Listen to this essay

33 minute listen

Over the past century, historians of the United States have made increasing efforts to challenge the predominant 19th-century view that slavery in the US South was somewhat a benevolent institution. The old, idealised and paternalistic understanding of the history of slavery featured prominently in novels and motion pictures like Gone with the Wind (1939). Ulrich Bonnell Phillips, in his 1918 survey of American slavery, and other influential historians promoted this distortion too, claiming that slave owners in the US South treated their enslaved property with kindness, by providing them decent rations of food and good clothing, while encouraging the formation of stable family ties, education and Christianity.

In the years between the First World War and the Second World War, the historians W E B Du Bois and Carter G Woodson challenged this misrepresentation, stressing the profits made by US slave traders and owners, and underscoring the cruelty of bondage in the US. Later, the historians Frederic Bancroft and Kenneth M Stampp followed suit, noting the ubiquity of family separation and sexual violence, and the near-impossibility of emancipation. The misleading view of slavery as a benign institution didn’t survive the post-Second World War period, which brought racism into new disrepute. However, into the 1960s and beyond, some scholars continued to see slavery in Latin America, especially in Brazil, as less significant and milder than in the US. There were different reasons for this view, some deriving from the fact that the US was a Protestant country in a mostly Catholic hemisphere. Catholicism predominated in French, Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the Americas, and the strong influence of the Catholic Church on Iberian legal codes and custom influenced the practice of slavery. In the French and Spanish colonies in the Americas, as well as in Brazil, the doctrines of Catholicism gave enslaved people some rights, including the right to marry and the ability to buy their freedom.

