The story began with a rumour. In 1764, a woman named Marie Aymard, who was illiterate, appeared before a notary in the small French town of Angoulême, and recounted that her late husband, a carpenter, had gone as an indentured labourer to the island of Grenada in the Antilles. He made ‘a small fortune’ while he was there, or so she had been told. She was familiar with the details: she ‘learned that her said husband had bought a certain quantity of Negroes and several mules, that he earned 24 livres per day, in addition to the 15 livres that his Negroes brought him, also per day.’ But he had died on the way home. The point of the notarial document, a power of attorney, was to find out what had happened to the fortune, and to the slaves.

There is no evidence, or none that I have been able to find, that the fortune ever existed. Marie Aymard and her children never became rich. But the story of her ‘researches’ – this was the word she used in the power of attorney – led to a network of connections to slavery and the enslaved. Even in this little inland French town, 100 kilometres from the sea, there were slaves, the owners of slaves, and the proceeds of slavery.

The employer of Marie Aymard’s husband, Jean-Alexandre Cazaud, lived a few minutes’ walk away in Angoulême, and by 1764 he had returned to the town. He even paid some of her debts, to two different families of bakers. He had been listed in a tax register, the previous year, as the owner of a sugar plantation and 50 slaves in Grenada. His father, some years earlier, had moved to Angoulême ‘from the islands’, and brought with him a slave called Jean-François-Auguste ‘with the intention of taking him back there’. Jean-François-Auguste was baptised in 1733 in the local parish church, where Marie Aymard’s children were also baptised; he was described as coming from the nation of Ouidah, in modern Benin. In 1758, ‘Claude’, from the nation of Cap Lahou, in Côte d’Ivoire, was baptised in the same church; his godfather, ‘to whom he belongs’, was Cazaud’s brother-in-law.

François Martin, aged ‘around 12’, from ‘Laguinne in Africa’ was baptised in a different parish church in Angoulême in 1775, having ‘abjured paganism’; so was ‘Jean L’Accajou’, aged 15, who was identified in the parish register as having arrived in France on the slave trade vessel La Cicogne. Jean-Alexandre Cazaud, the plantation owner, was a litigant in 1779 when his own slave, ‘Jean-Alexandre James’, escaped from ‘the most inhumane’ imprisonment, and was freed by the Admiralty court in Paris; James was severely beaten in the street in Paris, in 1780, in an attempted kidnapping and re-enslavement, and escaped only because of a ‘sort of riot’.

Cazaud’s in-laws were among the ‘capitalists’ of Angoulême, in their own self-description, and Cazaud himself was a figure of the philosophical enlightenment; as James was seeking his freedom in Paris, in 1780, Cazaud was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of London, for his work on the roots of the sugarcane. But even in Marie Aymard’s own social network in Angoulême – of small and precarious artisans – the connections to the overseas world of the colonies were omnipresent.

