Listen to this essay

31 minute listen

Whatever I may be thinking of, I am always at the same time more or less aware of myself, of my personal existence. At the same time it is I who am aware; so that the total self of me, being as it were duplex, partly known and partly knower, partly object and partly subject, must have two aspects discriminated in it, of which for shortness we may call one the Me and the other the I.

– from Psychology: Briefer Course (1894) by William James

What is the self? The human condition is defined by our awareness that we are distinct from the world, that we are, in some way, the same person from day to day, even though our bodies change, and that the people around us are also selves. But we still do not really know what we are. As William James explained more than a century ago, the dual nature of the self lies at the heart of the mystery – the self is this most unusual thing, in that it is both the perceiver of itself and the content of what it perceives. Right now, for instance, ‘I’ can sense ‘my’ fingers as they type. I can also see a screen on which my words appear, and, if I choose, I can focus instead on the rims of my glasses, which move as my head moves. Interestingly, ‘my’ can refer not just to body parts but to things I wear, think or do. Although the skin is an important boundary between self and not-self, the self is more than just the physical body – it is also a set of ideas about who and what I am.

With the advent of generative artificial intelligence (genAI) that can converse fluidly in the first person, people are asking whether such AIs might someday have a sense of self. Indeed, might they have one already? (OpenAI’s GPT-5, perhaps reassuringly, says it does not.) This question is hard to answer for several reasons, but particularly because we still lack a good understanding of the human self. Significant progress is being made, however, through philosophical, psychological and neuroscientific investigations, and most recently by an approach that I and others have been exploring – the attempt to create or synthesise a sense of self in robots.

Based on what we have learned, I believe a foundational aspect of the human self is that we have physical bodies, and that our experience emerges from a fundamental distinction between what is, and what is not, a part of the ‘embodied’ me. If this is true, then a disembodied AI could never have a sense of self similar to our own. However, for robots that inhabit our physical world through a body – even one quite different to our own – the bets may be off.

To understand the motivation for building synthetic selves, we first need to explore how philosophers and scientists have sought to interrogate the human self’s nature. One part of the puzzle is that I feel as though there is a centre of experience, somewhere in my head and behind my eyes. Although it is tempting to see this as the seat of the ‘I’, this turns out to be an unhelpful idea since, as the philosopher Daniel Dennett points out in Consciousness Explained (1991), this invites an infinite regress of inner perceivers. Indeed, contemporary philosophers and neuroscientists are largely in agreement that there is no localised, unchanging, inner ‘I’ somewhere inside my head. This doesn’t mean we should abandon the idea of selves as unscientific or treat the self simply as an illusion or a purely social construct. Instead, we should find a better explanation.

If the self is not a localised inner perceiver, then what is it, and how are we to reconcile the two sides of James’s self, one of which is the perceiver of the other? One way to start to answer this question is to deconstruct the self. For instance, we can ask what are the different psychological phenomena that relate to, or demonstrate, selfhood, and where and how do they rely on specific brain regions or networks. In this way, the human self can be deconstructed, understood, and then reconstructed from its various parts.

To begin with, consider that some patients in neurological clinics have been found to have a disordered sense of body ownership, where they regard a hand or limb as not their own. Typically, these patients have been found to have endured damage to the right-hand side of the brain in a specific region around the border of the temporal and parietal cortices. Patients with schizophrenia, meanwhile, may show disorders of agency whereby thoughts or actions are experienced as being controlled by someone else. Current theories point to brain networks that predict the sensory outcomes of your own actions, suggesting that these are altered in these patients. Damage to the insular cortex, one of the oldest cortical regions that is deeply involved in interoception (processing signals from the body), can lead to a sense of emotional disconnection from the self, and is implicated in the self-related disorders of depersonalisation or derealisation. Other forms of damage, for example to the temporal and frontal cortices of the brain, can impact the experience of the self as enduring in time, or the capacity to see the world from another person’s perspective.

Our nervous and sensory systems are encapsulated within our bodies and skulls

Another approach to deconstructing the self is to ask: how do these different phenomena emerge during early childhood? Let’s begin with the infant self. Although we cannot question infants directly, developmental psychology has found ways to probe self-perception in newborns. The evidence we have so far suggests we are each born with a basic self/other distinction – knowing what is, and what is not, part of our body. We also rapidly gain an understanding of our own agency, and when we have caused something to happen. However, the experience of the self as persisting in time is something that emerges much more gradually, as is our ability to conceive of others as having selves. Indeed, it may not be until age four or five that children have a sense of self that begins to resemble what we experience as adults.