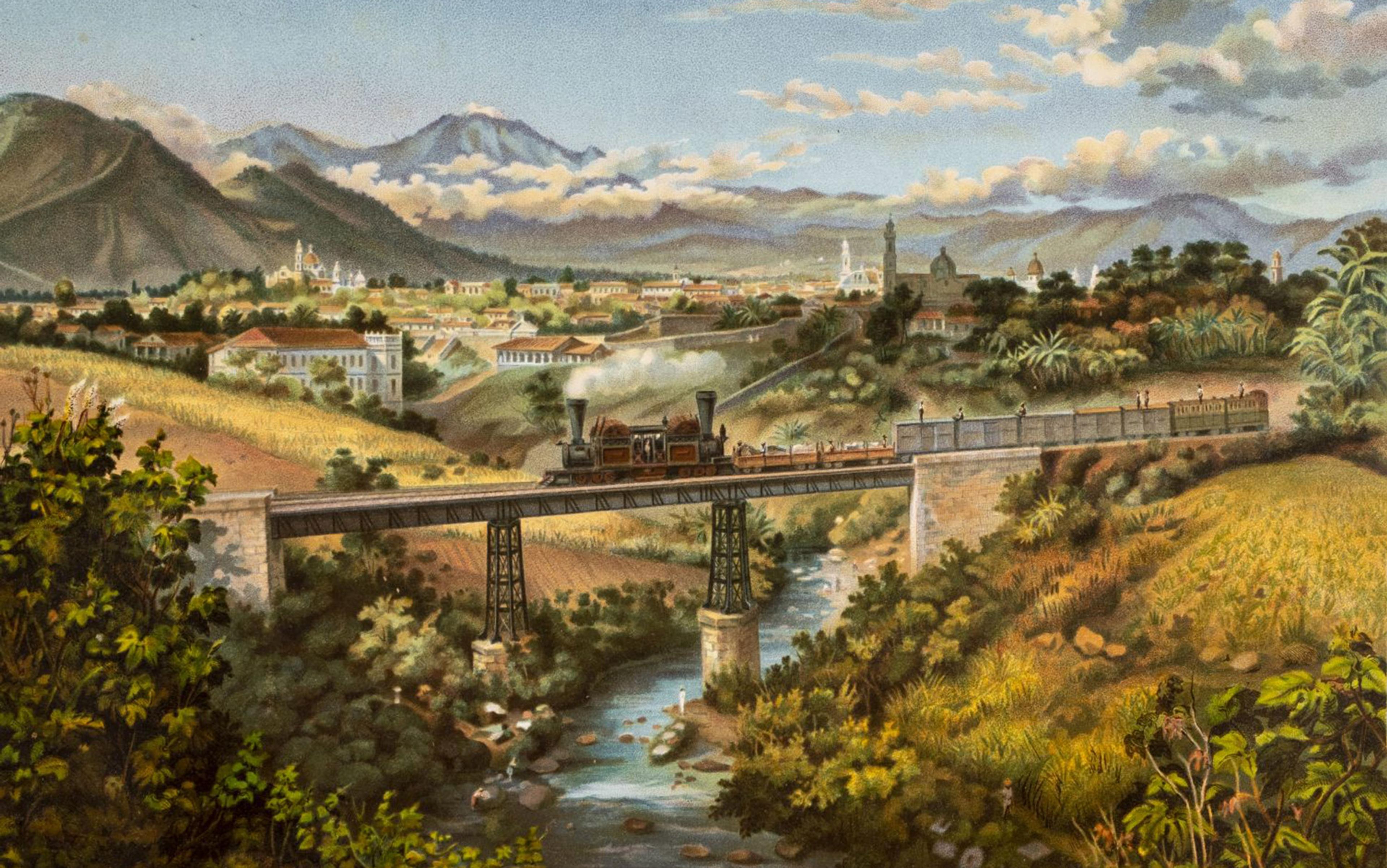

Enslaved people harvesting coffee, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (c1882). Courtesy Instituto Moreira Salles

Postwar US scholars who saw Latin American slavery as less severe than the US version drew heavily on the earlier work of the Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre and the US historian Frank Tannenbaum. Freyre’s book The Masters and the Slaves, originally published in 1933, was translated into English in 1946. Freyre went as far as to suggest an image of Brazil as a country virtually without racism, in contrast with the US. Over the past 50 years, however, historians like Florestan Fernandes and Abdias Nascimento have dismantled this 20th-century liberal fable of Brazil as a racial paradise. Due to the influence of Tannenbaum and Freyre’s work, however, a view of Brazilian slavery as comparatively benign, relative to the US, sometimes persists among educated people.

Academia in the US emphasises what is basically a Global North and Anglocentric perspective on the history of modern slavery. This global perspective has contributed to focusing on the US as the most important slave society in the Americas. In other ways, most ways, US slavery was not especially peculiar. Africans and their descendants were enslaved across the entire western hemisphere, including in present-day Chile, Canada and Bolivia. Most enslaved Africans were transported to Latin America. Historians estimate that Brazil alone imported approximately 4.8 million enslaved men, women and children, representing nearly half of the 10.5 million enslaved Africans who disembarked alive in the Americas between 1501 and 1866. These figures contrast with the estimated 388,000 enslaved Africans who disembarked in the US during the same period.

Slaves in the Streets of Rio de Janeiro (1814) by Joaquim Cândido Guillobel. All images courtesy Brasiliana Iconográfica

A Mineiro, or Native of Mine District in Brazil/A Slave going to Market (1819) by Henry Chamberlain after Joaquim Cândido Guillobel

Brazilian Slaves (1819) by Henry Chamberlain after Joaquim Cândido Guillobel

Slaves in the Streets of Rio de Janeiro (1814) by Joaquim Cândido Guillobel

The Slave Market (1821) by Henry Chamberlain after Joaquim Cândido Guillobel

Scholars of slavery know about this huge disparity between the number of Africans transported to the Americas for slavery versus how many ended up in the US, but it is not popular or common knowledge. Since the 1960s, and still today, most university programs and departments studying the history of slavery are in the US. The largest academic book industry in slavery studies is also in the US. The size and strength of the North American university system has no rival. The global visibility of the US civil rights movement, in the aftermath of the Second World War, also contributed in major ways to the extraordinary strength and vitality of scholarly research into slavery.

The Black population of Latin America hasn’t enjoyed any of these powerful cultural and intellectual institutions producing their history. During the Cold War era, brutal military dictatorships supported by the US took over Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and Chile. Under these regimes, anti-Black racism, in Brazil and other countries, couldn’t even be publicly denounced. No appeal to a right to freedom of speech existed, and Black activists who spoke out would likely go to prison.

Brazil imported 12 times more enslaved people than the US. By the mid-19th century, the US had 2.5 times more

Of course, especially in the second half of the 20th century, the soft power of the US empire brought its movies and television to the rest of the people of the Americas. Novels such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and Alex Haley’s Roots (1976) in their 1977 film and television adaptations made a very big impact around the world, including in Brazil and the rest of Latin America.

Another way in which US slavery was unusual was in the nature of population increase. Brazil imported approximately 4.8 million enslaved Africans. That’s more than 12 times the 388,000 enslaved men, women and children who disembarked from Africa alive in the region of the present-day US (some enslaved Africans also entered North America through the Caribbean). Yet in 1872, Brazil’s enslaved population was composed of approximately 1.5 million individuals, whereas even 12 years earlier, in 1860 on the eve of the Civil War, there were close to 4 million bondspeople in the US. How is it that Brazil imported so many more enslaved people than the US, yet by the mid-19th century the US had 2.5 times more?

