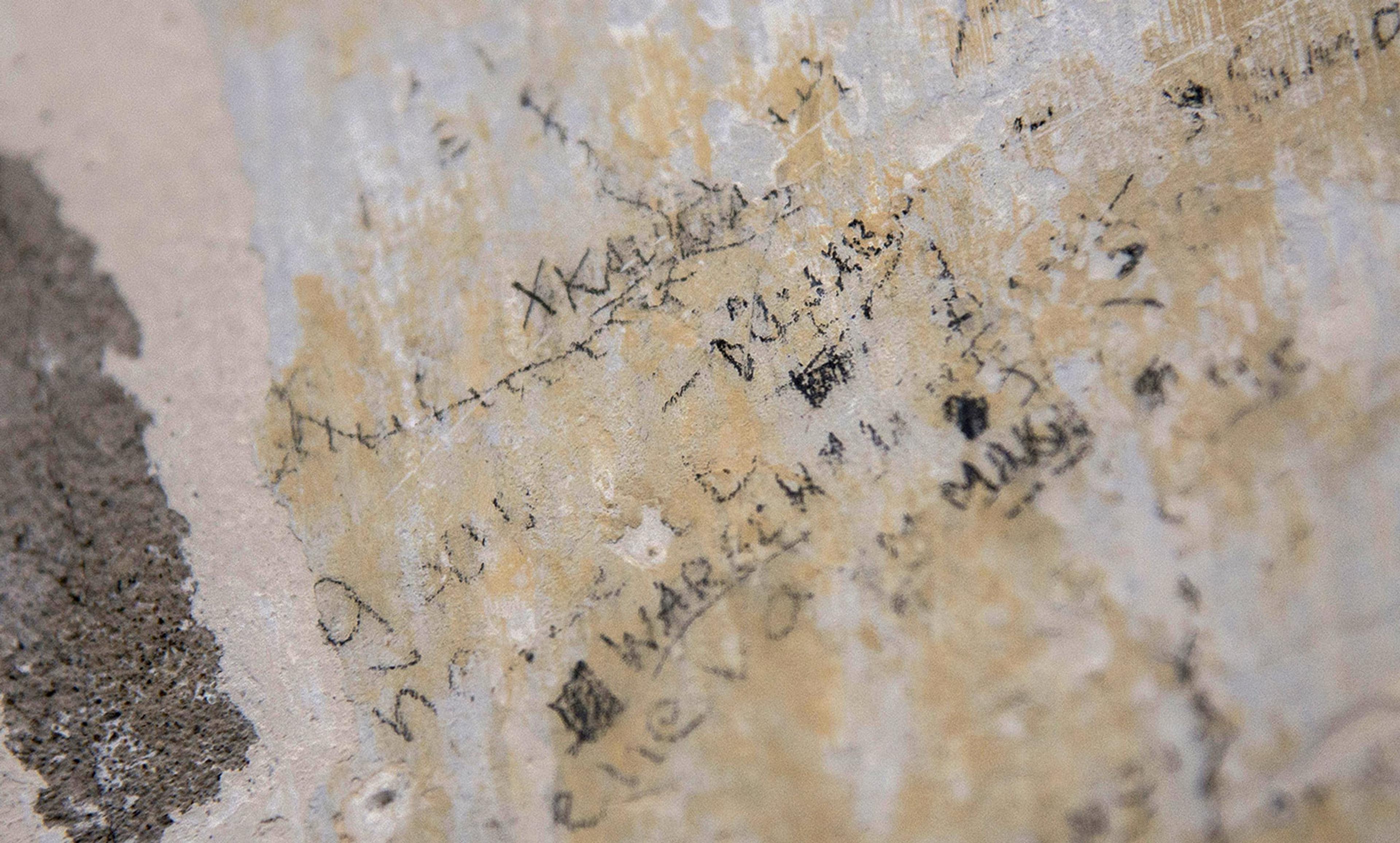

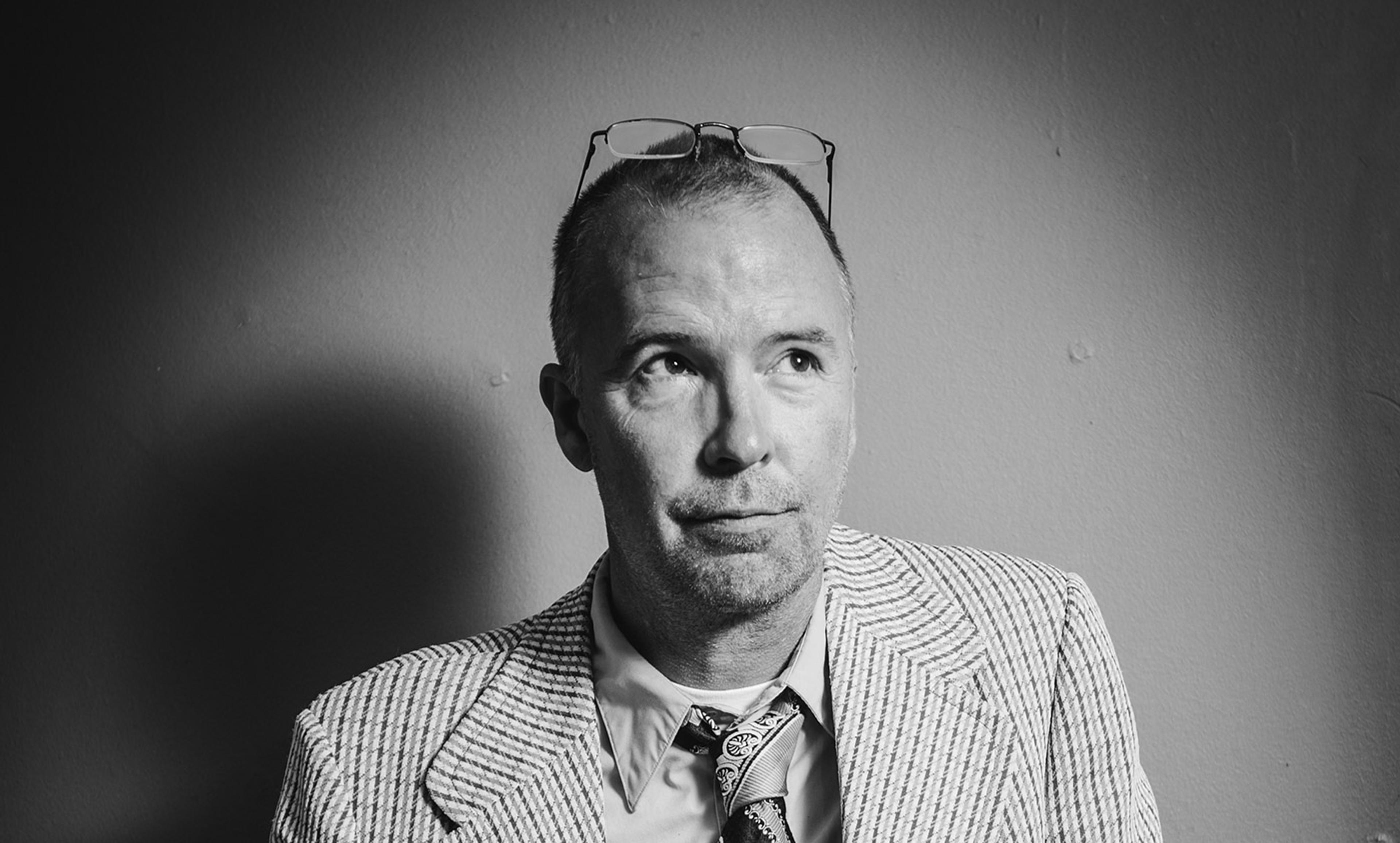

Panel from Abina and the Important Men (2012) by Trevor Getz and Liz Clarke (artist)

I am a historian and, a few years ago, I collaborated with the artist Liz Clarke to produce a history in comic-book form. Together, we created Abina and the Important Men (2012), a graphic history of a 19th-century court case in colonial West Africa. Dozens of graphic histories have been produced in English since then. They showcase both the particular interpretive and communicative advantages of the genre, and the work that remains to grasp those opportunities.

Recently, a skeptical colleague gleefully shared an American comedian’s scathing witticism that only a country that thinks comic books are important could have elected Donald Trump. The opinion that comics dumb down our discourse is one I’ve heard before. It’s not all that surprising, really, given the resistance that faced documentary films and digital data visualisation when they were first presented as ways to interpret the past. But the value of historical comics has already been affirmed in other parts of the world.

