Listen to this essay

31 minute listen

Everything around you – from tables and trees to distant stars and the great diversity of animal and plant life – is built from a small set of elementary particles. According to established scientific theories, these particles fall into two basic and deeply distinct categories: bosons and fermions.

Bosons are sociable. They happily pile into the same quantum state, that is, the same combination of quantum properties such as energy level, like photons do when they form a laser. Fermions, by contrast, are the introverts of the particle world. They flat out refuse to share a quantum state with one another. This reclusive behaviour is what forces electrons to arrange themselves in layered atomic shells, ultimately giving rise to the structure of the periodic table and the rich chemistry it enables.

At least, that’s what we assumed. In recent years, evidence has been accumulating for a third class of particles called ‘anyons’. Their name, coined by the Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek, gestures playfully at their refusal to fit into the standard binary of bosons and fermions – for anyons, anything goes. If confirmed, anyons wouldn’t just add a new member to the particle zoo. They would constitute an entirely novel category – a new genus – that rewrites the rules for how particles move, interact, and combine. And those strange rules might one day engender new technologies.

Although none of the elementary particles that physicists have detected are anyons, it is possible to engineer environments that give rise to them and potentially harness their power. We now think that some anyons wind around one another, weaving paths that store information in a way that’s unusually hard to disturb. That makes them promising candidates for building quantum computers – machines that could revolutionise fields like drug discovery, materials science, and cryptography. Unlike today’s quantum systems that are easily disturbed, anyon-based designs may offer built-in protection and show real promise as building blocks for tomorrow’s computers.

Philosophically, however, there’s a wrinkle in the story. The theoretical foundations make it clear that anyons are possible only in two dimensions, yet we inhabit a three-dimensional world. That makes them seem, in a sense, like fictions. When scientists seek to explore the behaviours of complicated systems, they use what philosophers call ‘idealisations’, which can reveal underlying patterns by stripping away messy real-world details. But these idealisations may also mislead. If a scientific prediction depends entirely on simplification – if it vanishes the moment we take the idealisation away – that’s a warning sign that something has gone wrong in our analysis.

So, if anyons are possible only through two-dimensional idealisations, what kind of reality do they actually possess? Are they fundamental constituents of nature, emergent patterns, or something in between? Answering these questions means venturing into the quantum world, beyond the familiar classes of particles, climbing among the loops and holes of topology, detouring into the strange physics of two-dimensional flatland – and embracing the idea that apparently idealised fictions can reveal deeper truths.

Bosons and fermions differ from one another in various ways. But if we want to understand anyons, the characteristic that interests us goes by the name of ‘quantum statistics’, which concerns the rules of engagement that dictate how particles behave when grouped together and distributed in single-particle states. Experimentally speaking, only two kinds of quantum statistics have been found so far – one for fermions and one for bosons. And each is defined by what happens when two identical particles swap places.

To unpack what this means, let’s first consider a contrasting case. In classical physics, the state of the system is just the set of numbers for quantities like position and momentum that lets you predict how an object like a baseball will move next. Imagine a bucket of baseballs, then. You could label them Ball One, Ball Two, and so on. If Ball One is at the top of the bucket and Ball Two is at the bottom, that’s one distinct arrangement. If you swap them, you have created a new, physically different arrangement. In classical physics, these two different situations correspond to two different states, and you can distinguish between them by observing how Ball Two and Ball One exchanged locations. In fact, you can ‘tag’ every classical particle – every baseball in our example – and follow its motion along a path.

So far so good. But in quantum mechanics the story is different.

When you have a collection of particles, quantum mechanics doesn’t describe them one by one. It assigns a quantum state to the entire system, which can take the form of a field-like entity known as a ‘wavefunction’ that expresses the probabilities associated with various observable processes. It encodes, for instance, all possible energies, momenta, positions and, importantly, how the particles populate the available single-particle states. You might think about single-particle states as describing one particle’s possibilities, and the general state as describing all particles and their correlations.

What is it about quantum theory that entails two basic categories of particles?

Take a system of identical particles like electrons, where the state is represented by a wavefunction. What is the relationship between the state of the system and another new state where we swapped the locations of particles One and Two? Is it like the baseballs in our bucket?

Here’s the rub. In quantum mechanics, unlike in classical physics, there is no experiment that can be conducted, and no observation that we can make, that will allow us to distinguish between these two systems. We can’t ‘tag’ an electron and follow it along a path. Although quantum mechanics can represent these two situations differently, exchanging identical quantum particles can’t change anything that you measure experimentally or observe, so our theoretical description of states should respect this symmetry. This idea is known as ‘permutation invariance’.

Moreover, if permutation invariance implied that there are only two allowed behaviours of the quantum state when you swap identical particles, then there are only two kinds of quantum statistics – with only two corresponding classes of particles.

So, given a system of identical particles, what is it about quantum theory that entails two basic categories of particles?

The standard story is as follows. Represent the state with a wavefunction and examine how it changes when we swap two particles as with the baseballs. Permutation invariance implies that this system’s quantum state can be affected in only two ways. Either the swap leaves the wavefunction unchanged, giving us bosons, or it reverses its sign (from plus to minus or vice versa), producing fermions. Mathematically, this difference is tracked by a built-in multiplier – the plus or minus sign in our case – that records how the state responds to a particle swap. If this multiplier could take on different intermediate values, it would mean various particle classes, but the claim is that this marker can take only two forms. When you swap two identical bosons, the wavefunction appears exactly the same. It’s like tossing two identical baseballs into the air and catching them in opposite hands – nobody watching can tell anything changed. If you swap two fermion baseballs, however, the wavefunction picks up a minus sign.

But here’s the catch: that tidy textbook explanation rests on hidden assumptions. It assumes that swapping particles can only ever change the wavefunction by one simple kind of multiplier – plus or minus – and that swapping the same particles twice must always return you to the exact same state you started with. If you drop those assumptions, theoretically speaking, new possibilities open up. Now you can have other, more exotic kinds of particles – additional classes beyond bosons and fermions.

So far, we’ve seen that particle classes depend on quantum statistics – the rules governing particle behaviour and distribution. Those rules hinge on how the wavefunction changes when identical particles swap, tracked by a built-in multiplier. The textbook argument claims only two multipliers are possible (+1 for bosons and -1 for fermions), but that conclusion rests on unwarranted hidden assumptions.

