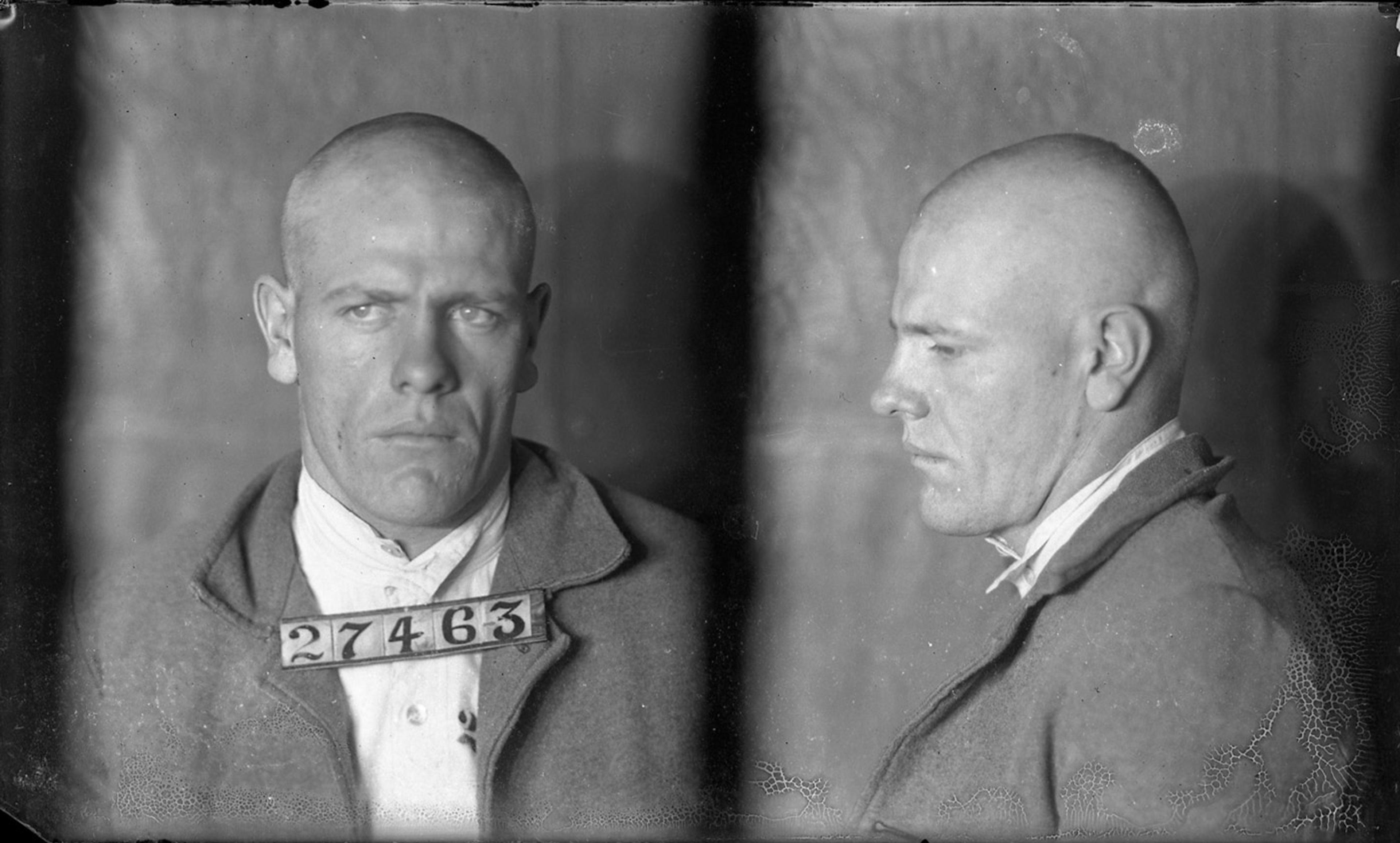

Arthur Defenbaugh, inmate #27463 photographed in 1924. Courtesy Missouri State Archives

On my first day teaching philosophy in a maximum-security prison, I stood at my classroom door, nervously waiting for my participants to arrive. As I watched the flow of men into the education department, I was immediately struck by the swagger on display. They marched down the corridor with over-developed muscles, projecting authority and machismo, hollering to their friends and acquaintances, displaying a front of the ‘hard man’ as they headed to their classrooms. However, when they entered, their demeanours changed dramatically. Their swagger would disappear as they took their seats, and looked at me with apprehension, uncertain of what was about to happen. In those early days of teaching, I discovered that prison involves survival through developing a front, or a mask to live behind. But, in reality, these men had fragile egos and complex vulnerabilities. Prison is not a place where it pays to be vulnerable.

