Listen to this essay

20 minute listen

In 1705, the Anglo-Dutch physician and philosopher Bernard Mandeville anonymously published a poem called The Grumbling Hive: Or, Knaves Turned Honest. He described a vast community of bees – a transparent metaphor for contemporary Britain – and the mechanisms of its wealth. In the hive, each bee works for its own personal gain, every profession has its cheat, and everyone exploits the passions of others. But the welfare of the community is not endangered:

Thus every part was full of vice,

Yet the whole mass a paradise; …

The worst of all the multitude

Did something for the common good.

Even more scandalously, when the insects did implement moral reform and forced themselves to live according to honesty and virtue, the community fell into a downward spiral.

The British Bee Hive (1867) by George Cruikshank. Courtesy the British Museum

In 1714, and in an enlarged edition in 1723, Mandeville published the prose volume that made him infamous: The Fable of the Bees: Or, Private Vices, Public Benefits. The original poem was reprinted with a series of commentary essays in which Mandeville expanded upon his provocative arguments that human beings are self-interested, governed by their passions rather than their reason, and he offered an explanation of the origin of morality based solely on human sensitivity to praise and fear of shame through a rhapsody of social vignettes. Mandeville confronted his contemporaries with the disturbing fact that passions and habits commonly denounced as vices actually generate the welfare of a society.

The idea that self-interested individuals, driven by their own desires, act independently to realise goods and institutions made The Fable of the Bees one of the chief literary sources of the laissez-faire doctrine. It is central to the economic concept of the market. In 1966, the free-market evangelist Friedrich von Hayek offered an enthusiastic reading of Mandeville that anointed the poet as an early theorist of the harmony of interests in a free market economy, a scheme that Hayek claimed was later expanded on by Adam Smith, reworking Mandeville’s paradox of ‘private vices, public benefits’ into the profoundly influential metaphor of the invisible hand. Today, Mandeville is standardly thought of as an economic thinker.

There is no question that Mandeville ‘discovered’ the division of labour, defended luxurious consumption and, most important of all for economic historians, expressed the view that the pursuit of individual self-interest can be beneficial to society. But the dominance of economic readings of Mandeville has overshadowed the breadth of his interests and writings, the project behind them, and in general his stature as an accomplished philosopher whose influence on the Scottish and European Enlightenment remains to be reconstructed in depth.

Mandeville never made economic issues the focus of his analysis, and his arguments concerning trade, luxury and wealth form only one part of a broader examination: his psychological analysis of self-love and of the social effects of the hidden workings of pride and shame.

Mandeville thought of himself as a reader of disguised human motives, an anatomist of human nature, ready to show people what they are, rather than what they should be. He would accomplish this by keenly analysing human behaviours and institutions in terms of their motivating passions. From thoughtful observation and personal experience of these passions, he attempted to draw general principles about human nature, principles that would stand in analogy to the laws that govern the natural world. For these very reasons, David Hume listed him as one of those who had begun to place that ‘science of man’ on firm ground, along with John Locke, Lord Shaftesbury, Joseph Butler and Francis Hutcheson.

