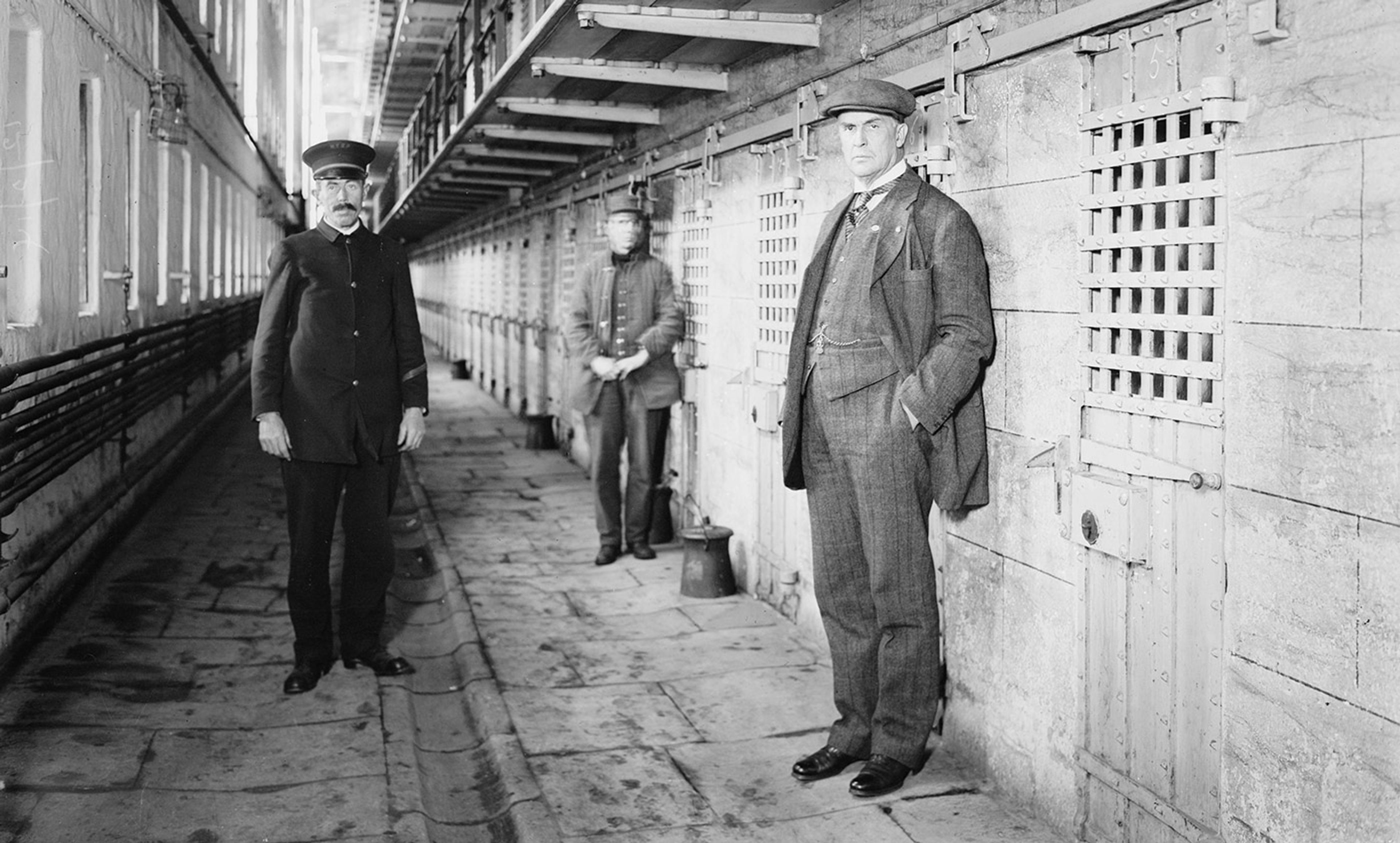

Public domain

The United States has 5 per cent of the world’s population but 25 per cent of its prisoners. Right now, 2.2 million people are locked up across the country, and while crime has been decreasing since the 1990s, rates of imprisonment are at historic highs. Americans across the political spectrum are deeply dissatisfied with this state of affairs, and agree that mass incarceration costs too much and achieves too little. But there’s also much disagreement – about the role of systemic racism, about the causes of police violence, about the importance of personal responsibility and retribution.

Nevertheless, people can find common ground on three fundamental moral norms that should govern the use of imprisonment as punishment. First, punishments should be proportional to crimes. Second, like cases should be treated alike. Third, criminal punishment should not do more harm than good. Unfortunately, the US system violates each of these principles.

Proportionality requires that the punishment fit the crime. This is more than a mere cliché. It means punishments should be neither excessive nor insufficient. Imprisonment for a parking ticket would be wrong, but so would a slap on the wrist for rape.

There’s no precise formula for proportionality, but its opposite is often easy to spot. In 2012, about 10,000 people serving life sentences in the US had been convicted for non-violent offences. Altogether, nearly 50,000 people in the US are serving sentences for life without parole; in the United Kingdom, with about a fifth the population, the number is around 50.

A major cause of the burgeoning prison population is the rise of mandatory minimum sentencing laws that force judges to hand out fixed terms for particular crimes, most often related to drugs. Such harsh punishments were endorsed by the US Supreme Court in 1991, in a case concerning a first-time offender sentenced to life without parole for possessing 672 grams of cocaine. The majority decision in Harmelin v Michigan, written by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, found that the constitutional ban on cruel and unusual punishment didn’t prohibit disproportionate sentences. (However, three of the judges who concurred with Scalia found that ‘grossly disproportionate sentences’ were not permissible, and the dissenting justices held that the Constitution does contain a proportionality requirement.)

