Listen to this essay

24 minute listen

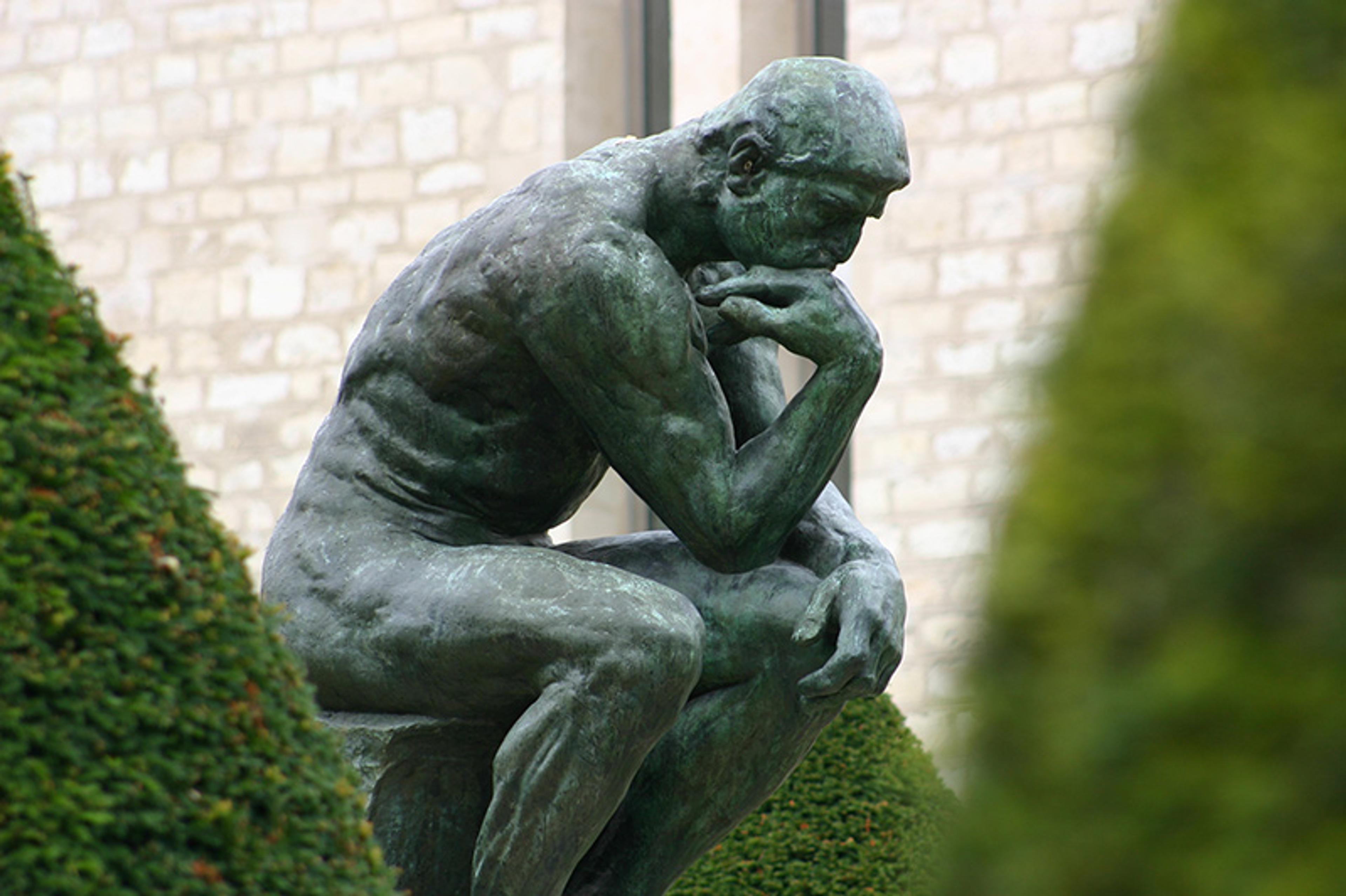

One can easily imagine Auguste Rodin’s The Thinker (1904) tortured by deep philosophical questions such as ‘Who am I? What is the meaning of all this, what is life? Why am I here, given that I haven’t signed a consent form to be alive here and now, so what’s this all about, really?’

