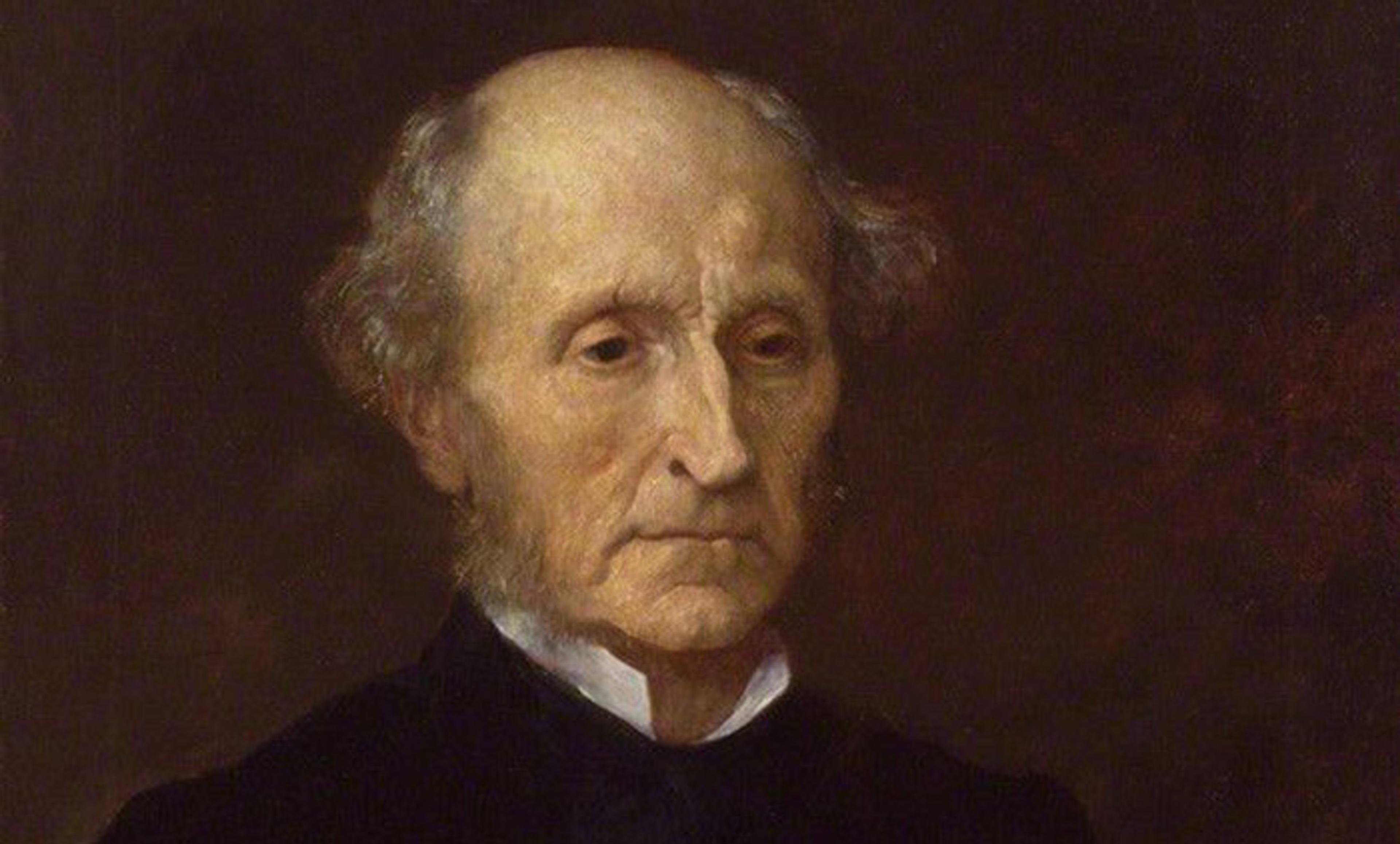

William Blake, The Good and Evil Angels 1795–c.1805. CC-BY-NC-ND © Tate

The problem of evil is a classic dilemma in the philosophy of religion. The relative ease with which the problem can be stated belies the depth of the challenge that it presents to traditional monotheism. Roughly, it can be summarised as follows:

If God is omnipotent, then He has the power to create a world without evil.

If God is omniscient, then no moment of evil goes divinely unnoticed.

If God is omnibenevolent, then He has the desire to rid the world of evil.

Therefore, the world should be perfect, or at least free of undeserved suffering. Yet, a cursory glance reveals a world that clearly is not inherently just or free from undeserved suffering.

Hence, the problem of evil: how can a perfect deity allow such injustice and rampant evil in the world that He created?