Even if the Court was right about the Constitution, disproportionate sentences violate a basic moral principle: punishments shouldn’t exceed the severity of the crimes they address. Scalia argued that even if Harmelin’s punishment was cruel, it wasn’t unusual – and that to be unconstitutional a sentence must be both. On this interpretation, if hanging and quartering were common, it would pass constitutional muster. From a moral point of view, however, cruelty should be sufficient to prohibit a form of punishment.

A second fundamental principle of criminal justice comes from Aristotle: treat like cases alike. If two offences are similar – in their degree of seriousness or in the character and circumstances of the person who did them – they should be punished in a similar fashion. But arbitrariness and discrimination are all too common. In 1972, in Furman v Georgia, the US Supreme Court struck down existing death-penalty statutes on the grounds that they were riddled with capriciousness and inconsistency, and that they discriminated against minorities and the poor. The death penalty was put on hold throughout the US for four years, until some states reformed their statutes to meet constitutional requirements.

Obviously, unfair decisions don’t apply only to the death penalty; they exist throughout the criminal justice system. By the time an African-American man without a high-school diploma is in his mid-30s, there’s a nearly 70 per cent chance that he will have spent time in prison. Black men in the US have a higher risk of incarceration than of employment. And although five times as many white people report using drugs as African-Americans, black people are imprisoned at ten times the rate of whites. At every stage – stops, arrests, prosecutions, convictions, sentences – racial discrimination is the rule rather than the exception.

Finally, there’s the axiom that punishment must not do more harm than good. The most obvious costs of prison are monetary: the US pays around $30,000 per inmate per year, funded by billions of dollars from the federal budget. Custody is the most expensive form of punishment. This money could be used instead to treat addiction, a significant cause of criminal activity, and to improve conditions for communities where crime is endemic.

Prisons are also spectacularly ineffective at stopping crime. More than half the prisoners released in 2005 were rearrested within 12 months, according to research from 2014, and more than two-thirds were arrested by the end of their third year. A recent study by the US Sentencing Commission found that almost a third of federal offenders were reconvicted within eight years, while evidence from Texas suggests that jailing people makes them more likely to commit more serious crimes and branch out into new ones. Yet rehabilitation hasn’t been a legislated aim of US prison policy since 1984, when Congress instructed the newly formed US Sentencing Commission that ‘imprisonment is not an appropriate means of promoting correction and rehabilitation’.

Then there’s the terrible burden that incarceration places on families and communities. When someone goes to prison, 65 per cent of families find themselves unable to meet basic needs, according to the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in California. Children of jailed parents, especially young people of colour, are dramatically more likely to become homeless. In many jurisdictions, convicted felons can never vote, which means that their communities have even less of a voice than they would otherwise. And returning home after imprisonment isn’t easy. Convicted felons often struggle to find housing and employment, adding to the worries of their already-stressed families.

Some jurisdictions have adopted ‘ban-the-box’ policies that forbid employers from requiring applicants to indicate if they have a criminal record. But even these well-intentioned regulations can backfire. A recent experiment by the economist Amanda Agan and the legal scholar Sonja Starr found that ban-the-box policies in New York and New Jersey made employers more likely to discriminate against black jobseekers – seemingly because a lack of information about criminal convictions makes people more likely to judge applicants with characteristics (such as being African-American) that are statistically associated with higher rates of crime.

You might acknowledge the costs of imprisonment but think they’re outweighed by the benefits. One possible benefit is ‘general deterrence’: the idea that would-be offenders are less likely to commit crimes because of the prospect of punishment. (We have already seen that those convicted of crime have high rates of recidivism; this is the province of ‘specific deterrence’.) But it’s unlikely that mandatory or severe penalties have a greater deterrent effect than milder sentences, according to Michael Tonry, a leading scholar of criminal justice, on the basis of his analysis of data and projections between 1975 and 2025. These findings are in keeping with the criminological maxim that it’s not the severity but the certainty of punishment that deters people.

You could point to a different justification for punitive policies: the moral necessity of retribution. The philosopher Immanuel Kant argued that punishment rights the scales of justice that the criminal has tilted out of whack. The idea is that criminals deserve to suffer for what they have done, and that not to punish them is intrinsically wrong. Most people intuitively find this view at least somewhat persuasive, in no small part because of the retributive impulses we find lurking within ourselves. But there are at least three reasons to question whether we should act on these feelings.

First, many people who commit crimes have themselves suffered from deprivation, injustice, abuse, addiction, and mental illness. Morally, we cannot reduce people to the sum of their heredity and environment. But there’s no denying that luck plays a large role in people’s circumstances and whether they commit crimes, and that these contingencies should mitigate the pain we inflict on offenders whenever possible.

Second, there’s the possibility of remorse and transformation. Retribution seems to imply that criminals must always be identified with their worst behaviour. Of course, not everyone will experience sincere changes of heart. But to insist that offenders can do nothing to redeem themselves is both irrational and immoral.

Finally, there’s the radical utilitarian argument first advanced by Cesare Beccaria and Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century, which claims that all pain is bad – even the pain of a wrongdoer. It follows from this view that inflicting harm can be justified only to prevent something worse, and so retribution for its own sake has no part to play in a fair system of justice.

Even those who reject this radical view – who believe that retribution does have a place in the machinery of criminal justice – should agree that it cannot justify the evils we find in US prisons today. The system’s gross lack of proportionality, its failure to treat like cases alike, and its harmful consequences for prisoners and communities are incompatible with a humane and decent society.