I too was tortured by these deep questions as a young student in philosophy, and used to ponder them standing in front of a cast of Rodin’s statue in the grounds of the Hôtel Biron in Paris. I guess I was looking for something, the meaning of all this. Since then, and after drinking so much coffee that I could flood a city with it, I still haven’t got an answer. And yet, one day, something happened: a breakthrough, or perhaps an epiphany.

The Thinker in the grounds of the Musée Rodin, Paris. Courtesy VC/Flickr

A couple of years ago, I went back to The Thinker as I had so many times when younger: he was still there, still thinking, holding his head as if all those deep, heavy thoughts had transformed his skull to stone.

While searching for the right angle to take a selfie, a miracle happened: I got hungry. Partly because of the heat, partly because I’d had just one black coffee in the morning, the head of Rodin’s Thinker started tilting and melting, and the massive weight of his body became visible to my mind. It was as if the statue was slowly liquefying and transforming into a vegetal living thing, something like a salad, or perhaps a cucumber? Something fresh anyway, something that I could have eaten on the spot. And then some questions popped into my head: did the Thinker like cucumber salad? Where did he grow up? Did he prefer summer or winter? White wine or red? Where was he from?

And in that moment I realised I had got it all wrong. I was so obsessed with his thinking brain that I had ignored his toes – not to mention the rest of him.

Brains are highly fashionable. A very common belief is that the human mind and cognition lie in the head, within the confines of a spongy greyish organ called ‘the brain’ encased within skull and skin. While I was looking at that Thinker’s head, with my stomach protesting, I realised I had completely dismissed his body. I was obsessed with understanding his mind, and my mind via his brain, but I completely ignored the rest of him. Like the great majority of scientists and philosophers throughout history, I too was putting cognition into the head and forgetting about the body, treating it as something that got in the way of pure cerebral thought.

Being a philosopher hadn’t been my only dream.

Why are we so reluctant to consider the brain as just another part of the body?

I’d decided to study philosophy after becoming a frustrated musician. My parents, God bless them, considered that singing opera and playing piano were cool ways to impress the visitors, but wouldn’t lead to a career. Now they regret their decision not to allow me to take a musical path. When visitors politely ask what their daughter is doing for a living and they reply: ‘She’s a philosopher,’ the visitors look puzzled as if needing an extra explanation: ‘Yes, but what exactly is she doing?’ My parents can’t say ‘she’s thinking’ because that would make them look silly, and they are extremely proud and reasonable folks. Now, if I were a musician, well, that would have been way simpler. Everyone gets what musicians do.

There is no doubt a modern fascination with the thinking brain as the fundamental basis of human cognition. But why? Is this the only entrance point that allows us to understand who we are and what human cognition is? Here I propose another angle. While neurons are indeed fascinating, their complex activity is only part of the story of human cognition.

After all, brains are part of the body, and bodies are made of cells and many other constituents, some of which are not literally ours, like our unique DNA is. There are many ‘Brain and Body’ research institutes around the world, but no ‘Liver and Body’ institutes. Why is that? It’s because we think the liver is (part) of the body. But why are we so reluctant to consider the brain as just another part of the body? There’s no evidence that the brain is made of a different kind of ‘physical stuff’ from the rest of the body.

I propose a shift in focus from neural to cellular processing to highlight the fundamental role of cells in constituting biological self-organising systems such as the human body.

The journey of understanding who we are, scientifically and philosophically, starts traditionally with a thinking guy – yes, it’s usually a guy, a solitary male genius – sorting out the mystery of the Universe from within his ivory tower. Yet, the journey of who we are as living beings starts way before, when a couple of cells start negotiating energetic resources with some other bunch of cells in the depths of a womb.

