Alberto Otero Garcia/Wikipedia

The United Nations Climate Change Conference that took place in Paris in 2015 engendered a new global commitment to clean energy and reinvigorated discussion of nuclear power as a solution to climate change. It’s low-carbon. It’s technology we have. And political and economic support can be found among the elite. Yet, this turns a blind eye to nuclear power’s health legacies, seen most clearly in rural uranium communities, where the technology continues to make residents ill well after the Second World War and the Cold War ended. Individuals in hundreds of such communities share similar experiences but lack the power to tell their stories. Yet the stories demand to be heard, and the tellers need help for the unsustainable damage they and their communities endure – the very communities poised to produce much of the uranium needed to fuel a nuclear renaissance.

In fact, the $54 billion-worth of United States federal loans pre-approved for subsidised nuclear reactor construction should also fund cancer screening and treatment facilities in affected communities. If the government funds nuclear power as a renewable energy source near these communities, as is currently occurring in the state of Utah, then monies should also go toward sustainable community development. Funds could support programmes to counter poverty caused by resource extraction; shape comprehensive uranium and nuclear regulatory policies with teeth; develop emergency evacuation and exposure plans in communities hosting risky production or waste-storage facilities; and create healthcare sub-systems that help to address community-wide cancer clusters and industry costs currently thrust on individual households.

Though few Americans have heard of it, the uranium community of Monticello in Utah played a strategic role in the Second World War, the Manhattan Project, and the Cold War – and showcases unaddressed environmental injustices of state-led nuclear programmes. The Monticello Mill Tailings, nestled against residential streets, was one of only 11 Second World War-era uranium mills, and the only mill owned by the US government for the duration of its operation. Even as the Monticello mill closed its doors in 1960, residents identified leukemia clusters among adolescents. For decades, four radioactive tailings piles remained uncovered on the former mill site, serving as a playground for children and providing hundreds of thousands of tons of building materials for Monticello’s street foundations, sub-basements, and other construction projects. The federal government knew about the risk, but failed to warn the community.

By the early 1990s, two federal Superfund sites were declared in Monticello. As the $250-million Environmental Protection Agency remediation ensued, residents noticed many cases of cancer, persistent respiratory problems, reproductive issues, universal allergies, or children with birth defects – and they linked them to community-wide, long-term uranium exposure. But the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry contested these claims. It still does. Consequently, the Victims of Mill Tailings Exposure organised in 1993, working to establish a community cancer-screening and treatment facility, and gain federal reparations to cover medical expenses. But 20 years later, activists have received little recognition and no formal response.