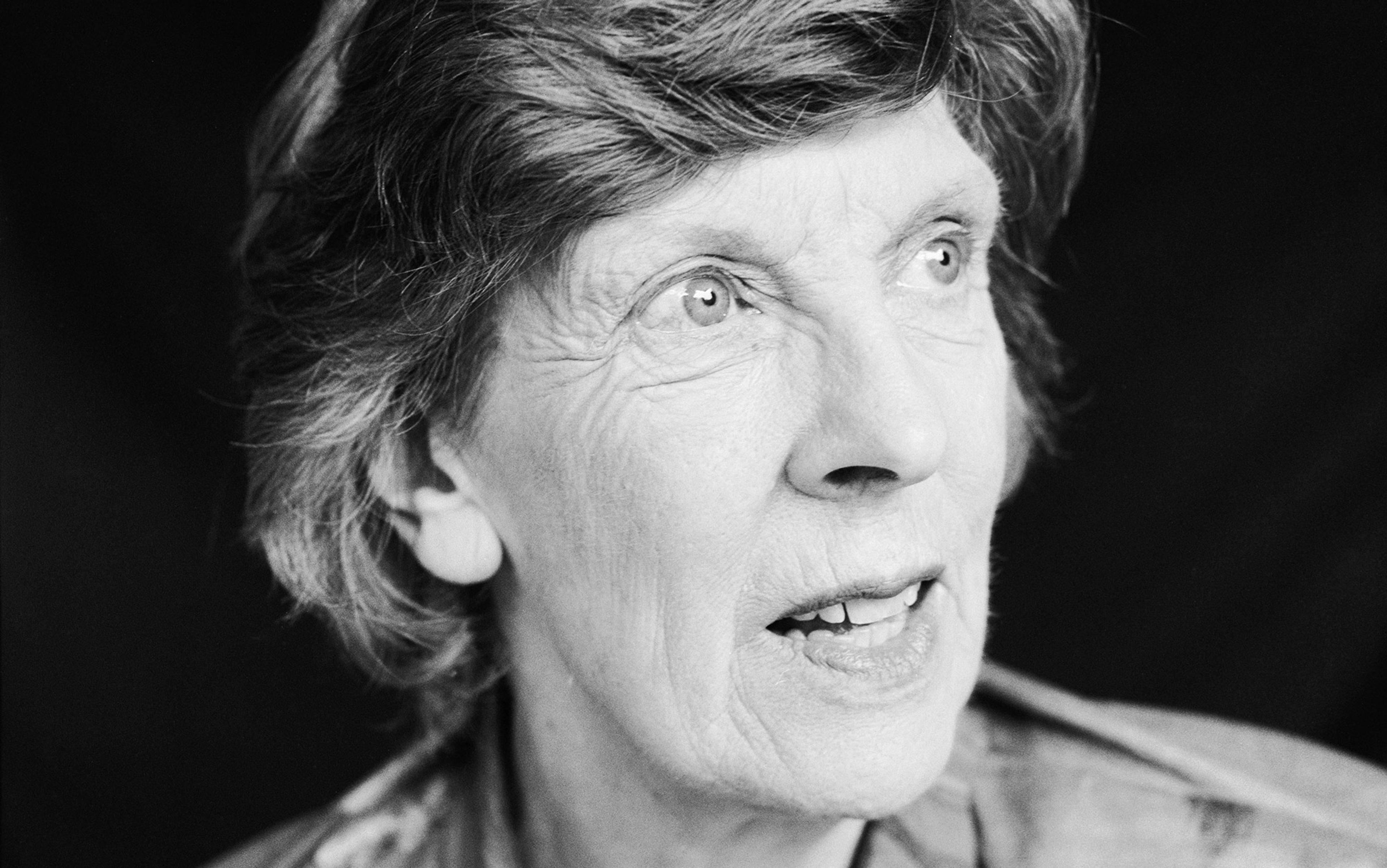

Unknown man, formerly known as Sir James Thornhill but now thought to be a portrait of Bernard Mandeville. Courtesy the National Portrait Gallery, London

Mandeville was well prepared for this task. Born in Rotterdam in 1670, he later graduated in medicine and philosophy from the University of Leiden, and trained as a medical physician, before settling in London. There he practised as a specialist in hypochondria and nervous disorders, meeting his patients for long sessions of therapeutic dialogues in his private quarters (not dissimilar to the later practice of psychoanalysis, in fact). This experience produced his Treatise of the Hypochondriac and Hysteric Passions (1711, 1730).

In Mandeville’s view, human beings are driven by their self-regarding passions. We are always feeding them, even when they act contrary to self-interest – we feed them to the point of deceiving ourselves about our own motivations. Among the passions, the predominant force is pride:

that natural faculty by which every mortal that has any understanding over-values, and imagines better things of himself than any impartial judge, thoroughly acquainted with all his qualities and circumstances, could allow him. We are possessed of no other quality so beneficial to society, and so necessary to render it wealthy and flourishing …

Pride, like other self-centered passions, is necessary for the flourishing of society, and Mandeville identifies in the self-regarding nature of human individuals the original, natural disposition to sociability. The very human capability to socialise is grounded in the operations of pride and the fear of shame, which together Mandeville calls the passion of ‘self-liking’. These are the sentiments in which we overvalue ourselves, and which constantly rely on other people to be confirmed, reassured and gratified. Our pride requires the company of others; our pride creates the need to socialise, to form society.

The history of sociability is a continuous process of modifying codes and expressions of deference

For Mandeville, sociability is the result of an evolutionary process. He characterised it as the outcome of a gradual, spontaneous progression, achieved not by the defeat of self-regarding passions but by their domestication into forms compatible with social cohesion and civic growth. Along with a high opinion of themselves, individuals have a profound desire for others to share in that opinion. But human pride is always accompanied by the secret apprehension that the value we place on ourselves is not entirely justified. The natural symptoms of the high self-esteem that human beings display and experience in their fellows are mutually offending, to the point of prompting individuals to conceal the enormity of their self-regard. We learn to take pride in hiding our pride.

The different forms of reciprocal adulation therefore have as their motivating force the constant need of human nature to experience and express self-liking. And this holds throughout the history of civilisation. The history of sociability is a continuous process of modifying codes and expressions of deference. It is ‘no more’, he writes, ‘than the various methods of making ourselves acceptable to others, with as little prejudice to ourselves as is possible …’

Since the desire for praise is a universal property of human nature – central to Mandeville’s philosophical anthropology – a theory of sociability requires a sociohistorical account in order to show how self-regard assumes different shapes in different historical contexts. The acts and words that are publicly praised or blamed in one age differ from another; codes of honour and shame almost always vary between cultures. Mandeville’s focus on the manners and habits of his contemporaries is thus a fundamental feature of his philosophical anthropology.