As a philosopher/frustrated musician/cognitive neuroscientist, I now give academic talks all over the world, and one of my favourite things to do is to say the following line while carefully scanning the audience for their reactions: ‘You have all spent time growing inside another person’s body.’ Most of the time, people’s eyes widen as if some big mystery has just been revealed to them. Some nod their heads, others seem perplexed or in denial. But surely these smart academics know that babies don’t just drop from the sky or pop out from cabbages? As adults, we all know that we have been babies ourselves, and that we have all developed inside another person’s body. Why is this biological and scientific fact so difficult to recognise for our intelligentsia? Why are we so obsessed with minds, with pure self-conscious minds, while forgetting about bodies, and specifically about the other body that carried and fed our own one? Just think about it: long before being these lovely adults with hopes and dreams and failures, drinking coffee, paying taxes, and reading fancy books and articles online, each of us spent some time as a single cell.

Even more mind-blowing: all human beings gradually develop from cells to a human body within another human body. Pregnancy is a universal human fact that concerns everyone, not just a few of us. All cells of the human organism originate from a single cell, the zygote, are closely interconnected, mutually influence one another, and operate in synchrony to achieve common goals – maintenance of homeostasis and constant adaptation to changes of the surrounding environment. This means that we arrive into this world not on a solitary rock dropped by some mastermind, but as living biological creatures deeply dependent upon and connected with another living body. And then we need others to take care of us for quite some time before we can find a rock to sit on and think about deep things like the meaning of life or quantum physics.

For that Thinker to contemplate the meaning of life, he has to self-regulate his humble internal bodily states

To understand minds, we need to grasp first how we become minds. We need to start with the cells that compose our humble toes before zooming into the mystery of the brain. Why? Because our cells solve the biggest and most urgent problem of this great and mysterious adventure called life without a brain, and before we had a brain: how to stay alive.

Humans are living creatures. Living creatures are self-organising biological systems whose bodies constantly perform the humble yet essential, basic task of keeping track of self-related information-processing to secure survival. In short, this means that your body works for you even when you are asleep or under anaesthesia: your heart keeps beating for you, not for someone else. This also means that all bodily processes have the self at their very core, simply because they obey the universal drive governing all living systems which is: don’t die! Self-preservation is fundamental. But because our body is a living system governed by the basic law of self-preservation, this means that all our experiences are necessarily embodied self-experiences. In perceiving and experiencing the world, we ‘smuggle in’ our own fundamental self-survival goals. This is something we share with cats and worms and viruses. Whether this is also something we share with artificial systems is another story.

Bodily experiences are thus necessarily connected to biological self-regulation (or homeostasis) and self-preservation. For example, a penguin can survive in very cold temperatures, while humans can’t. Every organism has a set of optimal states it has to maintain in order to stay alive. If you are too cold, or too hot, or you need to go to the loo, or you are hungry and dream of salads, then you can’t think properly and solve complex abstract problems. For that Thinker to be able to contemplate the meaning of life on a rock, first he has to successfully self-regulate his humble internal bodily states. In short, the body is life – it is the sine qua non of human existence. If one is alive, one is experiencing through one’s body, even when asleep, even under anaesthesia. And this very simple idea is crucial for redefining how we understand cognition.

How?

Let’s forget for a moment the Thinker, static and isolated on his pedestal, and go back to the growing or developing thinker. How did she get there in the first place? What is this thinker made of? Is she hungry or upset? All these questions may seem silly or irrelevant for the noble question ‘What is cognition?’ but here I suggest that, actually, it’s quite the opposite.

To understand how the neurons work and how we get from neurons to minds, we first need to get back to square one, to understand how we get from cells to selves.

