The brain is a machine: a device that processes information. That’s according to the last 100 years of neuroscience. And yet, somehow, it also has a subjective experience of at least some of that information. Whether we’re talking about the thoughts and memories swirling around on the inside, or awareness of the stuff entering through the senses, somehow the brain experiences its own data. It has consciousness. How can that be?

That question has been called the ‘hard problem’ of consciousness, where ‘hard’ is a euphemism for ‘impossible’. For decades, it was a disreputable topic among scientists: if you can’t study it or understand it or engineer it, then it isn’t science. On that view, neuroscientists should stick to the mechanics of how information is processed in the brain, not the spooky feeling that comes along with the information. And yet, one can’t deny that the phenomenon exists. What exactly is this consciousness stuff?

Here’s a more pointed way to pose the question: can we build it? Artificial intelligence is growing more intelligent every year, but we’ve never given our machines consciousness. People once thought that if you made a computer complicated enough it would just sort of ‘wake up’ on its own. But that hasn’t panned out (so far as anyone knows). Apparently, the vital spark has to be deliberately designed into the machine. And so the race is on to figure out what exactly consciousness is and how to build it.

I’ve made my own entry into that race, a framework for understanding consciousness called the Attention Schema theory. The theory suggests that consciousness is no bizarre byproduct – it’s a tool for regulating information in the brain. And it’s not as mysterious as most people think. As ambitious as it sounds, I believe we’re close to understanding consciousness well enough to build it.

