Philippe Put/Flickr

Surely every child on Earth should be loved. That seems obvious. But is that a human right? Many international declarations adopt this view. The 1989 Declaration on the Rights of the Child in Israel, for instance, states that every child has ‘the right to a family life – to nourishment, suitable housing, protection, love and understanding’; the 1979 Declaration of the Rights of Mozambican Children claims that they have ‘the right to grow up in a climate of peace and security, surrounded by love and understanding’; and the 1951 Children’s Charter of Japan asserts that they shall be ‘entitled to be brought up in their own homes with proper love’.

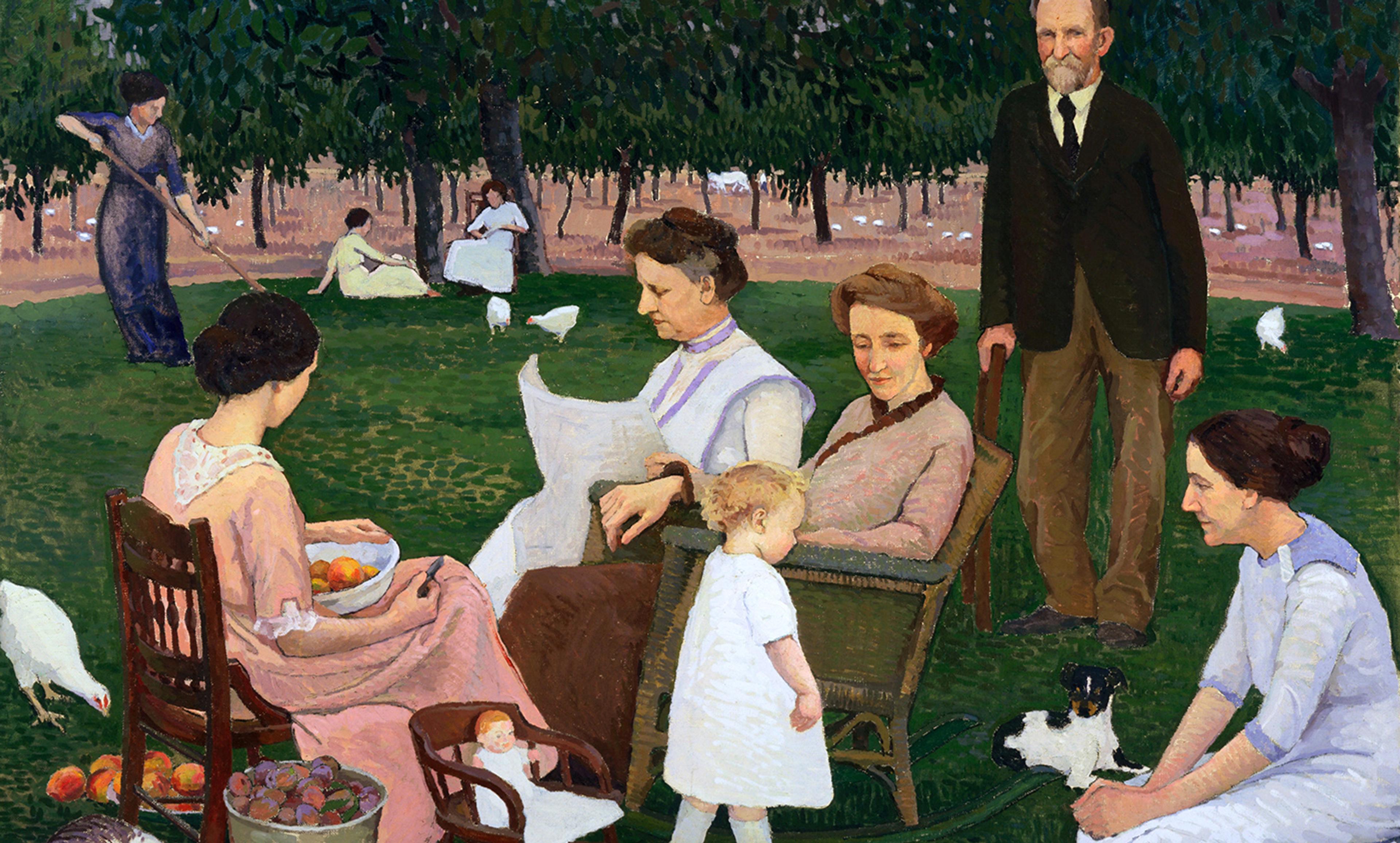

Human rights should protect our fundamental conditions for pursuing a good life. There is strong evidence that all children need to be loved in order to develop and flourish, which means that being loved is one of those fundamental conditions. This suggests that a right to be loved should be up there with rights to other pre-requisites of pursuing a good life such as the right to food, safe drinking water, shelter, health care, education, and the like.

Yet there are a number of philosophical objections to the idea that children have a right to be loved, no matter how desirable it is that they should be loved. One of the strongest such arguments can be found in Immanuel Kant’s work. Kant suggested that, since our emotions are not under our direct conscious control, it would be absurd to say that anyone had a duty to love someone else. We can’t, he believed, simply love at will, no matter how hard we try, no matter how reasonable that love would be. On this view, to claim that every child has a right to be loved would go too far, since a right implies a corresponding duty for someone to love the child, a duty that someone could be incapable of fulfilling. For Kant ‘ought implies can’: a pre-condition of having a duty in this respect is that an individual can love that child.

Still, this sort of objection is not as powerful as it first seems. It rests on the assumption that our emotions are beyond our conscious control, the assumption that we can’t choose to love someone. However, there are ways in which we can indeed bring about and cultivate parental love. First, we can give ourselves reasons to love. Thinking about why we should love a child prepares us to feel love for the child. There are excellent reasons to want to love a child since every child needs love to flourish. Secondly, we can deliberately put ourselves into situations where we are likely to feel parental love. For example, we might spend time playing with a child, or reading them a story at bedtime. We can also avoid situations that undermine our tendency to feel this love – if, for instance, I know that I am cranky when tired, I can make sure I have enough sleep when caring for the child.