Of the many important changes during development, the acquisition of language and of culture are central in shaping our adult experience of self. Indeed, at the conceptual level, the mature sense of self derives in part from ideas and beliefs about ourselves that we abstract from memory or acquire from others. This ‘narrative’ aspect of the self is the one on which notions of human identity typically depend, and it also emerges in the story we tell ourselves and others about who we are.

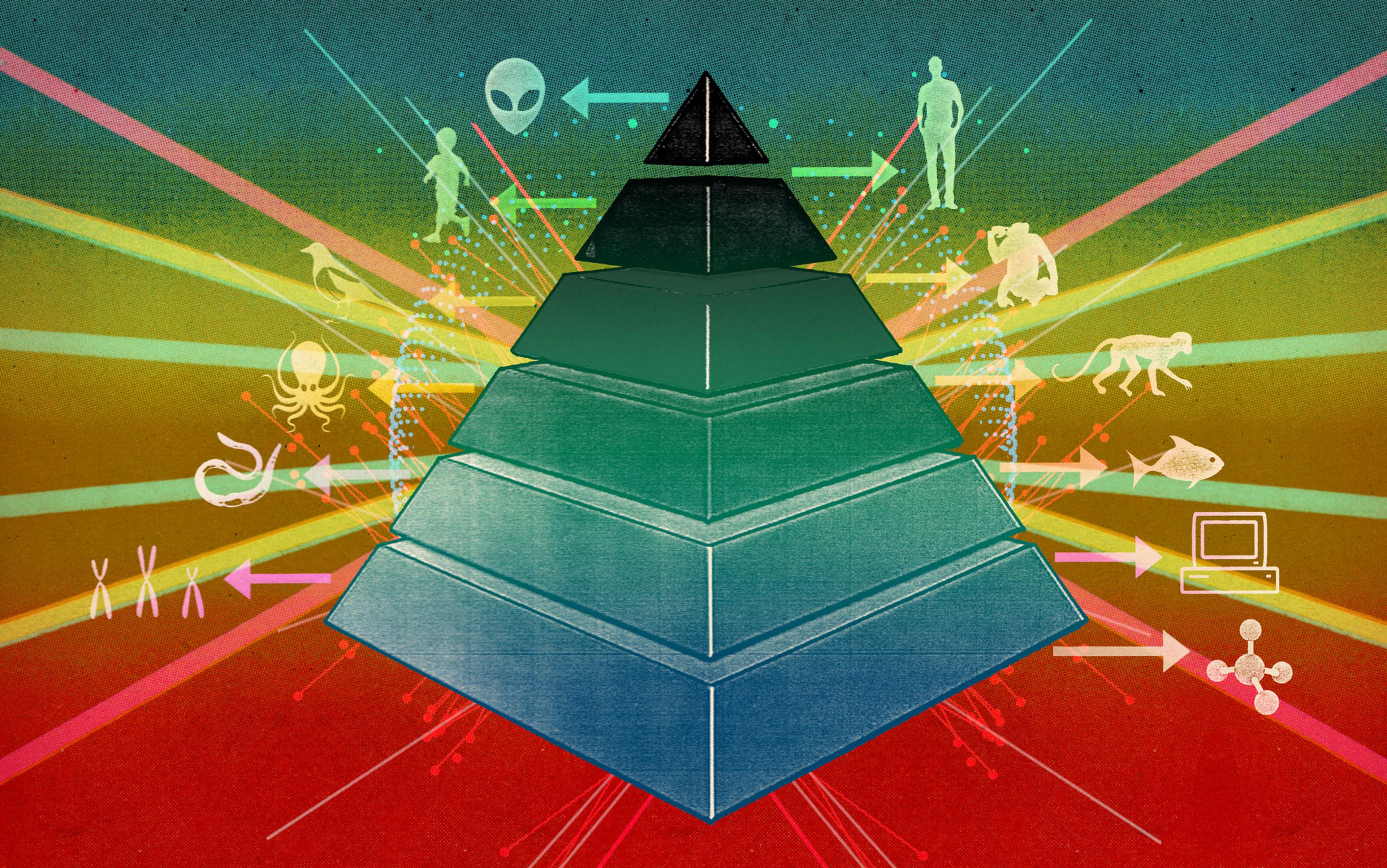

That there are different, and perhaps simpler, experiences of self in infancy, has led philosophers, including Dennett and Shaun Gallagher, to define a ‘minimal self’. This involves just the senses related to body ownership and agency, with no awareness of the self as persisting in time, or as something that can be thought about (self-reflection). The neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp and the neurologist Antonio Damasio each suggest that something similar to this minimal self arises from activity in sub-cortical areas of the human brain. These are some of the earliest brain regions to mature in newborns. These are also parts of the brain that have changed less in evolution than the cerebral cortices, and so are similar in other vertebrate animals. In other words, other animals with a backbone also likely have (at least) a minimal sense of self.