Shigeru Mizuki’s series Showa (1988-89) on Japan’s 20th-century history and his manga memoir Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths (1973), which details his experience in the Japanese army, are practically canonical in that country. Jacques Tardi is seen as something of a laureate in France for his visceral account of civilisation turned to savagery during the First World War in It Was a War of the Trenches (1993). And Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991), a reflection on the intergenerational trauma of the Holocaust, had a lasting and broad impact on American culture. Each of these books directly helped people learn about, recognise and grapple with the trauma and history of devastating conflict.

It was teaching that led me to Abina and the Important Men. I was trying to help my students to understand the ways that history amplifies some voices and experiences, and silences others, and the ways in which historians, working in the margins of history, can find these stories and retell them. Looking for a suitable pathway for the students to experience this for themselves, I turned to a court case I had found in the National Archives of Ghana, in which a young African woman took her master to court for illegally enslaving her under British colonial law. As we read Abina Mansah’s testimony together, it became clear just how incredible and important her voice could be.

from Abina and the Important Men (2012)

Captured by an Asante general in one of many wars in the region for control of the profitable palm-oil trade, she was sold as a slave multiple times before she ended up in the British Gold Coast Colony and Protectorate in 1876, two years after enslavement had been criminalised. After only 10 days, she ran away from the man who had purchased her, and managed to convince a Euro-African translator to help her to prosecute him. Her master, Kwamina Adu, was a wealthy man. The British magistrate was reluctant to prosecute him, and he managed to hire a well-trained lawyer. Yet neither Adu, nor his lawyer, nor the magistrate could stop Abina from speaking her truth in court. The resulting testimony is both moving and a significant source for understanding the experiences and perspectives of enslaved women in West Africa, and perhaps beyond.

Abina’s testimony gave me the most successful teaching moments I had ever had, and I knew that I had to share it further. I did not want to lose the power of what we had achieved in that classroom. I wanted to find a way to produce and publish a democratic work that would reach an audience beyond the few academics who would read a peer-reviewed journal article. I needed to build my readers’ sense of identification with Abina, and also to force them to do some intellectual work themselves to hear the messages she communicated in her testimony. I also wanted readers to understand that my analysis was just an interpretation of a very real experience, an attempt to get at a deeper truth creatively, but – because of the very nature of the sources – it was not an authoritative history.

I settled on a graphic history because I believed that the art-and-text combination of the comic medium could draw out readers’ empathy, force them to participate in the story, and convey lessons and meanings that are difficult to express in text alone. Like documentaries, or monuments, or museum didactics, graphic histories represent an interpretation of the past for the public. They cannot represent every story or historical enquiry, of course. Each type of medium has its own set of attributes that befit certain interpretive projects. Comics, for example, work best with character-driven narratives that engage the empathy of the reader. Humans recognise and relate to faces more viscerally and easily than to names on a page.

Bringing art and words together produces unique opportunities to render a milieu for readers. It opens objects, places and people to investigation. However, it also introduces new challenges of representation, demanding attention to details – clothing, environment – which might be peripheral to the historian’s goals or difficult to reproduce. Comics also ask readers to work. Their negative space – the gutters between panels – require that readers make connections to understand the broader story. This attribute builds reader-engagement, but also reduces authorial control over the reader’s interpretation. Indeed, the author of a graphic history has to share power over the story with the artist, the reader and the historical subjects. It makes for a crowded workspace.

When these attributes are taken into account, graphic histories can become excellent vehicles for specific kinds of stories of the past. They are particularly useful for accounts that focus on individual stories that exemplify wider social issues. They are also especially suited to histories that deal with trauma or transformation, which can be represented graphically. Finally, they are excellent vehicles for histories that raise tough questions of interpretation, especially when the art and text are juxtaposed in ways that highlight contrasting theories or understandings of the past.

Two major problems face creators of graphic histories. The first is how to make the visual representation equal to the history. The images and the words together must be greater than the sum of their parts. Verisimilitude is also essential. The narrative and image-centred medium induces the creator to speculate, to fill in, and to introduce both fictional text and visuals of uncertain veracity. A comic can be beautiful but of dubious history, or a solid history but aesthetically lacking. The best historical comics find ways to address these challenges and utilise the medium to its best advantage.

