888bailbond/Flickr

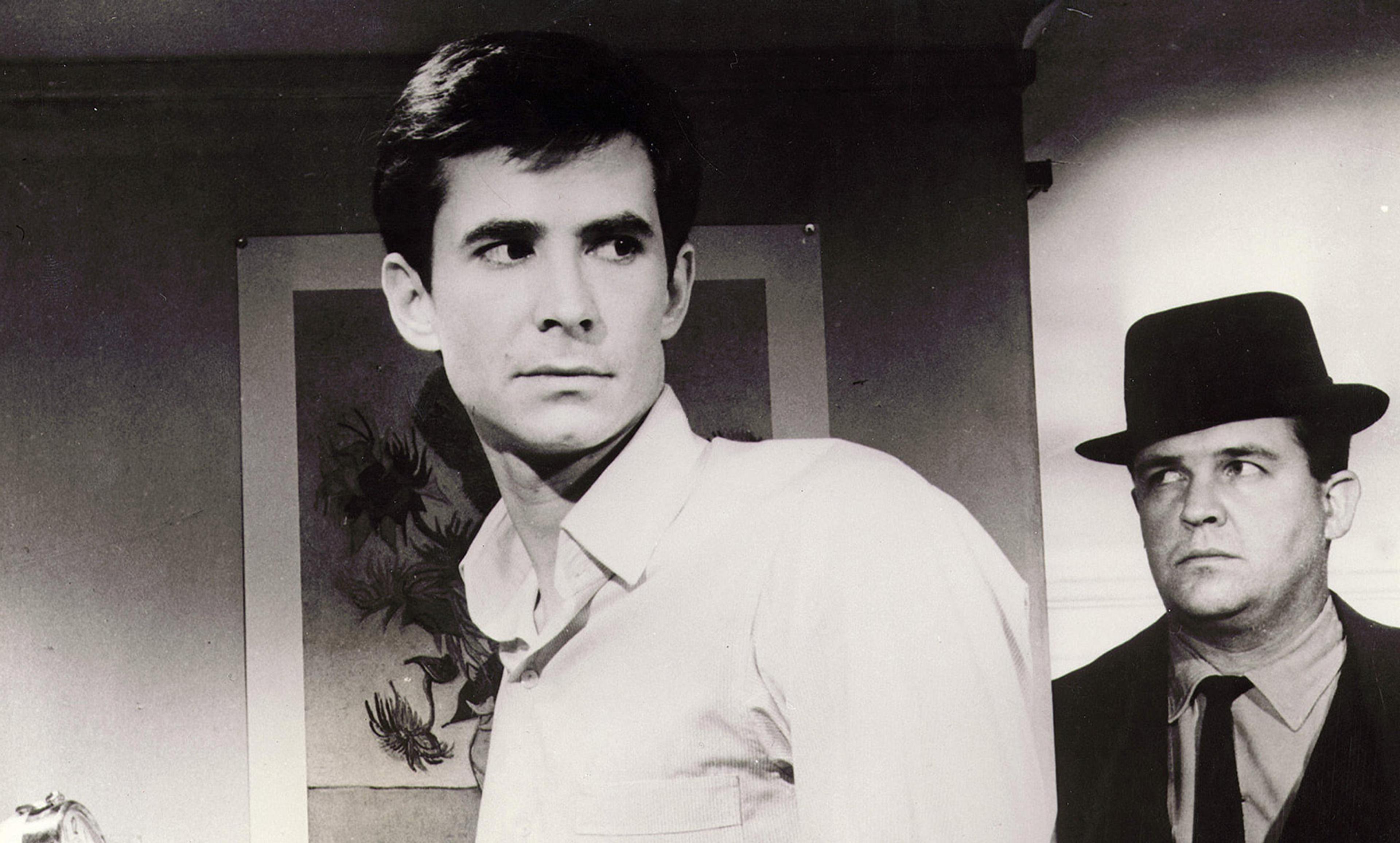

If you were among the millions of people who watched the Netflix series Making a Murderer (2015), you were probably disturbed by the scenes of police interrogating Brendan Dassey, a 16-year-old mentally challenged boy. You would have seen the detective Mark Wiegert pressuring Dassey – guiding his choices, subtly feeding him information – until he admits to helping his uncle rape and slaughter magazine photographer Teresa Halbach in 2005. It’s clear that the boy will say just about anything just to get out of that room.

