When I was a child, my parents would receive packages from home. These were fat cardboard boxes lacquered in tape. They didn’t come directly from home – from Sierra Leone, that is – but from some friend or relative who had gone home for a couple weeks and was kind enough to collect requested items and stow them away in their luggage.

Ar say, you go bring me…?

No worry. Ar go bring am.

Once in the States, they’d reassemble them into packages and ship them to my parents and anyone else awaiting some goods. The recipients, in turn, were expected to do the same whenever they went home. Collect, store, and ship: this was one of the unspoken rules of our diaspora.

These packages contained stuff – things you take for granted when they’re easily accessible to you, but gain new significance when they’re no longer within reach. This includes black soap, smoked fish, Krio primers, religious paraphernalia, kanya snacks…

And cassettes, CDs – there was always music. The music would cut across different genres; from calypso to milo jazz, highlife to hymns, palm-wine music to goombay. Most of the artists were Sierra Leonean – Ebenezer Calendar, Salia Koroma, Dr Oloh and His Milo Jazz Band, Blind Musical Flames, Freetown’s Leading Sextet, and Afro National, for instance. But a few came from other African countries, like Kanda Bongo Man from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and even some from the Caribbean, like Lord Kitchener from Trinidad and Tobago, and Lloyd Lovindeer from Jamaica. (For the longest time, I assumed Lovindeer was a Sierra Leonean. I couldn’t imagine him as otherwise).

Whenever we received new music, my parents would play it for weeks on end. On reflection, it seemed to deepen their association with home. For one thing, it gave them a sense of continuity. They could keep abreast of the social, political, musical and linguistic developments that occurred since they’d left. They could consider the latest influences on Freetown, Bo and other places of personal importance. And, if they so chose – which I’m not sure if they did or didn’t – they could even imagine that, alongside Sierra Leone’s denizens, they too were participating in the same activity of listening to the same set of songs. This is, perhaps, what communion looks like when you’re 5,000 miles away from home.

Music also provided the occasion for remembrance. So often, a song would bring about a strong emotional response, usually homesickness. That’s when the stories would spill out – tales of who they once were and the events and people who had shaped their lives. Spurred on by these memories, they would undertake a sort of evocation of Sierra Leone; an attempt, I guess, to subdue the distress of such a prolonged, unanticipated separation. They would reconstruct Sierra Leone through anecdotes, words; like gods creating a world through language.

You memba dat tem wae…?

Yes, ar memba wae…

Oh, God! Those days were sweet.

There was a tendency to personalise Sierra Leone, to describe it in accordance with what they desired and so painfully missed. But I wasn’t born in Sierra Leone, and haven’t spent more than 10 days there; so such a retelling of home, one that responds to the emotional needs of others, was, at times, alienating. It felt like a parade of experiences that I could mine for cultural insight and pride, but ultimately never participate in.

This is diaspora – or, at least, my experience of it: a constellation of individuals, associated with Sierra Leone, negotiating their place in the world.

Diaspora isn’t simply a migration from one’s home. It’s a network of relations based on memory, cultural reproduction and transmission, and the social dynamics that support them. Diasporas occur when political and social instabilities provoke flight – when, say, a dictator emerges or an environmental disaster takes place. After the initial dispersal (the word itself comes from the Ancient Greek διά and σπείρω, meaning ‘sowing across’ or ‘scattering’), individuals collect in two or more locations outside their homeland, where they form communities that are held together by a shared history and the complexities of uprootedness. These communities then participate in transnational networks that connect specific diasporas with each other – the Dominican community in New York with the Dominican community in Madrid, for example – as well as with their place of departure. In this regard, diaspora differs from exile, another form of dislocation, which is individually endured. (As the Palestinian American intellectual Edward Said once observed: ‘In a very acute sense exile is a solitude experienced outside the group …’) Still, like exile, it is marked by natal and cultural alienation, adaption and defiance, and also creativity.

Creativity is integral to diaspora, because it is impossible to replicate home cultures entirely in adopted areas of settlement. My parents may dance to highlife at community events. They may even do so in ways similar to when they were in Sierra Leone. But their fellow merrymakers would most likely include dance styles that are particular to Washington, DC, Atlanta, London and other places that host Sierra Leonean diasporas. (It’s worth mentioning that highlife is a West African musical form that is hybridised and draws from diverse influences, African and non-African alike. There are also variations of highlife and contested histories that situate its origins in different anglophone West African countries. These disparities challenge any claims of cultural purity, most certainly with regard to highlife, but by extension to popular art and culture in general.) Likewise, West Indians may attend and participate in the annual Notting Hill Carnival in London, but the festivities there would not be facsimiles of what they knew in Trinidad, Barbados or Grenada. They would borrow from different West Indian dance and music traditions, which themselves are heterogenous and creolised, and are then filtered through a robustly multicultural London.