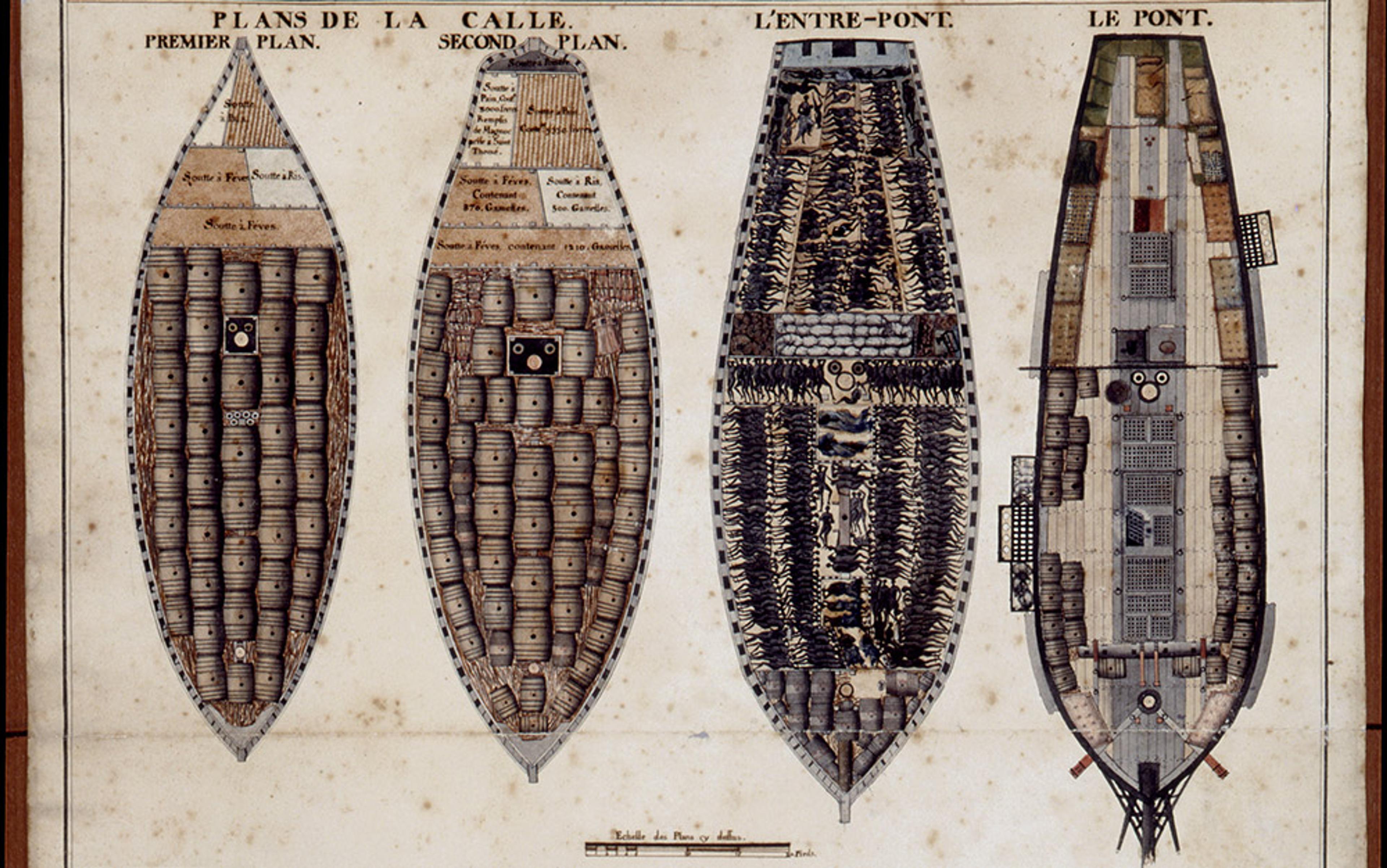

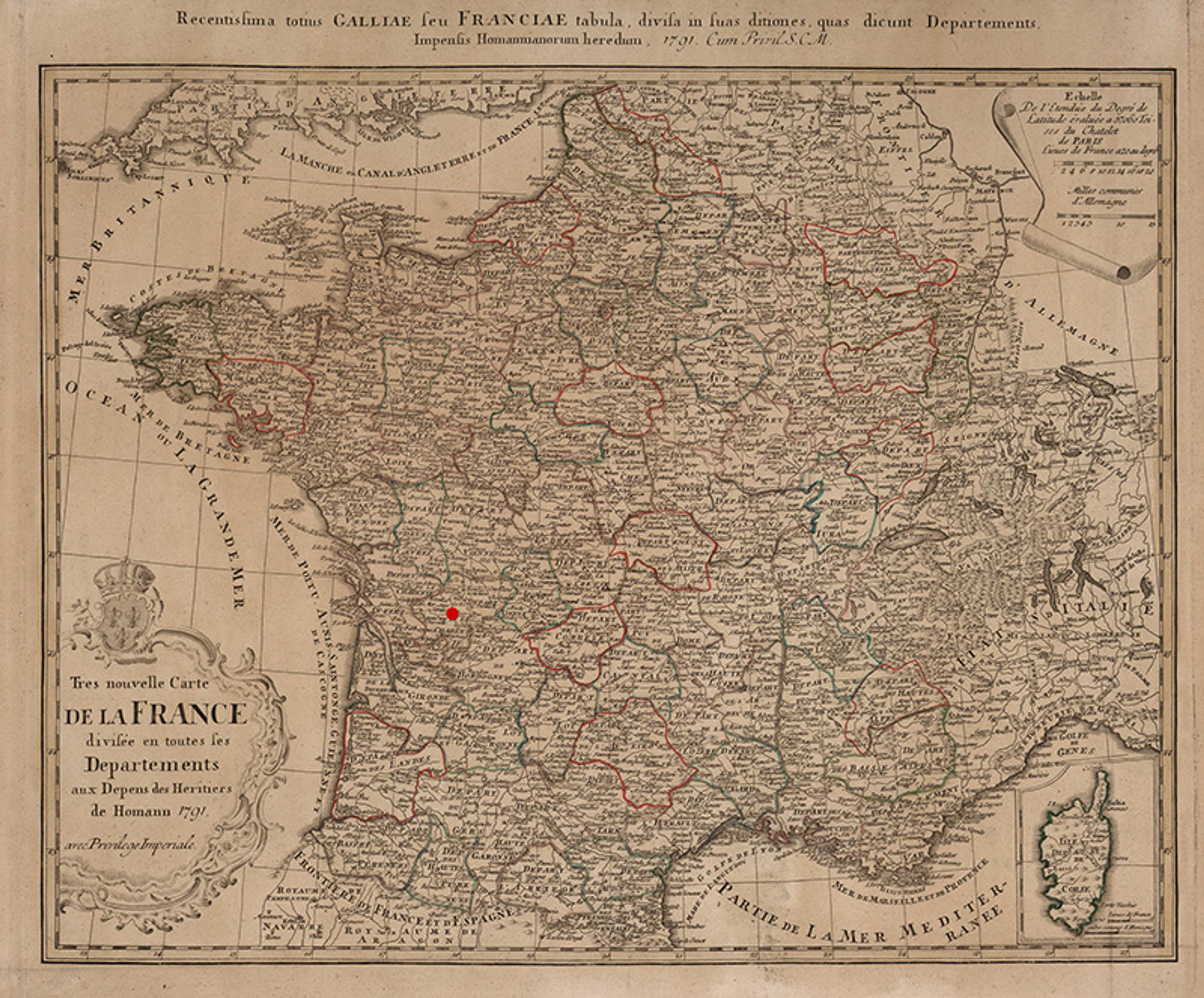

A map of France in 1791, showing the location of Angoulême (red dot). Courtesy the David Rumsey Map Collection

The other great event of 1764, in Marie Aymard’s family, was the ceremonial signing of the marriage contract of her daughter and the son of a local tailor. The tailor’s shop was at the end of the street where Cazaud lived, and most of the signatories were close neighbours or relatives of the bridegroom, from the same milieu of tailors, bakers and seamstresses. One of the signatories, the bridegroom’s cousin, a saddler called Jean Dumergue, had his own connections in the colonies. His brother was a draper in Saint-Domingue, the modern Haiti, and offered in 1769 to provide employment for the saddler’s son (‘if he knows how to write and keep accounts’). In 1770, the brother in Saint-Domingue went bankrupt; earlier in the year, he had advertised for the return of a ‘Creole negress, branded DUMERGUE above her two breasts, a dressmaker, about to give birth if she has not already done so.’

Marie Aymard’s youngest son, the brother of the bride, who also signed the marriage contract, was an apprentice watchmaker. In 1779, he too left for Saint-Domingue, where he had a shop selling coffee pots on a busy commercial corner in Cap-Français, the modern Cap-Haitien. He and his family returned to Angoulême as destitute refugees in 1795, accompanied by ‘Rosalie, a woman of colour’, and he found work, eventually, in the revolutionary administration of the town. He had once owned 15 slaves, he wrote many years later, in a petition for relief, but he was unable to prove the ‘possession of a corner of land’.

