Listen to this essay

20 minute listen

If you had to nominate the slowest, longest-living organisms on Earth, what would you picture? Among the vertebrates, some people might think of tortoises, whales or perhaps more obscure creatures like the Greenland shark, which can live for centuries. Others might imagine coral colonies, or perhaps an ancient tree: there are oaks in England that could be more than 1,000 years old, whereas in California, a few Bristlecone pines have been around for millennia, dating to around the formation of ancient Egypt.

But how about bacteria? Microbes, at the outset, may seem unsuitable candidates for the title of longest-living organism, since we’re so used to experiencing how they grow (and die) so quickly. If I wake up with a tickle in my throat, I get a feeling of dread because I know that, by the evening, I’m going to have a full-blown case of strep throat – the bacterial cells dividing like wildfire in my body. Some bacteria, like E coli, can double every 20 minutes. They can be killed off just as quickly, when faced with antibiotics or disinfectant.

However, E coli and other fast-replicating microbes don’t live in subsurface environments, where the conditions are ripe for a far more languid pace. In recent years, my fellow biologists and I have assembled evidence suggesting that the microbial world deep beneath the ground may be far slower than we think – perhaps remaining metabolically active for millions of years. I call these organisms aeonophiles – and by living as long as they do, they are rewriting the rules of biology itself. What are they doing down there? It turns out they might be waiting – waiting to return to the surface. But unlike cicadas or hibernating bears, these living things are holding on for events that might take centuries, millennia or even geological eras to arrive.

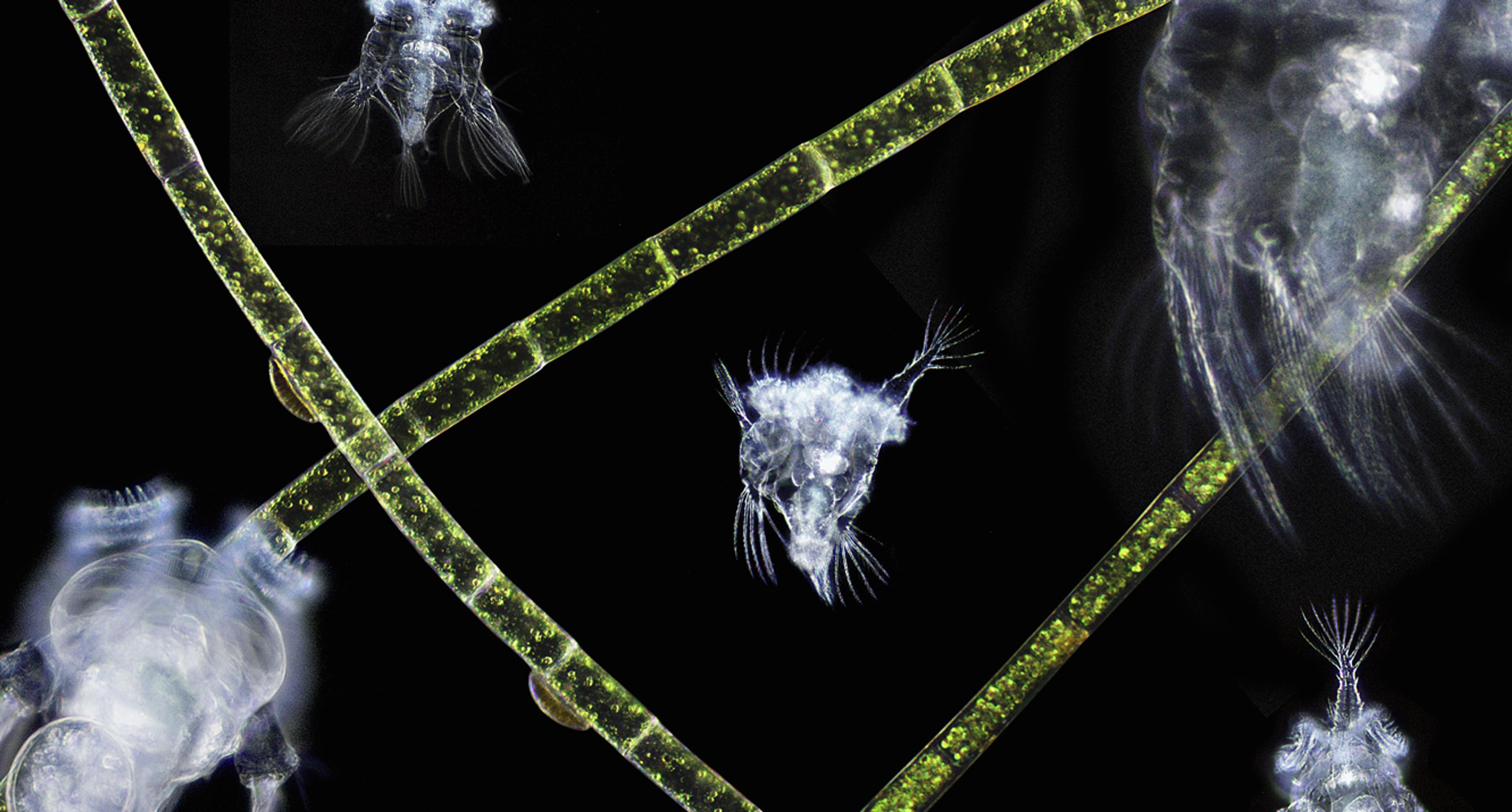

The steps that led to our discovery of this strange life can be traced back to advances in DNA technology in the 1980s. For the first time, biologists could sequence the DNA from microbes directly, in any environment, without first growing these microbes in a laboratory. In 1998, Philip Hugenholtz, Norman Pace and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley used this new technology to discover 12 deep branches on the tree of life in a Yellowstone National Park hot spring. The next year, Costantino Vetriani and Anna-Louise Reysenbach at Rutgers University in New Jersey and colleagues discovered even more new groups in deep-sea mud. None of these organisms had parallels in the known world of microbiology; they were entirely new to science. This new DNA-sequencing technology took off like wildfire, and scientists around the world, including myself as a young researcher, started discovering new types of life all over the place.