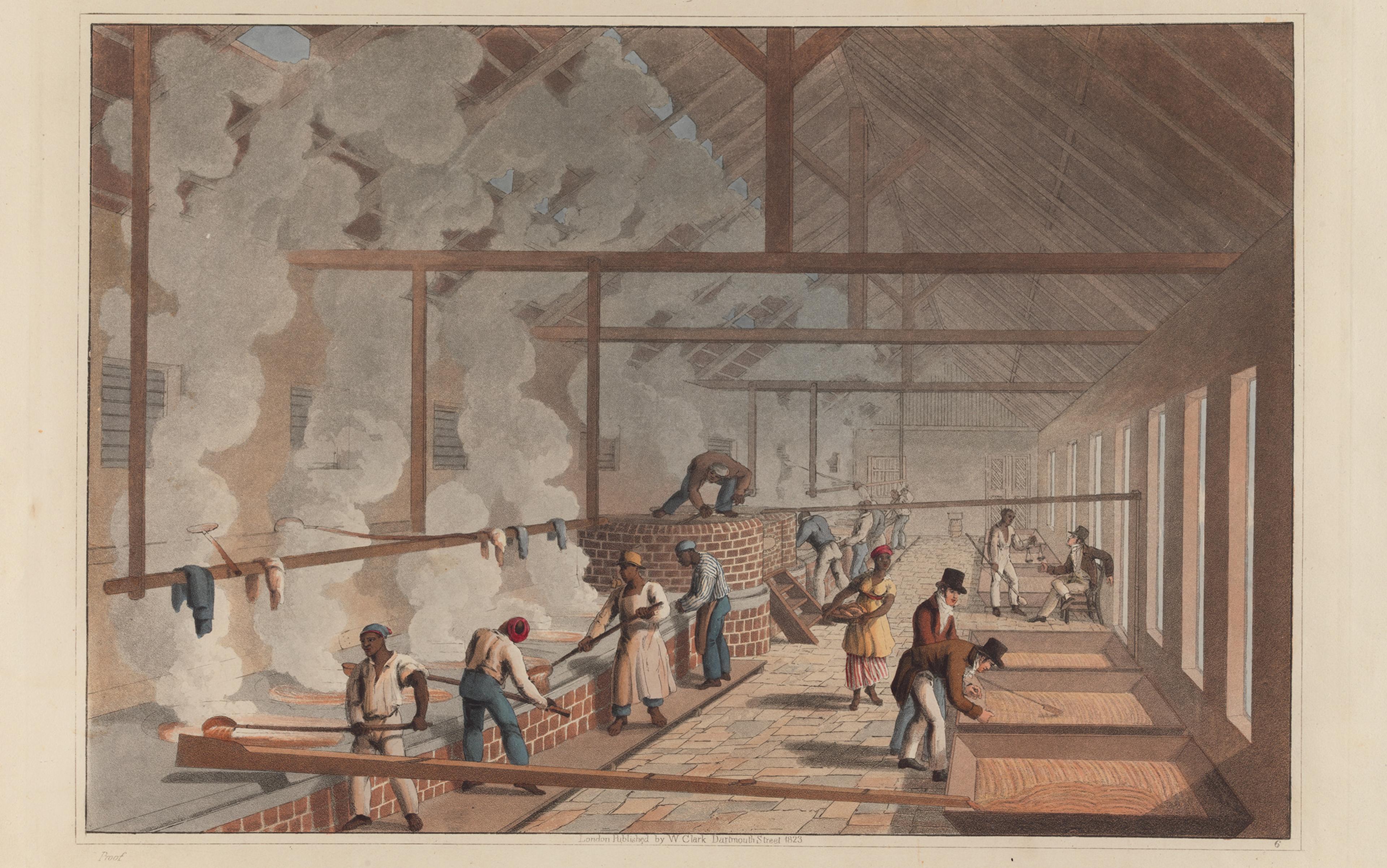

Part of the answer is that neither in the US, nor in Brazil, was slavery benign. We don’t have clear figures about slave mortality in Brazil, but as the sugar boom started in the 17th century, it’s not an exaggeration to state that enslaved people, mainly men, who worked in the northeast sugar estates rarely survived longer than seven or eight years. In Brazil, very high mortality rates and low birth rates were due in part to the gender imbalance. More male Africans were imported than females, at approximately a rate of two men to one woman. As a result, the Portuguese simply worked people to death and then continuously imported new enslaved Africans. In the US, in contrast, especially in the 19th century, the wombs of enslaved women produced the new generations of bondspeople: in other words, the population of the enslaved experienced natural growth.

Six years ago, another influential work appeared portraying the US as the centre of slavery in the Americas. The year 2019 marked the 400th anniversary of 1619, when the first documented enslaved Africans landed in the British colony of Virginia. For many decades, African Americans have embraced the year 1619 as a site of memory, in the sense established by the French historian Pierre Nora. For him, sites of memory (lieux de mémoire) exist because over time they have come to uphold a significant fragment of the past for a given community. In this way, the year 1619 came to symbolise the beginning of slavery in the US, a site of memory of slavery.