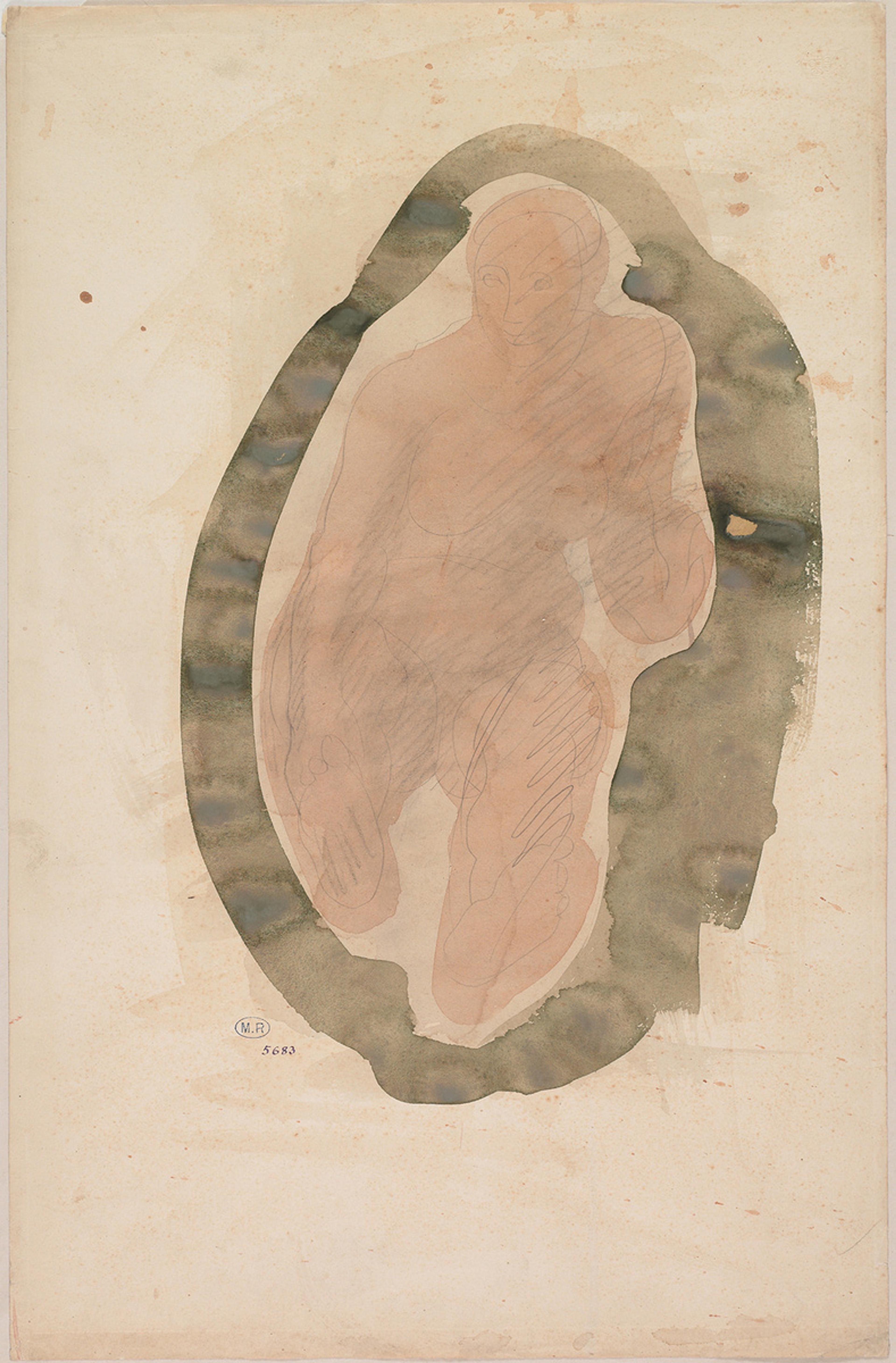

Nude Woman Seated by Auguste Rodin. Photo by Jean de Calan, © and courtesy Musée Rodin, Paris

A growing body of evidence from neurobiology and biochemistry suggests that cognitive categories such as ‘sensing’, ‘memory’ and ‘learning’ can be applied non-metaphorically to the behaviour of simple organisms such as bacteria. Previous work on ‘basal cognition’ questioned the prevailing idea that only brains (ie, collectives of neuronal cells) have the ability to ‘cognise’ or ‘learn’. Rather, non-neural cells and simple organisms may also be perceived as active, primitive ‘cognisers’.