What we’ve discovered since has changed our conception of what life is like on Earth. Before these discoveries, it was unknown whether life can exist inside Earth’s crust. We now know that there is life under our feet, way under our feet. These subsurface-dwelling single-celled organisms are collectively called intraterrestrials, due to their parallels with the mystery and novelty of extraterrestrials. But, unlike space aliens, we know for certain that intraterrestrials exist.

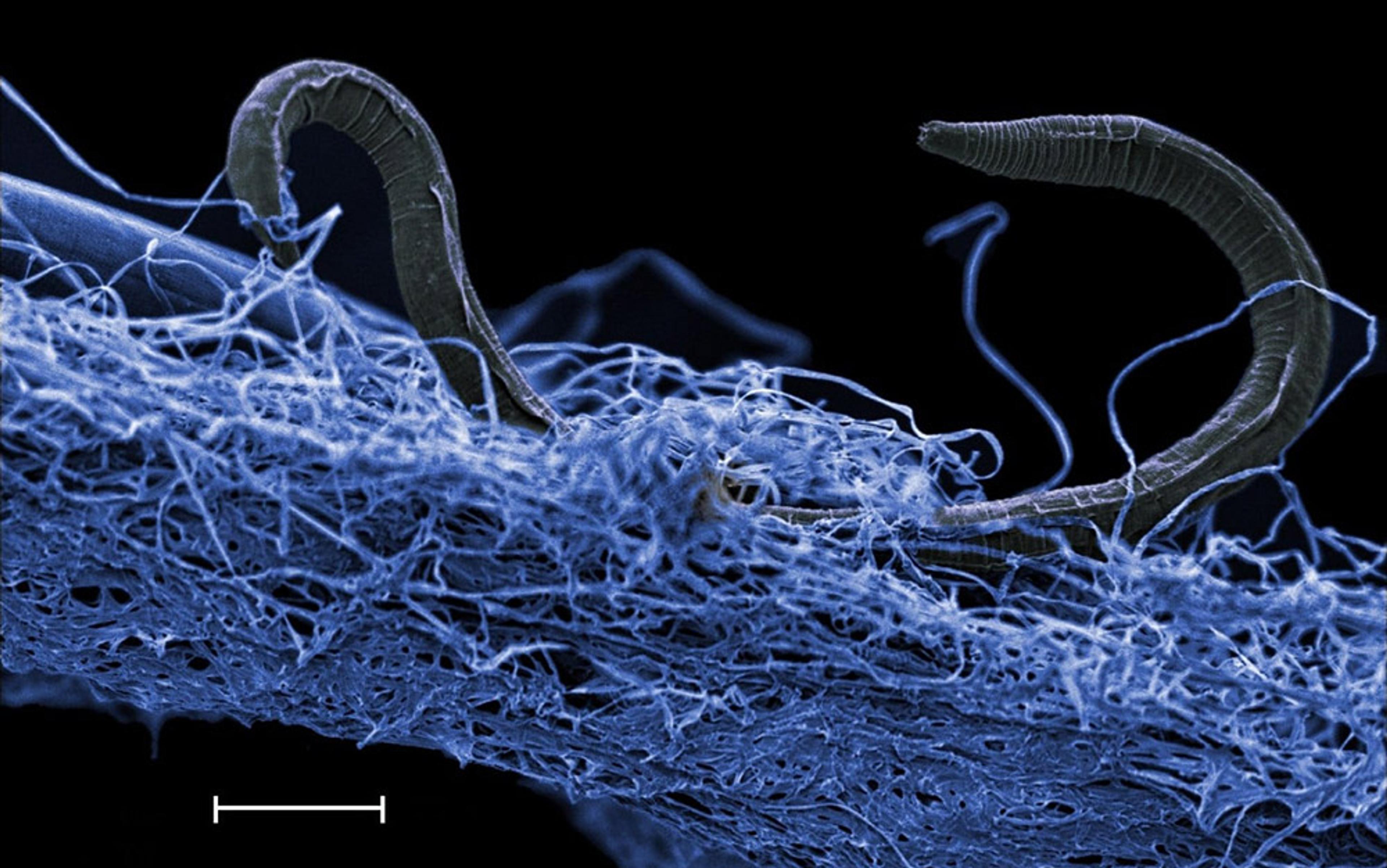

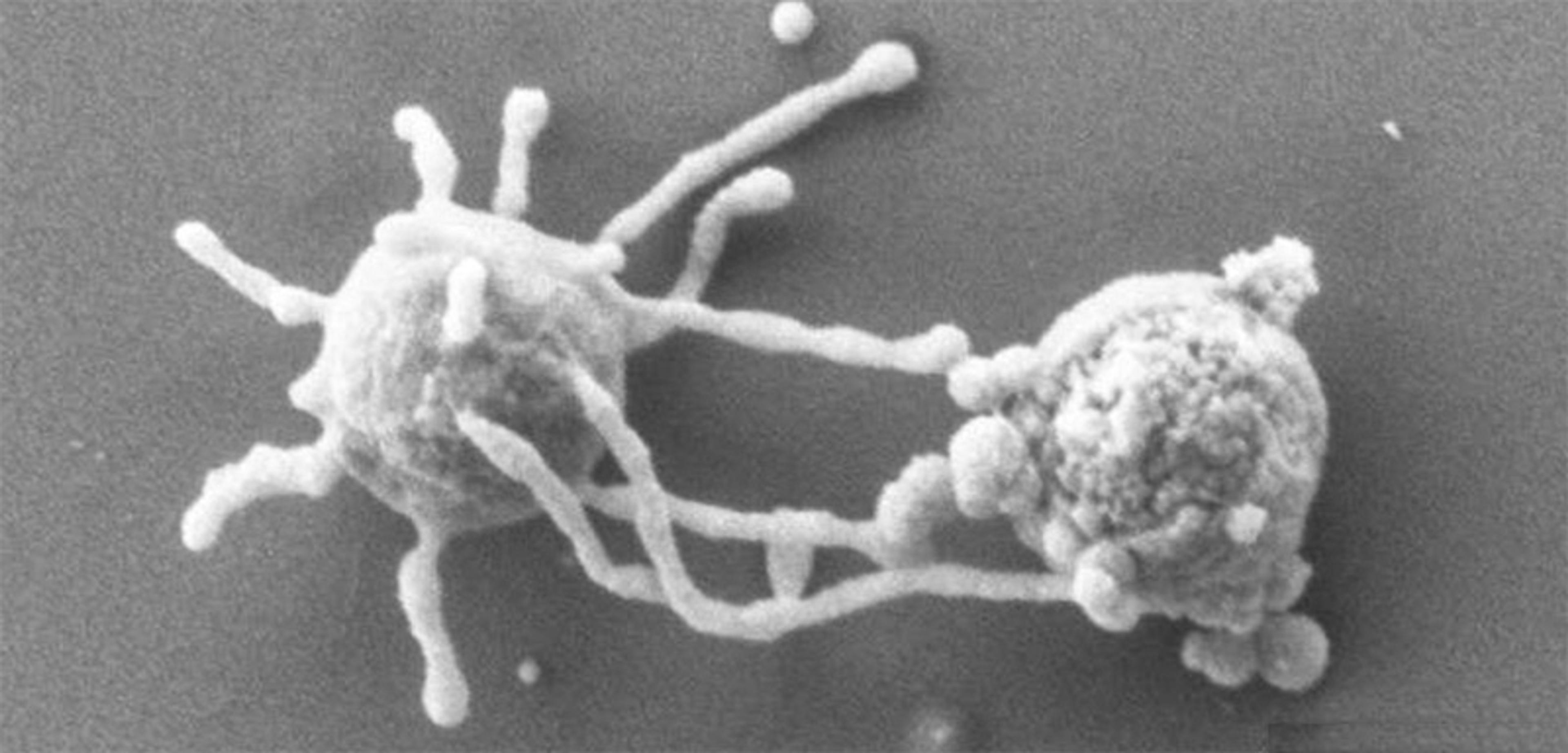

The author and research team drilling in Svalbard, northern Norway. Photo by Jon Leithe

Intraterrestrials comprise a vast still-mysterious ecosystem in Earth’s crust containing as many (or more) living microbial cells than are on Earth’s surface. We know this from scientists such as myself going out on scientific drilling ships that sample deep marine sediments or drilling deep into continental crust, laboriously counting the number of cells we find there, and extrapolating out to the rest of the world. The deepest we’ve found intraterrestrials thus far is about 5 km down. That’s deep enough for these intraterrestrials to never see the light of day, nor do they receive much food input from the surface world. Their world is mostly composed of tiny spaces between sediment grains or miniscule fractures in rocks. Rocks seem solid to us, but to very tiny life, rocks appear porous, with lots of places to live. From the few growing cultures that we have of these organisms, we know that many of them are tiny, and some have long appendages, such as the Asgard archaea and the Altiarchaeales, which may help them to hang on to their rock or sediment housing.