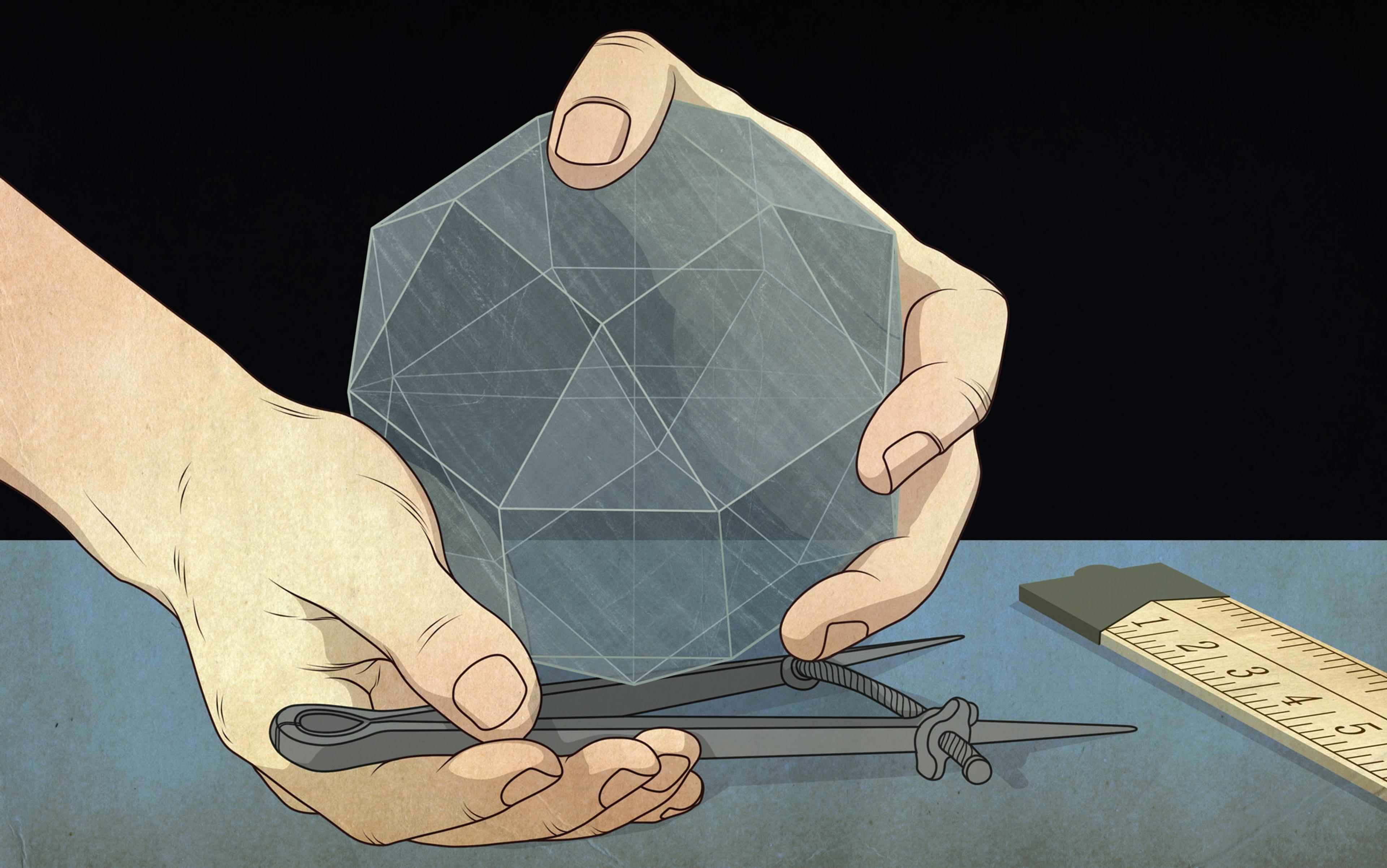

The key to understanding anyons lies in what happens, mathematically, when particles swap places – and how the space they move through shapes what’s possible. To see how this opens the door to new particle types, we need a framework that treats the indistinguishability of identical particles not as a problem to work around, but as a fundamental constraint on the space where they live.

One such framework, developed from the late 1960s, is called ‘the configuration space approach’. Here’s what it boils down to.