Ari Kelman and Jonathan Fetter-Vorm’s Battle Lines: A Graphic History of the Civil War (2015) is a good example. A study of the transformative quality of violence, the book unfolds from a series of historical artifacts – objects, photographs and documents – interposed with comic-style representations of their origins or the experiences they represent. Much of the dialogue that Kelman and Fetter-Vorm created is between fictional characters, for they didn’t want to invent conversations for real historical actors. Kelman explains that, in a book about the impact of violence, they wanted to avoid doing violence to the past.

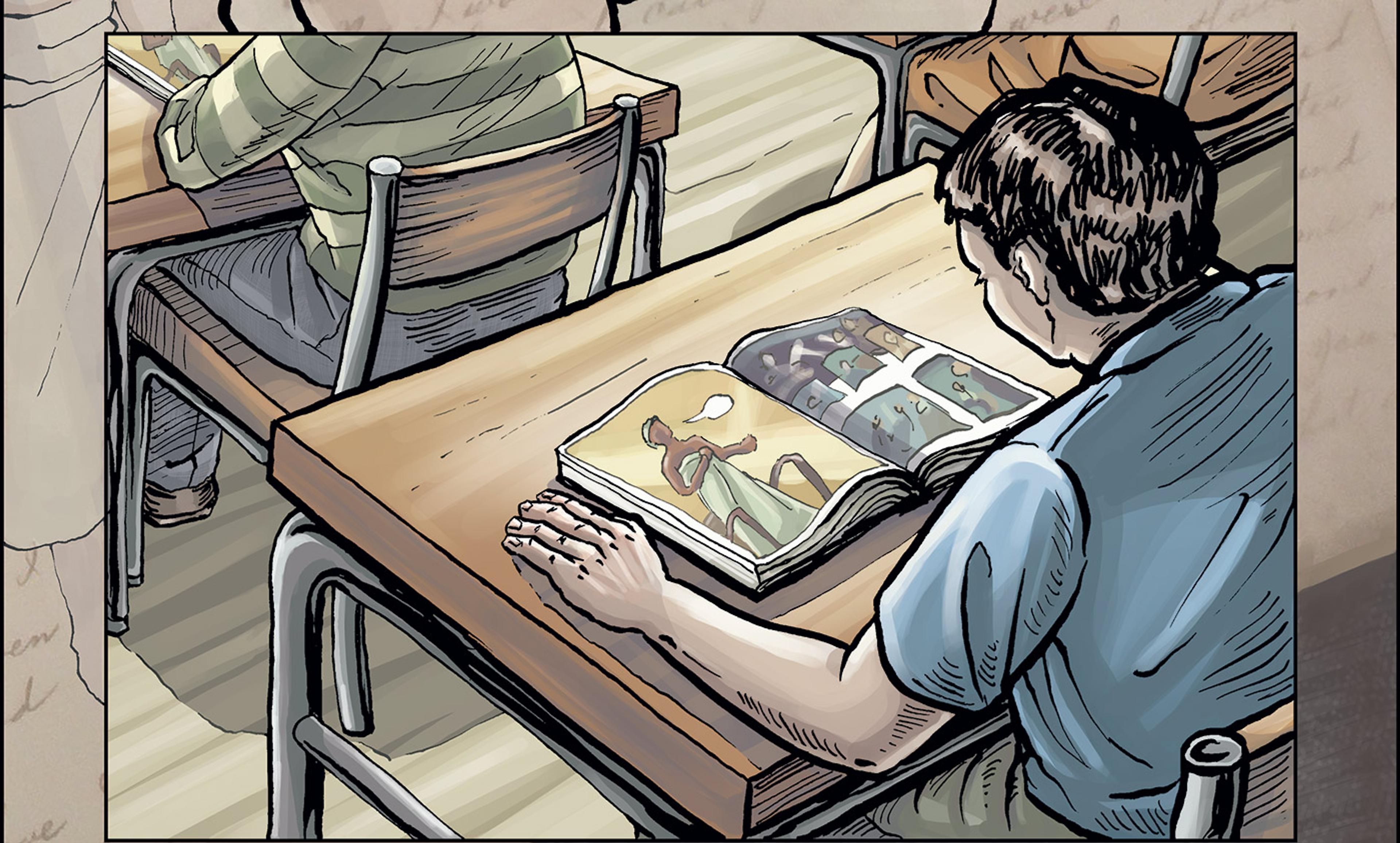

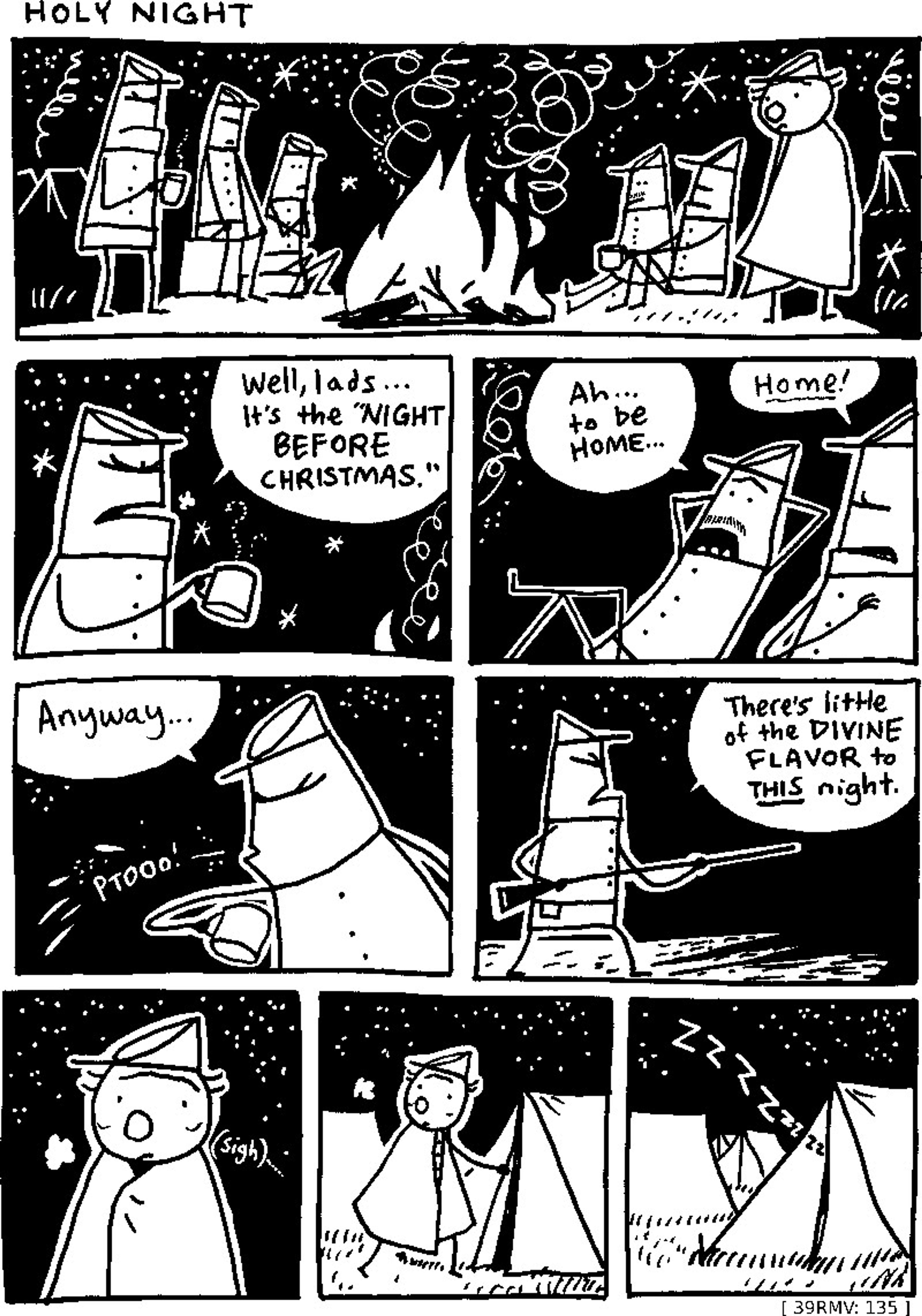

Marek Bennett’s The Civil War Diary of Freeman Colby (2016) faced a similar problem. The diary of this New Hampshire teacher gave Bennett rich material for a graphic history, but we have no actual portrait of Freeman Colby. So Bennett’s work uses stick figures with generic faces to portray his story.