One of the leading figures in the French revolution in Angoulême, Louis Félix, had himself been born into slavery in Saint-Domingue in 1765. He was the son of ‘Elisabeth a negress slave’ and an unknown father, and was freed at birth. In Angoulême, he became a goldsmith, and married the daughter of two of the signatories of the marriage contract of Marie Aymard’s daughter. He was the public official who signed the new civil registers of the town, in the early years of the revolution, he organised searches for hidden priests, planned new, revolutionary festivals – to replace the celebrations that had been ‘created by monarchy and fanaticism’ – and was later ‘commissioner’ to the municipal administration.

There were very few individuals, in the centre of Angoulême by the 1790s, who did not live close to an ‘American’ or to someone who had come from the colonies. In a revolutionary register of property for 1791, there were 12 houses listed as belonging to Americans and one that belonged to a family who had been active in the slave trade to Borneo. The five unmarried daughters of the couple in the marriage contract were the immediate neighbours of Louis Félix, in the central square of the town. Their brother, Marie Aymard’s grandson, who married the daughter of a local apothecary, and was one of the early individuals to be divorced in Angoulême, was remarried, in 1801, to a refugee from Saint-Domingue.

He devoted painstaking efforts to proving his children’s rights to compensation for the slaves owned by their grandparents

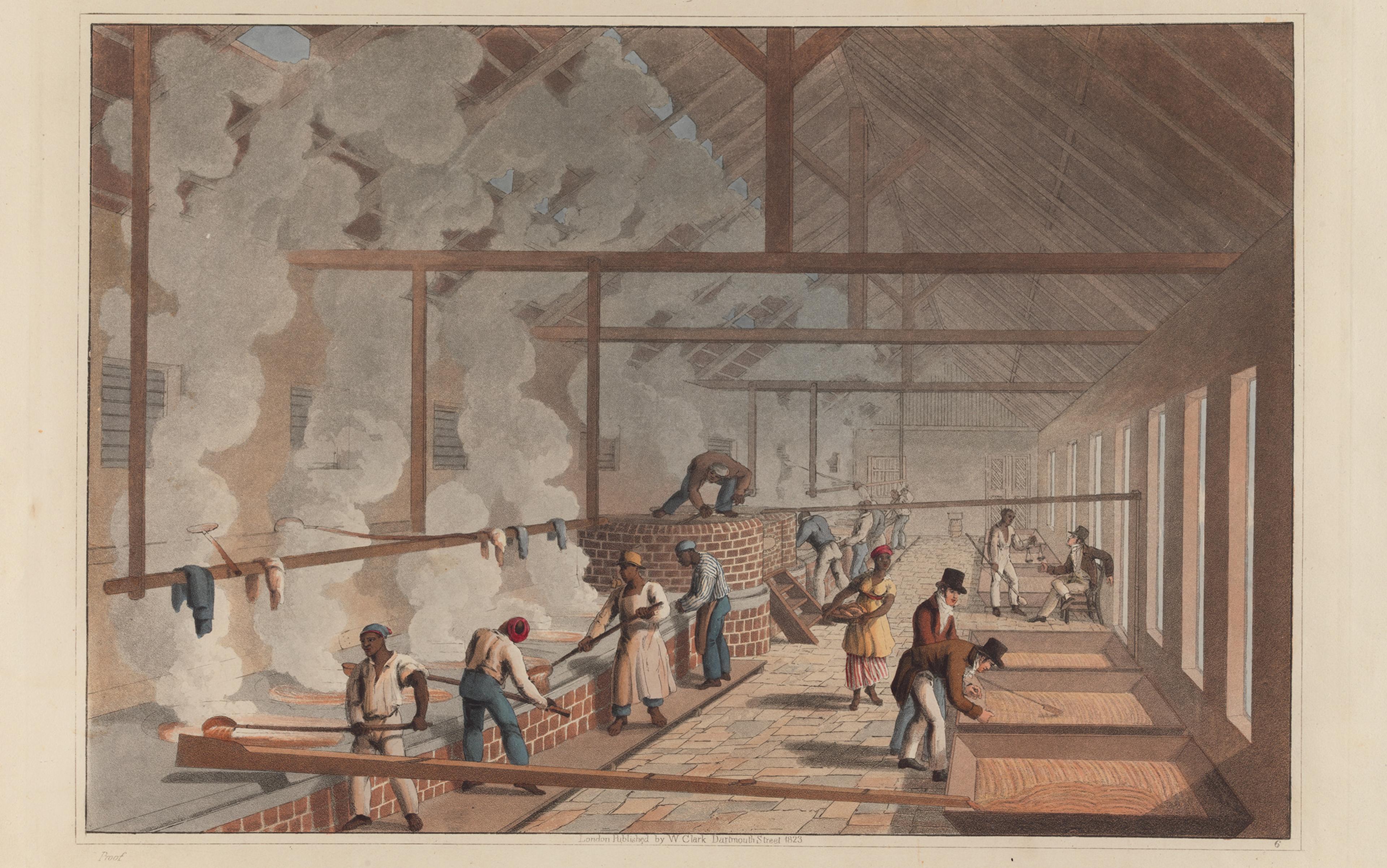

One of the Americans listed in the register for 1791, ‘M Robin the American’, had become the owner, like Marie Aymard’s daughter and son-in-law, of a ‘national’ property, confiscated from the diocese of Angoulême. He was the son of a surgeon, who had been born in Angoulême in 1750, and emigrated to the island of Saint Vincent in the Antilles, where he married an English woman, and became the manager of her family’s heavily indebted slave plantation. He then absconded – according to the irate Flemish creditor of his in-laws – with ‘40 or 50 of the best Negroes’, ‘generally all the animals’ and ‘even the copper pots and cauldrons used in the manufacture of sugar and rum’. He was imprisoned in Martinique in 1783, and was fortunate enough to find his way back to Angoulême, with his English wife; when the birth of their daughter was recorded in 1793 – in the new civil register of which Louis Félix was later the presiding official – he signed his name, ‘Robin Américain’.