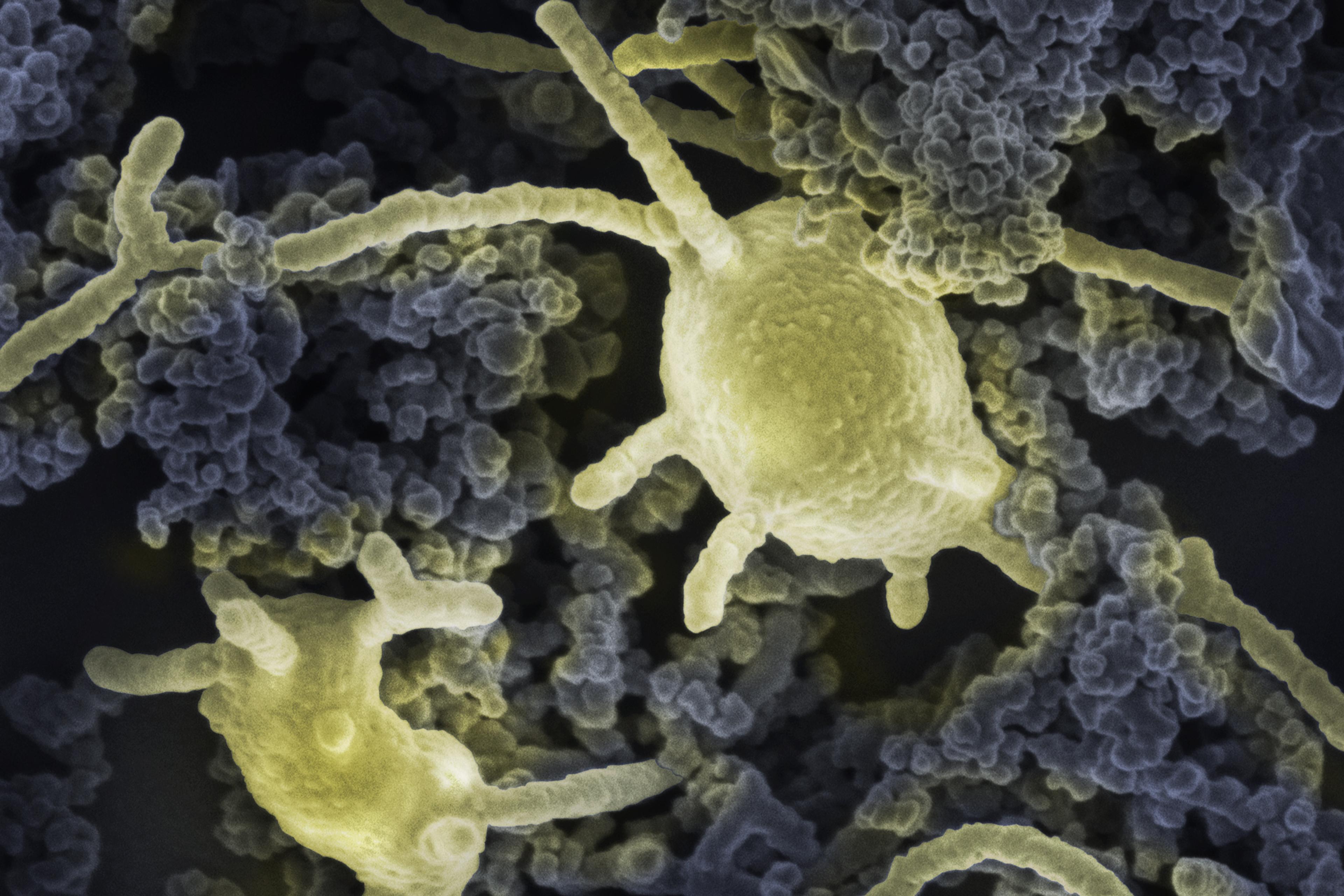

The intraterrestrial Lokiarchaeum ossiferum (‘skeleton-carrying’) is a member of the Asgard phylum, so named after Norse mythology because some of the first examples were found near the hydrothermal vent field Loki’s Castle in the Arctic Ocean. Its skeleton is probably a hallmark of Asgard archaea. Courtesy Rodrigues-Oliveira et al

Although deep geological sources of food and nutrition (often in the form of deep gases and hydrothermal fluids) can support life in some parts of the subsurface, thousands of years or longer might pass with little to no food inputs. This extreme scarcity has extraordinary implications for life. In much of this vast biosphere, there’s not enough energy to drive microbial cell division at anything like a normal rate. Before discovering these organisms, we had a narrower view of how much energy life requires and how long a single organism can stay alive.

But how long can a cell live like this? Theoretically, there’s no limit

The intraterrestrials are showing us that we were wrong; life can exist on orders of magnitude lower power and sustain their living cells for orders of magnitude more years than previously thought possible. This means that many of these living beings bump up against the energetic limits of life, and in the process seem to have cracked the code for near-immortality. These types of intraterrestrials have such extremely long lifespans that we need a new term to describe the type of extremophiles that they are. The word aeonophiles fits, since they like (-phile) long periods of time (aeon-). (If they could read, I’m sure they’d be die-hard subscribers to Aeon magazine too.)

Members of the Asgard archaea (left) were first collected from the Loki’s castle hydrothermal vent in the Arctic ocean in 2008. They include Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeia, Odinarchaeia and Heimdallarchaeia. Courtesy Wikipedia

Many of these aeonophile types of intraterrestrials survive on thousands of times lower power than the amount required to maintain a next-to-dead non-growing culture of normal bacteria. This means that even though the deep subseafloor is one of the largest ecosystems on Earth, hardly any of the microbes that live there are actually growing. They have 0.00001 per cent of the power that supports all other known types of cell growth on Earth, so even performing a single cell division is impossible.