In 2019, at its 400th anniversary, 1619 received new visibility in the media, following ‘The 1619 Project’. Published in The New York Times Magazine, the project, led by the journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones, consisted of a series of essays authored by US scholars, writers and artists focusing on the present-day legacies of slavery in the US. As a result, more than before, many people started associating the year 1619 with the rise of slavery in the Americas.

In 1521, a century before 1619, enslaved people led a rebellion on a sugar estate on the island of La Española

Of course, every country is probably more interested in its history than that of others, and there’s nothing wrong in any particular instance of people focusing on whatever they wish. The problem comes if we mistake the history of the slave trade and slavery as they relate to the US for the history of slavery and the slave trade in the Americas more generally. Looking at some of the differences allows us to see how the Atlantic slave trade operated overall, and get a glimpse at life under slavery south of the US, in Brazil and in Latin America more generally, where most of the enslaved population worked and lived.

To begin, 1619 is not the beginning of slavery in the western hemisphere, only the beginning of slavery by Anglo-Americans in the present-day US. The first Africans and their descendants, either enslaved or free, arrived in the Americas more than a century earlier with the first Spanish conquerors. Already in 1521, one century before 1619, enslaved people, presumably many of whom were born in Western Africa, led a rebellion on a sugar estate on the island of La Española or Hispaniola, in today’s Dominican Republic. We know that as early as 1512, Juan Garrido, by then a free African, came to the present-day US as a member of conquistador Ponce de Léon’s expedition. As early as 1444, the Portuguese were already transporting enslaved Africans to the Iberian Peninsula, in today’s Portugal and Spain. Between 1500 and 1619, historians estimate that 369,000 enslaved Africans had already landed in the various European colonies in the Americas. This number alone is almost as high as the total number of African captives disembarked in the region of today’s US during the entire era of the Atlantic slave trade.

One of the 1619 Project’s most controversial claims was that American colonists called for the independence of the 13 colonies to protect the institution of slavery. Hannah-Jones later retracted that particular claim from the edited book that emerged from the project. Right-wing commentators attacked the project for its emphasis on slavery playing the central role in the history of the US. Challenging the US-centred perspective promoted by the 1619 Project in this polarised debate became an almost impossible task. Many participants and liberal Americans perceived criticism as supporting a campaign to minimise the centrality of slavery in the history of the US. But the 1619 Project succeeded in giving the year new meaning, especially after the summer of 2020 and the multinational protests that followed the murder of George Floyd.

The 1619 Project resonated strongly with the protests following Floyd’s murder, and reminded Americans how chattel slavery gave birth to anti-Black racism in a country still reluctant to commemorate its involvement in this atrocity. Discussion of the 1619 Project still matters because the project contributed to a new wave of US exceptionalism, reinforcing in new ways an old narrative in which the US is America, and the history of Latin America, of South America and the Caribbean, including their histories of slavery, is somehow not important or even relevant.

Brazil, along with the British colony of Jamaica and the French colony of Saint-Domingue, relied on a huge sugar plantation system worked by enslaved Africans. Their work enabled plantations of indigo, cotton and coffee, mines of gold and diamonds, jerky meat factories, and urban commerce in Rio de Janeiro, Salvador, Recife, Kingston, Le Cap and Port-au-Prince, and many other American cities across the hemisphere.

In the case of Brazil, several factors explain the huge recurrent imports of enslaved Africans. Between the late 16th century and the early 17th century, the Portuguese established the colonies of Luanda in 1575 and Benguela in 1617, in present-day Angola. These two West Central African colonial settlements respectively became the first and the third ports from which the largest number of enslaved Africans were boarded on slave ships departing to the Americas during the era of the Atlantic slave trade. They mainly went to Brazil.

Slave Being Flogged (1825) by Charles Landseer. Courtesy Brasiliana Iconográfica

Portuguese and Brazilian slave-traders relied on this advantage in early business to win a very large portion of the trade in human beings to the Americas. To sustain the burgeoning Brazilian sugarcane plantations, the Portuguese tried to enslave the Indigenous population but found it easier with a new, foreign labour force already resistant to European diseases. Two-thirds of these enslaved Africans were men, mostly captured through warfare and then transported and sold into slavery along Atlantic Africa.