No thinker has better encapsulated the complexities of self-presentation in a context where there is almost no place to hide than Erving Goffman. In 1957, the Canadian-American sociologist called such contexts ‘total institutions’; having done participant observation in a psychiatric hospital by feigning insanity, he knew firsthand what he was writing about, and the special pressures that come from forcible imprisonment.

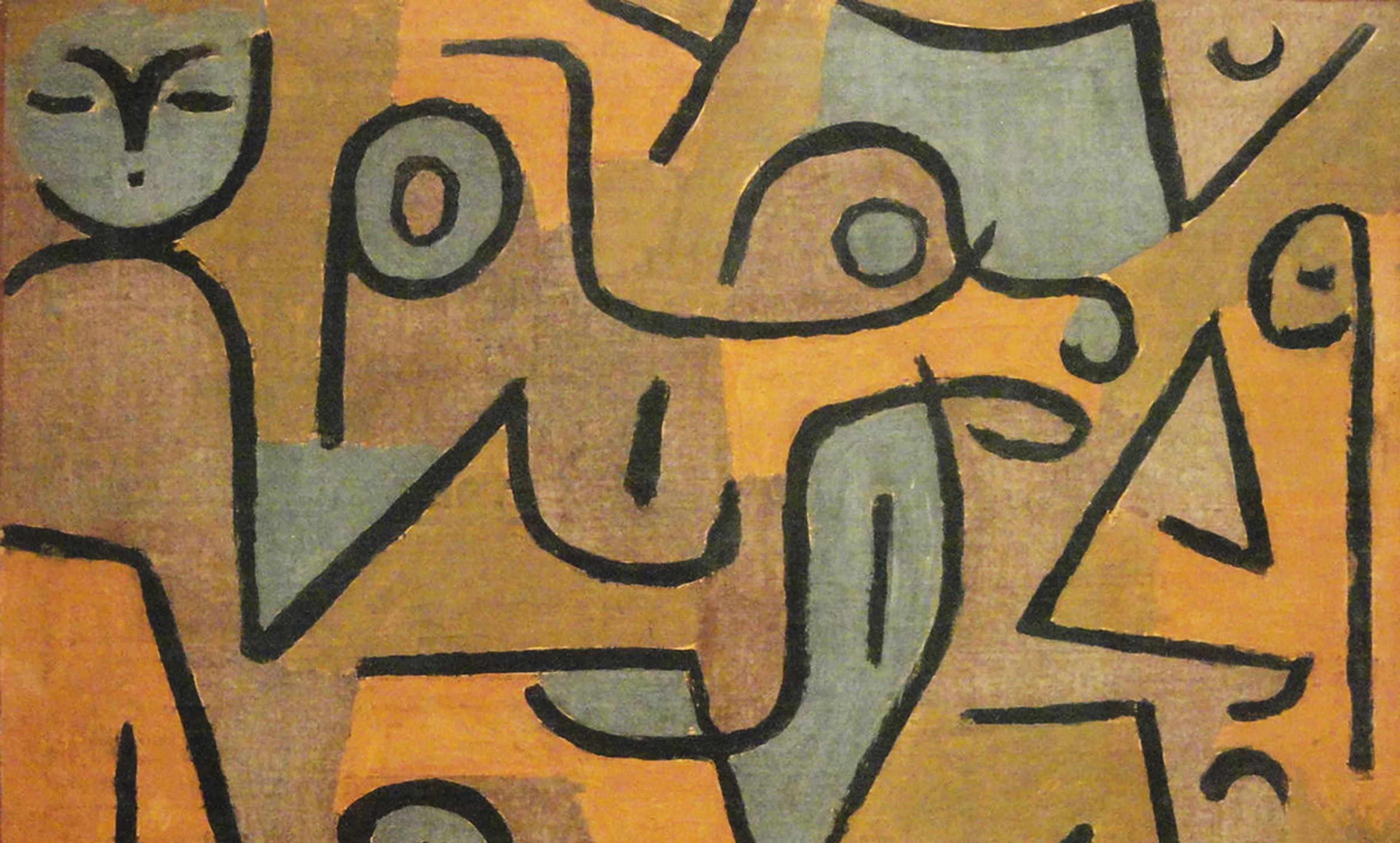

In what became a classic text, The Presentation of the Self in Everyday Life (1956), Goffman takes seriously William Shakespeare’s line that ‘All the world’s a stage,’ examining the ways in which we manage our appearance for different audiences. He explores how our identities shape, and are shaped by, the circumstances in which we find ourselves. Goffman describes identity using the metaphors of a ‘front’ and a ‘backstage’ self, which we now refer to as the ‘dramaturgical’ self. Goffman extends this metaphor by discussing how we play out various roles for the benefit of others. These roles shape how we act, and how we think about ourselves.

For those of us attempting to understand prisons and the prisoner society, Goffman’s metaphor is particularly powerful. This way of thinking about human interactions characterises the ways in which men within the prison system act towards each other, and helps to illustrate the long-term harm that can come from this. In my own research working with men in prison, Goffman’s dramaturgical self provided the foundation for articulating a distinction between ‘survival’ and ‘growth’ in this context. Specifically, it provided a vocabulary to describe how the closed institution of the prison, and the culture that develops there, affects the individual. I was interested in exploring how prison culture affects the individual’s sense of self. Goffman helped me understand the macho swagger on display in the corridor, and the change in demeanour as the classroom door closed. What I found was that prison encourages a hypermasculine ‘survival’ front that is not conducive to growth and personal development. And, without growth and personal development, our fundamental sense of self is challenged.

