Douglas Scortegagna/Flickr

I had just finished digging an outhouse pit on a river in Colorado with a fellow National Park Service ranger when we saw the unexpected: a solo kayaker paddling the rapids that ran past our camp. A law-enforcement ranger who’d been leaning on a shovel had gotten a better look. He pulled out his two-way radio to call a backcountry station 45 miles downstream. ‘Lone kayaker passing Anderson Hole at 1930 hours,’ said the ranger-cop. ‘He’s headed your way.’

All boaters approved to launch that day had already gone by. The kayaker had put on the water without a permit – breaking a cardinal rule of boating in the national monument. He hadn’t counted on passing our raft patrol, and simply kept going in hopes that we wouldn’t give chase.

He knew that he was breaking the rules, and he isn’t alone. When I asked several dozen friends of all backgrounds why they break the rules outdoors, a third said that they never had. The other two-thirds admitted to going beyond a marked boundary, entering a protected area without a permit, or walking a leashed or unleashed pet in a restricted area. Some said they’d ignored mandatory safety regulations or gone into a natural area closed to all entry.

Research on why we break rules points to a range of reasons. We might want to experience a cheater’s high, the good mood that follows getting away with a transgression. Or we might believe our infractions won’t hurt anyone. Most of the outdoor rule-breakers I quizzed said they’d chosen to break rules that made no sense, or because others had, or because the consequences of their actions wouldn’t be significant.

Research shows, however, that our actions can have bigger impacts than we know. The mere presence of domestic dogs, for instance, is known to drive wildlife from protected areas. A Colorado State University study showed significantly fewer mule deer, small mammals, prairie dogs and bobcats in habitats where dogs were allowed. Similarly, allowing dogs to chase birds triggers their flight, and diverts time and energy from feeding, resting or tending young.

For those participating in snow sports such as skiing, crossing forbidden boundaries poses risks to other people, infrastructure and the environment. The Utah Avalanche Center notes that most avalanche fatalities are triggered by people unaware of the risks involved in going out of bounds: among its many examples, the Center cites a skier-triggered avalanche near Jackson Hole, Wyoming, the worst in 100 years, which buried a creek 20 to 30 feet in debris. Out of sheer luck, no people were hurt.

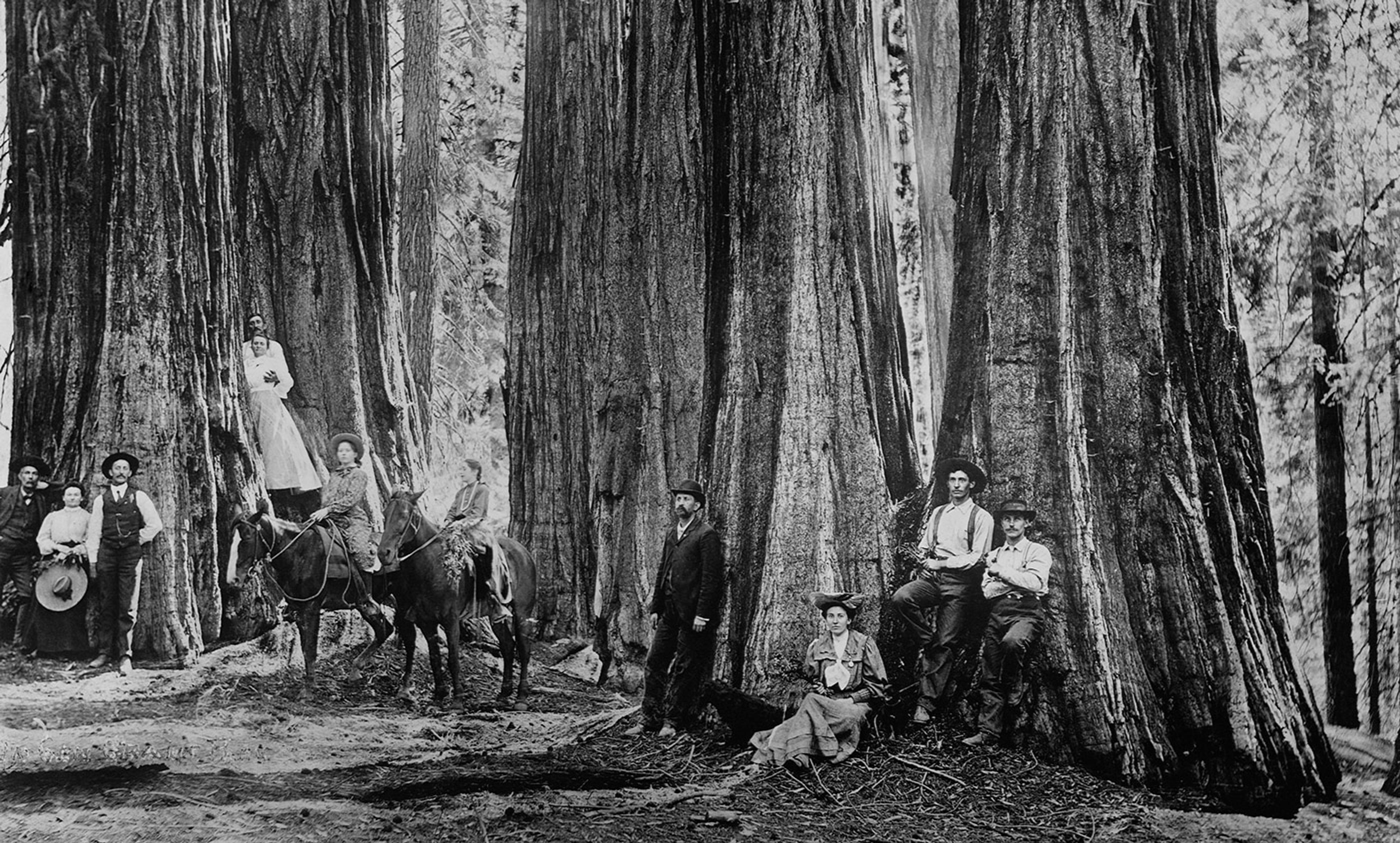

Most people just don’t understand the fragility of park environments or the wildlife they contain. ‘Take the rules about bears in Sequoia National Park,’ says Jeannine Koshear, a former State Park ecologist and National Park backcountry ranger. ‘They protect the bears from visitors and the visitors from bears. The rules are not just for the sake of making rules.’

Yet, like the birds, humans venturing outdoors are making their own sort of flight, based on the need for space from other visitors. One friend said: ‘I didn’t go into the wilderness to stay on a marked trail, to time myself between mile markers, or to compare outdoor gear with fellow hikers.’ Many also want to be free of outside control: ‘Going somewhere alone was the goal – to go off trail, into a closed locale.’

There’s the rub. Rules are there to prevent overcrowding in popular parks, and those who adhere to them expect to be rewarded with a pristine environment and the assurance that others are playing by the rules, too.

In the end, only sanctions will make some people comply. On that river years ago, the rogue kayaker suffered no consequences and considered his infraction insignificant. A later violation on another continent cost him a fine, deportation and his job, impacts that made quite an impression indeed. Protecting outdoor spaces might not sway our decision-making, but a hefty fine and the threat of imprisonment might.