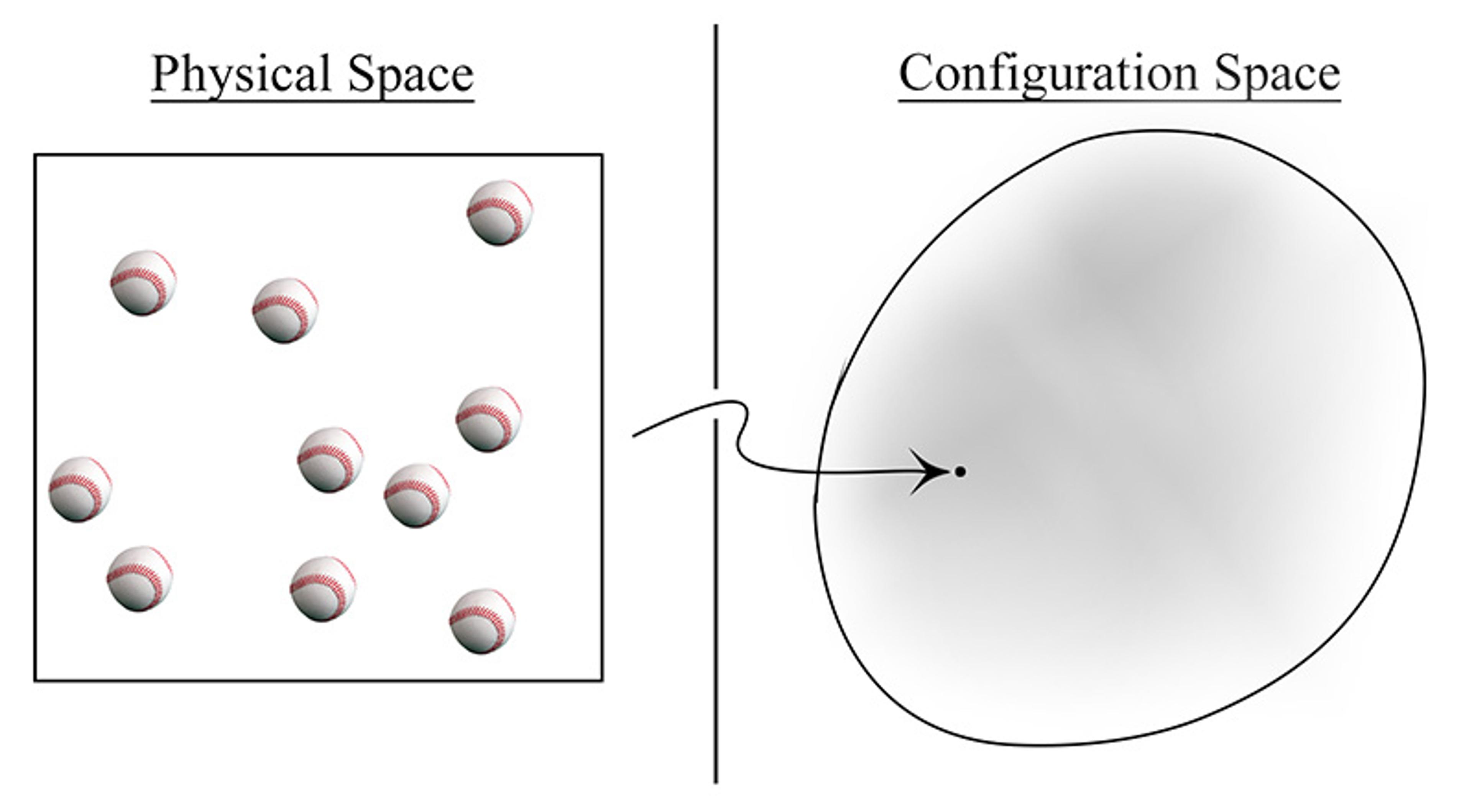

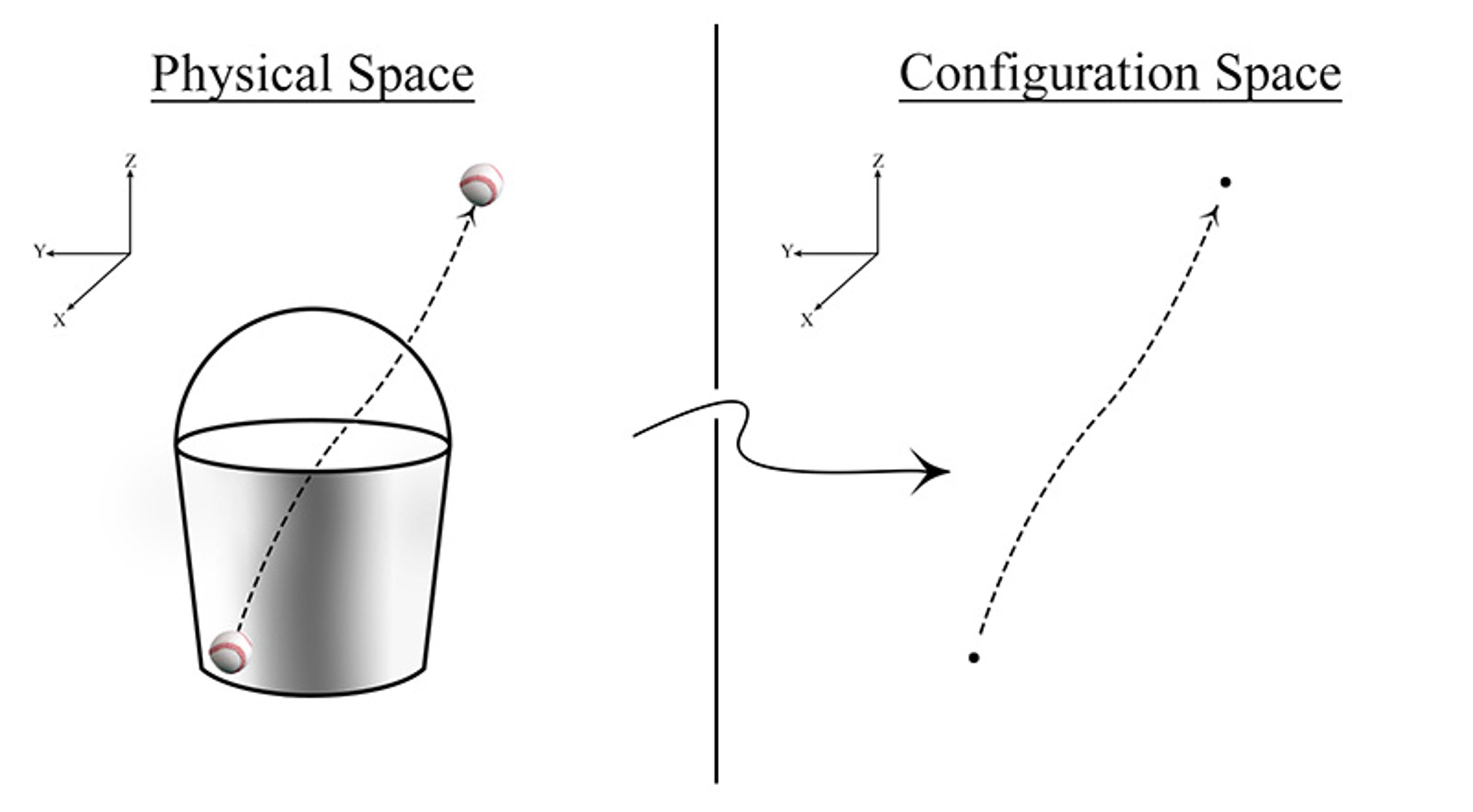

Configuration space is like a map, not of physical space, but where each point represents an arrangement of particles. Consider our bucket of baseballs. You could describe their position in three-dimensional physical space with coordinates on x, y, and z axes. For two baseballs, put each of their coordinates side by side and you have captured the arrangement. Add a third ball and you need more coordinates, and so on. Now imagine every possible arrangement (for whatever number of baseballs that you are interested in): that’s configuration space.

Paths through configuration space can signify how all of those particle positions change over time

As well as arrangements, physicists also think about ‘paths’ in this space. Here’s what that means.

Envision the configuration space of one particle to start. It will look just like a familiar three-dimensional space with the x, y, and z axes, since each point in configuration space represents a possible location that the particle may be in physical space.

Next, we can represent the trajectory of a particle over time, its path in physical space, as a path in configuration space. Now we generalise: if one point in configuration space represents the positions in space of many particles, then paths through configuration space can signify how all of those particle positions change over time – the trajectories of particles.

For identical particles, we tidy up the space in various ways to respect permutation invariance (the principle that swapping identical particles produces no observable difference). This includes ruling out coordinates where two particles sit exactly on top of each other. If we imagine classical objects like baseballs, it just doesn’t make any sense to say that two balls are in the same location. So, we cut those overlapping points out of configuration space – they form a kind of no-go zone, since they don’t correspond to any physical possibility. In effect, they leave ‘holes’ in the map. And it turns out that such holes are also needed in the more subtle case of quantum particles to allow the possibility of multiple particle types.

To understand what these holes mean, we need to take a brief detour into a branch of mathematics called topology. This may seem abstract, but it’s the key to seeing how anyons become possible, and how the structure of space itself can shape the categories of particle physics.

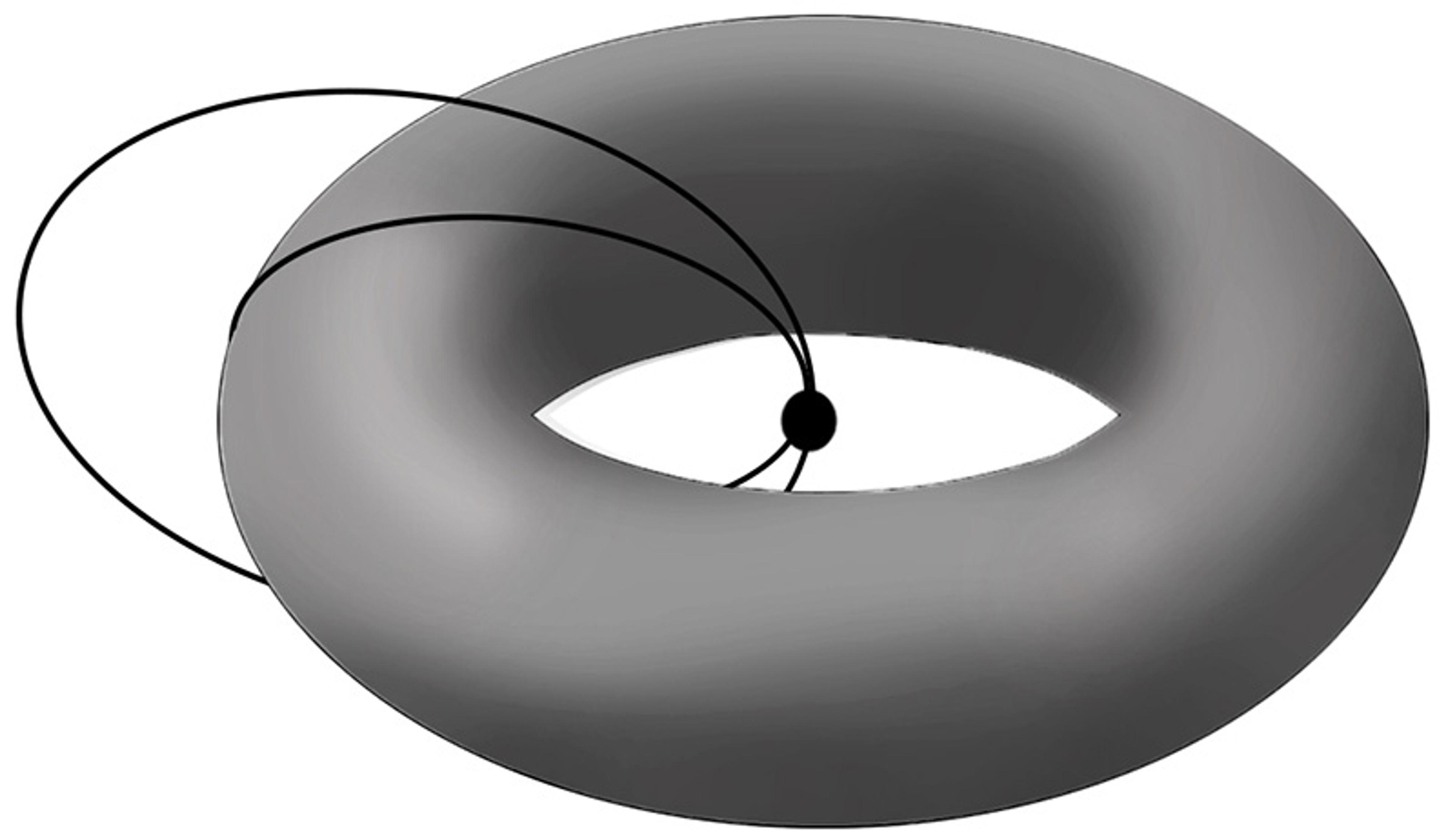

Topology is the study of what stays the same when you stretch or twist without tearing. A doughnut and a coffee cup are ‘the same’ topologically because each has one hole – a doughnut through the middle, a cup through the handle – and you can imagine morphing one into the other like soft clay.

No doubt this is a bit counterintuitive since a doughnut and a coffee cup, while complementing each other wonderfully, are not, in fact, the same. But topology has to do with properties that remain unchanged when you deform a shape without cutting or breaking. In that sense, doughnuts, coffee cups, bagels, lifebuoys, wedding rings, bracelets, scrunchies, etc, are topologically equivalent. And they are topologically different from a figure-eight pretzel (which is, in turn, the same as a triple-loop belt buckle or a three-handled mug).