Diasporic cultures and their productions may not be the real thing, but they’re not bastardised versions either

Culture is defined as a collection of beliefs and values that help maintain a harmonious social environment. When we inherit new environments – as is the case of diasporas – cultural adaptions and alterations occur. Home cultures don’t disappear altogether, but lay the grounds for complex, entangled and innovative ways of moving through life. In other words, they help form new, diasporic cultures. In his meditation on Caribbean diasporas in the UK, ‘Thinking the Diaspora: Home-Thoughts from Abroad’ (1999), the Jamaican-born cultural critic Stuart Hall explains this development vis-à-vis British-produced dancehall music and culture. He notes that:

[D]ancehall music and subculture in Britain was, of course, inspired by and takes much of its style and attitude from the dancehall music and subculture of Jamaica. But it now has its own variant black British forms, and its own indigenous location.

Dancehall’s transformation was inevitable, according to Hall, once it became diasporic. It was bound to become home-grown and ‘impure’ – influenced by the conditions and aesthetics that come with putting down roots in Britain. As such, the variant that emerged isn’t mere replica, which runs the risk of being insipid, inaccurate or, all in all, less than. It is a mode of expression born of deterritorialisation that embodies and articulates its very conditions.

So, diasporic cultures and their productions may not be the real thing, but they’re not bastardised versions either. They’re unique outcomes of fraught creative processes. Hall makes this clear about UK-based dancehall music and culture (and, throughout his career, about Black vernacular music at large). He presents similar thoughts about Caribbean cultures, which, in essence, are diasporic:

Our societies are composed, not of one, but many peoples. Their origins are not singular but diverse. Those to whom the land originally belonged have long since, largely, perished – decimated by hard labour and disease. The land cannot be ‘sacred’ because it was ‘violated’ – not empty but emptied. Everyone who is here originally belonged somewhere else.

Hall hints at a Caribbean history that involves violent ruptures and closures, as well as forced convergences of seemingly different people: settler colonialism all but killed off the original inhabitants. The slave trade brought Africans to the region to live as human chattel. Chinese and South Asians worked in sugarcane plantations as indentured servants. And Levantine groups, fleeing religious persecution and poverty, literally set up shop(s) in the Caribbean, where they could attain more security and prosperity. These migrations and settlements, and the interculturations they bred, caused, as Hall put it, a ‘distinctiveness’ in Caribbean cultures, one that is ‘the outcome of the most complex interweaving and fusion in the furnace of colonial society’.