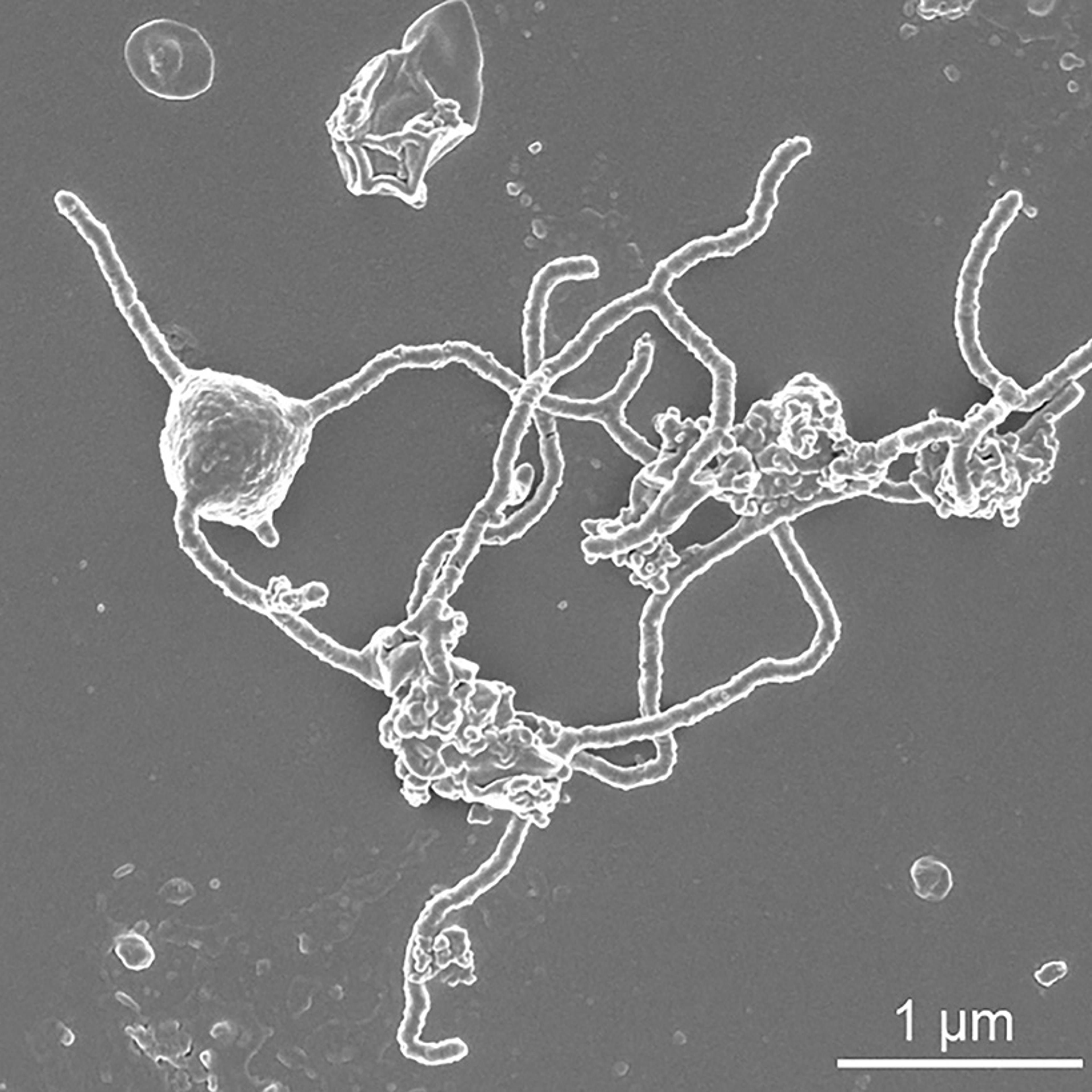

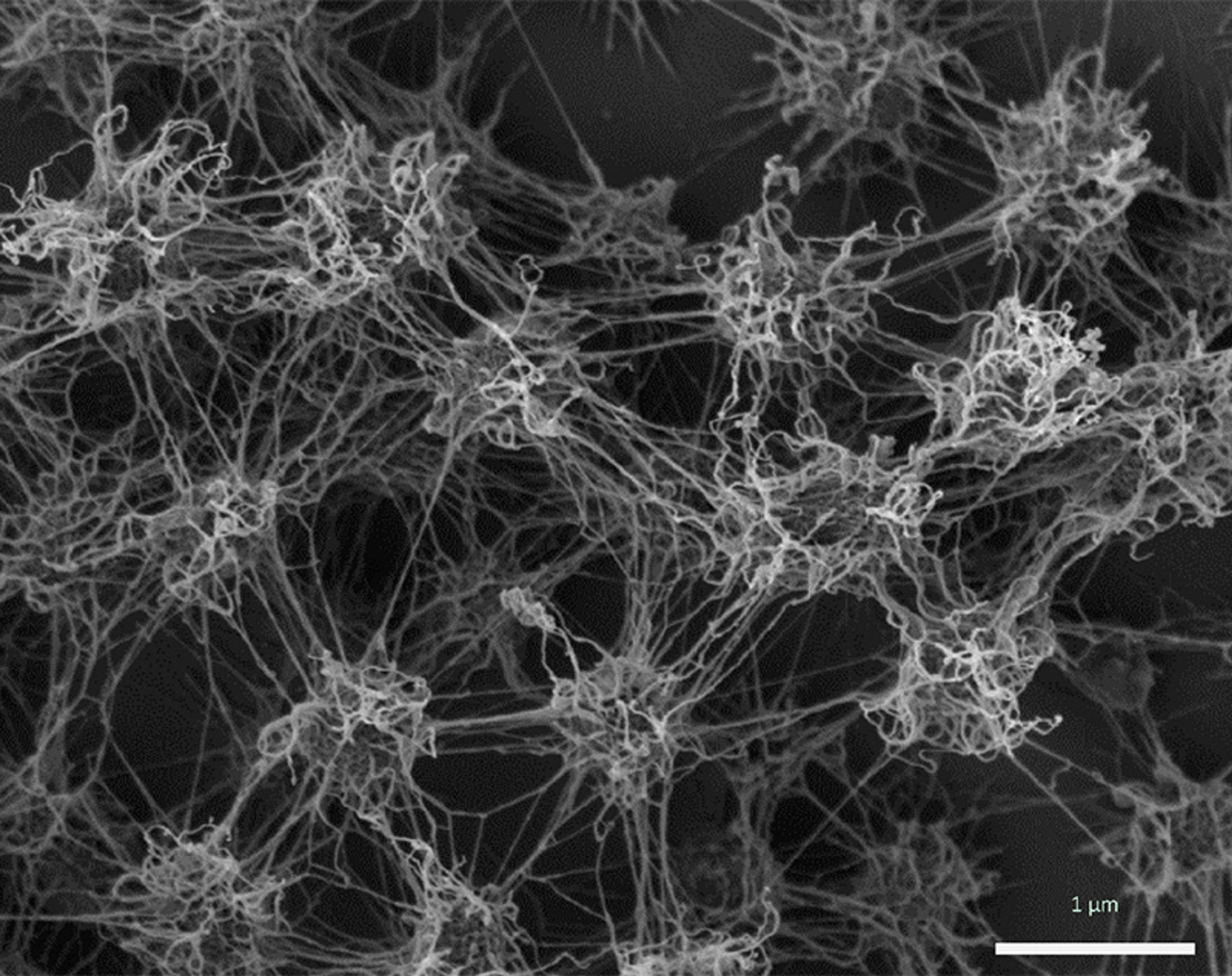

Candidatus Altiarchaeum hamiconexum cells within their biofilm. Cells appear fluffy due to their extracellular polymeric matrix and cell-surface appendages (‘hami’). Courtesy Probst and Moissl-Eichinger

Aeonophiles funnel all the meagre power that’s available to them into replacing broken body parts, not dividing into two new daughter cells. So, long-term metabolically active dormancy is the only option. But how long can a cell live like this? Theoretically, there’s no limit if it slowly replaces its broken bits over time. This brings up a real conundrum. On the one hand, if anything like immortality were common, then we would be surrounded by beings that were born sometime around the origin of life, which is not the case. But on the other hand, these aeonophiles seem like they could live forever.

Luckily, there’s a lot of temporal real estate between a 20-minute doubling time and immortality. What if the aeonophiles live for 500,000 years or a million years? The oldest sediments that have not yet metamorphosed into rock are about 100 million years old, so this is an upper limit on the age of an individual cell in marine sediments. Older rocks could have older cells, as long as the rock has not been buried to sterilising temperatures over the course of its journey around our tectonically active planet.

To us, they look like they’re doing nothing. As an analogy, over a geological timescale, the California coastline is a constantly churning mass of rocks, but on our human timescale, it is stable enough to build a house on, which can be passed on to our grandchildren. These houses must be sound enough to withstand the occasional earthquake, but they will not survive the reorientations of land as they are spun, submerged, and exhumed over the course of a few million years. To think like an aeonophile, we have to grapple with some incomprehensible timescales.