San Lorenzo de los Negros obtained its independence at a time when slavery was expanding everywhere

The distance between Rio de Janeiro, the largest slave-trading port of the Americas, and Benguela and Luanda was also shorter than the distance between most West African ports and the Caribbean and North American shores. The counterclockwise sea currents and winds shortened the voyages in the South Atlantic system, again favouring the Portuguese and Brazilians in the dark commerce of the slave trade. Ocean current conditions in the southern hemisphere oriented the Portuguese and Brazilian trades, and followed a bilateral model, in which slave ships sailed from Brazil carrying goods such as alcohol and tobacco to the coasts of West Africa and West Central Africa, and then returned to Brazil transporting captive Africans. In contrast, the British and French trades in enslaved Africans relied on a triangular model. In this system, slave ships left British and French ports carrying a variety of commodities to purchase enslaved people on the coasts of West Africa. They then transported those Africans to their colonies in North America and the West Indies, from which they then carried agricultural goods to their respective European metropoles. So Brazil was directly connected to the main ports that supplied enslaved Africans to its plantations, mines and cities in a way that North America simply never was. This bilateral trade model helped make it economically feasible to maintain a steady rhythm on the sugar production, working people to death and continuously importing new enslaved Africans.

Also before 1619, starting in the late 16th century, many Africans and their descendants escaped from slavery in New World regions and formed runaway or Maroon communities. In Spanish, these settlements were referred to as palenques and cumbes, and in Portuguese as quilombos and mocambos. In 1609, a group of runaway slaves formed an important palenque near Veracruz, in present-day Mexico. After years of defending their right to self-determination against the incursions of Spanish soldiers, in around 1618, this community near Veracruz won their fight against the Spanish colonisers. In addition to getting their freedom, they were granted the land to establish San Lorenzo de los Negros, considered the first settlement of self-emancipated men and women in the Americas, today renamed after Yanga, its founder. San Lorenzo de los Negros obtained its independence including land rights at a time when, during the 17th century, slavery was expanding everywhere in the western hemisphere. The self-emancipation of San Lorenzo de los Negros came with a price, including a commitment to protect Veracruz’s coast against external attacks and return enslaved fugitives to their owners.

San Lorenzo de los Negros was not the only early runaway slave community in the Spanish Americas. Another of these communities emerged about 35 miles from Cartagena, one of the busiest slave-trading ports in the Americas, in today’s Colombia. Nearly 200,000 enslaved Africans came ashore there and lived in the palenque or Maroon community outside it. One of them was Domingo (or Benkos) Biohó, a West African-born man known by several other, closely related names. Biohó’s name referred to his likely place of birth on the Bijagós Islands in today’s Guinea-Bissau, whose men were known for being fierce warriors. Along with others from his family, Biohó may have escaped slavery as early as 1599. Together with other self-emancipated slaves, Biohó is likely one of the founders of the palenque San Basílio outside Cartagena.

In the beginning of the 17th century, the Spanish fought this palenque for years. The Maroons even signed a treaty with the Spanish, which protected their autonomy for a few years, but eventually Spain dismantled the palenque and, in 1621, Biohó was captured. The Spanish governor García Girón of Cartagena ordered his officers to hang him and dismember his body to make an example warning future rebels of the consequences.

Like other men and women who resisted slavery in Latin America, Biohó is memorialised in the village of Palenque San Basilio in today’s Mahates municipality, southeast of Cartagena. A statue representing Biohó breaking the chains honours the Black community that now lives in the village, evoking his role in the early fight against slavery in the Spanish colonies of Latin America.

Statue of Domingo (or Benkos) Biohó in Mahates, Colombia. Courtesy Wikimedia

Also in the first decades of the 17th century, Brazil witnessed the rise of the Palmares quilombo, the largest and longest-lasting runaway slave community in the Americas. Palmares is the northeastern area of the then-Portuguese colony in today’s state of Alagoas, then part of the captaincy of Pernambuco. As early as the 1640s, Palmares was already composed of nine villages. By the 1670s, scholars estimate that its population was as big as 30,000 men, women and children. Portuguese and Dutch colonists, who occupied the region between 1630 and 1654, failed to destroy the quilombo several times. In 1695, they eventually managed to crush Palmares and kill its leader, Zumbi. Today, Zumbi is commemorated all over Brazil, where statues, squares and schools are named after him. Songs, motion pictures and monuments in various Brazilian cities such as Rio de Janeiro, Brasília and Salvador pay homage to Zumbi.

Statue of Zumbi dos Palmares in Alagoas, Brazil. Courtesy Roberto Sabino/Flickr

The rise of Zumbi, a warrior who fiercely fought Portuguese and Dutch settlers, as a symbol of Black Brazilian resistance presents an illuminating contrast with commemorations and symbols of Black people in the US. Despite the globally influential US civil rights movement in the 1960s, and despite the powerful US entertainment industry, the country’s monuments to Black people are much newer than Brazil’s to Zumbi. People all over the world have seen the TV series Roots and movies such as Amistad (1997) and The Color Purple (1985; 2023), all produced by Americans in the US. But it’s also true that monuments honouring figures such as Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman or leaders of slave revolts such as Denmark Vesey are very recent initiatives, basically dating to the Barack Obama era, and largely restricted to the northern states.