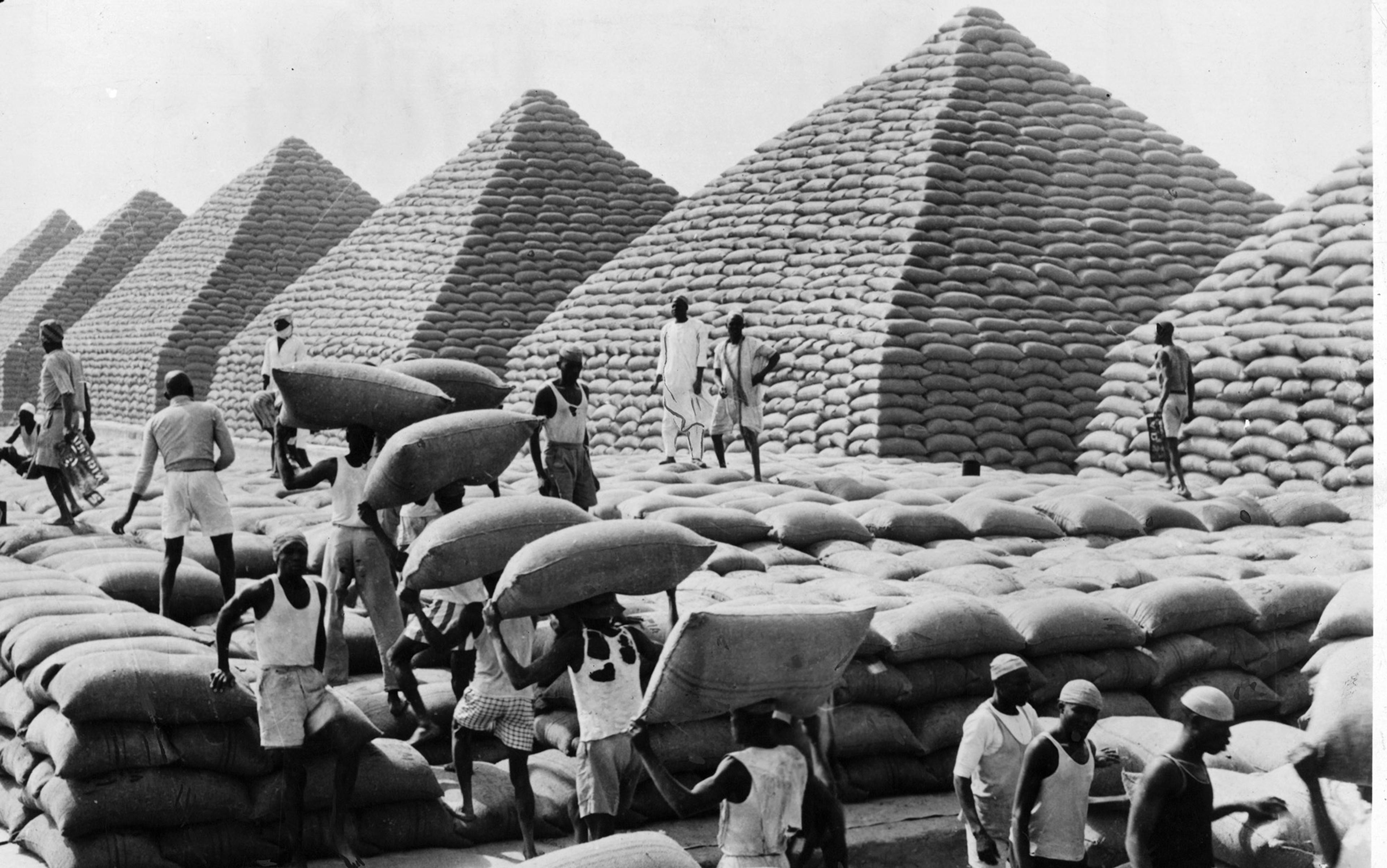

The furnace of colonial society: because the Indigenous populations had declined in the colonies and the imported Europeans couldn’t fulfil the economic desires of the ruling elites back home, European heads turned their sights to Africa. For a period of around 400 years, more than 12 million Africans were abducted from their native lands to be used as instruments of labour in the plantations, businesses and homes of the ‘New World’. Just under 2 million died along the way. These Africans came from diverse ethnic, cultural and linguistic backgrounds; but were bound together through physical violence and coercion. All the while, they were forced to contend with their European slavers and the European-style institutions they created. For these Africans and their descendants, cultures did not remain intact. They could not remain intact because kinship ties were all but severed, and cultural erasure was a strategy used by slavers to disorient the enslaved. Not to mention, the very survival of the exploited and displaced depended on cultural flexibility. Retentions endured, of course. Vestiges of past cultural lives in Africa enriched ‘New World’ food, music, religious practices, etc. But, ultimately, the enslaved had to and indeed did create new diasporic cultures to respond to the exigencies of their everyday lives.

It may seem that the formation of these independent cultures would result in a complete disconnect from Africa – that the diaspora and the continent would become distant entities. This, however, is not the case. Scholars, like Tsitsi Ella Jaji, have rightfully noted that African and Afrodiasporic cultural interconnectivities emerged from the ruptures of the transatlantic slave trade, and they continue to develop to this day. This means that culture doesn’t flow strictly from Africa to the diaspora, as scholars, like the American anthropologist Melville J Herskovits, once believed. Rather, interactions exist; exchanges occur; ideas, materials and expressions are redescribed, remixed and repurposed to fit needs on both sides of the Atlantic.

Take the music and dance tradition called goombay. It is Afrodiasporic, having its roots in Jamaican slave societies. But it is also African. It derives from African sources and has been performed in West and Central Africa since 1800, when a group of several hundred Trelawny Town Maroons were repatriated to Freetown, Sierra Leone.

In an attempt to suppress slave revolts, the British banned the usage of cylindrical drums

Goombay’s reach is wide, so wide in fact that it has surfaced in more than 20 countries throughout the Caribbean, North America, and Africa. The diverse spelling of its name alone – gumbé, gome, gube, goumbé and so on – bears evidence of its itinerant and, consequently, diasporic nature.