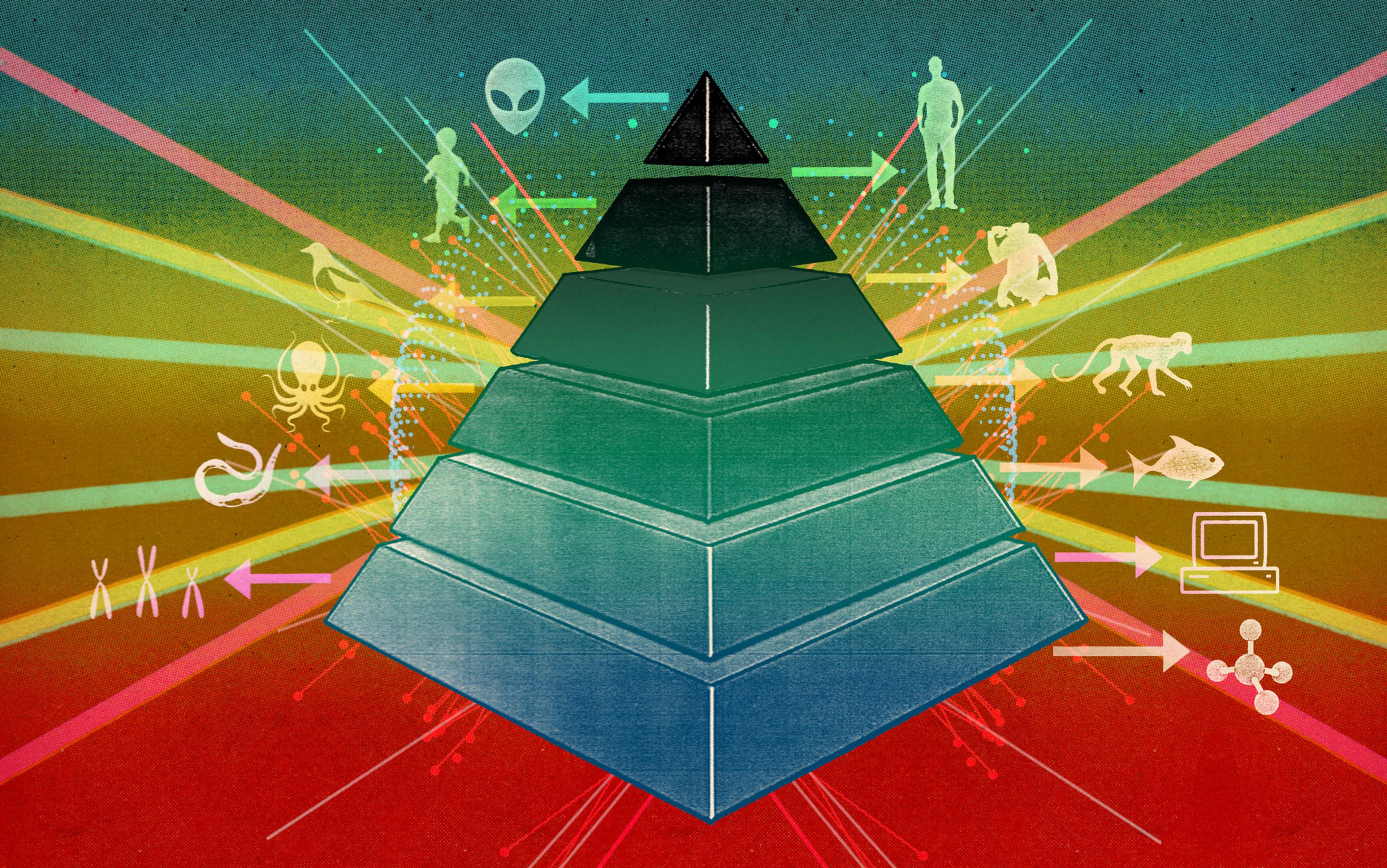

In this article I’ll conduct a thought experiment. Let’s see if we can construct an artificial brain, piece by hypothetical piece, and make it conscious. The task could be slow and each step might seem incremental, but with a systematic approach we could find a path that engineers can follow.

Imagine a robot equipped with camera eyes. Let’s pick something mundane for it to look at – a tennis ball. If we can build a brain to be conscious of a tennis ball – just that – then we’ll have made the essential leap.

