Leonard Cohen’s autumnal years have been afflicted, and his writing nuanced, by more than a simple awareness of his own mortality. The Canadian singer-songwriter spent most of the 1990s in a Zen monastery in California, during which time his manager (and former lover) Kelley Lynch siphoned off several million dollars’ worth of earnings, mostly from the sale of his publishing company to Sony. Not being particularly astute in such matters, it took Cohen several years to work out what had happened, by which time he was facing a severely diminished bank account and a rather larger tax bill.

The resulting legal squabbles no doubt sapped Cohen’s creative powers, and used up even more of his diminished funds. That Lynch was ordered to pay him back was little consolation — she hasn’t done so, and is now in prison for harassing him. Yet Cohen was able to cast a ruefully theological spin on events and all the time he was forced to spend in other people’s offices. As he put it to one Canadian journalist in 2009: ‘If God wants to bore you to death, I guess that’s His business.’ Such, we might think, is the wisdom of Cohen. His music has always awakened impulses in his devotees to see him as some sort of mentor for the melancholic. But this impulse took a new twist once Cohen’s own fortunes looked bleak: what would, or could, he do in the face of this personal crisis?

The reality, of course, was that Cohen needed to find some cash. His output had never been prolific (he has released a dozen studio albums in a 45-year recording career) and, in any case, his critical acclaim has never been matched in sales figures. Where he had always been able to turn a respectable profit was through live shows, though he hadn’t toured since the early 1990s. Through necessity rather than any particular inclination, Cohen went back on the road.

What he craved in his association with Roshi was something he called ‘the voluptuousness of austerity’

But 2008 was a tumultuous time in the wider world. As Cohen and his band snaked through North America, Europe and Australasia, the full impact of the global economic meltdown was beginning to take hold. But this was not some preening rock behemoth making a brief stopover from tax exile in Monaco or the Bahamas. Cohen was just another shlimazel who’d woken up one morning to find his pension pot had been cleaned out. Many of those who came to see him perform were facing all too similar anxieties. Long-term fans were perhaps contemplating reduced retirements; the more recent ‘converts’, many of them encouraged by the recommendations of Nick Cave or Rufus Wainwright, were similarly fearful of their diminished futures, their faith in the material rewards of modern capitalism deflated. It was a potential congregation of gloom and despondency, almost a parody of Cohen’s reputation as the patron saint of bedsit depressives. What philosophical (or, if so inclined, spiritual) consolation could Cohen offer? The fact that his singing voice, never the most technically perfect instrument, was now little more than a forlorn croak simply added to the mood. The line, ‘I was born with the gift of a golden voice’ (from ‘Tower of Song’, on the 1988 album I’m Your Man) was greeted every night with an ironic cheer.

Cohen’s religious background is one of contradiction and complexity. Born into a Jewish family in Montreal in 1934, his maternal grandfather was a rabbi, and the young Leonard enjoyed reading the Book of Isaiah with him. Unsurprisingly, Old Testament imagery crops up regularly in his poems and songs, adding to his reputation — only partly deserved — for austerity and solemnity. Yet Montreal was very much a Catholic city (Cohen even had an Irish nanny as a child), and his work is just as likely to refer to Jesus, Mary or Joan of Arc. Indeed, his first successful song, ‘Suzanne’, tells of ‘our lady of the harbour’, a statue that stands in the chapel of Nôtre Dame de Bon Secours, one of the city’s oldest churches.

But while the imagery might have appealed, Cohen never thought of converting to Catholicism. In his own idiosyncratic way, he maintained a loyalty to Judaism, despite his many indulgences in the archetypal rock and roll foibles of sex and drugs. It wasn’t until the age of 33, by which time he had begun to make his name as a poet and novelist and was recording his first album, that he became seriously interested in the doctrine and practice of another religion — Zen Buddhism.

