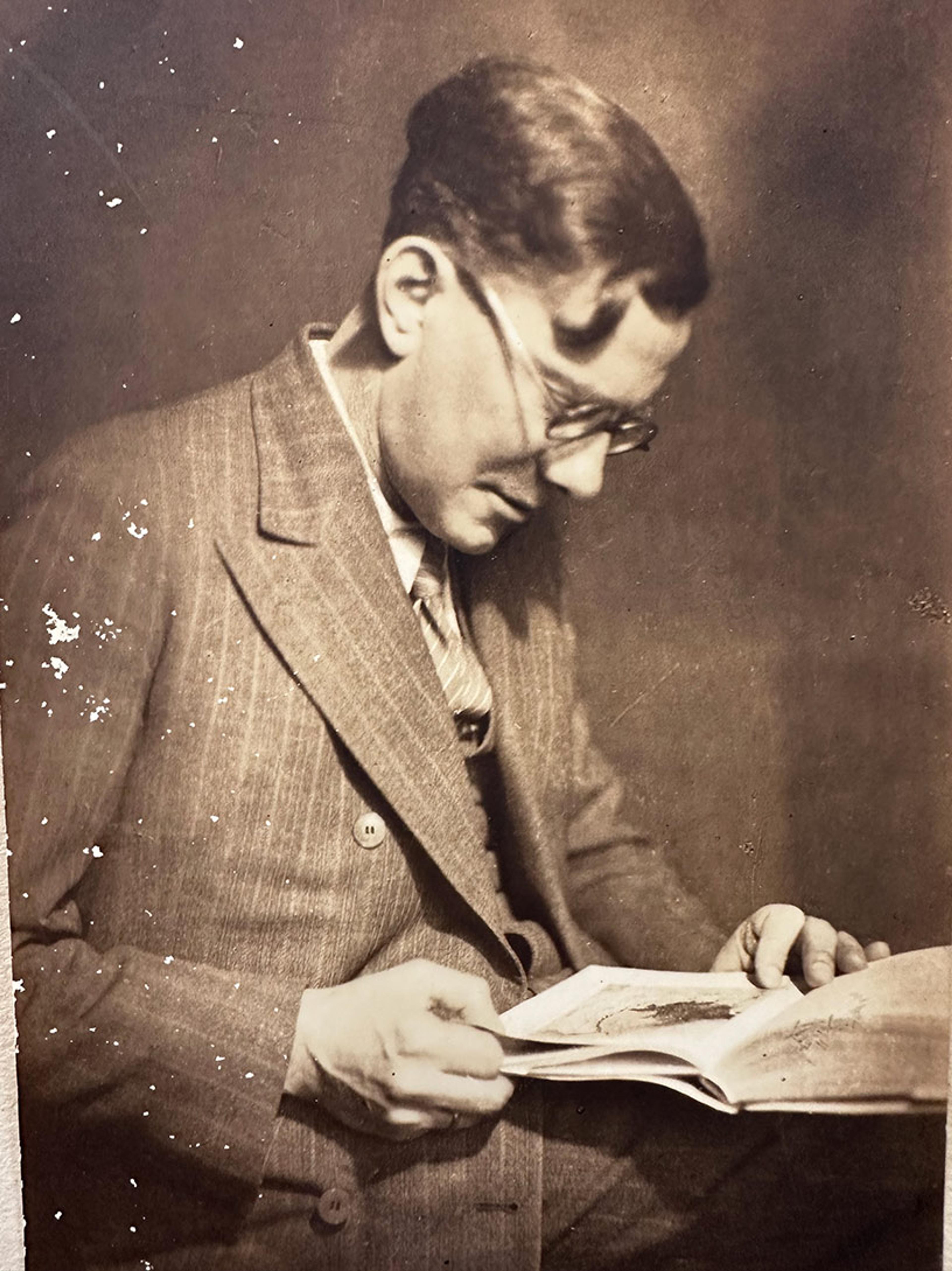

Paul Tillich in 1933 in Berlin.