Courtesy Wikipedia

Topologically speaking, there are different classes of spaces depending on the holes and loops involved

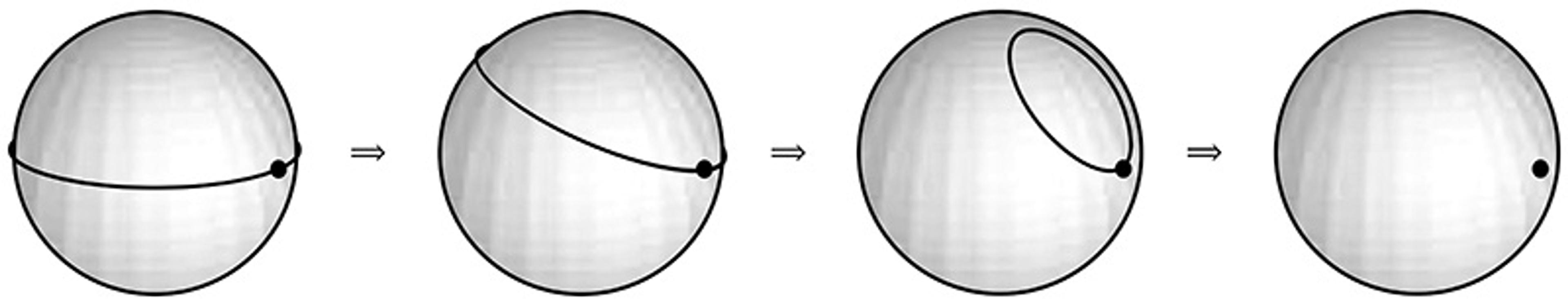

Loops – that is, closed paths – are a powerful way to detect holes, and they allow us to classify spaces in topology. If you can shrink down a loop to a point, and it doesn’t get stuck on a hole, then the space has no hole. Topologically speaking, it’s the simplest kind of space. The surface of a sphere is such an example.

If the loop gets caught, like a rubber band stuck around a donut, it reveals that a hole is there. From the perspective of topology, that’s a more complex, richer space.

Mathematicians sort loops and spaces into types. In a space with no holes, all loops are topologically the same, since they shrink away. But in a space with holes, there are genuinely different kinds of loops that can’t be undone. Topologically speaking, then, there are different classes of spaces depending on the holes and loops involved.

This is important to emphasise before continuing. The point of our detour into topology was to show that spaces with holes are topologically distinct – and that these differences can be used to classify spaces into different types. This is true of abstract mathematical spaces studied by a topologist, but it is also true of the configuration space of identical particles.

So, what does any of this have to do with quantum statistics and particle classes?