The Market at Saint-Pierre, Martinique (1775) by Marius-Pierre le Masurier. Courtesy Musée Calvet, Avignon/Wikipedia

The connections to the overseas world of the colonies continued into the 19th century, and into the next generation of Marie Aymard’s family. The grandson who married the refugee from Saint-Domingue, Martial Allemand Lavigerie, moved to Bayonne, near the Spanish border. He became a sanitary inspector, the publisher of a radical newspaper, and devoted painstaking efforts, in the 1820s, to proving the rights of his children to a share of the compensation, paid by the government of Haiti, for the slaves owned by their late grandparents. In 1832, they were at last awarded a modest payment, as the heirs of a long-lost cocoa plantation. Only one of his grandsons returned to Angoulême, where he was married, in 1868, to a local girl, the great-granddaughter of the absconding Americans, the slave owners from the island of Saint Vincent.

Even in Angoulême, far from the sea, the institution of slavery was at the edge of the horizon. The restoration of the town, following the turbulence of the revolutionary years, was material as well as political. Louis Félix retired to bourgeois life, as a merchant goldsmith, and died at the age of 85, described as a ‘rentier’, or someone who lived on the returns of his investments. The town was reconstructed in the pale local stone, with a new prison, a new courthouse, several new churches, a new façade for the cathedral and a neo-medieval town hall. The architects were Paul Abadie father, and Paul Abadie son. The younger Abadie, a noted church architect, was married in Angoulême, in 1846, to a 16-year-old woman from Guadeloupe, a neighbour of Marie Aymard’s granddaughters. She too had been born into slavery, in 1830, and emancipated at the age of four. Her husband, the younger Paul Abadie, was later the architect of the basilica of the Sacré-Coeur that looms over the northern skyline of Paris.