How did these organisms evolve to stop growing for thousands of years? To answer this, first we might consider what they would experience in their lifetimes. They wouldn’t be concerned about the length of a day. They’re buried so deep that they can’t detect the Sun anyway. They probably wouldn’t even notice the seasons. However, they might care about other, and longer, geological rhythms: the opening and closing of oceanic basins through plate tectonics, the formation and subsidence of new island chains, or new fluid flows brought on by slow cracks opening in Earth’s crust. The biology I was taught in school considered these events to be evolutionary drivers for a species, not an individual. For instance, Charles Darwin’s finches evolved new beak shapes because they had been isolated on an archipelago.

We know that animals adapt to the daily or yearly rhythms of their environment, but it seems ridiculous to argue that any creature could anticipate tectonic cycles. It may, however, be reasonable for the aeonophiles. An individual that lives for a million years might be evolutionarily predisposed to count on something as slow as island subsidence in the same way that we are evolutionarily predisposed to wait for the Sun to rise tomorrow. To fully understand aeonophiles, we may have to rethink what qualifies as an evolutionary cue.

You may also wonder: how does evolution work for an organism that seemingly never produces offspring? According to Darwin’s theory of natural selection, these cells must grow and make new progeny to evolve. But how? I don’t think Darwin had nongrowth in mind when he described survival of the fittest. The answer to the question at the beginning of this paragraph lies in the word ‘seemingly’. They’re not producing offspring in the places that we normally look for them, but there has to be a place or time when they do make progeny.

We need to jailbreak our brains from our implicit assumptions about lifespan

Luckily, we have a good model in short-term seasonal dormancy, which various surface organisms enter for months before emerging to reproduce. Here dormancy during winter has an evolutionary advantage: by avoiding harsh, cold conditions, dormant organisms get the chance to have larger populations than non-dormant organisms in the spring. This provides a head start, allowing them to pass along their dormancy genes to a larger population of progeny. Textbook Darwinian natural selection.