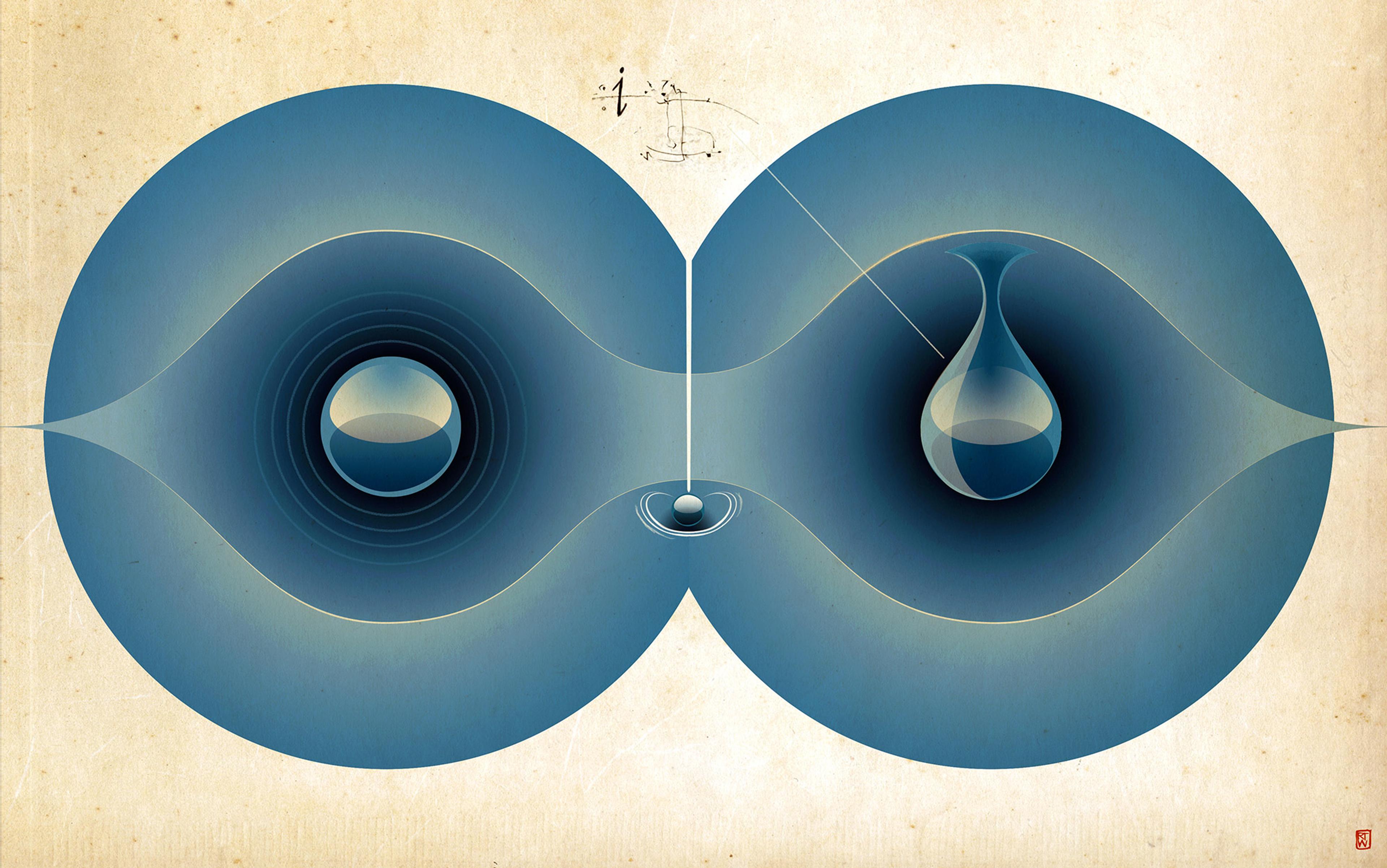

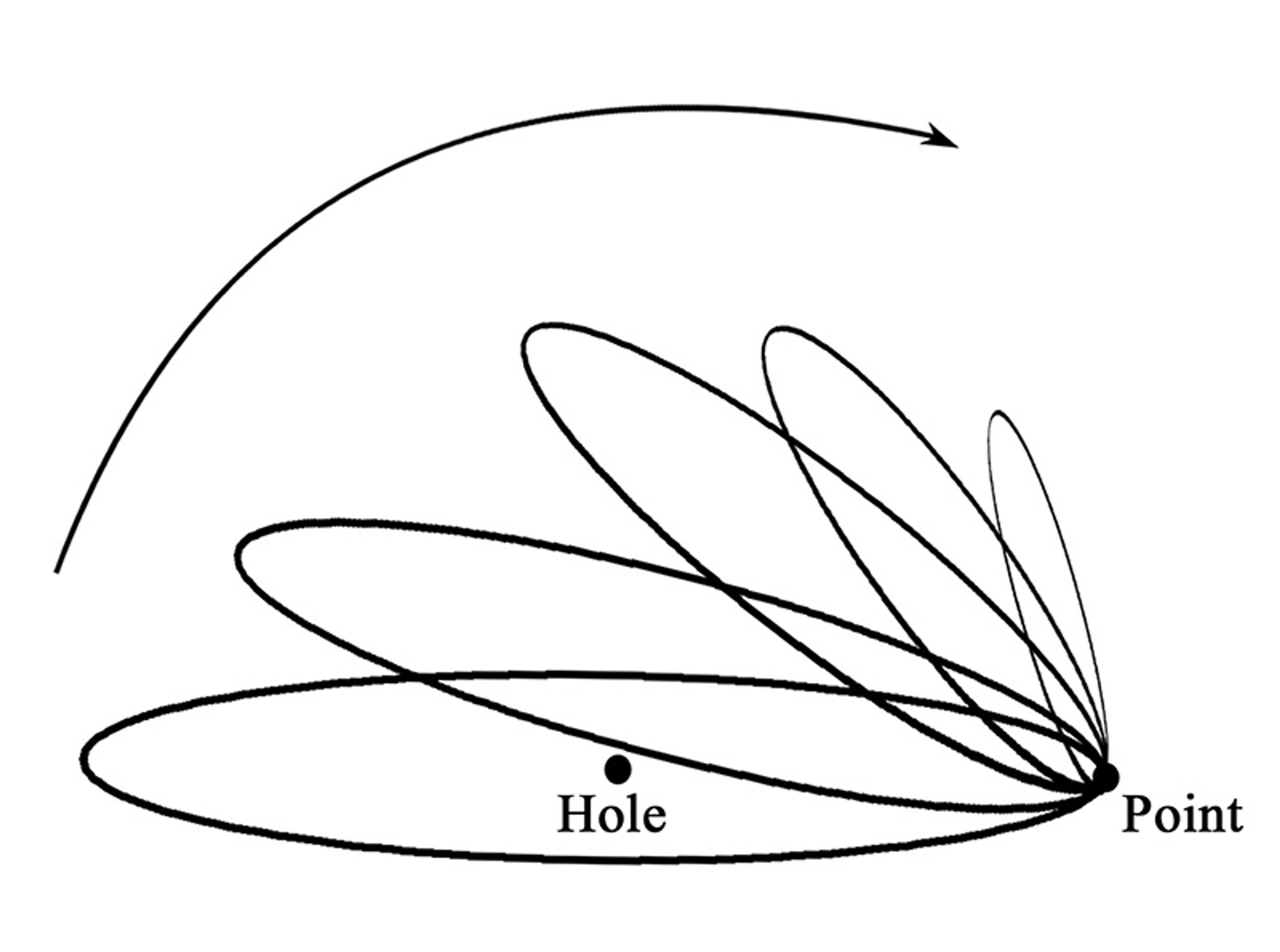

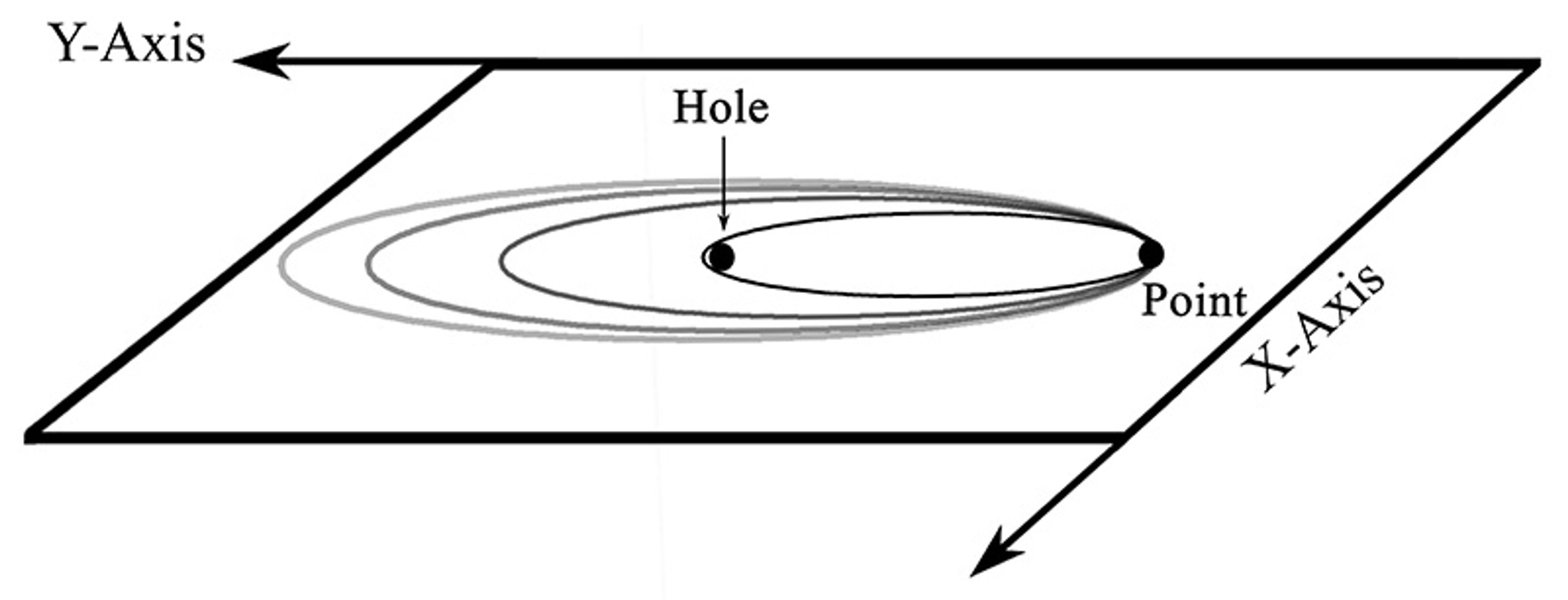

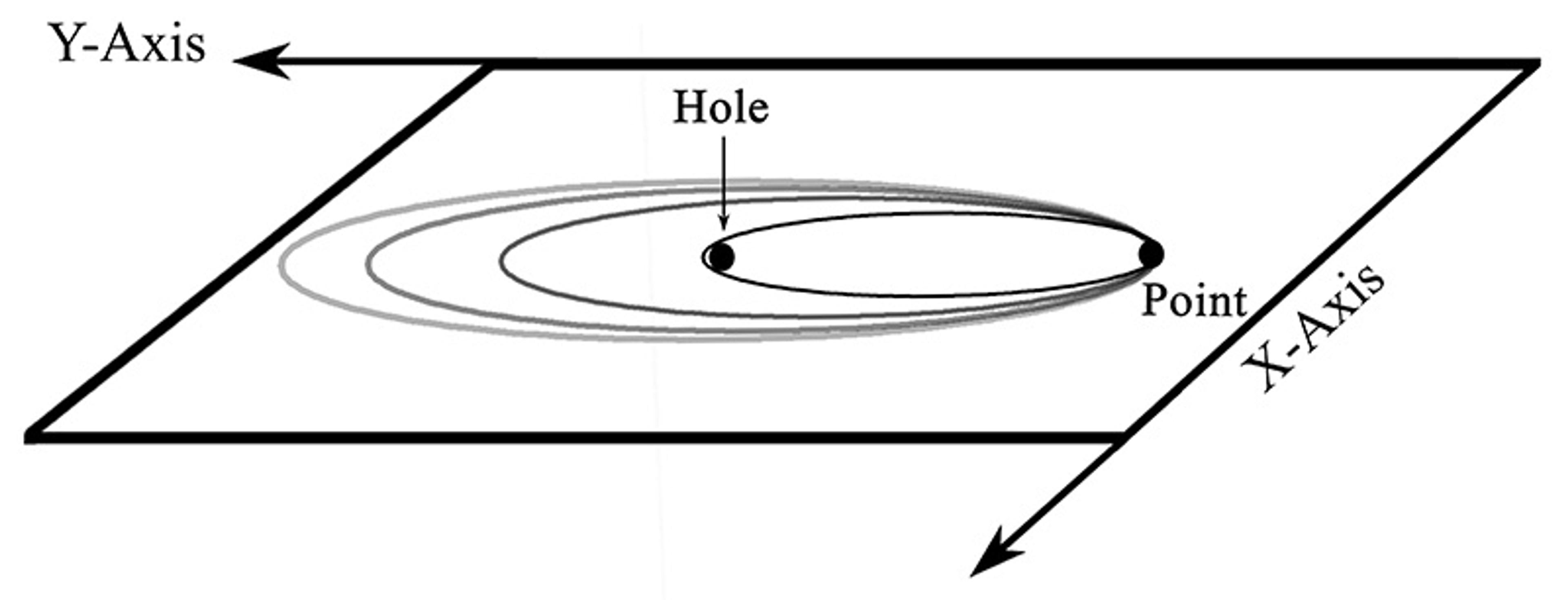

When we’re dealing with identical quantum particles, their configuration space – the abstract space of all possible arrangements – has holes. These holes represent the ‘no go’ zones. They affect how particles can move around one another. If you map out a path where two particles trade places, it forms a kind of loop in this space. Some of these loops can be undone, shrunk down until they disappear. Others get caught on the holes and can’t be undone. They represent configuration spaces with a richer topology.