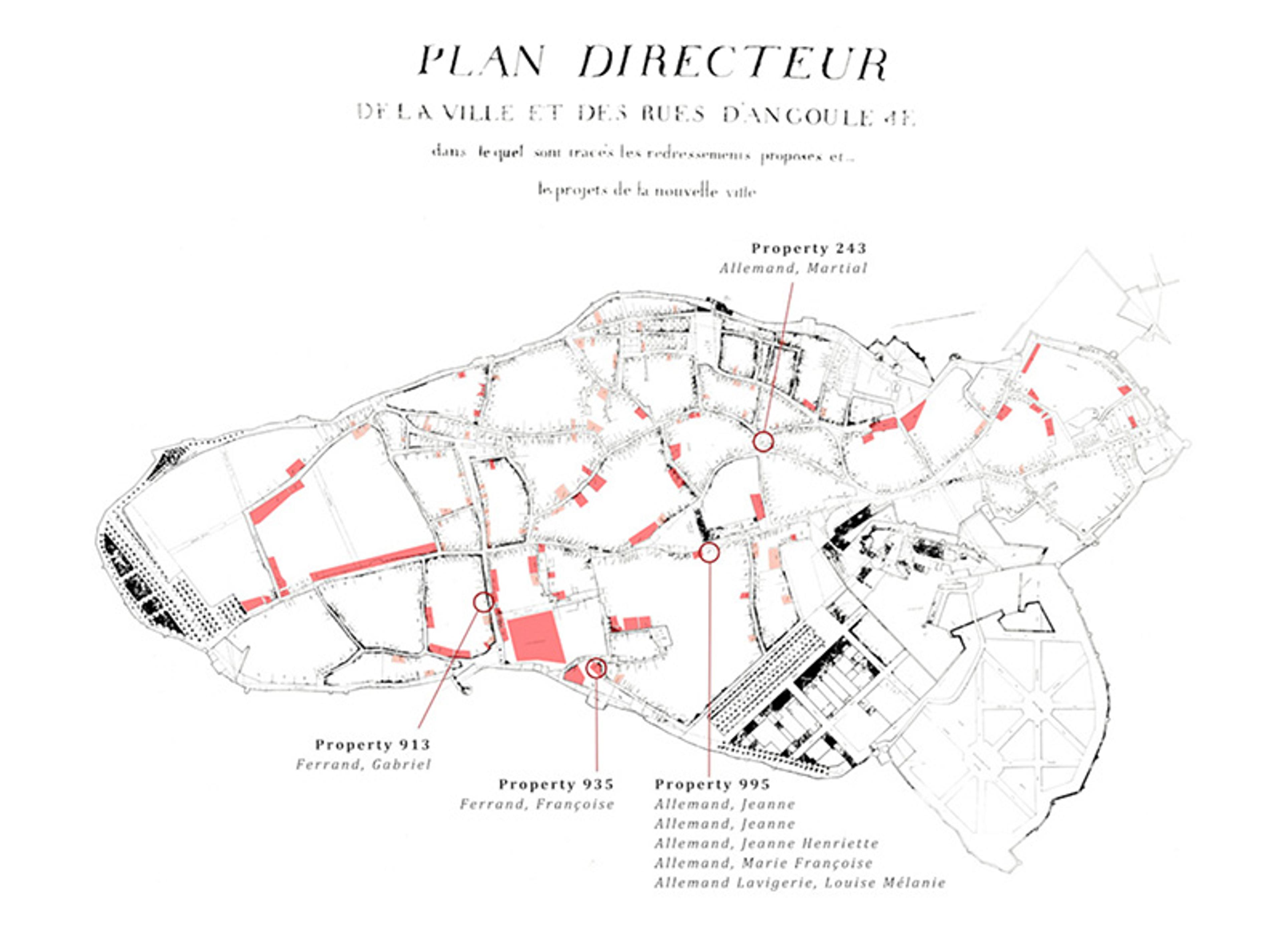

Map based on the Plan Directeur of Angoulême in 1791. The numbers on the map correspond to the numbers of the properties listed in the revolutionary register. Two of Marie Aymard’s children and several of her grandchildren appear in the register, and the properties in which they lived are indicated on the map. Courtesy Archives Municipales d’Angoulême

This history by contiguity has been an experiment in following the lives of individuals, into their social networks, the neighbourhoods in which they lived, and their family relationships. It has been based, for the most part, on the most obvious and accessible records, registers of births, marriages and deaths, and the tax rolls of who lived next to whom. Louis Félix is there in the baptismal records of Saint-Marc (in Haiti), and ‘Alida’, later Maria Alida Abadie, in the register of emancipations in Sainte-Rose (in Guadeloupe). The story of Marie Aymard’s grandson’s efforts to secure compensation for the loss of his late wife’s plantation is recounted, in part, in a marginal annotation to the register of births in Bayonne, in 1826. But the universal archives have led, along the way, to a history of the proximity of slavery, and the formerly enslaved, in ordinary life.

