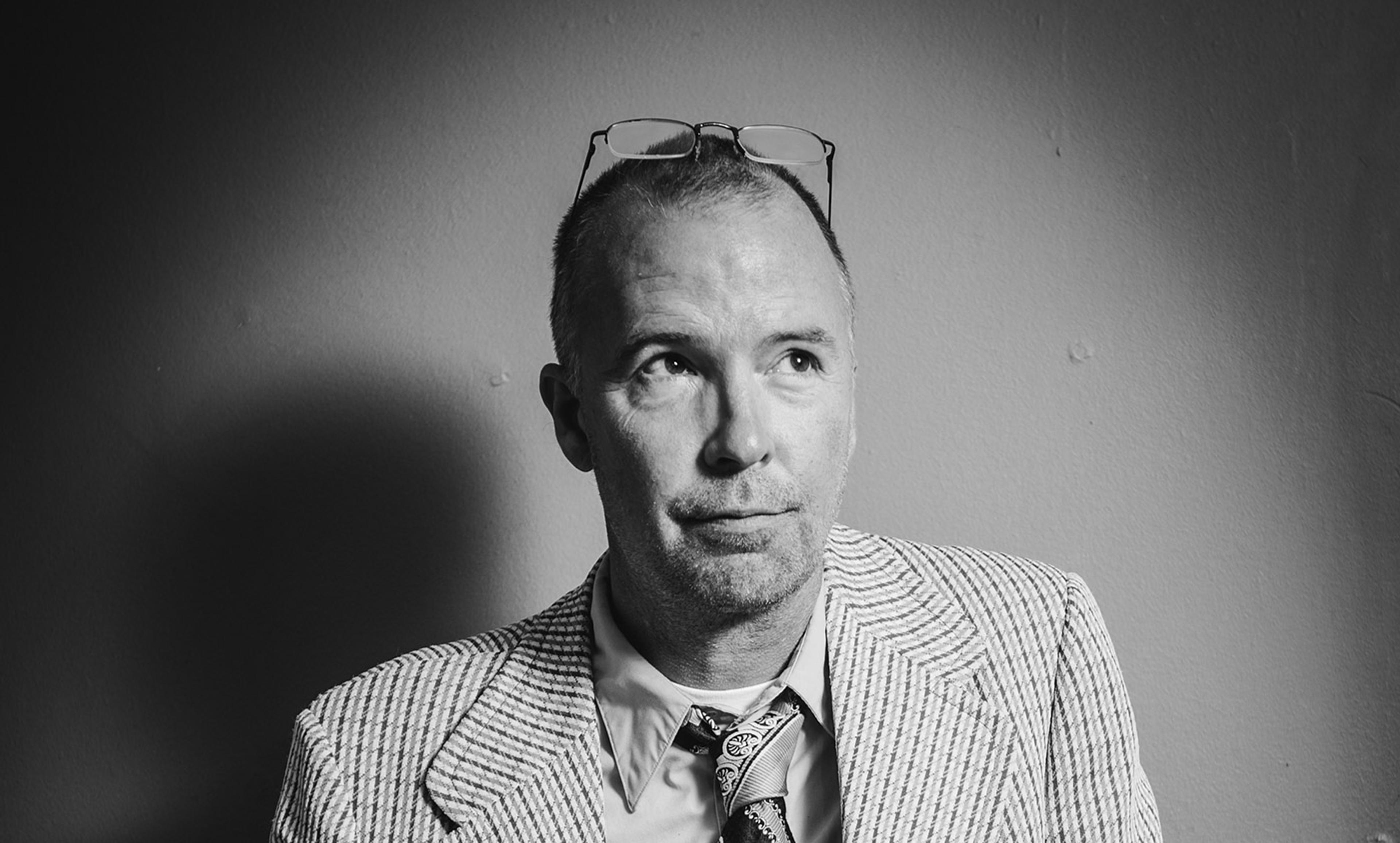

Ha ha ha …very good. Joseph Stalin in 1949. Photo by Sovfoto/Getty

Stalinism. The word conjures dozens of associations, and ‘funny’ isn’t usually one of them. The ‘S-word’ is now synonymous with brutal and all-encompassing state control that left no room for laughter or any form of dissent. And yet, countless diaries, memoirs and even the state’s own archives reveal that people continued to crack jokes about the often terrible lives they were forced to live in the shadow of the Gulag.

By the 1980s, Soviet political jokes had become so widely enjoyed that even the US president Ronald Reagan loved to collect and retell them. But, 50 years earlier, under Stalin’s paranoid and brutal reign, why would ordinary Soviet people share jokes ridiculing their leaders and the Soviet system if they ran the risk of the NKVD (state security) breaking down the door to their apartment and tearing them away from their families, perhaps never to return?

We now know that not only huddled around the kitchen table, but even on the tram, surrounded by strangers and, perhaps most daringly, on the factory floor, where people were constantly exhorted to show their absolute devotion to the Soviet cause, people cracked jokes that denigrated the regime and even Stalin himself.

Boris Orman, who worked at a bakery, provides a typical example. In mid-1937, even as the whirlwind of Stalin’s purges surged across the country, Orman shared the following anekdot (joke) with a colleague over tea in the bakery cafeteria:

Stalin was out swimming, but he began to drown. A peasant who was passing by jumped in and pulled him safely to shore. Stalin asked the peasant what he would like as a reward. Realising whom he had saved, the peasant cried out: ‘Nothing! Just please don’t tell anyone I saved you!’