While actively participating in intellectual circles, Tillich cultivated friendships with other key thinkers. As a philosophy professor at the University of Frankfurt, he helped establish a chair in philosophy to bring Max Horkheimer to the faculty. He also supervised Theodor Adorno’s doctoral dissertation (habilitation thesis). While not formally affiliated with Horkheimer and Adorno’s neo-Marxist Institute for Social Research, Tillich maintained lifelong relationships with both men. Other friends and acquaintances included Mircea Eliade, Erich Fromm, Adolph Lowe, Hannah Arendt, J Robert Oppenheimer, Erik Erikson, Karen Horney and Rollo May.

Tillich considered himself a boundary thinker between philosophy and theology, religion and culture, the Old World and the New. His lectures ranged far beyond the usual theological ones, and included secular topics such as art, culture, psychoanalysis and sociology. His interdisciplinary thinking encompassed the enormous social, political, technological and intellectual change and conflict through which he lived. He didn’t easily fit within existing categories.

In the 1920s and ’30s, while still in Germany, Tillich regarded himself as a ‘religious socialist’ and a strong opponent of Nazism. Written in 1932, his book The Socialist Decision provided an alternative vision to the extremes of the nationalist Right and the communist Left that were tearing his homeland apart. He envisioned a unified harmonious socialist community inspired by Christian ideals, justice and political equality, believing, somewhat naively, that the collapse of the Weimar Republic could be a ‘Kairos’ moment (the ‘right time’ for a historic change) that might provide an opportunity for this breakthrough.

According to Tillich, nationalist authoritarianism relies on the origin myth of a culturally and racially pure society in some idealised, romanticised past, a description that encapsulates many modern populist movements. Tillich’s religious socialism combined Christianity with politics and culture, offering a Leftist humanistic conception of Christian teachings. This was his attempt to unite Christian and Social Democratic ideas against Nazism and its myths of origin, blood and soil. Tillich wrote presciently that:

If … political romanticism and, with it, militant nationalism proves victorious, a self-annihilating struggle of the European peoples is inevitable. The salvation of European society from a return to barbarism lies in the hands of socialism.

By the time the book appeared in 1933, the Nazis had already seized power and were rapidly eliminating all opposition. Tillich’s attempt not only failed but made him a target. The Nazis reviled The Socialist Decision and suppressed it soon after publication. Tillich was lucky to escape Germany. Once when the Gestapo knocked on the door looking for him, his wife informed them that he was away. (He was actually out for a walk.)

In April 1933, Hitler’s government suspended Tillich from his Frankfurt University professorship. The dismissal stunned Tillich and he was slow to react, not managing to leave Germany until late October 1933. He even appealed his dismissal to the German Ministry of Culture after he arrived in New York. The appeal was curtly rejected.

His Frankfurt colleagues Horkheimer and Adorno were also to leave Germany within a year. At Reinhold Niebuhr’s invitation, Tillich joined the faculty of Union Theological Seminary, where he became a professor of philosophical theology at the age of 47. While he initially struggled to learn English, he gradually developed into a charismatic and sought-after lecturer.

Defying the traditional notion of a theologian, Tillich worked across the fields of philosophy, theology and culture, focusing on the personal search for answers to ultimate questions. He examined the human quest for meaning, but without theorising about the nature of God. God, he thought, could be discussed only symbolically and never literally.

His thought was founded on the conception of humans as finite and separate individual mortal beings. While limited by their finitude, humans are always searching for meaning, purpose and justification, concepts that refer to the infinite Universe beyond themselves. As finite beings, humans can never reach or grasp the infinite, but remain deeply concerned with and driven by the ultimate questions of meaning and purpose in their lives.

In understanding Tillich’s theology, it is important to begin with his two key concepts: faith and God. Tillich considered faith not a belief in the unbelievable, but the ‘state of being grasped by an ultimate concern’; and he conceived of God not as a being, but as ‘the ground of being’. Both concepts are consistent with secular humanist as well as religious conceptions of the Universe.