I’m far from the first prison researcher to reach back to Goffman’s dramaturgical metaphor of the self. For more than 50 years, prison scholars have used his theories to describe the conscious effort prisoners make to project a front in order to successfully navigate prisoner society. Given prisoners’ preoccupation with personal safety and the need to negotiate the complex and unwelcoming environment of the prison, thinking of identity in this way is helpful. However, Goffman’s theory that the ‘backstage’ self represents the individual’s ‘true’ self is, arguably, oversimplified. An individual has a range of ‘selves’ that present in different circumstances, which are not necessarily dissonant, nor are they necessarily a departure from the true self – a notion that Goffman would have questioned. Rather, they reflect different aspects of a person’s identity, with different versions of the self being allowed to come to the fore according to what is appropriate in a given social setting.

But what really happens to a person’s identity when the ‘stage’ for his performance is a prison and he must play the ‘role’ of prisoner? In prison, the ‘performance’ is one that is necessary for survival – survival of the self physically and psychologically. Prisons can be dangerous places, with a climate of distrust and threatening overtones, underpinned by a divided atmosphere. For men in prison, the survival ‘front’ typically involves developing a hypermasculine sense of self that shows no fear, emotion or distress in the face of the prison community; a kind of Stoicism that takes violence, bullying and deprivation in one’s stride, relying on no-one but oneself to get through the prison day. The prisoner role, if not performed well, carries great risk to the individual. The mask mustn’t be allowed to slip.

Importantly, Goffman discusses place and space; not only is there a front- and backstage self, there are front- and backstage areas. Frontstage areas are the places where the individual must ‘don the mask’ and ‘play the role’ assigned. Importantly, Goffman describes the backstage areas as places where the performers can relax, where they can conduct themselves more casually and engage in open conversation. Backstage areas can provide opportunity for people to create bonds, and group status can be emphasised or consolidated. These are private places, where outsiders come with caution, respectfully announcing their presence, and requesting a level of permission before entering.