To imagine dormancy that lasts for thousands of years, we have to think of an event that aeonophiles could possibly be waiting for. If we encounter a dormant microbe in soil in winter, we can presume that it’s holding out for summer. What is the equivalent situation for a deeply buried marine sediment organism waiting for thousands to millions of years?

Before we answer that question, let’s first consider a thought experiment to jailbreak our brains from our implicit assumptions about lifespan. Imagine human lives lasted only 24 hours. You’d be born at midnight, rebel against your parents at breakfast, settle down and have babies just before lunch, and pick up fishing as a retirement hobby around dinnertime. By midnight, your loved ones, who themselves were born only a few hours ago, would huddle close and hold your hand as you’d pass away peacefully at the ripe old age of a day. If everyone did that, hundreds of human generations would come and go within a single winter. Throughout that time span, which would represent a significant chunk of human history, the deciduous trees would remain brown and lifeless. The permanent deadness of trees would be taken as an undisputed fact, and scientists like me would probably apply for grants to understand whether or not trees are alive, given that they don’t seem to grow or make progeny. Of course, if you stretched back far enough, humans would have been present for the fall or even summer, but that might have been so many generations back that a stable form of writing had yet to be invented. We 100-year-lifespan humans know that trees are just waiting to take advantage of the summer sun. But the day-lifespan humans would be stumped.

When we think about life in the subsurface, are we like day-lifespan humans contemplating a tree? Are long-lived aeonophiles waiting for wake-up cues we don’t recognise because our lives are too short to see them? What is even the point of living for hundreds of thousands of years anyway? There must be some reason these aeonophiles stick around so long.

Seasonal cycles are way too fast. The only things slow enough are geological processes. For instance, island subsidence, floods or droughts often occur on 100- to 1,000-year cycles. Submarine landslides, earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions might shift materials around on even longer timescales, exposing aeonophiles to new food sources that coax them out of dormancy after hundreds of thousands of years. It seems odd to say that a microbe is adapted to wait for something as infrequent as a volcanic eruption, but you can rely on them to happen, as long as you’ve got time to wait.

The author taking samples from a gassy deep subsurface spring. Photo by Jacopo Pasotti

If we really let our imagination run wild, individual microbes might be adapted to events with even longer periods, like interglacial cycles, which shift every 30,000 years or so. Or the slow movement of tectonic plates. As a new seafloor pops up in midocean ridges, the existing seafloor is constantly pushed from the middle of the ocean, until it eventually jams into a continent in the slowest-motion train wreck ever.

Some marine sediments – and the aeonophiles that live in them – will get dragged down on the subducting plate and destroyed. Even for extremophiles, the mantle is an evolutionary dead end. However, some seafloor sediments survive these collisions – rather than subducting, they are scraped off and shoved onto a continental plate. Could all this piling up, faulting and burbling up to the surface be what the aeonophiles are waiting for? Is this an aeonophiles’ version of summer?

Living on human timescales, it’s hard to say for certain. However, we do know that the aeonophiles are showing us that some Earthlings can live for many thousands of years or longer. In my opinion, these are fundamental discoveries about the nature of life on Earth. In fact, I believe that the discovery of ultra-long-lived creatures is up there with the discovery of hyperthermophiles, microbes that thrive at temperatures above the boiling point of water. When hyperthermophiles were discovered in the 1960s, it blew open our understanding of where life might exist in the Universe. I foresee a similar seismic shift from the discovery of aeonophiles.