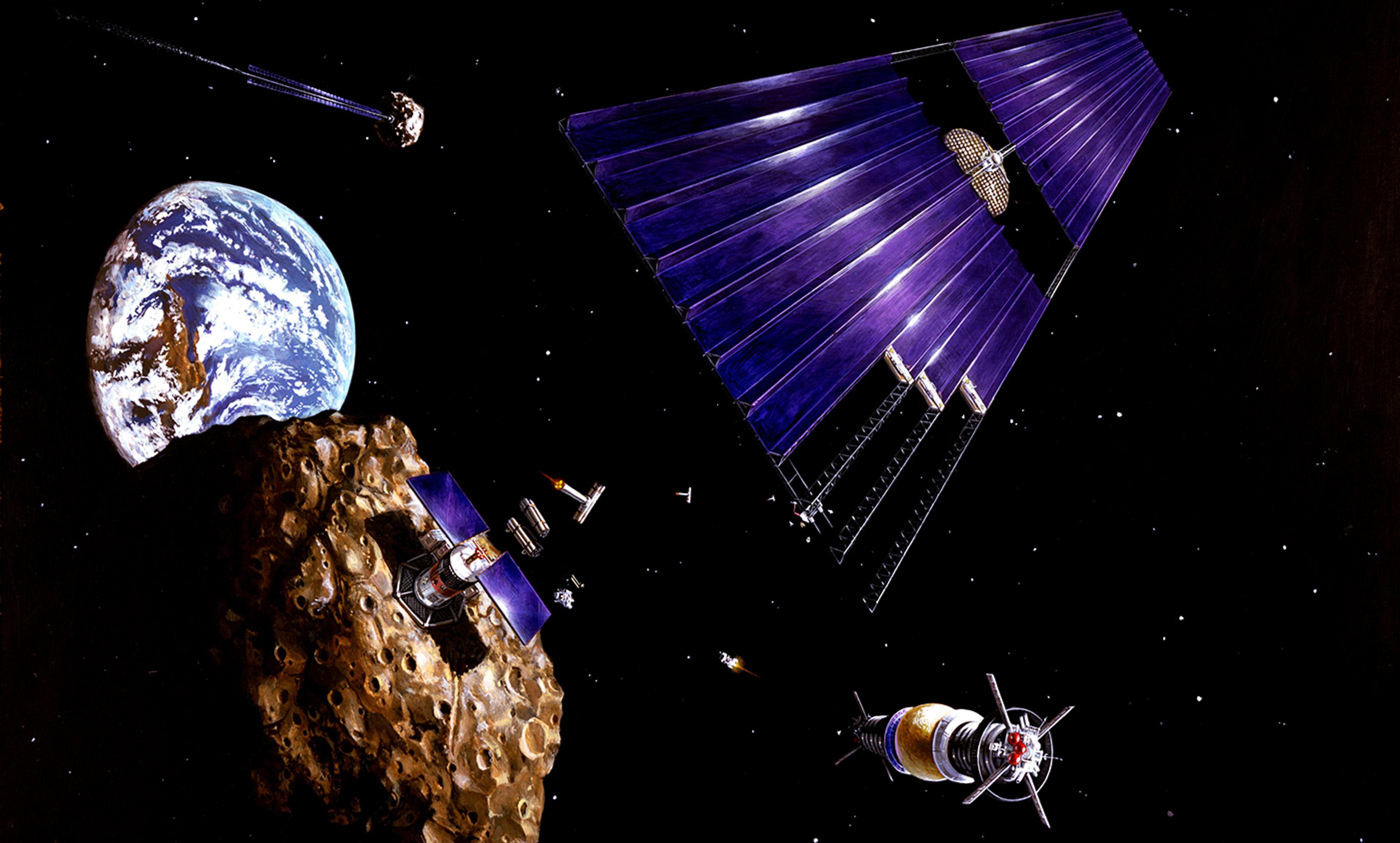

Yet health is just part of the problem. Nuclear power carries a host of other persistent socio-economic issues. Nuclear power production depends on global uranium and energy markets on one end, and is dogged by seemingly endless debates over waste storage and the siting of power stations on the other. The industry is also prone to economic volatility and instability, especially in the early stages, when ore is extracted from the ground. Communities ride the waves: brief, glittering moments of booming development, followed inevitably by persistent, town-killing busts and chronic, debilitating poverty for those who stay. Tension divides communities as residents argue over the meaning of development and environmental justice.

Again, uranium communities are illustrative. In 2011, Energy Fuels Resources Inc secured a permit to construct the Piñon Ridge Mill in southwestern Colorado. It was no small feat: this was the first uranium mill permitted in the US in almost 30 years. Even without being built, the mill became a lightning rod. Vicious public debate erupted, pitting impoverished towns such as Nucla and Naturita against wealthier communities such as Telluride. While southwestern Colorado had nurtured fledgling energy partnerships – ventures such as community-based solar cooperatives – many of these were scrapped or delayed as tensions mounted over renewed uranium production. Instead of inspiring regional collaboration, division over uranium production devolved into death threats and class wars. Hardly a firm foundation for energy development practices that can be sustained over time.

As we discuss potential solutions to mitigate the impact of climate change, we must also stop tiptoeing around the dense network of places, spaces and people affected by nuclear technology in the past. We owe it to uranium communities to recognise and formally address their experiences before boldly considering nuclear power as a sustainable, renewable policy solution to combat climate change.