One of the key insights of this approach – the configuration space approach to permutation invariance – is that quantum statistics are shaped by which loops the space allows: the way these paths are grouped determines what kinds of exchanges are possible and, in turn, what kinds of quantum statistics the particles can have. In other words, the topology of configuration space determines quantum statistics with the corresponding particle type.

The configuration space – the holes and loops – constrains how quantum states change when particles are swapped

Loops, then, are playing two roles at once. From a topological point of view, they help us classify spaces into ones that are topologically simple and ones that are more complex. From the perspectives of physics, when the space in question is the configuration space of identical particles, loops can correspond to particle exchanges (having to do with quantum statistics and particle class). So, a richer topology in configuration space, with more kinds of non-shrinkable loops, corresponds to more distinct ways particles can be swapped. And that is precisely what opens the door to different forms of quantum statistics and new particle kinds.

Let’s briefly take stock. Particle class – that is, bosons, fermions or something more exotic – goes hand in hand with quantum statistics – the rules governing how such particles interact and occupy single-particle states – which depends on how the system’s quantum state, or wavefunction, changes when identical particles swap. That is, on the built-in marker that it picks up when particles are exchanged. Permutation invariance is the principle that swapping identical quantum particles makes no observable difference, so the theory must treat those exchanged states as equivalent in some sense. What the configuration-space approach does is build permutation invariance straight into the space that describes all possible arrangements of particles and their trajectories. In doing so, the topological shape of the configuration space itself – the holes and permitted loops – constrains how quantum states may change when particles are swapped. And this establishes those same rules that concern quantum statistics and particle kind.

But, as we’ll see next, thinking in two dimensions – the world of anyons – changes everything.

According to the configuration-space approach, quantum statistics are determined by the topology of configuration space. A richer topology means more possibilities for statistics and, correspondingly, particle type. So, what happens mathematically when we swap particles?

Just like we explored earlier, this approach says that if you swap identical particles in three dimensions, the built-in multiplier that the wavefunction picks up is either a plus or a minus sign. The topology of configuration space is rich enough to give you two kinds of quantum statistics: one for bosons and one for fermions. But things get more interesting when you move to two dimensions because, topologically speaking, configuration space in two dimensions is richer.

This might seem counterintuitive, so here’s a way to see this.

In two dimensions, loops can get caught around holes: we are dealing with a space that is topologically richer