Such a joke could easily – and in Orman’s case did – lead to a 10-year spell in a forced-labour camp, where prisoners were routinely worked to death. Paradoxically, the very repressiveness of the regime only increased the urge to share jokes that helped relieve tension and cope with harsh but unchangeable realities. Even in the most desperate times, as the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev later recalled: ‘The jokes always saved us.’

And yet, despite these draconian responses, the regime’s relationship with humour was more complicated than we tend to assume from the iconic narratives we’ve long internalised from George Orwell’s novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s memoir The Gulag Archipelago (1973).

The Bolsheviks were certainly suspicious of political humour, having used it as a sharp weapon in their revolutionary struggle to undermine the tsarist regime prior to their dramatic seizure of power in 1917. After they consolidated their position, the Soviet leadership warily decided that humour should now be used only to legitimise the new regime. Satirical magazines such as Krokodil therefore provided biting satirical attacks on the regime’s enemies at home and abroad. Only if it served the goals of the revolution was humour considered useful and acceptable: as a delegate to the Soviet Writers’ Congress of 1934 summed up: ‘The task of Soviet comedy is to “kill with laughter” enemies and to “correct with laughter”’ those loyal to the regime.

Nevertheless, while many Soviet people no doubt found some comic relief in these state-sanctioned publications, humour can never be entirely directed from above. In the company of friends, and perhaps lubricated with a little vodka, it was frequently nigh-on impossible to resist taking things several steps further and to ridicule the stratospheric production targets, ubiquitous corruption and vast contradictions between the regime’s glittering promises and the grey and often desperate realities ordinary people encountered daily.

Take, for example, the gallows humour of Mikhail Fedotov, a procurement agent from the Voronezh region, who shared a common anekdot that laughed at the true costs of Stalin’s uncompromising industrialisation drive:

A peasant visits the Bolshevik leader Kalinin in Moscow to ask why the pace of modernisation is so relentless. Kalinin takes him to the window and points at a passing tram: ‘You see, if we have a dozen trams at the moment, after five years we’ll have hundreds.’ The peasant returns to his collective farm and, as his comrades gather around him, clamouring to hear what he’s learnt, he looks around for inspiration and points to the nearby cemetery, declaring: ‘You see those dozen graves? After five years, there will be thousands!’

Such a joke could relieve oppressive fears by making them (briefly) laughable, helping people share the enormous burden of a life lived – as another quip ran – ‘by the grace of the NKVD’. But even as it helped people to get on and get by, sharing an anekdot became ever more dangerous as the regime grew increasingly paranoid over the course of the 1930s. With the threat of war looming over Europe, fears of conspiracy and industrial sabotage ran amok in the USSR.

As a result, any jokes that criticised the Soviet political order rapidly became tantamount to treason. From the mid-1930s onwards, the regime came to see political humour as a toxic virus with the potential to spread poison through the arteries of the country. According to a directive issued in March 1935, the telling of political jokes was henceforth to be considered as dangerous as the leaking of state secrets – so dangerous and contagious, in fact, that even court documents shied away from quoting them. Only the most loyal apparatchiks were permitted to know the contents of these thought crimes, and joke-tellers were sometimes prosecuted without their words ever being included in the official trial record.

Ordinary people had little chance of keeping pace with the regime’s paranoia. In 1932, when it was more risqué than dangerous to do so, a railway worker such as Pavel Gadalov could crack a simple joke about Fascism and Communism being two peas in a pod without facing serious repercussions; five years later, the same joke was reinterpreted as the tell-tale sign of a hidden enemy. He was sentenced to seven years in a forced-labour camp.

This style of retroactive ‘justice’ is something we can recognise today, when the uncompromising desire to make the world a better place can turn a thoughtless Tweet from 10 years ago into a professional and social death sentence. This is a far cry from the horrors of the Gulag, but the underlying principle is eerily similar.

However, like many of us today, the Soviet leaders misunderstood what humour is and what it actually does for people. Telling a joke about something is not the same as either condemning or endorsing it. More often, it can simply help people point out and cope with difficult or frightening situations – allowing them not to feel stupid, powerless or isolated. In fact, something the Stalinist regime failed to appreciate was that, because telling jokes could provide temporary relief from the pressures of daily life, in reality it often enabled Soviet citizens to do exactly what the regime expected of them: to keep calm and carry on.

When we tell jokes, we are often simply testing opinions or ideas that we are unsure of. They are playful and exploratory, even as they dance along – and sometimes over – the line of official acceptability. The vast majority of joke-tellers arrested in the 1930s seemed genuinely confused to be branded enemies of the state due to their ‘crimes’ of humour. In many cases, people shared jokes criticising stressful and often incomprehensible circumstances just to remind themselves that they could see past the veil of propaganda and into the harsh realities beyond. In a world of stifling conformity and endless fake news, even simple satirical barbs could serve as a profoundly personal assertion that ‘I joke, therefore I am.’

We laugh in the darkest times, not because it can change our circumstances, but because it can always change how we feel about them. Jokes never mean only one thing, and the hidden story of political humour under Stalin is far more nuanced than a simple struggle between repression and resistance.