Many thousands of cells must cooperate toward the production of one ‘embryo’ – achieving specific goals in their navigation of anatomical morphospace. But if the blastocyst is cut into pieces, each fragment self-organises its own embryo, resulting in monozygotic twins, triplets and so forth (which may or may not be conjoined). Thus, each cell is some other cell’s ‘external’ neighbour, and the collective must dynamically decide where the embryo ends and the outside world begins.

How do you keep track of you when you don’t have a brain yet?

In addition, a dynamic and complex self-organising system such as the human body needs to be able to play a double poker game, so to speak, to survive and potentially reproduce. First, it must successfully maintain sensory states within certain physiologically viable bounds. Second, it must flexibly change these states to adapt to a volatile world.

Now, suppose you are a cell within a self-organising biological system called the human body and you are obsessed with survival, like all sensible living creatures are. You don’t have a brain yet, no neurons at your disposal, but you still need to survive somehow. What do you do? How do you keep track of you when you don’t have a brain yet? It’s a major puzzle that Nature had to solve via billions of years of trials and errors. And she did! How?

To answer this, we need to answer the following question: which is the basic system at the organismic level that tells your cells which one is your cell, and which one is not? The world is full of signals, and disturbing noise. You have to have some sort of filter that allows you to focus on what is vital for you and to dismiss or fight back against what is not good for you. That’s the job of the immune system. For adaptive biological self-organising systems such as the human body, immune cells develop before neurons, in order to take care and keep track of one’s self.

The new theory I propose here considers all bodily cells and their complex interconnections as being fundamental for cognition, not just neurons. Among our cells, the immune system plays a very special role, working in tandem with the neural system to help us build the ‘self’. The brain is usually considered the conductor of the orchestra playing the concertos of your mind. I disagree. Nature invented a maestro way more discrete, less showy and dazzling perhaps than the brain and its sparkling connections, but older and very efficient!

The metabolic self-regulation and the immune system are fundamental components of organismic self-organisation in humans. It comprises a cellular network capable of distinguishing between self, non-self, missing self, and aberrant self, including misplaced cells and aberrant intracellular and extracellular molecules. In addition, the immune system also regulates the nervous system, behaviour, metabolism and thermogenesis, and takes part in the fight-or-flight response.

The neuroimmune tandem acts as key ‘fact-checker’ for all incoming information relevant for self-survival. From the body’s perspective, there is no such thing as perceptual time off or ‘blackout’ (except when one is dead). The body needs to keep track of one’s ‘self’ information all the time.

Being fundamentally a bodily system, the brain needs to carefully orchestrate and align its neural processing with a complex network of other types of cellular processing, particularly the immune system, to ensure the organism’s survival and to allow it to continue to have viable interactions with the world. Importantly, this idea was already present in the pioneering thinking of Francisco Varela and colleagues who spent quite some time working on the immune system in relation to cognitive systems.

Well before neurons get off the ground, your immune system needs to be clever enough to tell which cell is ‘self’ and which one is not. If, for some reason, your immune cells get tricked and let a virus in, say, then that may be the end of our Thinker, and no contemplation of the meaning of life on a rock will be possible afterwards. Life happens way before, at the bodily, cellular level, without our explicit awareness. And life happens to us without our permission, so to speak. None of us chose to be alive. It simply happens to us. It happened to my cat, Simon too!

One can experience without thinking, but one cannot think without experiencing

When we begin examining and introspecting the human mind and its mysteries systematically, as a scientific and philosophical endeavour, inevitably we are adults and hence we question the world from our adult perspective. In doing so, however, we may blindly use an adult-biased lens, which prevents us from capturing fundamental aspects of our minds. This observation seems trivial at first sight, yet it is not.