Harriet Tubman Memorial Bronze, South Carolina State House. Courtesy Phil Osborn/Flickr

In Brazil, Zumbi has been honoured and celebrated as a national hero throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. The anniversary of his assassination by the Portuguese, on 20 November, is in Brazil commemorated as Black Consciousness Day, and in 2023 was established as a national holiday. Meanwhile, despite its cultural influence and prominent civil rights movement, the long history of legal segregation hindered the rise of Black rebels in the public space of the US, where African Americans remain a numerical minority. In contrast, runaway slave communities were widespread in Brazil, where today people who identify as Black and brown make up the majority of the population.

Slavery in Brazil also offered more opportunities for freedom than slavery in the US

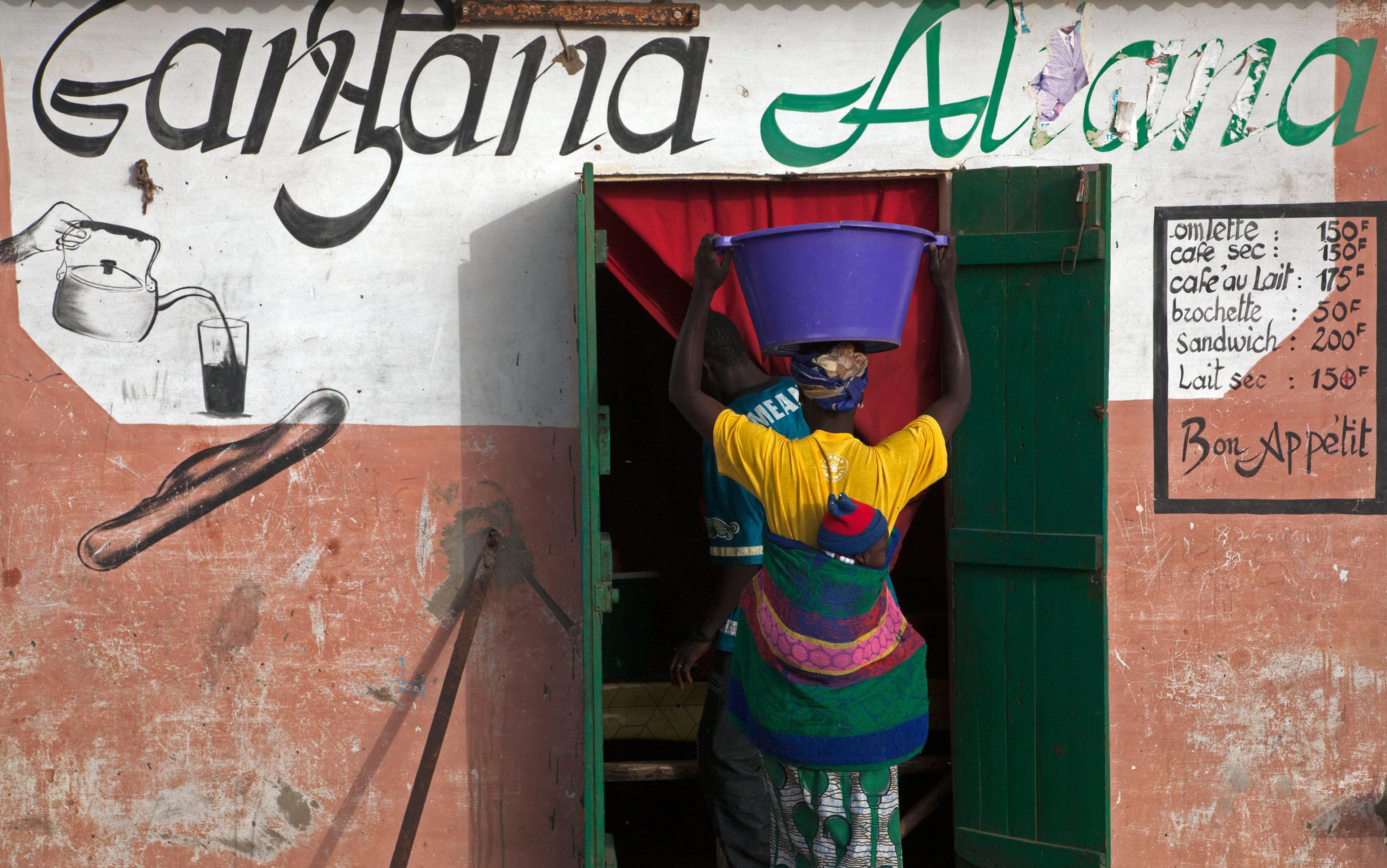

Many enslaved people lived in Brazilian cities. In those cities, bondspeople had vastly more opportunities for politics, access to litigation, and emancipation. Black and brown people, enslaved, freed or free, composed the majority of the population of Brazil’s largest cities such as Rio de Janeiro and Salvador during the entire period of slavery. Slavery existed in urban areas of the US too, but that was an exception to the 19th-century trend that saw slavery in the US growing more Southern and more rural.