So why did something like the minimal self evolve in our animal ancestors? Because, by structuring and organising experience, it promotes survival. First, by separating sensory signals that relate to the body from those that do not, an animal can better distinguish which parts of the physical world need to be protected and defended. To consider just one critical consequence, this prevents a hungry animal from trying to eat itself. Second, by identifying whether sensory signals are related to its own internally generated actions, an animal can distinguish events it has caused from those that are happening around it. For instance, an electric fish can detect whether a small disturbance in the electric field surrounding its body was generated by the flick of its own tail or by the movements of a prey animal. This allows the fish to distinguish a feeding opportunity from routine swimming. Partitioning the sensory world in this way – creating a self/other distinction – is surely a useful starting point for succeeding in life as an embodied intelligence.

According to this view, the emergence of the full human self, which builds on this minimal foundation, is a consequence of our bounded nature. More specifically, I would argue that our human sense of self takes the form that it does largely because we, like other animals, are physically enclosed by our body surfaces, and our nervous and sensory systems are encapsulated within our bodies and skulls. In humans, this minimal self gives us our primary experience of owning our own bodies and of having agency over our actions.

To explore this further, it will help to be a bit more specific about what I understand the self to be. For Dennett, writing in ‘The Origin of Selves’ (1989), the minimal self is an ‘organisation which tends to distinguish, control and preserve parts of the world’. This makes the self a virtual entity even though it is realised through physical processes in the body and brain. Following the philosopher Thomas Metzinger in Being No One (2003), we might also describe the human self as a mental model – a virtual structure that captures, organises and manipulates percepts, memories, feelings and facts related to the embodied ‘me’. This self-model is instantiated by a cluster of brain networks, closely integrated with other bodily processes, and becomes active during wakefulness but is inactive during deep sleep or general anaesthesia.

The synthetic approach can help us tackle problems that have vexed philosophers and neuroscientists

As we have seen, there are multiple brain substrates involved in the self’s construction, some early maturing, some partially overlapping. These different networks interact and integrate to provide a coherent experience of self – something that both evolutionary biology and psychological science can help us understand. Various forms of self-disintegration are also possible due to different neuropsychological conditions – which studies of neurodiversity can illuminate.

However, I believe it is also useful to explore what I call the synthetic approach, that is, to understand the self by trying to build one. The hypothesis that the self is virtual – a mental model – also lends itself to this strategy.

The synthetic approach can help us tackle various problems that have vexed philosophers and neuroscientists. Although the self is not itself a physical entity, to construct a sense of self that might be similar to our own, I believe we require, at minimum, an artificial system that has a physical body, that can sense the world directly, and that can act. In other words, a robot.

Let’s start with the challenge of distinguishing ‘me’ from ‘not-me’, a capacity that is central to constructing the minimal self and that relies on being able to sense both the body and the world. Most robots today have sensory capacities that allow them to internally sense their own hardware. Particularly commonplace is the capacity to detect the positions of body parts and joints, and measure the velocities of the motors that move them. This is similar to the human internal sensory capacity we call proprioception. Some robots also have tactile sensors on their surfaces that provide a form of artificial skin, allowing them to directly sense contact with the world at their boundaries. Robots with distal sensors, such as cameras and microphones, immediately have a ‘point of view’ at least in the most literal sense of the phrase. That is, there is a position and pose in the world that they occupy at any moment that defines and limits what they can sense. When the robot is occupying that position, no one and nothing else can.

These sensory capacities, combined with appropriate processing, can allow robots to begin to make sense of their own embodiment as a first step towards building a self/other distinction. Indeed, many labs have explored how a robot can construct a model of its own morphology (the shape and structure of its body) simply by generating random movements – termed ‘motor babbling’. As an example, the roboticist Josh Bongard and colleagues used genetic algorithms – inspired by biological evolution – to allow a star-shaped robot to learn the configuration of its legs. The robot was then able to discover forms of forward locomotion. Other robots, equipped with jointed arms and hand-like grippers, have used neural network learning algorithms to discover their arm and hand configurations, and apply this knowledge to perform tasks such as reaching for and grasping objects.

