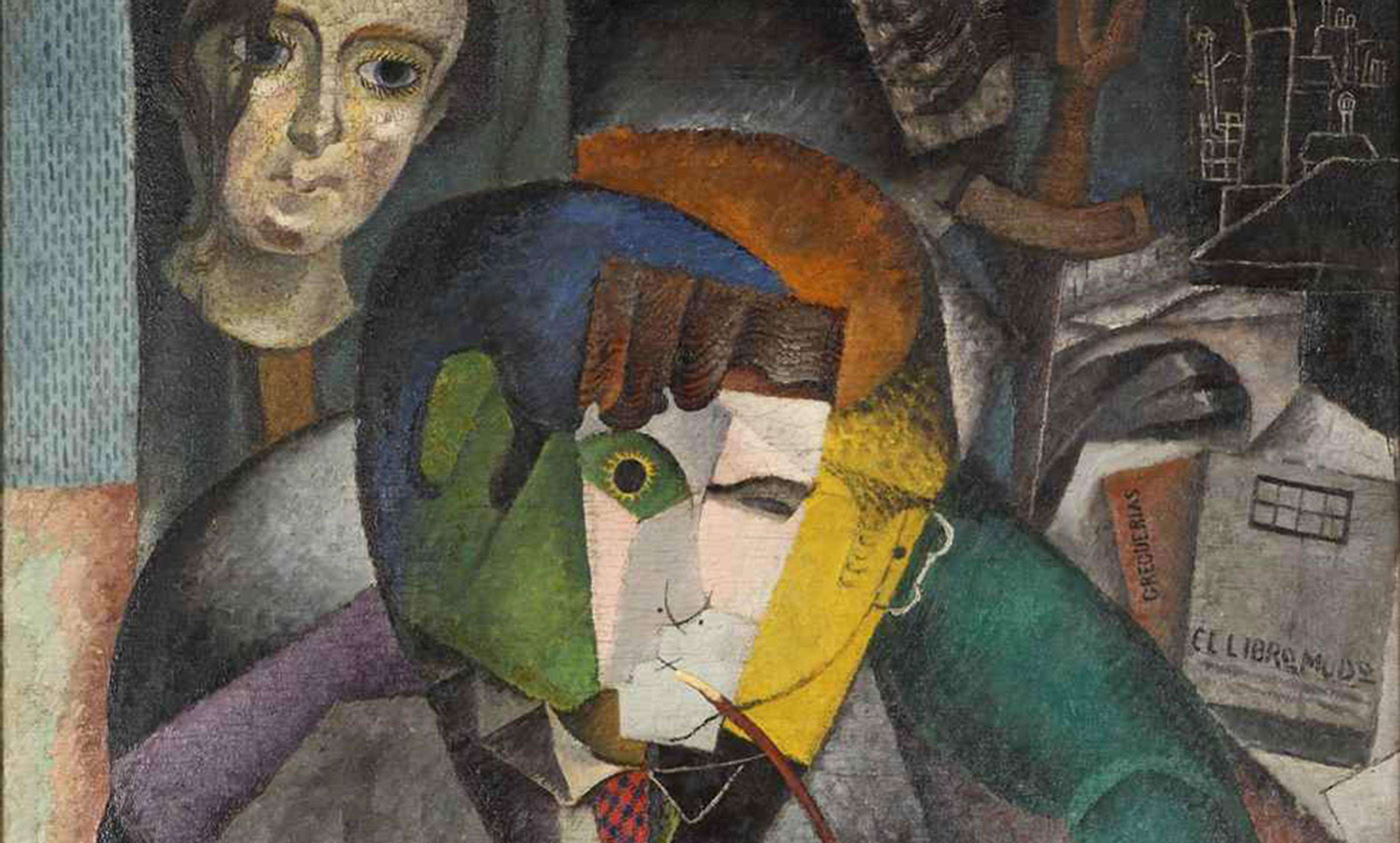

Brain work. Office clerks, United States, 1915. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Work is hard. But we don’t always realise how hard it is or, indeed, that some forms of labour are work at all. If you stand on your feet or stare at a screen all day, you can point to bodily strain. But if a task is something more mental, the difficulty is often invisible – which can make it hard to evaluate or celebrate those who perform such tasks.