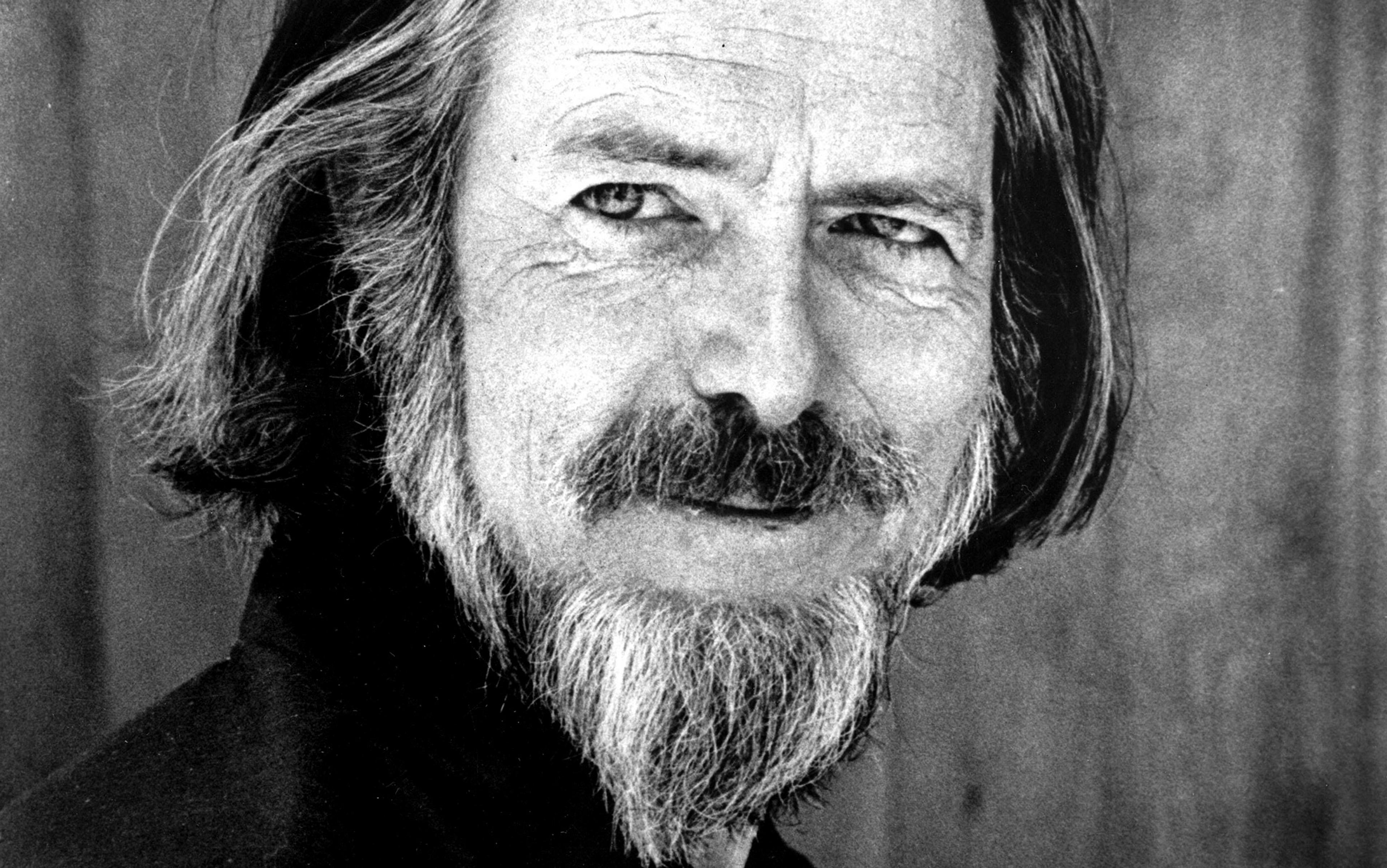

Laughing Lenny: ‘all the perfect and broken hallelujahs have equal value’. Photo by Bob King/Corbis

Though he became closely associated with the teachings of the Rinzai monk Joshu Sasaki, known as Roshi, Cohen still identified himself as a Jew. What he craved in his association with Roshi was something he called ‘the voluptuousness of austerity’, a delectably contradictory concept that echoes both the koan (the paradoxical statements and questions that are central to Zen practice) and Cohen’s own attitude to the spiritual life: at various times committed, ambivalent or mocking, and sometimes all three at once. One of the things that attracted Cohen to Roshi’s teachings was the teacher’s ability to discuss the benefits of self-denial while knocking back cups of sake. The two of them also later bonded over a shared fondness for brandy. When Cohen became a resident at Roshi’s monastery on Mount Baldy in California, he would wake up half an hour before the 3am start demanded of residents, not for extra meditation time, but because he knew he’d need vast quantities of coffee and cigarettes to prepare himself for the drudgery of the prescribed rituals.

There is, understandably, a temptation to look for a doctrine or creed in Cohen’s writing that captures his spiritual outlook — nonetheless, it is a temptation that is not easily satisfied. The history of his best-known song, ‘Hallelujah’ (originally released on the Various Positions album in 1984), neatly encapsulates his spiritual eclecticism. Its lyrics draw on the story of David and Bathsheba in the second Book of Samuel, but Cohen so obsessively wrote and rewrote the piece over the years that the explicitly theological content (‘Maybe there’s a God above…’) came and went. What remains, above all, is a tribute to the power of religious music, of hymns and ritual itself, without specific acknowledgement of any particular religious truth underpinning it. There is something indefinably hymn-like about it — Guy Garvey of the band Elbow, who comes from a Catholic background, has described it as ‘a mantra’ — but ultimately it transcends any particular denominational categorisation, and has found favour with the devout and atheists alike, as well as most steps in between.