A composite image of a newly developed robot standing over ‘water’ in which the machine is mirrored as a colourful block figure. By conjuring and using such a simple model of itself, the device can adapt to damage more readily than ordinary robots do. Courtesy Bongard et al, photo by Viktor Zykov (Lipson Lab)

Babies also perform motor babbling, both in the womb and as young infants, before learning to perform more goal-directed reaching movements. Before birth, a baby will use its sense of touch to discover that touching itself provides a different experience to touching the non-self. Specifically, self-touch provides a double touch sensation both on the fingers and on the body. As a result of this experience in the womb, the newborn is already able to make some basic distinctions between self and non-self. For instance, orienting towards a touch on the cheek but not when the contact is made by their own hand. Double touch, as a means of distinguishing self from other, has also been explored in humanoid robots, to allow robots to understand the extent and limits of their embodiment.

They trained the robot, using motor babbling, to construct a representation of its own hand

Another way that humans and robots can learn the difference between self and other is through senses such as vision and hearing. For instance, young infants typically spend considerable time looking at their own hands. In my own lab, we have performed soon-to-be-published experiments with a simulated robot showing that directing attention to the hands and arms, while they are moving, can allow learning of a visual self/other distinction. Specifically, correlations between internal proprioceptive signals, and changes in the stream of camera images due to self-movement, allow the robot to segment their visual world into parts that are related to the self (moving body parts) and everything else (the world).

A simulated robot observing its own hand movements as a means to learn about its own body. Image provided by the author

In the human self, sensory information also underlies its capacity to adapt to change. A now-classic demonstration of this flexibility is the rubber hand illusion (RHI). In a typical experiment, people experience ownership of an artificial hand when they observe it being stroked with a brush in synchrony with brushstrokes made on their own (concealed) hand. Inspired by this, the cognitive roboticist Yuxuan Zhao and colleagues integrated a simplified model of some of the cortical networks involved in human body representation, and that are implicated in the RHI, into the control system of the iCub humanoid. They then trained the robot, using motor babbling, to construct a representation of its own hand. Next, the robot was exposed to a variant of the RHI that has been extensively used with humans and monkeys. Both the robot’s behaviour, and changes in the firing rates of some model neurons, matched those observed in experiments. These results showed that the robot adapted its internal body model to include the new hand, validating the underlying theory of how body ownership is instantiated in the brain.

Building synthetic selves can also help us understand the sense of agency, another key characteristic of the minimal self. One well-known theory of agency, known as the comparator model, argues that the brain predicts the sensory consequences of self-generated actions. For instance, when you walk, your brain predicts the sound of your own footsteps, and you feel agency over those sounds. Meanwhile, if you hear footsteps when standing still, the sensory events will be experienced as externally caused. Imbalances in the brain systems involved in making and matching such predictions could explain some disturbances of agency seen in people with schizophrenia, who sometimes experience their actions or thoughts as having been authored by someone else.

To test theories of agency, in our research with a motor-babbling robot, we added a second layer to our self-model that allows the robot to predict how the visual world will evolve in the near future. The cognitive roboticist Pablo Lanillos and colleagues have gone a step further. In their study, a humanoid robot used a predictive learning algorithm, based on the comparator model, to distinguish its own mirror reflection from that of an identical robot. Self-recognition was possible because the movements of the robot’s own mirror image were predictable, based on its internal motor signals, while those of the other robot were not. Interestingly, these researchers had to go beyond the core comparator theory to make this work, demonstrating the value of robotics in assessing the sufficiency of theoretical ideas about the self.

The focus of the studies I have described is typically on one behavioural capacity or benchmark, and these robotic systems (predictably) fail when challenged with something beyond that. However, if we assembled and integrated these different ways of body-mapping and sensing, we could construct something close to what philosophers and scientists have described as a minimal self. This could help us to better understand the experience of self in human infants, and perhaps in other animals.

But what about the adult sense of self with which most readers of this article will be more familiar? Again, by decomposing the self into parts, we can begin to see how each of the component systems can be constructed and then brought together.