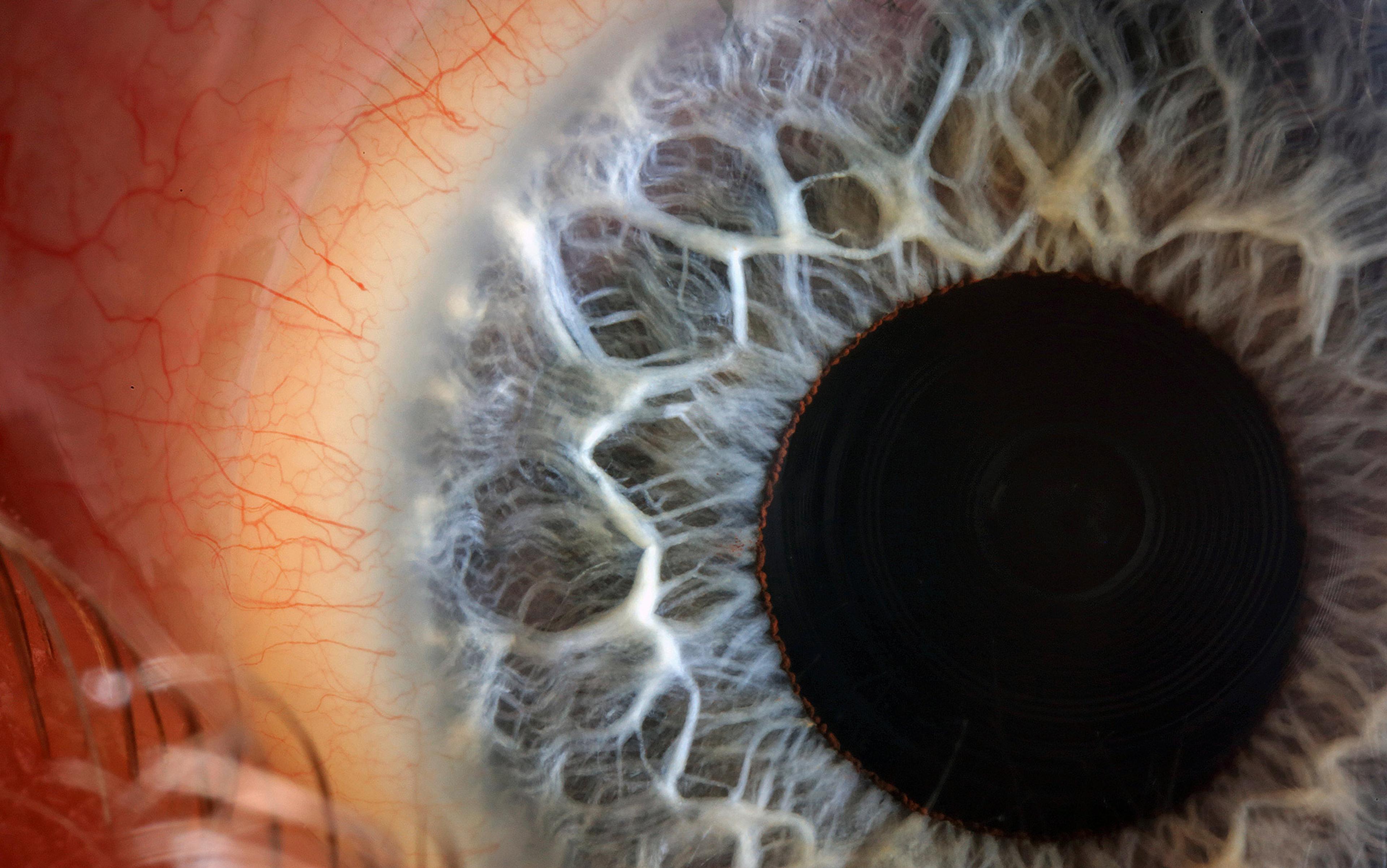

What information should be in our build-a-brain to start with? Clearly, information about the ball. Light enters the eye and is translated into signals. The brain processes those signals and builds up a description of the ball. Of course, I don’t mean literally a picture of a ball in the head. I mean the brain constructs information such as colour, shape, size and location. It constructs something like a dossier, a dataset that’s constantly revised as new signals come in. This is sometimes called an internal model.

In the real brain, an internal model is always inaccurate – it’s schematic – and that inaccuracy is important. It would be a waste of energy and computing resources for the brain to construct a detailed, scientifically accurate description of the ball. So it cuts corners. Colour is a good example of that. In reality, millions of wavelengths of light mix together in different combinations and reflect from different parts of the ball. The eyes and the brain, however, simplify that complexity into the property of colour. Colour is a construct of the brain. It’s a caricature, a proxy for reality, and it’s good enough for basic survival.

Is the robot conscious of the ball in the same sense as you? Would it claim to have an inner feeling?

But the brain does more than construct a simplified model. It constructs vast numbers of models, and those models compete with each other for resources. The scene might be cluttered with tennis racquets, a few people, the trees in the distance – too many things for the brain to process in depth all at the same time. It needs to prioritise.

That focussing is called attention. I confess that I don’t like the word attention. It has too many colloquial connotations. What neuroscientists mean by attention is something specific, something mechanistic. A particular internal model in the brain wins the competition of the moment, suppresses its rivals, and dominates the brain’s outputs.

All of this gives a picture of how a normal brain processes the image of a tennis ball. And so far there’s no mystery. With a computer and a camera we could, in principle, build all of this into our robot. We could give our robot an internal model of a ball and an attentional focus on the ball. But is the robot conscious of the ball in the same subjective sense that you might be? Would it claim to have an inner feeling? Some scholars of consciousness would say yes. Visual awareness arises from visual processing.

I would say no. We’ve taken a first step, but we have more work to do.

Let’s ask the robot. As long as we’re doing a build-a-brain thought experiment, we might as well build in a linguistic processor. It takes in questions, accesses the information available in the robot’s internal models, and on that basis answers the questions.

We ask: ‘What’s there?’

It says: ‘A ball.’

We ask: ‘What are the properties of the ball?’

It says: ‘It’s green, it’s round, it’s at that location.’ It can answer that because the robot contains that information.

Now we ask: ‘Are you aware of the ball?’

It says: ‘Cannot compute.’

Why? Because the machine accesses the internal model that we’ve given it so far and finds no relevant information. Plenty of information about the ball. No information about what awareness is. And no information about itself. After all, we asked it: ‘Are you aware of the ball?’ It doesn’t even have information on what this ‘you’ is, so of course it can’t answer the question. It’s like asking your digital camera: ‘Are you aware of the picture?’ It doesn’t compute in that domain.

But we can fix that. Let’s add another component, a second internal model. What we need now is a model of the self.

A self-model, like any other internal model, is information put together in the brain. The information might include the physical shape and structure of the body, information about personhood, autobiographical memories. And one particularly important part of the human self-model is called the body schema.

The body schema is the brain’s internal model of the physical self: how it moves, what belongs to it, what doesn’t, and so on. This is a complex and delicate piece of equipment, and it can be damaged. The British neurologist Oliver Sacks tells the story of a man who wakes up in the hospital after a stroke to find that somebody has played a horrible joke. For some reason there’s a rubbery, cadaverous leg in bed with him. Disgusted, he grabs the leg and throws it out of bed. Unfortunately, it is attached to him and so he goes with it.