That disturbing interrogation, while an extreme example, is standard operating procedure in many police departments in the United States and in the security branches of many international corporations. They learn the Reid Technique – a step-by-step interview process that purports to train ‘human lie detectors’, who unerringly arrive at truthful confessions. But that claim can’t possibly be true.

How I do I know? Because I am a Reid-certified interrogator.

The Chicago-based John E Reid & Associates Inc is the Walmart of interrogation training. The company produces textbooks on interrogation and trains thousands of public and corporate security officials each year, according to the its website. Developed in the late 1940s by the ex-cop and polygraph expert John E Reid (and modified many times over the years), the technique is loosely based on the assumption that body language reveals whether a person is lying, and that a deceptive person will show signs of anxiety. Psychologists have spent decades disproving those assumptions but the method remains the gold standard in interrogation training.

A few years ago, as part of a journalistic investigation, I signed up for their three-day course to witness the training first-hand.

What I experienced seemed like nothing so much as a seminar in pseudo-science. Our instructor spent a lot of time teaching us how to read body language to tell when a suspect is deceptive, even though psychologists know there’s no such connection. He taught us that, once we determined that the suspect was lying, we should cling to that impression and move boldly ahead – a well-known mistake that psychologists call ‘confirmation bias’, in which we unconsciously seek evidence to confirm our beliefs. We also learned how to ratchet up the discomfort level associated with denial, and how to make it more appealing to confess. We were taught how to ask multiple-choice questions rather than open ones, which inevitably steers and distorts recollections.

Most disturbingly, we were taught that it’s legal in the US to lie to suspects about evidence, albeit as a last resort. It’s a tactic that psychologists have shown can break down resistance and lead to a confession, accurate or not. Detective Wiegert got results when he kept fibbing to Brendan: ‘We know you did it.’ So did the detectives who in 1988 arrested Martin Tankleff, a teenager from Long Island, New York, after he found both his parents dying of stab wounds on the kitchen floor. Police interrogated him for many hours without result. They finally got the confession they needed when they made up a story that, moments before dying, Martin’s father identified his son as the killer. It took 17 years to get the innocent young man out of jail.

These tactics effectively elicit confessions; but as many studies show, they also create false ones. And as coercive as they are with adults, they’re even more so with juveniles.

That’s what we saw during the interrogations in the documentary: a detective who is dead-certain of his intuition, bearing down on a vulnerable young man. Wiegert was a Reid-certified interrogator – he testified to that fact during Dassey’s trial in 2007. When asked by the prosecutor to support his credibility, he called upon Joseph Buckley, president of the Reid Company. Buckley viewed the interrogation videos and wrote a report concluding that the detective acted ‘with the appropriate standard of care and did follow the standards of accepted practice’.

To be fair, in recent years Buckley has testified that the kind of high-pressure tactics portrayed in the documentary stray beyond what his company considers acceptable. The company also cautions that care must be taken when interrogating juveniles, who are highly suggestible. Yet I don’t find that entirely reassuring. The basis of the company’s technique has not changed. And Reid is now reaching into new areas, offering seminars and online training courses for school administrators who wish to interrogate their students.

In the early 1990s, the Home Office in the United Kingdom, in the wake of several false-confession scandals, rejected Reid-style accusatory interrogations and mandated informational interviewing instead. This method relies on open-ended questions and an objective analysis of the content of the interview rather than the subject’s emotional affect. It’s time all the US police departments follow the UK’s lead. Pseudo-science has no place in criminal investigations.