One phenomenon that particularly interests me is our capacity to conceive of ourselves as persisting in time – that we have the experience of being the same person yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Psychologists, such as Endel Tulving, have suggested that this aspect of self builds on our capacity for episodic memory (memory for specific events), and on our human ability to mentally ‘time travel’ back to the past or to imagine the future. Brain-imaging studies show that both of these rely on networks that involve the hippocampal system, one of the more slowly maturing components of the human forebrain. Developmental studies show that, while the younger child, from around age two, has some understanding of past and future, a more adult-like idea of time as linear and measurable (with clocks and calendars), emerges only when children reach school age. It is likely that this experience of the self as a persistent entity arises alongside the child’s broader understanding of time itself.

Robots, unlike humans, have built-in clocks and calendars and can store everything that happens, but more is needed for a human-like sense of the persistent self. For instance, memory is, in part, a retrieval problem. How do you recollect information about the past that is specifically relevant to the present or future? Research in my lab and several others has used AI generative models to begin to construct something like human episodic memory for robots. Rather than retrieve stored episodes directly, these models, like human memory, actively reconstruct past events based on partial cues, quickly retrieving information needed to understand the current scene. The same system, probed in a different way, can also construct possible future scenarios. Connecting these capacities to a minimal self-model could allow the construction of a robot self that is able to revisit its own past and conceive of the future.

A humanoid robot can map a simplified model of its own human-like morphology onto a person

Robots can also help us explore another aspect of the adult self – the sense of ‘me’ as different to ‘you’. You and I are both bounded, which means that we cannot directly share each other’s experience, although we can bear witness to it, and even imagine it based on our own. Evidence from human development demonstrates that we gain these capacities relatively gradually. Indeed, it is not until we are three or four years old that we can begin to think of the world from another person’s point of view. Although we are born with a strong predisposition to bond with social others, particularly our immediate family, the skills that allow us to understand them as other selves rely on various building blocks that we assemble during infancy and childhood. These include the capacity to learn by imitation and to have joint attention with another person – both of which have been extensively researched in robotics.

In psychology, the ability to see the world from another person’s perspective has been investigated using ‘theory of mind’ tasks, and these have now been used as benchmarks in robot models. Parts of the brain involved in the representation of your own body are also used in thinking about the actions of others, which is sometimes referred to as the ‘mirror neuron’ system. The roboticist Yiannis Demiris and colleagues have shown that a humanoid robot can map a simplified model of its own human-like morphology, something similar to a stick figure, onto a person in a shared task such as playing a game. This ability can then be used to better understand the actions of the human partner and can support other capacities such as imitation learning.

A key feature of the human self-model is that it integrates and pulls together all of these different aspects of self. How does this happen? The many different neural systems related to the self are coordinated by what we refer to as a ‘cognitive architecture’, the large-scale functional organisation of brain systems, and something that for humans remains poorly understood. In artificial intelligence, we are currently able to replicate many individual capacities of the human brain, but putting this together into integrated, reliable real-time synthetic systems remains a real challenge.

One of the keys to unlocking the human cognitive architecture may be its ‘layered’ nature. Specifically, as noted earlier, in several domains of the self, core capabilities are supported by brain systems that are available from birth; these then ‘scaffold’ the construction of more sophisticated representations of the self in the slowly developing cerebral cortices. A further way to think of layered control in the brain is as a hierarchy of predictive models. Here, successively higher-level models try to predict the inputs they will receive from the layer below and receive signals that allow them to improve their predictions. At the bottom of the hierarchy, low-level perceptual systems receive sensory signals from the body and the world. At the top, we would find constructs that are abstracted from specific sensory modalities and from the moment-to-moment vagaries of real-world interaction. This is where we could expect to find a stable set of ideas that form the more conceptual aspects of the self.

A further important source of this self-concept is culture and language. As soon as we can talk, we begin to acquire our cultural or ‘folk’ notions of what the self is and, particularly, about what kind person we are. Another source is autobiographical memory. Although the capacity to remember individual scenes from our past may be present from around age two, the ability to structure these memories into ‘stories’ about the self typically does not emerge until we are four or five years old. By this age, we usually have a good mastery of language and are already deeply embedded in cultural ways of thinking about the self, including through storytelling, and so we begin constructing stories of our own. The computer scientist Peter Dominey and colleagues looked at the construction of narratives for robots tasked with retelling what happened during social interactions. Instead of being given abstract rules, the robot learned language by connecting words and grammatical structures to its sensory experiences – such as position, motion or contact – mirroring child development. The resulting narratives summarised the robot’s experience and made it communicable, however, they also shaped the internal representations that the robot used to conceptualise events, just as natural language shapes our human experience of the world.