Evidently, in Sack’s story, a part of the man’s internal model of his self has become corrupted in such a way that he can no longer process the fact that his leg belongs to him. But there are many ways in which brain damage can disrupt one or another aspect of the self-model. It’s frighteningly easy to throw a spanner in the works.

We say to the machine: ‘Tell us about yourself’

Now that our build-a-brain has a self-model as well as a model of the ball, let’s ask it more questions.

We say: ‘Tell us about yourself.’

It replies: ‘I’m a person. I’m standing at this location, I’m this tall, I’m this wide, I grew up in Buffalo, I’m a nice guy,’ or whatever information is available in its internal self-model.

Now we ask: ‘What’s the relationship between you and the ball?’

Uh oh. The machine accesses its two internal models and finds no answer. Plenty of information about the self. Plenty of separate information about the ball. No information about the relationship between the two or even what the question means.

We ask: ‘Are you aware of the ball?’

It says: ‘Cannot compute.’

We’ve hit another wall. Equipped only with those two internal models, the robot fails the Turing test again: the machine cannot pass for human.

Why have internal models at all? The real use of a brain is to have some control over yourself and the world around you. But you can’t control anything if you don’t have a good, updated dossier on it, knowing what it is, what it’s doing, and what it might do next. Internal models keep track of things that are useful to monitor. So far we’ve given our robot a model of the ball and a model of itself. But we’ve neglected the third obvious component of the scene: the complex relationship between the self and the ball. The robot is focusing its attention on the ball. That’s a resource that needs to be controlled intelligently. Clearly it’s an important part of the ongoing reality that the robot’s brain needs to monitor. Let’s add a model of that relationship and see what it gives us.

Alas, we can no longer dip into standard neuroscience. Whereas we have decades of research on internal models of concrete things such as tennis balls, there’s virtually nothing on internal models of attention. It hadn’t occurred to scientists that such a thing might exist. Still, there’s no particular mystery about what it might look like. To build it into our robot, we once again need to decide what information should be present. Presumably, like the internal model of the ball, it would describe general, abstracted properties of attention, not microscopic physical details.

For example, it might describe attention as a mental possession of something, or as something that empowers you to react. It might describe it as something located inside you. All of these are general properties of attention. But this internal model probably wouldn’t contain details about such things as neurons, or synapses, or electrochemical signals – the physical nuts and bolts. The brain doesn’t need to know about that stuff, any more than it needs a theoretical grasp of quantum electrodynamics in order to call a red ball red. To the visual system, colour is just a thing on the surface of an object. And so, according to the information in this internal model, attention is a thing without any physical mechanism.

With our latest model, we’ve given the machine an incomplete, slightly inaccurate picture of its own process of attention – its relationship to that ball. When we ask: ‘What’s the relationship between you and the ball?’ the machine accesses its internal models and reports the available information. It says: ‘I have mental possession of the ball.’

That sounds promising. We ask: ‘Tell us more about this mental possession. What’s the physical mechanism?’ And then something strange happens.

The models don’t contain detailed specifications of how attention is implemented. Why would they? So the build-a-brain can answer only based on its own incomplete knowledge. When asked, naive people don’t say that colour is an interaction between millions of light wavelengths and their eyes: they say it is a property of an object. After all, that’s how their brain represents colour. Similarly, the build-a-brain will describe its model’s own abstractions as if they somehow floated free of any specific implementation, because that’s (at best) how they will be represented within its self-model.

It says: ‘There is no physical mechanism. It just is. It is non-physical and it’s located inside me. Just as my arms and legs are physical parts of me, there’s also a non-physical part of me. It mentally possesses things and allows me to act with respect to those things. It’s my consciousness.’

We built the robot, so we know why it says that. It says that because it’s a machine accessing internal models, and whatever information is contained in those models it reports to be true. And it’s reporting a physically incoherent property, a non-physical consciousness, because its internal models are blurry, incomplete descriptions of physical reality.

now we have something that begins to sound spooky. We have a machine that insists it’s no mere machine

We know that, but it doesn’t. It possesses no information about how it was built. Its internal models don’t contain the information: ‘By the way, we’re a computing device that accesses internal models, and our models are incomplete and inaccurate.’ It’s not even in a position to report that it has internal models, or that it’s processing information at all.

Just to make sure, we ask it: ‘Are you positive you’re not just a computing machine with internal models, and that’s why you claim to have awareness?’