By repeatedly providing reasons, and seeking out situations that make it more likely that I will feel love for my child, I can generate a disposition to love my child. So the Kantian objection that children don’t have a right to be loved because love is beyond conscious control falters. Children do indeed have a right to be loved, and those who have the primary responsibility to take care of them, that is, their parents and guardians, have a corresponding duty to love them, or at least to do everything in their power to attempt to stimulate such love.

Yet, there can be a lingering worry here. Does this mean that children who feel unloved by their parents could accuse them of denying their human rights? That might sound strange, but we should distinguish cases in which children are genuinely unloved from cases in which they are being loved but, for various reasons, don’t feel they are being loved. In the former case, the human rights of these children are indeed being denied; in the latter, it is helpful to remind ourselves that the full range of parental love involves more than just affection and warmth: sometimes it might also involve discipline. Children need discipline because, initially, they don’t know how the world works, and discipline helps to keep them safe as they learn to navigate the world. Children whose parents are loving are much more motivated to listen to them and follow rules that keep them safe. In contrast, children who are frequently punished by non-loving parents soon learn to avoid such parents.

Still, wouldn’t it be better simply to recognise that it is morally good for parents to love their children, and to try and generate that love where they don’t feel it, rather than insist on children’s right to be loved? This assumes that every child has parents, and that every parent recognises the importance of parental love for their children. However, there are millions of children in institutional care without parents. Also, child protection services receive millions of reports of abuse and neglect each year. That being loved is a right means that children in institutional care are entitled to receiving this love without having to ask for it. If children have a human right to be loved, this also implies that all of us, not just parents and guardians, have a responsibility to support policies, programmes and activities that make it more likely that every child will get the love he or she deserves and needs.