Many solutions to the problem of evil – called ‘theodicies’ – have been proposed. There is the argument of free will, attributing evil not to God but to humanity’s misuse of its own freedom. Others have argued that certain kinds of moral goodness – compassion, for instance – are not possible in a world without evil, and the value of these types of goodness outweighs the evils on which their existence depends. There is also what I call ‘the big-picture defence’, claiming that evil only appears as such from our limited perspectives. Were we able to see things from the perspective of God, we would see that, in the grand scheme of things, every apparent evil plays a necessary role in making the world more perfect.

The philosopher Gottfried Leibniz’s simple solution was to argue in 1710 that this world is necessarily the best of all possible worlds. Leibniz depicts God assessing in His infinite mind all the various possible worlds that He could create. Because He is a loving God, the one He chooses to create is surely the ‘best of all possible worlds’. Leibniz’s argument suggests that it is ultimately meaningless to complain about this evil or that injustice; because this is the best of all possible worlds. We should take comfort in the fact that everything is, in the final analysis, as good as it can possibly be.

Voltaire derided Leibniz’s solution, writing a book to satirise it. In Candide (1759), the eponymous hero and his companions stumble through the world, constantly beset by bad luck and predations. They witness even greater tragedies in the world around them. Their troubles arise from the uncaring forces of the natural world, but also from the naiveté of Candide, who is constantly assured by his mentor, Professor Pangloss, that this is indeed the best of all possible worlds. In juxtaposing vivid depictions of myriad cruelties and Professor Pangloss’s blind insistence on the ultimate goodness of the universe, Voltaire demonstrates that there is a poignant reality to the experience of suffering that cannot be rationalised away. The claim that justice naturally inheres in the order of things does not bear scrutiny.

There is also a profound moral danger to certain types of theodicy.

The essential difficulty of the problem of evil is how to reconcile its apparent existence with a loving, all-powerful deity. One popular method has been to reassert the inherent justice of the world, implying, if not explicitly claiming, the righteousness of the suffering that we witness throughout it. The result is, essentially, a theological form of victim-blaming.

For example, the American evangelical preacher Pat Robertson explained the 2010 earthquake in Haiti – which killed between 220,000-316,000 people, and injured another 300,000 – as the fault of the Haitian people. The people of Haiti had apparently sworn a pact with Satan in exchange for delivering them from French rule, and the earthquake was divine retribution for that bargain (delivered approximately two centuries later). Robertson similarly suggested that both Hurricane Katrina and terrorism were divine punishment for the fact that abortion is still legal in the United States. Robertson, of course, is not alone. An Iranian mullah has blamed earthquakes on women dressing immodestly; a New York rabbi blamed the advancement of gay rights in the US for another earthquake in 2011; many Burmese Buddhists blamed a 2008 cyclone that killed approximately 130,000 people on bad karma.

The desire that motivates these interpretations is understandable. Natural disasters and terrorist attacks are either random events in a chaotic world, or they are explicable events within a discernible pattern. In the former case, we inhabit an essentially amoral universe: bad things happen to good people, children die premature deaths, and tragedy strikes without remorse, all without rhyme or reason. In the latter case, we inhabit a much more hospitable universe where there is some sort of inherent order: a place where morality is inscribed into the very fabric of things, assuring us that, if only we play by the rules, evil will be punished, goodness will be rewarded, and justice will reign supreme.

It is easy to understand the attraction of that vision. But it has a substantial dark side. Like any theodicy, it cannot simply unmake suffering, and so it instead tries to justify it. The claim that the universe is inherently just then implies that those who suffer deserve it. The existence of a just God and a moral universe is gained at the cost of condemning victims of misfortune as blameworthy. And so, hundreds of thousands of Haitians died because their ancestors made a pact with the devil. Women and homosexuals agitating for equal rights are blamed for deadly natural disasters.

Such a worldview conveniently scapegoats someone, usually whatever population someone wishes to demonise: women, homosexuals, the poor, etc. It also normalises social ills that could otherwise be addressed and meliorated. In a dark irony, holding that the universe is ultimately a just place ends up condoning the suffering and injustice that happens within it, often on the backs of those most in need.

Visions of a just universe need not function this way. Theodicy authorises only the suffering of the less fortunate when it indulges in willful blindness and insists on justice as a foregone conclusion, denying reality in favour of comforting ignorance. Alternatively, when justice is construed as hope – as a vision of what the world could possibly be – it functions as a lodestar. This acknowledges the disturbing realities with which we are surrounded, and refuses to be disillusioned by them. By regarding justice as an ideal rather than a present reality, one’s vision of the inequalities and brutalities of the present moment remains unobstructed, allowing them to be faced. The just universe in which we should believe is the one that can be created only through dedicated effort and real action on our part. But that can happen only if we refuse to take shelter in soothing fantasies.