His recent temporal crisis might have, in a very literal sense, been about being broke but, in spiritual terms, Cohen has always been broken

If anything, it’s a hymn to hymns, rather than to God (or gods). As such, it’s been recorded by the Algerian singer Khalida Azzouza and by the erstwhile Songs of Praise host Aled Jones, but it is also played every Saturday night on the radio station of the Israeli Defence Forces. (Cohen played some ad hoc concerts for Israeli soldiers during the Yom Kippur war in 1973.) Cohen tends to be evasive when asked to explain his work, but he suggests that the lyrics explain that ‘Many kinds of hallelujahs do exist, and all the perfect and broken hallelujahs have equal value.’ This notion of brokenness, an awareness of one’s own frailties and imperfections, crops up time and again in Cohen’s lyrics. In ‘Anthem’ (1992), the notion of the ‘perfect offering’ (the Biblically sanctioned sacrifice to God) is spurned in favour of the ‘crack in everything — that’s how the light gets in.’ Nothing good (or enlightening) is possible without flaws or fractures. In ‘Come Healing’, from his most recent album Old Ideas (2012), brokenness is specifically equated with the splinters of Christ’s cross. What is paramount is Cohen’s awareness of the grimness of existence, and for many years critics sarcastically dubbed him ‘Laughing Lenny’ for the apparently gloomy nature of his outlook. But, it is from such fractures and splinters that the ‘healing of the spirit’ comes. His recent temporal crisis might have, in a very literal sense, been about being broke but, in spiritual terms, Cohen has always been broken. Brokenness is not an end in itself, but an opportunity to allow something else to happen.

While Cohen has frequently dealt with religious themes in other songs, the more often he does it, the harder it is to pin down to any specific ideology. ‘Who By Fire’ (1974) is based on the structure of the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead; ‘The Smokey Life’ (1979) suggests the impermanence at the core of Buddhism; ‘Anthem’, with its bells and ‘holy dove’ hints at the Christian ritual and imagery that informed much of his early works. But Cohen’s theology, however he might define it, seems anything but easy-going. Old Ideas is riddled with intimations of mortality. As well as ‘Come Healing’, it includes a piece simply titled ‘Amen’ that sounds almost like a crib sheet for the King James Bible, with references to angels, ‘the blood of the lamb’, and the assertion that ‘vengeance belongs to the lord’.

Some fans might regard themselves more as disciples than mere enthusiasts. Yet, while Cohen might have admired the rigours of discipline — as a boy he’d seriously contemplated joining the Canadian army, and one of the attractions of his time in the Buddhist monastery was the quasi-military discipline it imposed — he was always wary of those who sought to administer it. He might have had a close and fond relationship with Roshi the Zen master, but he never saw him as a guru. As Cohen said in an interview on Mount Baldy: ‘I’ve always had a great suspicion of charismatic holy men… A lot of them are just head hunters.’ It was a resistance to being led that he’d expressed as far back as his first album, Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967). The lyrics of ‘Master Song’ from that album castigate the chancers and charlatans that he — in common with many of his contemporaries — had encountered in the quest for spiritual fulfilment. True to his Jewish upbringing, Judaism, Cohen lacks any particular evangelical urge or thirst for converts.

At a Cohen concert, it is possible to be in the company of tens of thousands of fellow fans, and yet still feel exquisitely alone