In early 18th-century Britain, the language of manners and its key term ‘politeness’ had become a crucial model for honourable behaviour, and a new way to formulate the ideal of respectability. By tracing the history of contemporary male and female codes of honourable behaviour from the perspective of his theory of passion, Mandeville denounces the moral hypocrisy of the overly confident and fashionably well-bred, who deluded themselves into believing that their good manners are equivalent to virtuous conduct. He shows that the rituals of politeness and honour are an exemplary expression of a spontaneous and artificial order resulting from a natural disposition of the human passions and the perennial need to be liked. The great and the good were no better than the bees; the only difference was that they happened to wear periwigs and fontanges.

In Mandeville’s first prose works, he assumed a female persona, and in all his writings he maintained a keen interest in the life of women and the ‘double standard’ applied to them in education, social status and the satisfaction of sexual desire. In The Virgin Unmasked: Or, Female Dialogues Betwixt an Elderly Maiden Lady and Her Niece (1709), an experienced woman warns her niece about how men seduce and enslave women, in stark contrast to the rose-tinted image of love found in popular tales of romance. They discuss gender education in a male-dominated world, where women are subjected to their fathers’ and husbands’ control. This oppression not only undermines women’s character but also condemns them to a diminished social role, which further exposes them to men’s manipulations by making them vulnerable to nefarious tricks and traps.

Mandeville’s ‘science of man’ took seriously the position of women in a deeply misogynistic society. He continued his examination of gender in a series of essays in the periodical The Female Tatler, published a year later. Two sister journalists vindicate women’s right to a social and cultural role: men have excluded women from education and from writing history, from reading and of being read in books, thus maintaining male domination by handing down a culture in which women’s fate is submission, their most precious quality is meekness, and their public reputation for virtue is based solely on chastity.

In 1711, the periodical The Spectator bluntly summarised this double standard of male and female honour:

The great point of honour in men is courage, and in women chastity. If a man loses his honour in one rencounter, it is not impossible for him to regain it in another; a slip in a woman’s honour is irrecoverable.

Chastity, then, is essentially synonymous with passivity, with avoiding dishonour; the opposite of the activity that constituted male honour. Female virtue is not only determined exclusively by the relationship with the opposite sex, but is presented as essential to female nature. While men had the opportunity to act courageously and regain their tarnished honour, women had to be chaste – or not. Once lost, their honour cannot be recovered.

The duel is a paradigmatic expression of the function of pride and shame in the development of sociability

The first decades of the 18th century, during which Mandeville wrote and published his major works, were the golden age for duelling in Britain. Challenging someone to a duel and behaving politely to an individual before attempting to kill him was a custom of enormous social significance. Due to its paradoxical conceptual framework – where courage and warlike virtues are associated with the ruling classes, and those latter with noble birth and moral sensibility – participating in this highly ritualised form of attempted homicide-suicide was considered the best way to acquire a reputation of respectability and even virtue. The willingness to duel remained an eccentric but fundamental feature of gentlemanliness. However, duels were forbidden by almost all European legislations and condemned as a mortal sin – it was seen as a preposterous waste of noble or gentlemanly blood.

Mandeville intervened in the debate on duelling in almost all his writings. With the provocative attitude characteristic of his style, he used traditional arguments from courtesy literature to advance a defence of duelling as a useful deterrent for those who might break social norms. But Mandeville also makes the duel a paradigmatic expression of the function of pride and shame in the development of sociability. Duelling, which testifies to the prevalence of the fear of shame over the fear of death, represents for Mandeville the most extreme expression of a fundamental feature of human nature, one that stands at the very roots of sociability: the tendency to strive for social recognition, acting in accordance with an idealised self-image to satisfy the desire for pride and the fear of shame, absorbed in a practice of self- (and mutual) deception. ‘The same passion that makes the well-bred man, and prudent officer, value and secretly admire themselves for the honour and fidelity they display,’ he writes, ‘may make the rake and scoundrel brag of their vices and boast of their impudence.’

In the second part of the Fable of the Bees, Mandeville further anatomises human nature through a cutting analysis of the ‘polite gentleman’. The decisive test is to examine this gentleman’s attitude when faced with the challenge to a duel. It cannot be denied that duelling is a mortal sin for the gentleman, but shirking it is out of the question:

Entirely to quit the world, and at once to renounce the conversation of all persons that are valuable in it, is a terrible thing to resolve upon. Would you become a town and table-talk? Could you submit to be the jest and scorn of public-houses, stage-coaches, and market-places? Is not this the certain fate of a man, who should refuse to fight, or bear an affront without resentment?