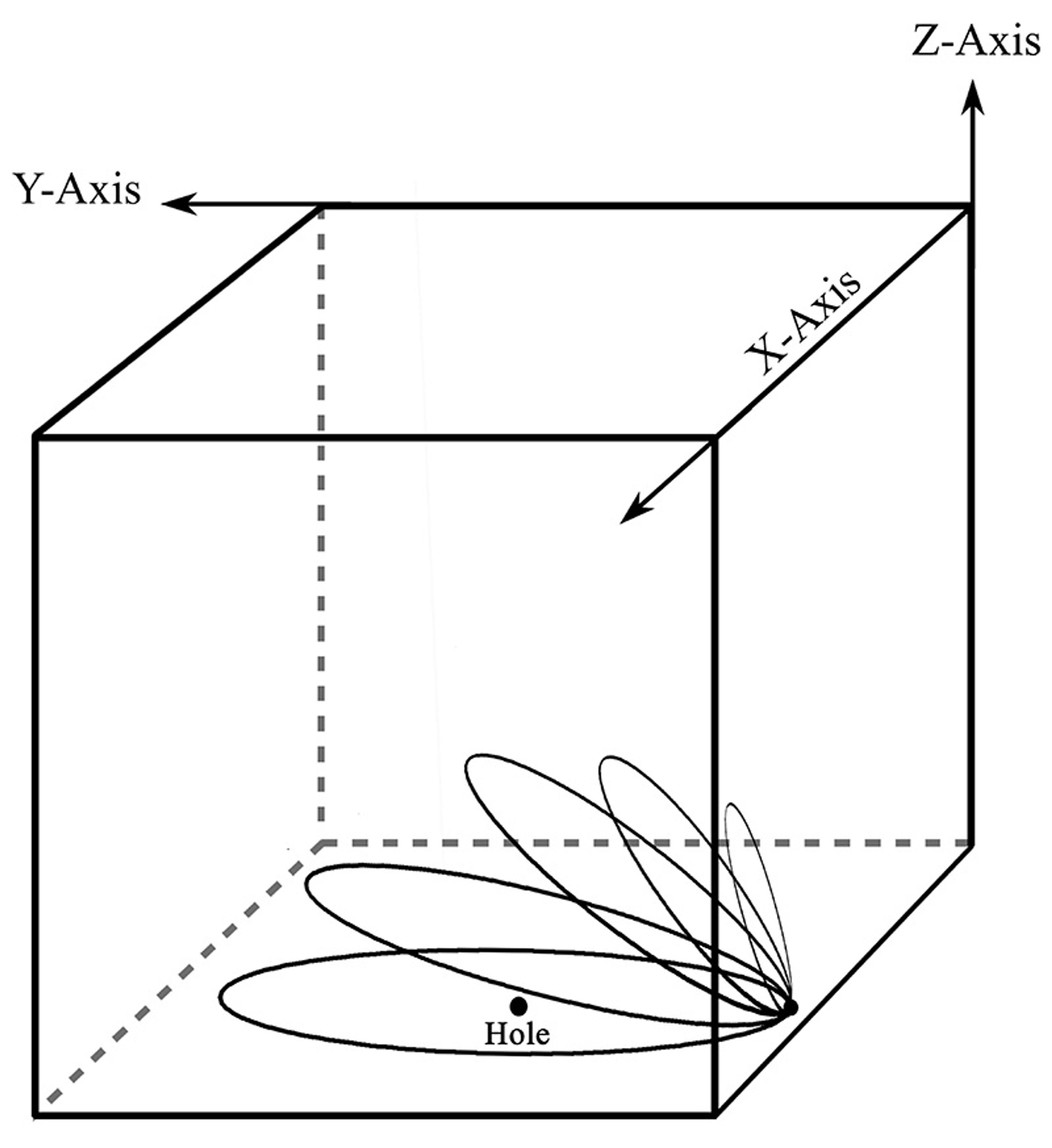

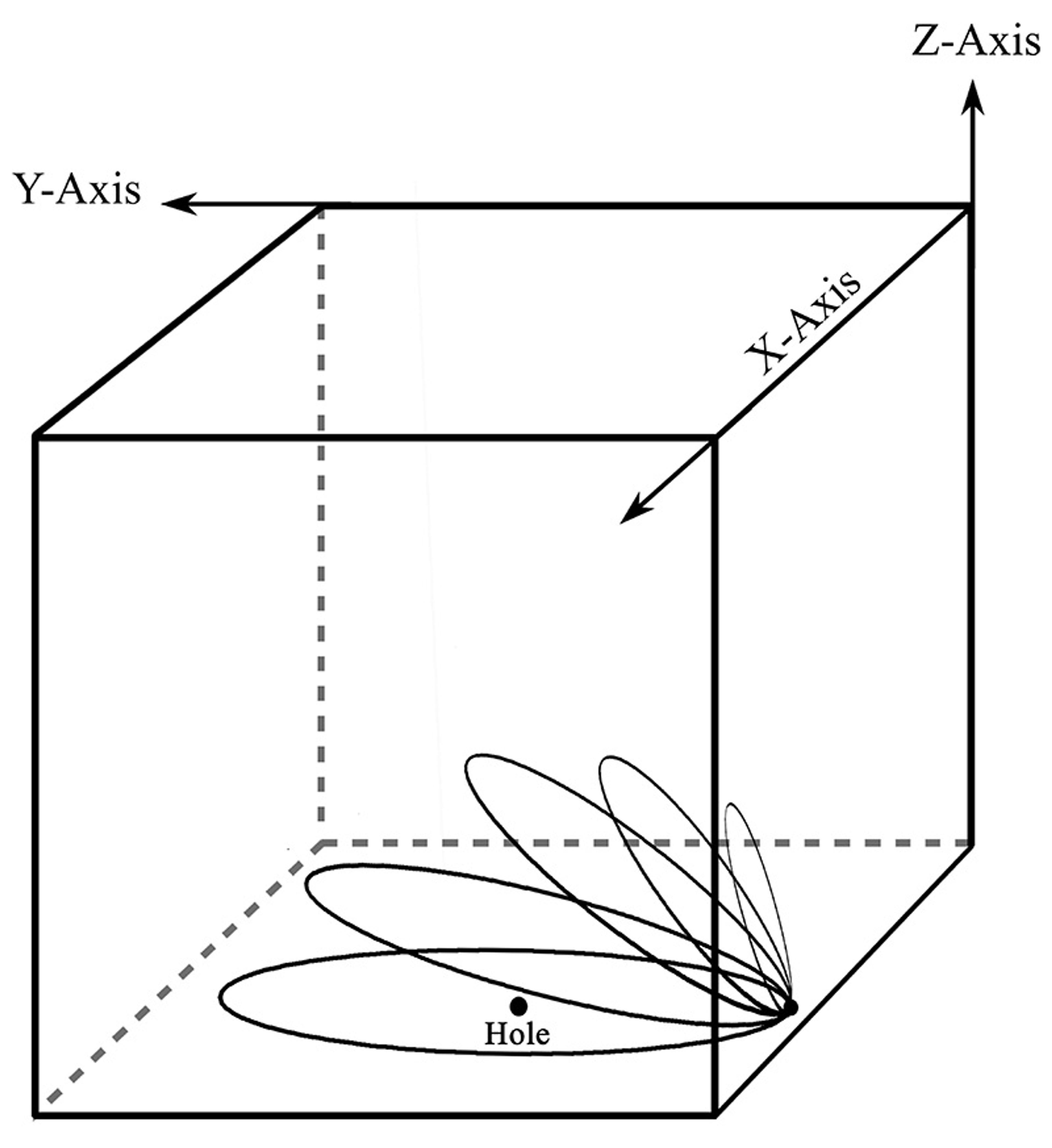

Recall that we can classify topological spaces according to which loop can be shrunk to a point without getting stuck. Imagine a cube with a hole in it (as our candidate space of interest). In three dimensions, you can always slip off the loop into the third dimension and make it vanish.

Flatten the world and the story changes. In two dimensions, loops can get caught around holes, which means that we are dealing with a space that is topologically richer. We’ve moved from a space that is simple, where all loops can be shrunk to a point (despite the hole), to one that is more complex.

And this is where anyons enter the story.

In a flat world, the built-in multiplier that marks an exchange isn’t stuck with only two settings – plus or minus – it can take on intermediate values. These intermediate values signify novel rules for particle behaviour and distribution, that is, different quantum statistics. In two dimensions, the way in which particles wind around one another can tune that multiplier – sometimes just by how much and which way they wind, and in some systems even by order of moves, leaving a ‘memory’ of how the motion unfolded. When that happens, the system’s description after an exchange isn’t boson-like or fermion-like – it’s something new: anyons.

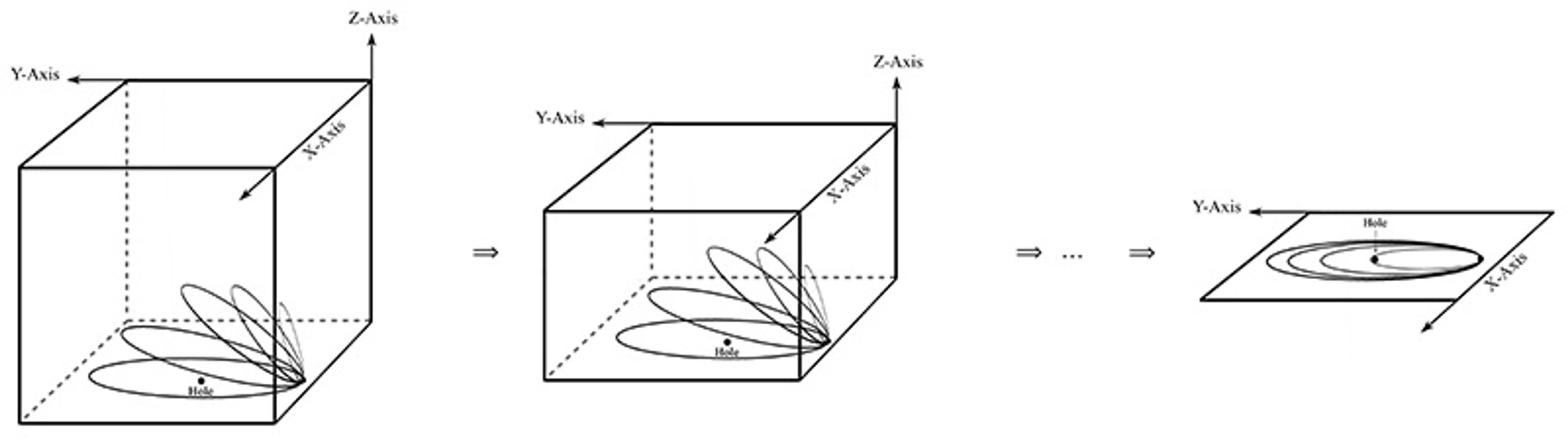

We’ve now seen how anyons can emerge in theory, but theory alone isn’t reality. Our world is three dimensional, which means two-dimensional configuration spaces are idealisations of sorts. Changing the analogy from baseballs to the flat game of pool, it’s like pretending billiard balls can only ever roll across the table, even though we know a ball can always pop up off the surface.

This raises the question: anyons live in flatland, in a simplified, two-dimensional world. Can they survive in the full three dimensions of reality? Despite all the experimental buzz and theoretical interest, there are reasons to worry that anyons might not be real after all.

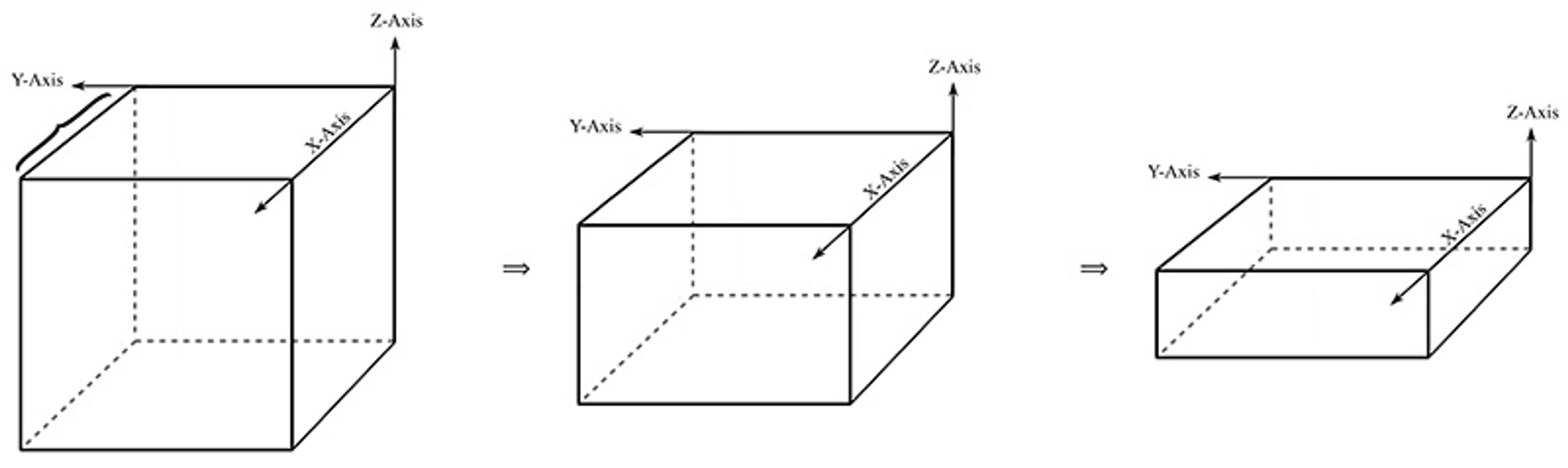

To see why, imagine relaxing the idealisation just a little. Think of a series of three-dimensional boxes, each one flatter than the last. The width and length stay the same, but the height gradually shrinks – getting closer and closer to a flat, two-dimensional sheet. That’s our candidate anyon setup:

Put a forbidden spot in the middle to stand for the places identical particles aren’t allowed to occupy; in our picture, that acts like a hole in configuration space:

As you squash down the box to zero height, you get a perfectly flat square. Now, walk a loop around the hole. In flatland, that loop can’t be shrunk down to a point, it gets stuck on the hole. This points to a configuration space of identical particles that is topologically rich enough to support anyons.