Humans do not pop out like Athena from Zeus’ head, or like the Thinker from Rodin’s hands. Rather, we are gestated, born, developing, decaying, and eventually dying. In real life, only at very rare occasions can one afford to stop and think like Rodin’s character, solitary and isolated on a rock. In real life, one needs to move, to interact, to change, to fall, to get up and fall again. Most of the time, we need to think on the fly while acting and interacting with the world and others. Also, we are rarely alone, and we are never just abstract minds, we are deeply embodied creatures, driven by hunger and longing to connect.

Now, is this piece about how eating salads and connecting with your mother is more important than thinking? In a way, yes. You can exist without thinking, but you can’t exist (for very long) without eating or connecting with others.

To put it bluntly: one can experience without thinking, but one cannot think without experiencing. Experiences come to the surface of being through the body, and not through the minds, or some sort of homunculus sitting in our heads, trying to ‘make sense’ of a world he doesn’t see, because the world is hidden in the black box of the scalp. We don’t perceive the world through some sort of inner solitary lens situated in our heads. We perceive the world through every single cell of our body.

And because human bodies first develop within another human body, at the beginning of our life, we perceive the world literally through another body.

This is what thinking is for: dealing with the messy jungle of life rather than the clean space of chess-playing

In pregnancy, (at least) two immune systems need to negotiate the exchange of resources and information in order to maintain viable self-regulation of nested systems. The relationship, and the interactions between the two self-organising systems during pregnancy may play a pivotal role in understanding the nature of biological self-organisation per se in humans.

While it was traditionally assumed that the placenta and the fetus are non-active immunological organs – largely depending on the maternal immune system – recent work suggests a more complex picture. The placenta and the fetus represent an ‘additional immunological organ which affects the global response of the mother to microbial infections,’ as the physiology researchers Gil Mor and Ingrid Cardenas put it. The type of response initiated in the placenta may determine the immunological response of the mother, impacting the pregnancy outcome. The placenta represents an active immunological organ, highly responsive to foreign pathogens. For example, it has been shown that the placenta functions as a regulator of, rather than a barrier to, the trafficking between the fetus and the mother. Both the fetus and the placenta present an active immune system that has a direct effect on the way the mother responds to the environment. Importantly for our discussion here, the placental-immune system creates a pregnancy-friendly protective environment while still being fully operational and able to defend the mother and fetus against infections.

Life is always a collective decision and a collective endeavour. If this is so, then why are we focusing on solitary brains and high-level cognitive abilities such as chess-playing to understand cognition? The radical claim here is that a creature with neurons only cannot develop, act and survive in the wild. And, ultimately, this is what thinking is for: successfully dealing with the messy and unpredictable jungle of life rather than with the clean and predictable space of chess-playing.

Perhaps all those modern obsessions about thinking and neural models of cognition were built to raise high the ceiling of our pure minds protecting us from the impure, messy and constantly dying and birthing cells of our bodies.

But what if we are experiencing and cognising the world with every single cell in our entire body, not just the maestro brain? All our humble bodily cells participate in the making of our experiences and cognitive processes, and not just the ‘noble’ neurons in the brain.

Does this really mean that we need our whole body to think? Surely I can cut off my toe, say, and still think? So what exactly is meant by saying that cognition is not in the brain and that I need the whole body? However, the really important question is: was your body ‘dumb’ before you had a brain? If so, how did you manage to survive without neurons? Who did the smart heavy lifting of information-processing for survival, to allow brains to grow properly in the first place?

Interestingly, that famous Rodin sculpture was supposed to represent not a philosopher, but a poet – Dante, the author of The Divine Comedy. The artist represented the poet sitting at the door of the Inferno and other worlds, contemplating the space in between, the border, the passage between life and death. Perhaps what Rodin was trying to show us was that the meaning of all this lies not hidden inside one’s head, but in what lies in between us, the world, and others. And here I say that this fascinating ‘in between’, for which we don’t have a word in our Western societies yet, starts already in the womb, with the placenta, the mysterious messy bridge that brings life to life through another’s living body.