The ‘ground of being’ could mean the Big Bang, the Universe itself or a universal God

Tillich’s thought fused religious and secular ideas of morality by refusing any fixed moral ideology and by rejecting traditional notions of an authoritarian, top-down ‘God rules Man’ and ‘Man serves God’ religious approach. He conceived of love and justice as the unifying social forces in the face of the fundamental anxiety created by human mortality and separateness. For Tillich, religion, morality and meaning come from humans, not from God. He focused on the experience and feelings of upward-looking humans searching for meaning rather than on a religious superstructure of a downward-looking God. This is as much a psychological approach as a religious one. Tillich’s approach promotes acceptance of our humanness, our mortality, our finite being, and of the differing ideas, meanings and morals that we each develop for ourselves. His openness to the existential uncertainty confronting all people in considering questions of ultimate importance was rare in theological circles during his lifetime.

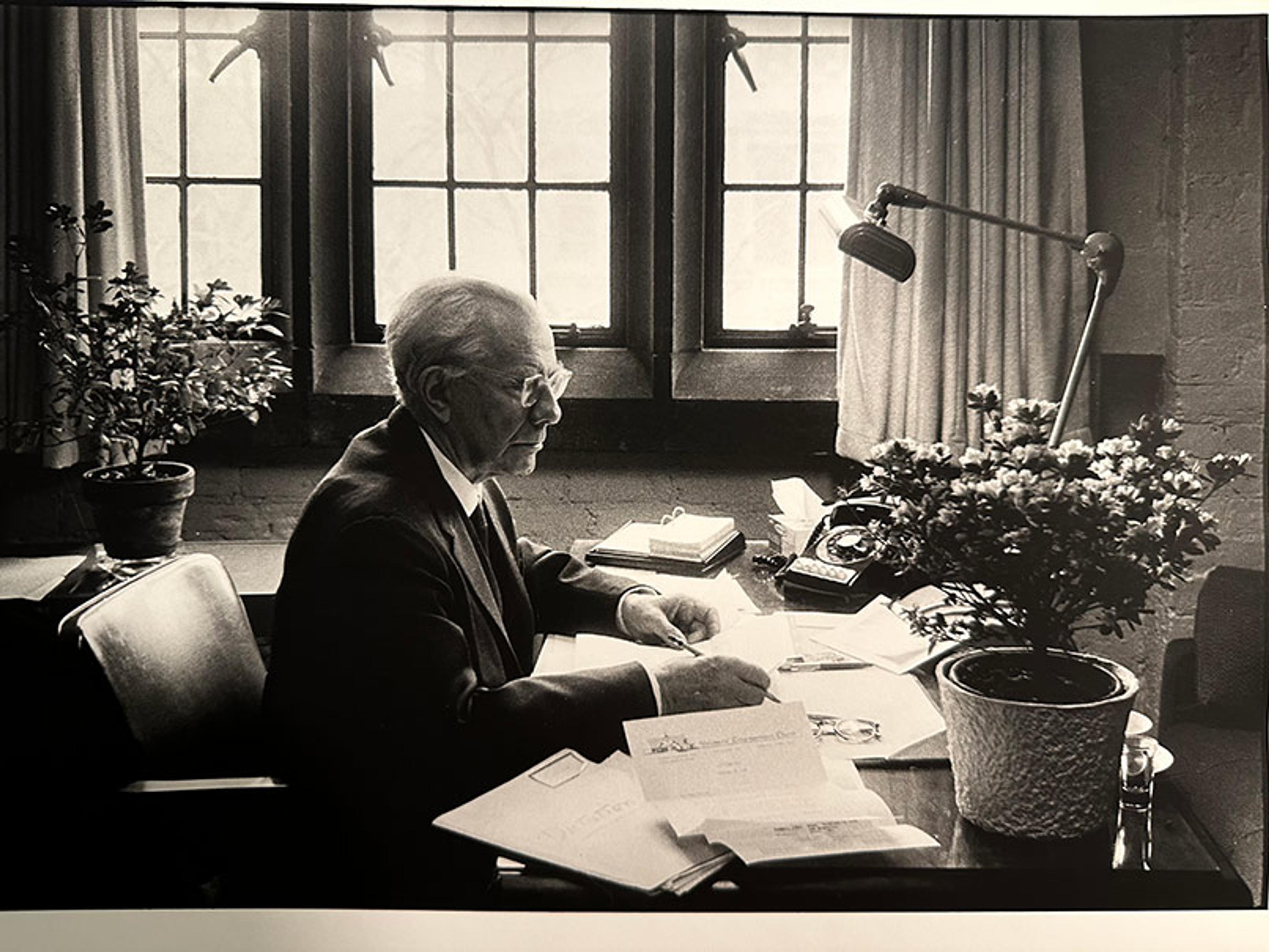

Paul Tillich at his desk in Harvard c1955

His key philosophical terms recast nominally religious elements in a manner that expands their relevance beyond Christianity. Tillich’s radical approach to faith as an expression of ‘ultimate concern’ eliminates the importance of narrow denominational religious orthodoxies. His idea of God as not a being, but the ‘ground of being’ and Man as a finite being, means that God is beyond the intellectual grasp of humans, and religious statements about the nature of God can never be taken literally. This broad conception brings together religious faith and secular and scientific concerns regarding the origin of Man and the Universe. For Tillich, the ‘ground of being’ could mean the Big Bang, the Universe itself or a universal God. He rejected the traditional theistic notion of God as a being that moves around the Universe doing great things and worrying about, interfering with and scolding human beings. Rather, Tillich conceived of God as a symbolic object of the universal human concern for ultimate questions of meaning and purpose. God is thus outside our Universe and is a symbol for the answers to our deepest questions, but the answers always elude our grasp.