The machine, accessing its internal models, says: ‘No, I’m a person with a subjective awareness of the ball. My awareness is real and has nothing to do with computation or information.’

The theory explains why the robot refuses to believe the theory. And now we have something that begins to sound spooky. We have a machine that insists it’s no mere machine. It operates by processing information while insisting that it doesn’t. It says it has consciousness and describes it in the same ways that we humans do. And it arrives at that conclusion by introspection – by a layer of cognitive machinery that accesses internal models. The machine is captive to its internal models, so it can’t arrive at any other conclusions.

Admittedly, a tennis ball is a bit limited. Yet the same logic could apply to anything. Awareness of a sound, a recalled memory, self-awareness – the build-a-brain experiment shows how a brain could insist: ‘I am aware of X.’

And this is the central question of consciousness.

Consciousness research has been stuck because it assumes the existence of magic. Nobody uses that word because we all know there’s not supposed to be such a thing. Yet scholars of consciousness – I would say most scientific scholars of consciousness – ask the question: ‘How does the brain generate that seemingly impossible essence, an internal experience?’

By asking the question, scholars set up an even bigger mystery. How does that subtle essence emerging from the brain turn around and exert physical forces, directing this pathway and that synapse, enabling me to type about it, or scholars to argue about it? There is a kind of magical incoherence about the approach.

But we don’t need magic to explain the phenomenon. Brains insist they have consciousness. That insistence is the result of introspection: of cognitive machinery accessing deeper internal information. And an internal model of attention, like the one we added to our build-a-brain, would contain exactly, but exactly, that information.

A popular trend in some circles is to dismiss consciousness as an illusion. It doesn’t exist and therefore can’t possibly serve any purpose. When people first encounter the Attention Schema theory, they sometimes put it in that iconoclastic category. That is a mistake. In this theory, consciousness is far from useless. It’s a crucial part of the machine.

Suppose you have a city map. It’s definitely useful. Without it, you might never reach your goal. Is the map a perfect rendering of the city? No. There is no such thing as a two-dimensional, black-and-white city filled with perfectly straight paths and neat angles. But the city itself is real, the map is real, the information in it is mostly valid if simplified, and so the map is unquestionably of practical use. Knowing all this, you probably won’t suffer an existential crisis over the reality of the city or dismiss the contents or the existence of the map as an illusion. The truth is much simpler: your model of the city is helpful but not perfectly accurate.

Gone are the days of waiting for computers to get so complicated that they spontaneously become conscious

There is a real thing that we call attention – a wildly complex, beautifully adapted method of focusing the brain’s resources on a limited set of signals. Attention is important. Without it, we would be paralysed by the glut of information pouring into us. But there’s no point having it if you can’t control it. A basic principle of control theory is this: to control something, the system needs an internal model of it. To monitor and control its own attention, the brain builds an attention schema. This is like a map of attention. It contains simplified, slightly distorted information about what attention is and what it is doing at any particular moment.

Without an attention schema, the brain could no longer claim it has consciousness. It would have no information about what consciousness is, and wouldn’t know how to answer questions about it. It would lack information about how the self relates to anything in the world. What is the relationship between me and the ball? Cannot compute.

More crippling than that, it would lose control over its own focus. Like trying to navigate a city without a map, it would be left to navigate the complexities of attention without a model of attention. And even beyond that, lacking a construct of consciousness, the brain would be unable to attribute the same property to other people. It would lose all understanding that other people are conscious beings that make conscious decisions.

Consciousness matters. Unlike many modern attempts to explain it away, the Attention Schema theory does exactly the opposite of trivialising or dismissing. It gives it a place of importance.

As long as scholars think of consciousness as a magic essence floating inside the brain, it won’t be very interesting to engineers. But if it’s a crucial set of information, a kind of map that allows the brain to function correctly, then engineers may want to know about it. And that brings us back to artificial intelligence. Gone are the days of waiting for computers to get so complicated that they spontaneously become conscious. And gone are the days of dismissing consciousness as an airy-fairy essence that would bring no obvious practical benefit to a computer anyway. Suddenly it becomes an incredibly useful tool for the machine.

Building a functioning attention schema is within the range of current technology. It would require a group effort but it is possible. We could build an artificial brain that knows what consciousness is, believes that it has it, attributes it to others, and can engage in complex social interaction with people. This has never been done because nobody knew what path to follow. Now maybe we have a glimpse of the way forward.