The iCub robot interacting with a researcher. Credit SPECS lab/Paul Verschure

By now, I hope I have persuaded you that we can use synthetic modelling – robotics – to gain insight into various aspects of the human self. However, I am sure that some readers will be sceptical. Particularly, although it might seem plausible that robots could meet some behavioural benchmarks related to the self, this (arguably) could be taking place without there being any robot subjectivity at all. Are we just modelling William James’s ‘me’ and missing out the ‘I’ altogether? More broadly, does this kind of analysis simply overlook something crucial about the experiential nature of the human self?

The neuroscientist Anil Seth certainly thinks so. For Seth, quoting Thomas Nagel, the fact that there is ‘something that it is like’ to be a human, or indeed an animal, relies on something about our biological nature that cannot be captured in a synthetic device. Seth points to many features of biological systems that are not shared with robots. His list includes phenomena at multiple different levels of description and organisation, from electromagnetism in mitochondria (sub-cellular energy systems) and the biochemical substrates of neural computation through to metabolism, autopoiesis (that biological systems are self-maintaining) and the struggle to survive. Biological selves certainly have all of these things, and robots do not, but their causal connection to our subjective experience of selfhood is not clear.

An alternative way to think about experience might obviate the need for this kind of biological foundationalism. The psychologist J Kevin O’Regan argues in Why Red Doesn’t Sound Like a Bell (2011) that the roots of experience are not just in the brain but in the interactions of bodies and brains with the environment – that the feelings that constitute our experience correspond to the unique ‘sensorimotor contingencies’ that our actions bring about. For example, the feel of a soft object, such as a sponge, lies in the ‘squishing’ action through which the object deforms when we compress it between our fingers. By this measure, any entity capable of generating sensorimotor contingencies through embodied interaction with the world, and this would certainly include robots (given the right kind of sensors, actuators and so on), could have experience.

It starts as a sense of having a boundary, and then of having agency, leading to a self/other distinction

The sensorimotor contingency account of experience does, however, exclude some kinds of synthetic entities from having subjectivity – disembodied genAIs such as today’s large language models (LLMs). These models are very effective at using subjective language, so it is tempting to view them as having experience. However, it is probably more accurate, as the cognitive roboticist Murray Shanahan and colleagues have argued, to see LLMs as ‘role playing’ subjective experience, through their capacity to emulate and re-purpose the human linguistic output they have trained on. This critique can also be extended to most current social robots. These increasingly use LLMs for social interaction in a manner that is often far beyond their capabilities for scene- and self-understanding. In reality, these robots are not much closer to having a sense of self than a smart speaker.

This leaves us with a difficult problem. How can we know when another entity has subjective experience of not? For Seth, even more sophisticated scientific benchmarks such as the capacity to experience illusions may not be enough (recall, a robot has been shown to be susceptible to the rubber hand illusion). I am reminded of the film Blade Runner (1982) in which the protagonist Rick Deckard is tasked with distinguishing replicants (synthetic humans) from natural ones using the ‘Voight-Kampff test’. This test involved asking emotionally provocative questions and looking for subtle changes in behaviour, including physiological responses such as blushing and pupil dilation. The Voight-Kampff test is fictional, of course, and the diversity of human selves is such that some of us might not pass such a test, even if it did exist.

Leaving aside the difficult problem of experience, I believe that the synthetic approach, and its realisation through robotics, has much to recommend it in terms of helping us to understand the human sense of self. By bridging psychological, neuroscientific and computational research, we can begin to construct a theory of self as a virtual structure, which starts as a sense of having a boundary, and then of having agency, leading to an initial self/other distinction. To this is gradually added an increasing awareness of persistence in time brought about by episodic memory and the capacity for mental time-travel. The ability to reflect on all of this – that is, to conceive of this bounded, persistent and experiencing entity as a specific person with a history, likes and dislikes etc – comes later, and as you share your thoughts and ideas about yourself with others.

While LLMs may have no sense of self, their capacity to use self-referential language so fluently does provide a further insight – there may be no strong distinction between perceiver and what is perceived, beyond that which is constructed in language. In a sense, and like LLMs, we are also skilled role-players, constructing, maintaining and performing an idea of ourselves. However, unlike disembodied AIs, we are ultimately able to ground these conceptual and narrative aspects of our selves through our unmediated and entangled engagement with our bodies and the world.