But add just a sliver of third dimension, and everything changes. Now you can lift up the loop and shrink it down. This means that, despite the hole, the topology of the space is too simple for anyons. The difference between two and three dimensions isn’t gradual; it’s all or nothing. Either you’re flat enough for anyons to exist, or you’re not. There’s no in between.

That’s the warning sign. As soon as we add even a little depth, the structure that makes anyons possible disappears. We seem to be left, then, with three choices.

Perhaps there’s another way to explain them that doesn’t rely so heavily on the quirks of idealised, flat spaces

First, maybe anyons aren’t real in a deep sense. For instance, some philosophers have argued that so-called ‘paraparticles’ – a whole other class of particles – are really nothing more than bosons and fermions in disguise. By the same reasoning, one could argue that anyons are simply familiar particles dressed up with extra labels. The difference lies in the notation, not in the physics. Mathematically, for the simpler cases, that might be enough. But in the more complex cases, in which particle paths wind around each other leaving a lasting memory on the system, it’s much harder to dismiss the new behaviour as mere convention.

Alternatively, then, maybe we need a new framework that captures the strange behaviour without relying on a structure that evaporates the instant we lift into the third dimension. If experiments definitively confirm the existence of anyons, perhaps there’s another way to explain them that doesn’t rely so heavily on the topological quirks of idealised, flat spaces.

Or maybe there’s a third possibility, one that flips the script.

Perhaps some real systems make the idealisation come true by locking motion strictly into two dimensions. Think ultra-thin, engineered layers where particles are confined so tightly that moving out of plane isn’t just unlikely, it’s physically off limits. In that case, we’re not merely idealising; we’re building genuine flatlands in the lab. The particles don’t just behave as if they live in a two-dimensional world – they actually do. And when that happens, fiction becomes fact.

In 1982, physicists studying ultra-thin materials made a surprising discovery. Under strong magnetic fields and extreme cold, electrons in these materials stopped behaving like individual particles and started acting in unison, forming strange states that seemed to carry only a fraction of an electron’s charge. This was the fractional quantum Hall effect, a phenomenon so unexpected and puzzling that it earned Daniel Tsui, Horst Störmer and Robert Laughlin the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1998. To make sense of it, researchers proposed that the ripples of charge in these flat, layered materials might be behaving like anyons. That idea stuck, and flat, ultra-thin systems became the natural hunting ground. Over time, hints of anyon-like behaviour showed up in other exotic materials too, like quantum spin liquids.

So, if anyons exist, what kind of existence is it? None of the elementary particles are anyons. Instead, physicists appeal to the notion of ‘quasiparticles’, in which large numbers of electrons or atoms interact in complex ways and behave, collectively, like a simpler object you can track with novel behaviours.

Picture fans doing ‘the wave’ in a stadium. The wave travels around the arena as if it’s a single thing, even though it’s really just people standing and sitting in sequence. In a solid, the coordinated motion of many particles can act the same way – forming a ripple or disturbance that moves as if it were its own particle. Sometimes, the disturbance centres on an individual particle, like an electron trying to move through a material. As it bumps into nearby atoms and other electrons, they push back, creating a kind of ‘cloud’ around it. The electron plus its cloud behave like a single, heavier, slower particle with new properties. That whole package is also treated as a quasiparticle.

Some quasiparticles behave like bosons or fermions. But for others, when two of them trade places, the system’s quantum state picks up a built-in marker that isn’t limited to the two familiar settings. It can take on intermediate values, which means novel quantum statistics. If the theories describing these systems are right, then the quasiparticles in question aren’t just behaving oddly, they are anyons: the third type of particles.

Anyons don’t appear in the most fundamental theories, but they show up in thin, flat systems

In other words, while none of the elementary particles that physicists have detected are anyons – physicists have never ‘seen’ an anyon in isolation – we can engineer environments that give rise to emergent quasiparticles portraying the quantum statistics of anyons. In this sense, anyons have been experimentally confirmed. But there are different kinds of anyons, and there is still active work being done on the more exotic anyons that we hope to harness for quantum computers.

But even so, are quasiparticles, like anyons, really real? That depends. Some philosophers argue that existence depends on scale. Zoom in close enough, and it makes little sense to talk about tables or trees – those objects show up only at the human scale. In the same way, some particles exist only in certain settings. Anyons don’t appear in the most fundamental theories, but they show up in thin, flat systems where they are the stable patterns that help explain real, measurable effects. From this point of view, they’re as real as anything else we use to explain the world.

Others take a more radical stance. They argue that quasiparticles, fields and even elementary particles aren’t truly real: they’re just useful labels. What really exists is not stuff but structure: relations and patterns. So ‘anyons’ are one way we track the relevant structure when a system is effectively two-dimensional.

Questions about reality take us deep into philosophy, but they also open the door to a broader enquiry: what does the story of anyons reveal about the role of idealisations and fictions in science? Why bother playing in flatland at all?

Often, idealisations are seen as nothing more than shortcuts. They strip away details to make the mathematics manageable, or serve as teaching tools to highlight the essentials, but they aren’t thought to play a substantive role in science. On this view, they’re conveniences, not engines of discovery.

But the story of anyons shows that idealisations can do far more. They open up new possibilities, sharpen our understanding of theory, clarify what a phenomenon is supposed to be in the first place, and sometimes even point the way to new science and engineering.

The first payoff is possibility: idealisation lets us explore a theory’s ‘what ifs’, the range of behaviours it allows even if the world doesn’t exactly realise them. When we move to two dimensions, quantum mechanics suddenly permits a new kind of particle choreography. Not just a simple swap, but wind-and-weave novel rules for how particles can combine and interact. Thinking in this strictly two-dimensional setting is not a parlour trick. It’s a way to see what the theory itself makes possible.

The flat setting reveals what would count as a genuine signature, and what would be a mere lookalike

That same detour through flatland also assists us in understanding the theory better. Idealised cases turn up the contrast knobs. In three dimensions, particle exchanges blur into just two familiar options of bosons and fermions. In two dimensions, the picture sharpens. By simplifying the world, the idealisation makes the theory’s structure visible to the naked eye.

Idealisation also helps us pin down what a phenomenon really is. It separates difference-makers from distractions. In the anyon case, the flat setting reveals what would count as a genuine signature, say, a lasting memory of the winding of particles, and what would be a mere lookalike that ordinary bosons or fermions could mimic. It also highlights contrasts with other theoretical possibilities: paraparticles, for example, don’t depend on a two-dimensional world, but anyons seem to. That contrast helps identify what belongs to the essence of anyons and what does not. When we return to real materials, we know what to look for and what to ignore.

Finally, idealisations don’t just help us read a theory – they help write the next one. If experiments keep turning up signatures that seem to exist only in flatland, then what began as an idealisation becomes a compass for discovery. A future theory must build that behaviour into its structure as a genuine, non-idealised possibility. Sometimes, that means showing how real materials effectively enforce the ideal constraint, such as true two-dimensionality. Other times, it means uncovering a new mechanism that reproduces the same exchange behaviour without the fragile assumptions of perfect flatness. In both cases, idealisation serves as a guide for theory-building. It tells us which features must survive, which can bend, and where to look for the next, more general theory.

So, when we venture into flatland to study anyons, we’re not just simplifying – we’re exploring the boundaries where mathematics, matter and reality meet. The journey from fiction to fact may be strange, but it’s also how science moves forward.