One of the most difficult aspects of Tillich’s thought is the ambiguity that characterises much of his writing. Among the most puzzling and paradoxical ideas in his Systematic Theology (1951) is his statement that ‘God does not exist’ and that ‘to argue that God exists is to deny him.’ Tillich goes on to state that the word ‘existence’ should never be used in conjunction with the word ‘God’. These assertions fit with the idea of God as a symbolic object that is a repository of ultimate concern, but not a being. Tillich scholars have disagreed on the meaning and significance of these passages. Does Tillich mean that, since God is ‘beyond essence and existence’ and exists outside of time and space, God is not part of existence? Or is Tillich implying that God really doesn’t exist and is not required to do anything in the Universe? Certainly, in Tillich’s theology, God is an abstract and somewhat inactive concept. The action all comes from the human side through faith. God is the unreachable object of our ultimate concern. This illustrates some of the difficulties of interpreting Tillich’s intentionally paradoxical and deliberately ambiguous assertions as he tries to avoid discussing the literal nature of God.

Tillich describes faith as an ecstatic ‘centred act of the whole personality’, but insists that faith always includes doubt and can include demonic or idolatrous elements that are not ultimate concerns. He wrote that uncertainty is inherent in faith (and apparently sometimes in reading Tillich), and that human courage is essential to overcoming the risks of the unavoidable uncertainty and doubt regarding our ultimate concern, ‘be it nation, success, a god, or the God of the Bible.’ The risk of this uncertainty is a loss of faith that breaks down the meaning of one’s life. This loss of faith has happened many times with the collapse of utopian ideologies, states and empires from those of communism and fascism, to monarchies and failed democracies.

The point here is simple. As humans, we share many varied belief systems, any of which may be false or may ultimately collapse, evolve or disappear entirely. This is the risk of faith. Yet humans cannot live without it. We always have faith, whether or not we acknowledge it, because we always have ultimate concerns. Faith is a response to the finiteness of human existence. Our faith in ultimate meaning takes us beyond our finitude to something infinite that might answer ultimate questions of meaning and purpose, yet answers always lie beyond our grasp. Tillich’s humanistic and existentialist theology analysed the path of each person in their individual struggle with and community approach to faith and God. And Tillich was above all else a humanist, although he recognised that liberal humanism was also a secular quasi-religion.