Slavery in Brazil also offered more opportunities for freedom than slavery in the US. Brazilian slave-owners did not free their enslaved property out of any generosity, but because manumission, or the act of emancipating an enslaved person, was shaped by deep customs of Roman law and Catholicism. To prohibit slave-owners from emancipating their enslaved property would have required intervening civil legislation.

The historian James H Sweet and others have shown that slave owners manumitted enslaved people in Brazil mainly in the urban areas, with preference to women, children and those born in Brazil. In cities like Salvador, Recife and Rio de Janeiro, bondsmen and bondswomen performed all kinds of activities in the streets, as porters, street vendors and domestic workers. Cities gave enslaved people more opportunities to hire out their services, a practice Brazilian custom allowed, and to keep part of their income. As a result, most of these manumissions were profitable to slave-owners because enslaved people, and especially bondswomen, purchased their own freedom paying their owners their market price, and these owners could in turn then buy other slaves. More enslaved women worked in the cities, especially as street vendors and domestic workers, than men, who predominated on the agricultural estates.

Manumission, or self-purchase, existed in the US too, where it was also more likely to be available for enslaved people working in the cities or urban areas. But it was never as widespread a practice as it was in Brazil. Indeed, some of the American colonies and states actually made it illegal for slave owners to free their enslaved property. Such restrictions never existed in Brazil, or in Latin America as a whole.

Enslaved people harvesting coffee in Paraíba Valley, Brazil (c1882). Courtesy Instituto Moreira Salles

In some instances, slave-owners also emancipated their slaves for free. Though rarer, slave-owners awarded this kind of manumission by grace in their testaments, usually when older and ill. Shaped by Catholic beliefs, these manumissions were intended to be gestures of gratitude, to recognise good services. Yet, freedom was rarely immediate and often came with conditions, including sometimes requiring the manumitted slave to continue serving the owner until his or her death. In several cases, these manumissions allowed slave owners to acknowledge their relationships with bondswomen, especially those with whom they fathered enslaved children. Testaments in which slave owners freed both the enslaved women and the children fathered with them were not uncommon. Sometimes, in addition to recognising their paternity of these children, they also left them assets.

In Brazil, the story of Francisca da Silva de Oliveira, known as Chica da Silva, is perhaps the best-known instance of an enslaved woman who was freed by her owner and with whom she then maintained a long-lasting bond. The daughter of an enslaved African woman, Chica was born between 1731 and 1735 in Tejuco, in Brazil’s gold and diamond mining region in today’s state of Minas Gerais. By the early 1750s, as Inquisition officers visited Tejuco, an individual accused Chica’s owner of living in concubinage with her and another enslaved woman. The accusation was likely true, as Chica soon gave birth to her first son. Although her owner did not recognise the boy’s paternity, he freed him immediately after his Catholic baptism. In his will, he also made the child one of his heirs. In 1753, the Inquisition officers returned to Tejuco and forced Chica’s owner to sell her. In her very early 20s, Chica was sold to a Portuguese businessman and owner of a gold mine, João Fernandes de Oliveira, it seems because she was attractive. A few weeks later, on Christmas Day, João freed her. After this very early manumission, Chica and João not only continued sharing a comfortable life, but they had 13 children together. Although not legally married, after João returned to Portugal to reclaim an inheritance, Chica remained living in the couple’s large residence, administering his properties, including dozens of enslaved individuals. All her daughters and sons inherited property, whereas the males also received a university education in Portugal.

Unlike Chica in Brazil, Sally and her mother in the US were never emancipated

The assimilation of Chica and her children into the Brazilian slave-owner elite would have been unthinkable in the US. Consider the case of the Hemingses of Monticello, whose history has been extensively studied and brought into public knowledge by the historian Annette Gordon-Reed. The Hemingses are probably the most famous enslaved family in the history of the US. The matriarch Elizabeth Hemings was born in Virginia in 1735, around the same time as Chica da Silva. And, like Chica, Elizabeth’s mother was also an enslaved African woman, and her father a white man (after whom she received the last name Hemings). Elizabeth’s owner was John Wayles, the father of Martha Wayles Skelton, who went on to marry Thomas Jefferson. After John was widowed of his first wife (Martha’s mother), as well as his second and third wives, he had six children with Elizabeth Hemings. But, unlike Chica, Elizabeth was never emancipated by her owner, even though manumission was legal in Virginia from 1782 to 1806, a year before her death.