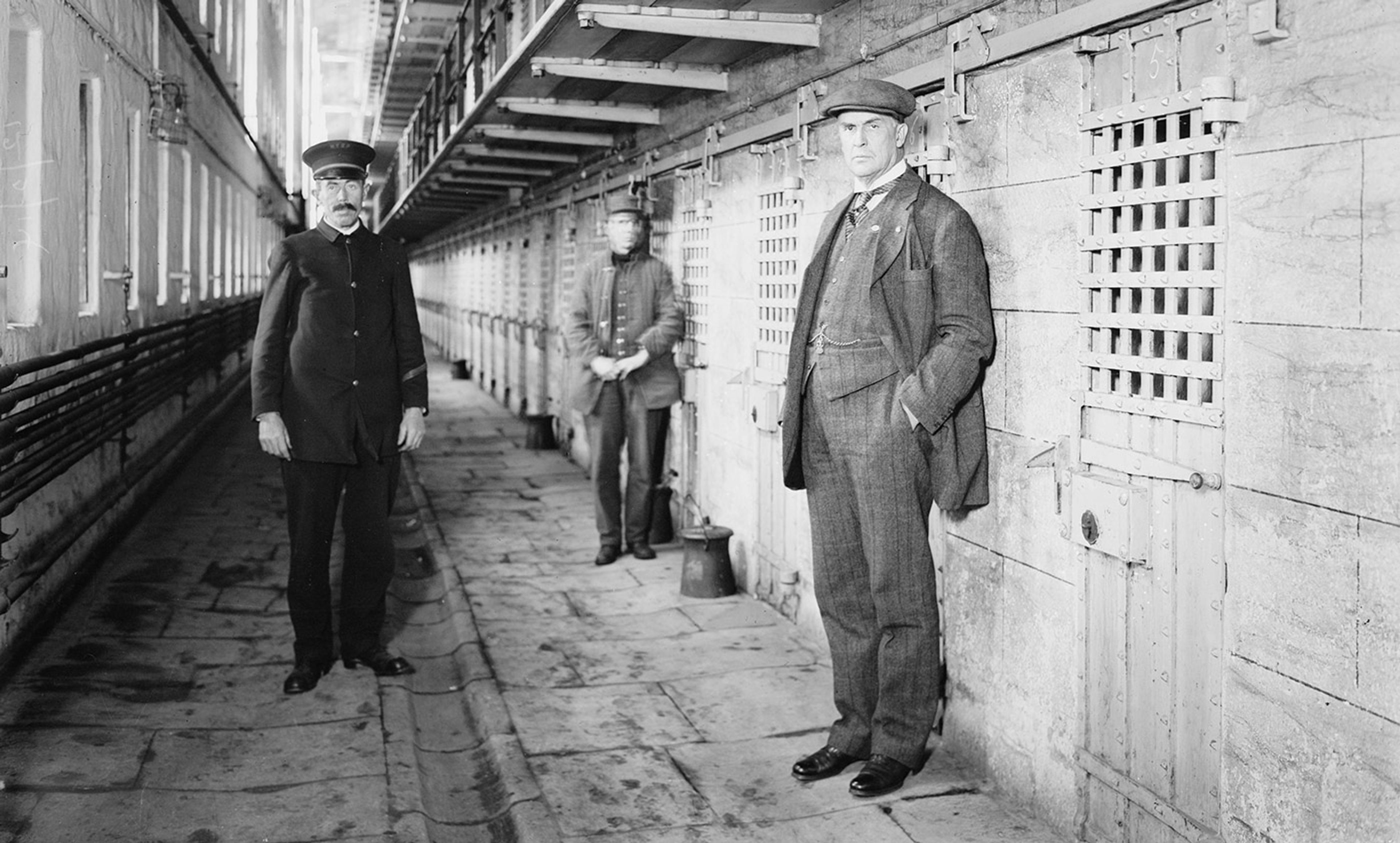

In prisons, there is no private place. Prisoners can’t relax, don’t know whom to trust, they feel watched and monitored at every turn, even when they aren’t. And even where the prisoner has the luxury of being alone in a cell, prison officers enter without permission, listen to private phone calls, and note whom they socialise with. Furthermore, the ever-present possibility of exploitation and intimidation within the prisoner community reduces the possibility of friendship or trust.

So, what happens in such places? Prisoners employ strategies to blend into the background or develop a persona (or ‘front’) as a means of achieving personal and psychological survival. These ‘fronts’ mean that true identities are suppressed, prisoners can’t be seen to being having fun or making friends within the environment, which stifles individuality or any form of self-expression. Goffman’s account gives a useful way of understanding how imprisoning people in a total institution can lead to the transformation of self, but in a way that is completely at odds with the hoped-for outcome of imprisonment: the prisoner has to maintain a ‘hard man’ mask as a matter of survival, but then he actually becomes a hard man, and leaves the prison psychologically damaged by the experience, likely to continue playing the hard-man role after release. The fear, expressed by my research participants, is that the cultivated ‘macho’ identity gradually becomes who they are, no longer a front for survival, but an expression of the fundamental self. The mask becomes the personality.