Faith based on utopian or populist political ideals could become an idolatrous quasi-religion

This radical redefinition of faith as a concern for ultimate questions broadened the meaning of faith beyond religion to the universally shared human effort to address spiritual, social, political and aesthetic concerns – humanity’s search for meaning. He recognised that any belief system could be a source of ultimate or at least ‘preliminary’ concern. For example, faith in extreme nationalism risks turning the nation itself into an authoritarian god. But nationalism was a false, idolatrous and demonic god. Tillich, of course, had in mind the example of Nazi Germany as the embodiment of a demonic national state.

He recognised that the ultimate concerns of humans are many and varied, and are not necessarily religious in nature. But he also warned that faith based on utopian or populist political ideals could become an idolatrous quasi-religion when directed at narrow concerns. The state in authoritarian ideologies is always a false idol that encourages and absorbs faith and presents a false object for worship; a utopian, nationalistic ideology and myth that harms rather than benefits humanity. Tillich applied this logic even to the Church, writing that ‘no church has the right to put itself in the place of the ultimate.’

Tillich was clear that God could not be a being in the Universe, else God could not have created the Universe. As we have mentioned, for Tillich, God was outside the Universe and beyond space and time, existence and essence. This broad and somewhat inchoate conception of God led other thinkers to accuse him of atheism, pantheism and even panentheism. But Tillich rejected all these labels. Instead, he continued to assert that we can speak of God only symbolically. Humans lack the knowledge and capacity to speak directly and literally about what God is. Instead, Tillich interested himself in the human relationship to the understanding of God as an object of ultimate concern. His perspective is always that of the finite human looking up toward the infinite. Religious symbols for Tillich are earthly finite things, but they point toward the infinite and the unreachable Universe beyond human understanding. They cannot define or describe God, but only point to Him, and thus to our most fundamental concerns.

Faith always includes doubt and an element of courage to sustain one’s faith in the face of such doubt. Tillich spoke of the social expressions of faith as a community of faith. But a community of faith (ie, shared ultimate concern) is always vulnerable to authoritarianism and must be ‘defended against authoritarian attacks’. By enforcing ‘spiritual conformity’, Church or scholarly authorities can turn faith into authoritarianism. The inclusion of doctrines of infallibility in the Church is an example of the kind of authoritarianism that Tillich resisted. For him, no one is infallible and all doctrines are subject to uncertainty and doubt.

To avoid the almost inevitable tendency toward institutional authoritarianism, Tillich writes that ‘creedal expressions’ of faith (ie, specific denominational beliefs, rituals and sacraments) must never be regarded as ultimate, but must always make room for criticism and doubt. Analogously, Tillich defined morality, not as a system of religion-inspired rules, but as the free expression by an individual of whom he or she is, as a person. He rejected rigid ‘moralism’ as coming from rules outside the individual. Instead, he conceived of morality as arising in each of us based on our feelings of love and justice for others in our world. Tillich believed that love infused with justice, not ideology, was the source of all morality and the unifying force to bridge the ontological separation that we experience as individual beings. He rejects the idea of a frozen concrete moral content: rules are merely a collection of current social wisdom about how to live and are not morality. Blind obedience to rules is mere submission to an authoritarian master. Morality comes from within.

Shock of the non-existence of a religious God strengthens knowledge of the power of your own being

When I think of my grandfather’s work, I always come back to the centrality of doubt to his thought. He concluded The Courage to Be (1952) with a much misunderstood final sentence perhaps inspired by his horrific experiences in the First World War:

The courage to be is rooted in the God who appears when God has disappeared in the anxiety of doubt.

When the God of theism has disappeared in the anxiety of doubt, what appears is the God above God or the power of one’s own being. I take this to mean that when you confront the shock of the non-existence of the religious or theistic conception of God, you become strengthened with the knowledge of the power of your own being, a power that is above and beyond theistic conceptions and is in fact the source of all of those religious conceptions. This interpretation has Tillich crossing the boundary of religious faith into the existentialist belief in his own personal courage and power as a being. And this, after all, is the purpose and conclusion of all philosophical thought that must always come back to the self, the human being trying to understand the Universe, but always returning to itself and its own subjective interests that ultimately create the only world we can live in, that of our own being.