Jobs defined by their cognitive contributions tend to gain attention when other forms of labour are perceived as threatened. Anxieties about being innovated out of a job or being replaced by machines tend to bring into focus those skills and states of mind that are irreducibly human. No job is physical or mental alone, of course. But cognition plays a special role in how work is valued. Take ‘emotional labour’: historically underpaid jobs in care industries held mostly by women. Recognition of emotional labour has grown alongside fears of automation in other areas of the economy.

This is not the first time mental labour has gained new recognition in a changing employment landscape. A century ago, a similar transformation produced another new cognitive category. Concerns about the future of work led to a re-appraisal of the difficulty of existing jobs. Specifically, a growing perception that new technologies threatened manual labour on farms and in factories led some to look to more sedentary positions – in offices and at desks – as the way of the future for those displaced.

It was not all rosy, however. Some of the first to identify these changes in the workplace were physicians, who expressed growing alarm about the surprising physical and mental effects of this kind of cognitive labour. What seemed, to the outside, like a step up in the workforce was being decried as sneakily arduous, even dangerous.

Doctors called these jobs ‘brain work’, and argued that they taxed those who did them even more than manual trades. A desk job could be just as dangerous as one on the factory floor. In making their case, physicians gave ‘brain workers’ a way to legitimate their labour as arduous and, crucially, human. Their definition and defence of ‘brain work’ paved the way for today’s treatment of emotional labour as the path forward in an age of increasing automation.

The category of ‘brain work’ was suited to the Gilded Age of the 1870s-1900s. As a new label for cognitive tasks, it wedded ongoing changes in the science and medicine of the mind to fears about technological developments that were impacting on the nature of work. Medicine and machinery, cognition and capitalism – this was the intersection at which important features of human nature and its relationship to productive labour were redefined.

In the late-19th century, the theory of ‘nervous energy’ explained how the mind and brain interacted – for better and for worse. Too much nervous energy made you excitable, while too little left you drained. The American neurologist George Miller Beard popularised the idea of ‘neurasthenia’ to explain what he saw as an American malady: the rapidity and constant stimulation of the modern world was leading to nervous exhaustion.

The cause, according to Beard and others, was the pace of technological change, which they saw as unprecedented – and dangerous. This was the context in which ‘brain work’ first appeared. It helped both to explain how office workers were as exhausted as factory workers and to celebrate a form of labour that contemporaries felt was safe from becoming obsolete.

Medical accounts of nervous exhaustion and mechanical advances in the manufacturing sector conspired to put ‘brain work’ on the map. Those who worked with their brains now had a story to tell about their burnout and a sense that the jobs that were causing it were safe – for now.

It’s a strange sort of comfort, if you think about it. ‘Brain work’ made us human, according to its proponents, but it was also killing us. Looking back, it seems like the mandate to safeguard human exceptionalism won out over addressing the health consequences of cognitive labour.

The same is true of emotional labour today. Advances in the science and medicine of mind-brain connections have taken an ‘affective turn’, acknowledging both the positive and the negative dimensions of emotions in social life and personal wellbeing. Affective neuroscience is now central to how we understand identity and interaction. Ours is an affective age.

At the same time, new anxieties about technology’s impact on labour have us searching for tasks that robots and artificial intelligence can’t do.

These two transformations, the affective turn and artificial intelligence, have converged on ‘emotional labour’. Psychiatrists and others are highlighting just how taxing, how hard, this kind of work can be. Whether it’s in the care industries or at home, emotional labour has long been associated with women – which is a major reason why it has been overlooked for so long. Today, in the face of technological change, it’s being held up as the one form of work that’s safe from automation.

Emotional labour is to artificial intelligence as ‘brain work’ was to the mechanisation of factories: both are ways of using science and medicine to celebrate certain kinds of work. Cynically, one could point out that in both cases the recognition took hold only when manufacturing jobs were threatened and men sought validation for new lines of work. But if that means recognising work that’s long been undervalued, it might be okay.

The real risk is that companies might now try to outsource emotional labour rather than do it in-house – just like they did with ‘brain work’. The rise of management consulting a century ago was one upshot of the advent of ‘brain work’. What might the equivalent development be for emotional labour – and will it be an unalloyed good?