The Ferrands and the Allemand Lavigeries, Marie Aymard’s children and grandchildren, are not a representative family (and it is impossible to know, in any quantitative sense, what an average or representative family would even be like). There was a contagion of overseas, undoubtedly, in the family’s life over several generations. If one individual (Marie Aymard’s husband) sets off for the colonies, then it is more likely that others (her son) will do so in turn. If a cousin has a brother in the colonies (like the bankrupt merchant), then one is more likely to know of opportunities for one’s own children. There were streets in Angoulême where the Americans, and the individuals with American connections, were clustered together. But this is itself the point. There was a network of information that surrounded even these obscure individuals in the interior of France. They were informed, or misinformed, about the institution of slavery; it was part of their lives, and their expectations.

France was the leading slave-trading power in the world at the outset of the French Revolution

The history of all these individuals in a small provincial town, who are the subject of my latest book An Infinite History (2021), has been an effort, in the end, to think about slavery in the inner life of the times. I had no idea, when I became interested in Marie Aymard and her power of attorney, of the extent to which the story of her extended family, over five generations, would be an exploration of the history of slavery. An Infinite History is a micro-history, in the sense that it starts with an individual, and it is also a medium-scale and even a macro-history, in the sense that it moves outwards from the individual, by the relationship of contiguity, to her immediate family, to her acquaintances and neighbours, in the social space of Angoulême, and to her posterity over time. It has turned out, along the way, to be a history of what individuals knew about far-off slavery, and of what it meant in their lives.