When John Wayles died in 1773, Martha Jefferson inherited Elizabeth and her 10 enslaved children, six of whom were her half-siblings. Three were freed, and three remained enslaved. None of these children received a college education. None of these children inherited property. The fate of Sally Hemings, likely the most famous of them, was very similar to that of her mother. Described as a beautiful girl of fair skin, after the marriage of her mistress Martha Jefferson, Sally became the property of Thomas Jefferson, who later impregnated her. Like her mother, Sally also had six children fathered by her owner. All six children became Jefferson’s property. Although in his late years Jefferson emancipated his male enslaved sons, he never officially manumitted his enslaved daughters. None of Jefferson’s children were his heirs. Unlike Chica in Brazil, Sally and her mother in the US, like many other enslaved women in similar positions, were never emancipated.

Richard Mentor Johnson, who served as the US vice president from 1837 to 1841, owned an enslaved woman, Julia Ann Chinn, who is referred to as his enslaved common-law wife and with whom he had two children, but who was also never emancipated.

At the same time, historians recovered many other cases of wealthy slave-owners during the 19th century who did free the enslaved women with whom they’d engaged in sexual and affective relationships. Although this contrast cannot be explained by one single factor, Catholicism allowed for recognising these bonds, especially when enslaved women bore children with their owners.

Departure for the coffee harvest by ox cart, Paraíba Valley, Brazil (c1885). Courtesy Instituto Moreira Salles

The Catholic Church did not necessarily encourage enslaved people to marry in Brazil, nor in the French and Spanish colonies of the Americas – but they were allowed to do so. Once officially married, the Church opposed the separation of married couples, even though in practice its opposition was not determinative, and separation did occur. Perhaps the most striking difference between slavery in the US and in most of the rest of the Americas – the regions colonised by the Portuguese, the French, and the Spanish – was that enslaved people in Latin America could marry free Blacks and whites. These marriages contributed to increasing the mixed-race population, who over time could distance themselves from their Black ancestors. This dissociation from Black ancestors was, and still is, possible because race in Latin America wasn’t, and still isn’t, based on the US idea of the ‘one-drop rule’ according to which any person with one Black ancestor is considered Black.

Anti-Black racism emerged in the modern world with the rise of the transatlantic slave trade and still shapes how the various societies in the Americas embrace and reckon with their past associated with slavery. But there were also clear differences on how race functioned in Latin America and in the US. For example, in Brazil, the combination of physical features and social position has been more important than African ancestry alone to determine whether a person is racialised as Black, white or in between.

It is also true that, in contrast to the US, racial segregation in Latin America was neither codified nor enforced. Despite the absence of codified segregation, racism and racial inequalities were pervasive in Latin America, especially in Brazil, where racism is a combination of colourism and classism. In other words, people of African descent with lighter skin who had opportunities to move upwards socially could easily pass as whites. Meanwhile, dark-skinned freed people who remained living in poverty were categorised as Blacks.

Race is historical, and changes from place to place and in different times

In recent years, public debates about race and racism and the legacies of slavery in Brazil are leading an increasing number of fair-skinned men and women of African descent to identify as Black or brown. This is a new development, in contrast to the US, where an individual with any African ancestors is generally identified as Black or African American, regardless of their social class or how light their skin may be. Of course in the US, more and more people have refused the dichotomy between Black and white, choosing to identify themselves as biracial. Ideas of race not only vary across the western hemisphere, they are continuing to change over time.

Nowhere in the Americas was slavery a mild institution, and throughout the western hemisphere slavery was foundational to European conquest and settlement. But nor have slavery and race in the Americas been the same everywhere.

Spain and Portugal enjoyed much longer and more direct historical relations with Africa and Africans than did Britain. So, in multiple ways, historically and later by virtue of the bilateral slave trade, Africa and Africans have arguably played a larger role in Latin America than in British North America. Geography played a part too. Tropical and subtropical agriculture was particularly deadly. Cities offered possibilities for education, knowledge and freedom. Catholicism also influenced slavery in real ways in the Spanish, Portuguese and French colonies in the New World. Understanding these differences allows us to recognise that race is historical, and changes from place to place and in different times. The US framework is not the only way the idea of race works, even in the Americas. Still today, Brazil has the largest population of African descent of all the Americas. In times when the illness of nationalism is growing across the world, and when the teaching of slavery is being attacked by the far Right and by white nationalist politicians and lawmakers, recognising the foundational role of slavery to the history of all of the Americas may help us understand one another and ourselves a little bit better.