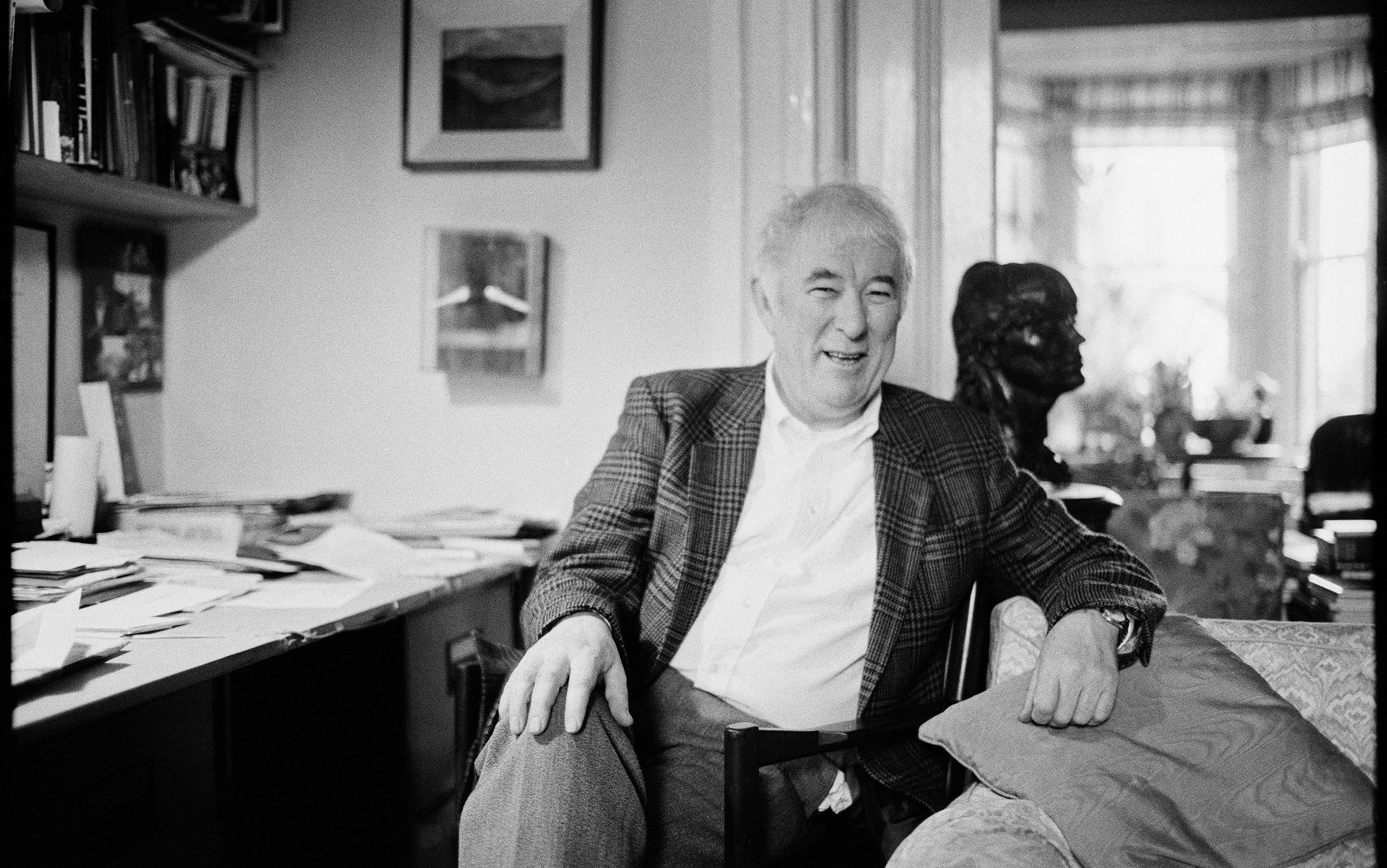

Cohen himself certainly isn’t claiming to be any kind of leader, spiritual or otherwise. The rabbinical line had stopped with his grandfather. And yet, many of those who have been to one of Cohen’s concerts report some kind of spiritual response, something beyond the purely earthbound sensation of going to a good gig. Perhaps the closest analogy is with the waiting worship of a traditional Quaker meeting, which operates without leadership or liturgy; in this analogy, Cohen himself is more of a ‘facilitator’, whose songs awaken something individual rather than collective. At a Cohen concert, it is possible to be in the company of tens of thousands of fellow fans, and yet still feel exquisitely alone. In that context, the sober grey suit and fedora he has adopted as his stage outfit make him look more like an undertaker than a priest.

If Cohen does have any particular spiritual message — and I rather suspect he’ll go to his grave denying such a thing — it is this call to the individual. Other rock performers — Dylan the Christian, Cat Stevens/Yusuf Islam the Muslim, George Harrison the devotee of Hare Krishna — have evangelised for their chosen faiths, but that’s too easy a liturgy for Laughing Lenny, who has never promoted Judaism or Zen or any other particular creed as a panacea. He has crafted his own method of coming to terms with the transcendent, but doesn’t offer it as an off-the-peg gift to the punters. If there is such a thing as Cohenism, it is simultaneously syncretic and idiosyncratic. It’s for Cohen alone: the fans have to find their own paths. ‘You don’t need to follow me,’ he seems to intone along with Monty Python’s Brian. ‘You don’t need to follow anybody.’ Each of us has to compose a personal amen, a high and lonesome — and defiantly imperfect — hallelujah.

Leonard Cohen passed away in November 2016. His last albums are ‘You Want It Darker’ (2016) and ‘Thanks for the Dance’, released posthumously in 2019.