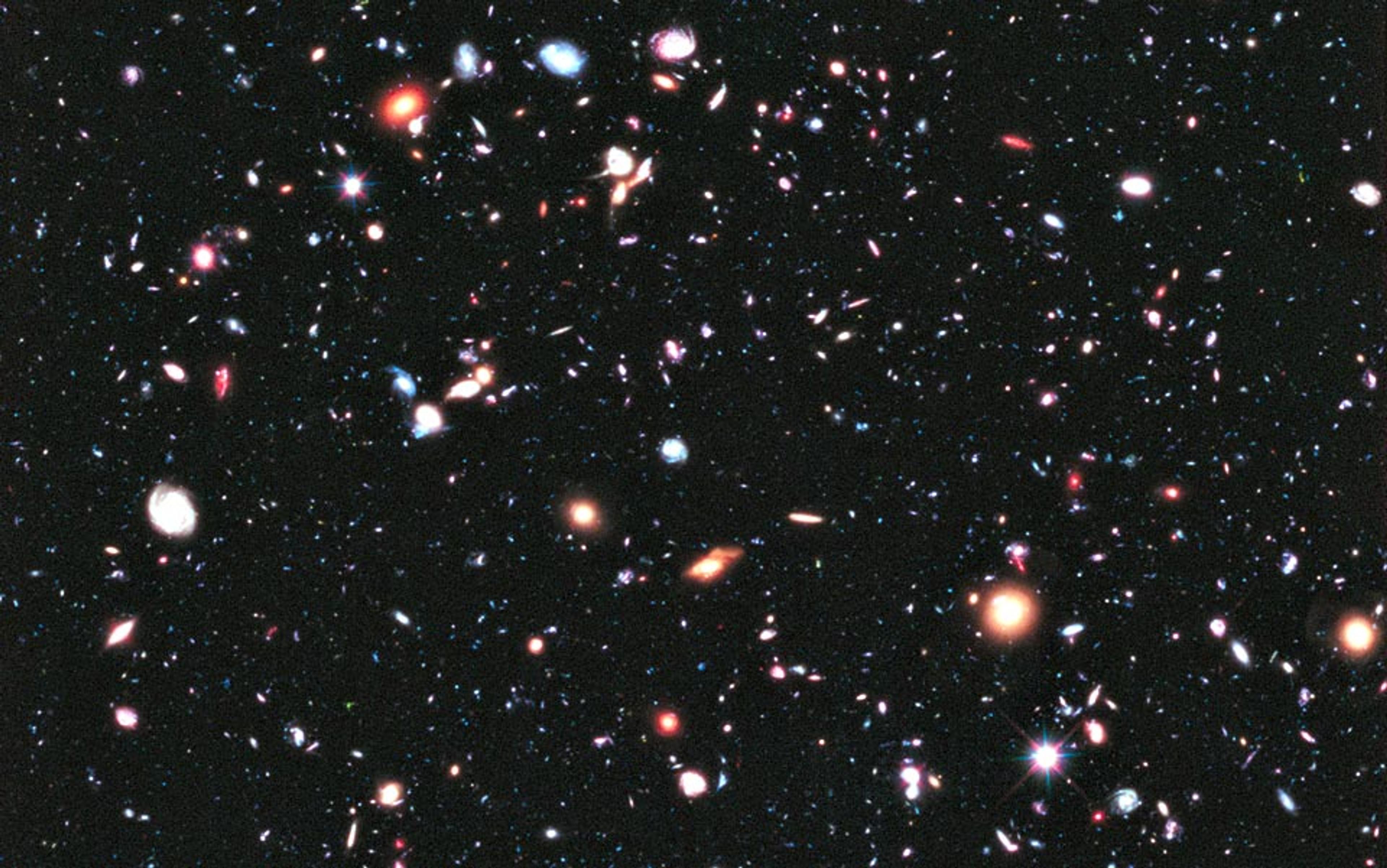

The existence of such organisms greatly expands the window of time during which we can look for biomarkers in the cosmos. In fact, they raise the troubling possibility that, if life on other planets is extremely slow, it might also be nearly impossible to detect. As we examine other planetary bodies, we look for changes that might signify that something is alive and doing work on that planet. But if that life is extremely slow, we may not realise we’re looking at it because it doesn’t change much while we’re observing it. It is not impossible that beneath the surface of Mars or Europa, things are alive and functioning much more slowly than the life that we’re used to.

By living as slow as they do, aeonophiles prompt us to consider how we define life and non-life. How can we scientifically distinguish between the two? For answers, I believe we need to think of life, in its most basic function, as an energetic phenomenon. And to do that, it’s necessary to look at it through the lens of thermodynamics.

In their book Into the Cool (2005), the scientist Eric Schneider and the writer Dorion Sagan suggest that life and non-life exist in a continuous line. At one end of the spectrum are non-living systems at energetic equilibrium; and at the other end are living systems continuously creating further energetic potential to make sure they stay well out of equilibrium. So, one way to define life would be that it is good at creating energetic opportunities to push things far out of equilibrium.

If we’re talking about energy, we have to talk about the second law of thermodynamics, which is driving it all. The law says that, in a closed system, entropy – roughly the number of ways a system can be arranged – tends to increase overall. As entropy rises, less of a system’s energy can be used to do work. We’ve long known that life is good at producing entropy; just look at the heat radiating from our bodies and even whole cities. Non-life can produce entropy too, though, so how does this help us tell the difference?

Aeonophiles show us that life has more creative ways of producing entropy than we thought possible

According to non-equilibrium thermodynamics, it is life’s propensity for continually pushing systems back out of equilibrium that sets it apart from non-life. Once things are well out of equilibrium, entropy can be produced in the race to regain equilibrium. Crucially, life seems to be better than non-life at creating new systems in which entropy can be produced. An eddy in a stream is not alive, but for a short amount of time, the water molecules become a whirlpool to maximise entropy production through energy dissipation from the system. Life does this too, but it’s more sophisticated and effective in its approach. Non-life makes whirlpools, but life dams the river to go whitewater rafting on those whirlpools. Non-living asphalt heats up when sunlight hits it, creating a bit of entropy, but a rainforest places leaves at different levels capturing every last photon of light and turning it into biomass that will support an entire ecosystem of animals and fungi that produce more entropy per ray of light than asphalt ever could.

What the aeonophiles do for us is to show us that life has more creative ways of producing entropy than we previously thought possible. If the point of life is to create more entropy by spreading out its production over increasingly large scales of space and time, then this task seems tailor-made for aeonophiles. Simply by living for aeons, they may stretch out entropy production for longer timescales, maximising its final tally for the second law. Finding such an outlandish new way to create opportunities for entropy production supports the idea that this opportunity for entropy creation is, itself, the why of life. In short, life happens because the second law of thermodynamics demands it. And the aeonophiles, by their very long-lived existence, drive that point home for us.

Even though they may seem extraordinary to us, individuals that live for thousands of years or longer may be ordinary on Earth. In addition to showing us that life is far more diverse than we thought, and can use energy and time in ways we would never have dreamed up on our own, aeonophiles might be key to understanding why life exists. They’re showing us new ways for life to conduct its delicate dance with energy and entropy. As we continue to learn more about these strange intraterrestrials, and the aeonophiles among them, I believe we will continue smashing our preconceived notions of how life itself is supposed to work, one barely breathing cell at a time.