From Marek Bennett’s The Civil War Diary of Freeman Colby (2016)

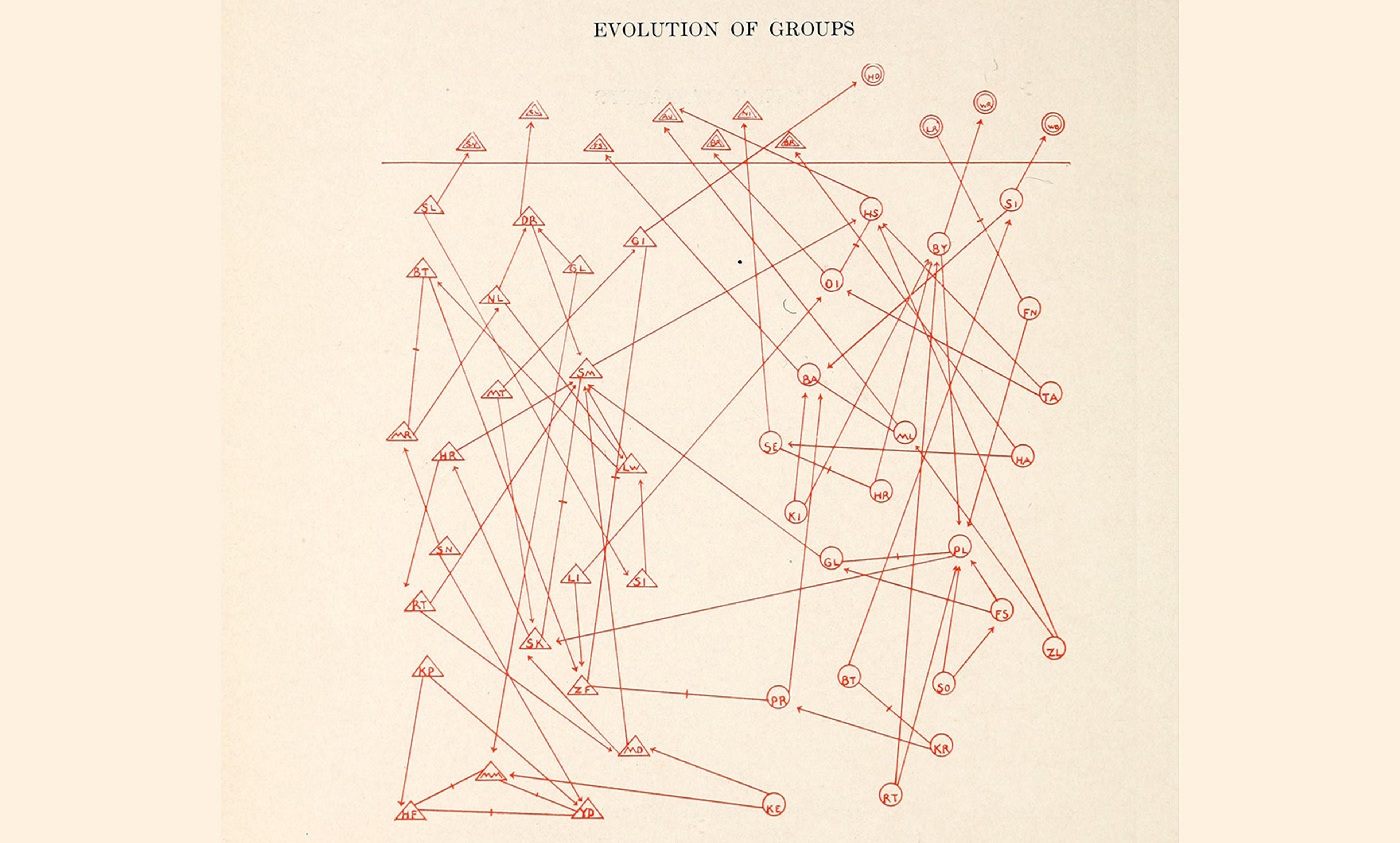

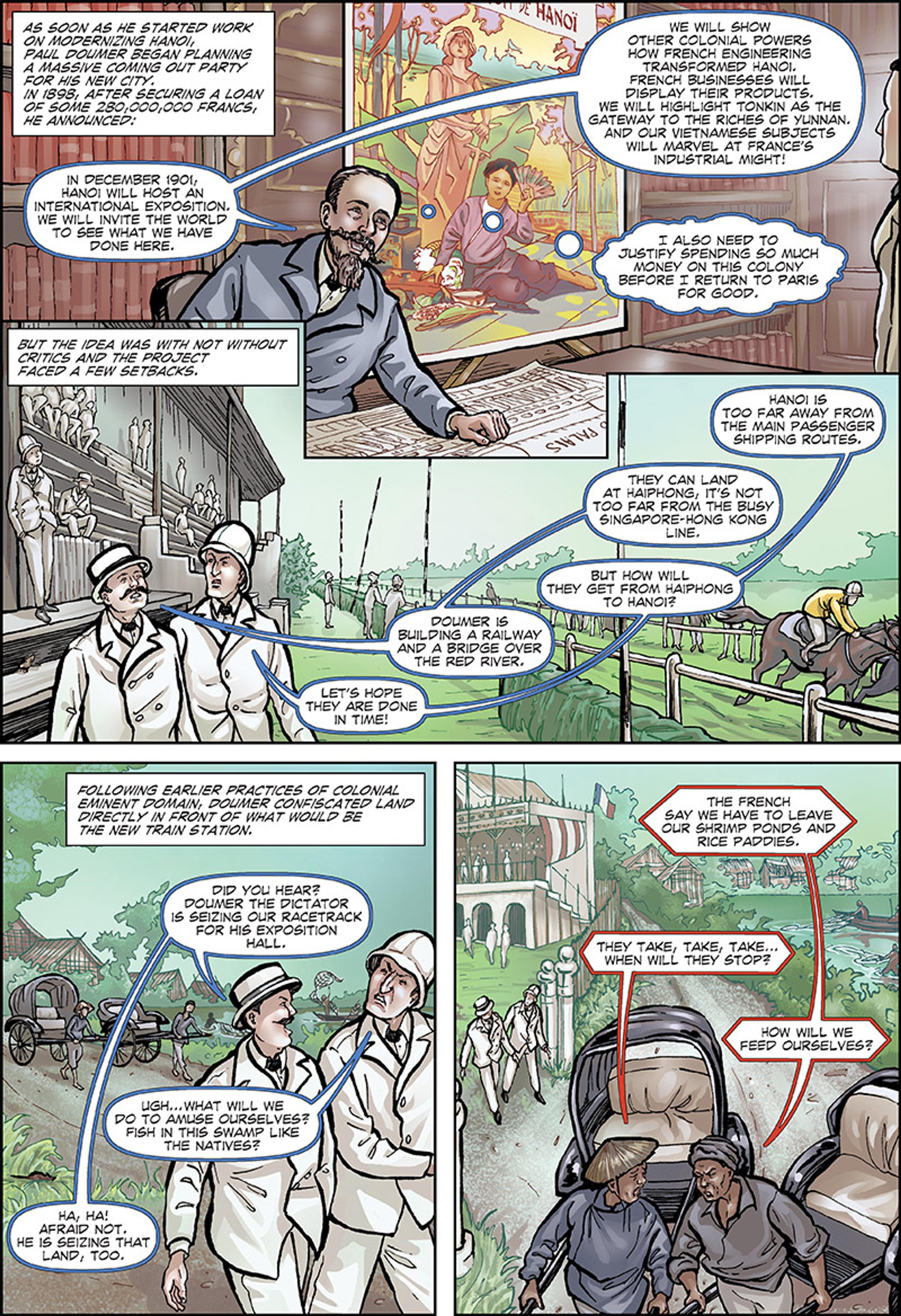

Michael G Vann and Liz Clarke’s The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (2018) is a graphic history that exemplifies the possibilities of using art and text together to ask historical questions. The book engages the segregation of colonial Hanoi and its connection to the wider world, and the design of each page reinforces these themes. Gutters cut through the middle of some pages, dividing Vietnamese and French characters whose speech balloons are drawn in different colours. On other pages, chains or ropes present visual metaphors connecting individuals and street-level views of the city to regional and global maps.

From Michael G Vann and Liz Clarke’s The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam (2018)

Comics can make great history books. They can convey the meaning of the past to the present as effectively as a good textbook or the most detailed monograph. Of course, compared with textbooks, graphic histories will always be a more democratic and multiform genre. The comic book can bring both knowledge and joy to many. Creators of graphic histories can facilitate this experience by taking seriously both the medium and the discipline, and by studying and applying the opportunities, languages and limitations of comics and history together. Readers can help by demanding graphic histories that engage their senses and their intellects, as both scholarship and art.