Duellists may deceive themselves with the rhetoric of honour, but they are in fact motivated exclusively by pride and shame. The inner conflict faced by a man challenged to a duel is not about his supposed ‘sense of honour’ or his religious principles, but about the two basic passions that rule human nature: self-love (the instinct of self-preservation) and self-liking (the love of praise, the fear of shame). In Mandeville’s final diagnosis: ‘Vanity, shame, and … constitution, make up very often the courage of men and virtue of women.’

Even if the good and evil of honour and dishonour are illusory, shame is very real, with its own psychological and physiological symptoms. Mandeville described them in detail: ‘though shame is a real passion, the evil to be feared from it is altogether imaginary, and has no existence but in our own reflection on the opinion of others.’ He sees the taming of the natural impulses of lust through the education of shame as a paradigmatic example of how passions in society are restrained and modified. In Mandeville’s time, human beings were so successfully trained to feel shame that the distinction between lustful men and chaste women appeared to be an entirely natural difference rather than a socially determined one.

Women’s love for their children can be overwhelmed by a more powerful type of self-love: the fear of shame

Women, for Mandeville, are not naturally ashamed of their sexuality, but they are educated to feel shame. By simply observing the behaviour of modestly educated adult women, girls will learn to be careful about covering themselves in front of boys, and at a very young age they will be ashamed to show their legs, without even knowing the reasons why such an act is blameable. Educating the young for life in society means stimulating their pride – that is, increasing their fear of shame in relation to behaviour, words or attitudes that are considered blameworthy for their sex. In this pedagogy of shame, women are trained to be modest, men to be brave. Chastity and courage are both ‘artificial’ passions, the outcome of evolution, conventions and education.

While moral instruction trains all members of polite society to repress their sexual impulses, women are forced to exercise greater self-control than men. For Mandeville, simply because the male sexual appetite is considered to be more violent and uncontrollable, there is less expectation that men follow the norms of modesty. They can take greater liberties, while women have to carry a heavier social burden. This double standard allows men to pursue sexual gratification without much fear of public disapproval, but women are left to defend their reputation of chastity against social censure: ‘it is the interest of the society to preserve decency and politeness; that women should linger, waste, and die, rather than relieve themselves in an unlawful manner’.

In The Fable of the Bees, Mandeville uses a scene from everyday life to illustrate the social effects of double standards, explaining from a woman’s point of view the dynamics that lead to infanticide. While people from good families have the possibility to ‘sin’ unnoticed, servants and poor women rarely have the chance to conceal a ‘big belly’. A girl of good birth who is left penniless and forced to work as a maid can preserve her chastity for years, yet still encounter an unhappy moment when she surrenders her honour to a deceiver with power over her, who then neglects her. Mandeville observes that women like this are so overwhelmed by the social insistence on female chastity and the fear of public shame that they are likely to risk abortion and infanticide. The more intensely she fears shame, the more cruel her intentions will be, either towards herself or towards her unborn child. In such situations, women’s natural love for their children can be overwhelmed by a more powerful, socially inculcated type of self-love: the fear of shame. For Mandeville, contrary evidence that chastity is an artificial virtue peculiar to civilised society can be found in the fact that ordinary prostitutes rarely kill their children. This is not because they are less cruel or more virtuous, but because they have lost their modesty to a greater extent, meaning the fear of shame has little effect on them.

Infanticide is to artificial chastity as the duel is to artificial courage: a bloody tribute to the cult of the self on which modern honour is grounded. In Mandeville’s naturalistic account of sociability, the ‘virtues’ of chastity and courage are accounted for as the spontaneous social effects of pride and fear of shame, resulting from that key disposition that makes men fit for society: self-regard. Polite modern manners are but the latest stage in the history of pride: ‘the invention of honour … was an improvement in the art of flattery, by which the excellency of our species is raised to such a height, that it becomes the object of our own adoration, and man is taught in good earnest to worship himself.’

For Mandeville, morals and manners evolved over time, without any planning or design, from the dynamics of pride and shame and from the need to mask our natural, inescapable self-centredness. Civil society is the product of a gradual process and it is determined by man’s continuous efforts to satisfy a multiplicity of needs – the most prominent of which is what we call today ‘desire for recognition’. In this sense, the mechanisms by which self-gratifying motives produce socially advantageous outcomes – by which private vices are channelled into public benefits – are far from being attributable simply to the spontaneous order of the market. Before being ‘utility-maximisers’, human beings are primarily ‘esteem-seekers’, and their self-interest is always intertwined with the bottomless desire for recognition from others. Mandeville’s anatomy of human nature remains true today.