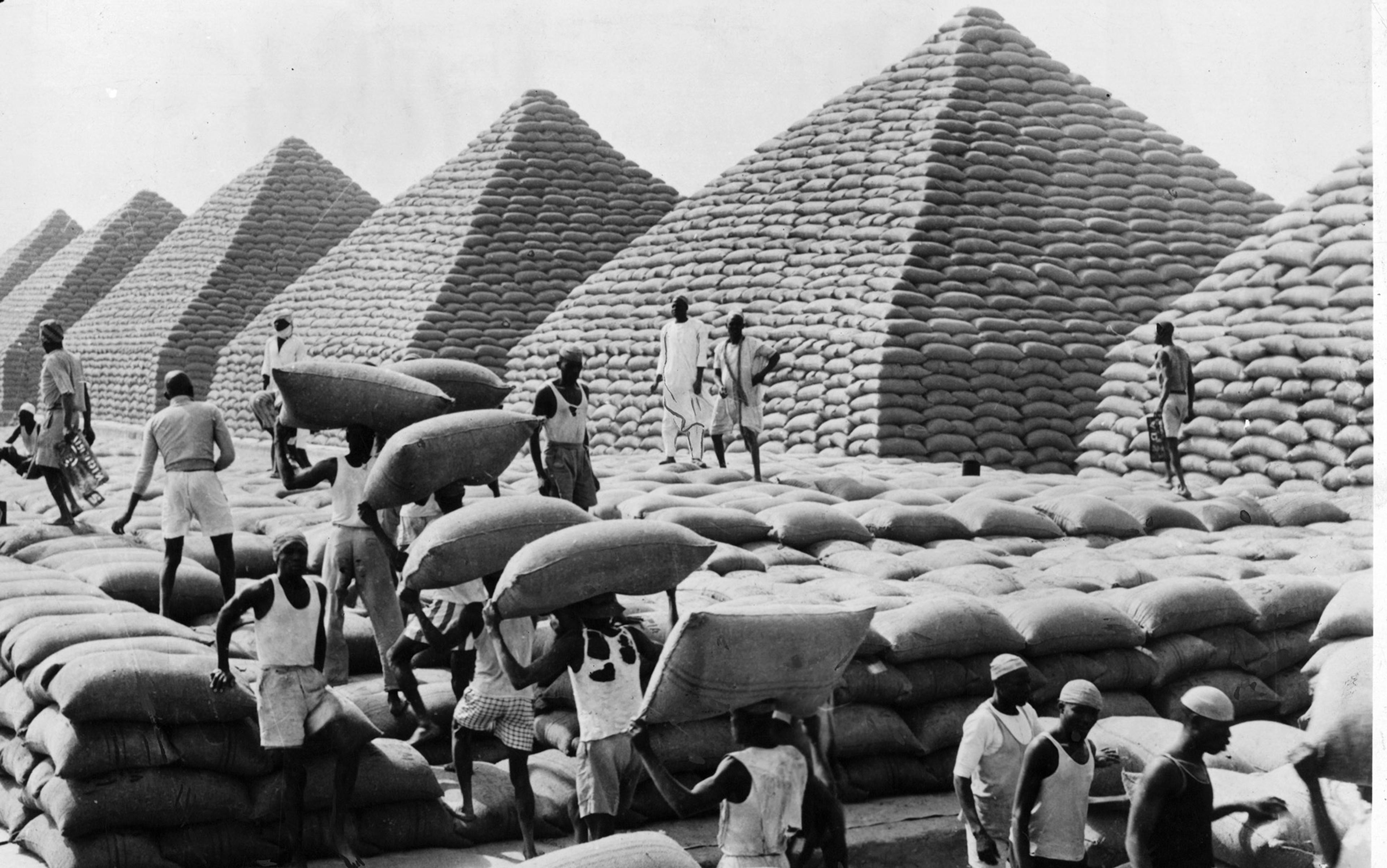

France was the leading slave-trading power in the world at the outset of the French Revolution. There were some 54,000 enslaved individuals transported in French ships in the revolutionary year of 1790. At least 460,000 individuals were living in slavery in the colony of Saint-Domingue alone; only a little fewer than the population of Paris at the time. This ‘first’ French empire, which came to an end with the Haitian revolution and the (first) abolition of slavery by the French revolutionary convention, is now the object of new interest in France. But slavery, like the compensation paid to former slave-owners over the course of the 19th century, is seen, still, as having been peripheral to ordinary life. The experience of slavery was something far away, familiar to no more than a few rich colonists, or proximate only in the busy port cities of Bordeaux and Nantes. It is this sense of distance that is called into question by the history of the Ferrands and the Allemand Lavigeries – obscure, out of sight, and far in the interior of France.

Cardinal Charles Martial Allemand Lavigerie, photographed between 1876 and 1884. Photo courtesy Wikipedia

The story of Marie Aymard’s family takes an unexpected turn, in the generation of her grandchildren’s grandchildren. The oldest grandchild of the grandson in Bayonne – by his first, local marriage in Angoulême to the daughter of the apothecary – rebelled against the (mildly) revolutionary tradition of the family. He became a priest, a bishop, archbishop of Algiers, a patron of church architects, including Paul Abadie, and eventually a cardinal. Cardinal Charles Martial Allemand Lavigerie was by the 1880s a world-famous figure, as the most prominent opponent of the trans-Saharan slave trade. The history of slavery in the American colonies, he wrote, had ‘shamed the world for three centuries by its cruelty’. But ‘the generous indignation died out’, and ‘men seemed to have forgotten that slavery still existed upon earth.’ In his new ‘crusade’, the campaign for the abolition of ‘colonial slavery’ was to be an explicit model: the ‘story of infamous scenes’, the intensity with which ‘news to do with slave ships’ was ‘reported, commented, discussed’, the novels which eventually transformed ‘European opinion’.

It is impossible, in a history that is even in part a story of ‘human consciousnesses’ – as the historian Marc Bloch wrote that all history should be – to resist other, more intimate questions. What did Cardinal Charles Lavigerie know of the long-lost cocoa plantation, and of his grandfather’s efforts to preserve the inheritance of his uncles and aunts? When he visited his grandfather, also called Martial, who had returned in retirement to Angoulême, did he hear stories of Martial’s own grandfather, and of his ‘certain quantity of Negroes’, in the far-off island of Grenada? The institution of slavery was just out of sight, in this small provincial town, and it was also close by, familiar, impossible not to see.