It is unclear exactly where the word goombay came from or when it first appeared. We find its earliest mention, though, in a three-volume study by the slave-owner and historian Edward Long, The History of Jamaica (1774). While discussing Black musical activity, he notes the usage of ‘The goombah … a hollow block of wood, covered with sheep-skin stripped of its hair.’ What Long describes is the goombay drum, the beating heart of the music and dance phenomenon. This drum distinguishes itself from other African drums in that it is not carved, but requires carpentry efforts; and it is square framed, as opposed to the usual cylindrical drums. It more closely resembles a stool or a box. This shape owes to the ingenuity of the captured Africans, who had to navigate British anxieties while maintaining methods that permit self-knowledge, as well as knowledge of others in their close proximity and the world beyond. In an attempt to suppress slave revolts, the British banned the usage of cylindrical drums, which were used in religious practices and for insurgent communications. The goombay drum, however, with its inconspicuous architecture, continued to preserve histories, transmit values, convey messages and assert African and Afrodescendent identities, unbeknown to the colonialists.

In early 19th-century Jamaica, the goombay drum featured in an array of social and religious practices and events, including those associated with myalism. Myalism was a movement that drew from West African religions and thrived during slavery and the early emancipation period. Its principal tenets were to fight against evil and to keep alive the connection between humanity and the ancestors. Spiritual possession, known as myal, was key. Ancestral spirits would enter a human medium, coaxed along by myal songs and rhythms sounded on the goombay drum. The possessed would then enter a forest, collect rituals items, such as herbs, and use them to heal spiritually afflicted individuals and/or circumstances. In this way, the goombay drum participated in the maintenance of communities and the wellbeing of individual lives. It also made history productive, by bringing it into the present moment to ameliorate present troubles.

Given that myalism both relied on and promoted Black agency, it’s unsurprising then that Jamaican Maroons conducted myal ceremonies, which they called Kromanti Play or Kromanti Dance. The Maroons were descendants of runaway Africans and Creoles – creole, as in born in the colonies – who had escaped from slavery in the 17th and 18th centuries and had set up autonomous communities throughout Jamaica’s wild and mountainous interior. Early on in their formation, they were thorns in the colonial side. Not only did they inspire others to escape the slave system which, in turn, disrupted plantation production, but they also conducted nighttime raids on neighbouring plantations, which thwarted agricultural expansion. To add to this, they engaged in guerilla warfare and mastered the land to an extent that surpassed the colonial militias. This made them damn-near inaccessible and difficult to root out.

With both parties struggle-weary, in 1739 a 15-article treaty was signed that gave the Maroons – first the Leeward Maroons, then the Windward ones – a degree of sovereignty in exchange for, among other things, their help in suppressing insurgencies and returning runaway slaves. (Certain Maroon leaders reject the notion that their forebearers wilfully delivered runaways back into slavery. They argue that trust wasn’t easy to come by, thanks to the colonial policy of divide-and-conquer. Prior to the 1739 treaty, Maroon communities were vulnerable to betrayal, particularly by the ‘Black Shots’, military forces made up of enslaved persons who aligned themselves with the British in exchange for money, freedom and other benefits. With this in mind, the Maroons could not readily accept just anyone into their settlements, even after the treaty afforded them some security. They did accept a few runaways though, but only after they proved themselves to be loyal. There’s also the issue of language: according to one contemporary Maroon leader, his ancestors may not have fully understood what they signed up for. Their command of English may have been lacking. Whatever the case may be, these varied accounts remind us that historical narration is never an objective retelling of ‘the way things were’. It is personal and contingent upon who is doing the remembering and how they remember the events.)

Time came when persistent racial abuse led to revolt, and fighting resumed once more. Despite a valiant effort, the Maroons – the Trelawny Town ones – were defeated by the British in 1795. And though Major General George Walpole, the commanding field officer of the British military forces, had promised that they would remain in Jamaica as long as they complied to certain demands – ask for the king’s pardon, return runaway slaves, and relocate to another part of the island – in 1796, 568 Trelawny Town Maroons were loaded onto a ship, some in chains, and sent off to Nova Scotia in Canada.

What of Jamaica did they bring with them? Did they practise Kromanti Play? Did they use the goombay drum? Did they fashion it out of black spruce? Or balsam fir? Records, scant as they are, about the Maroons’ four-year stay in Nova Scotia offer little insight into their cultural and artistic expressions. What is certain, however, is that Nova Scotia was cold and miserable, and that certain religious rituals survived, despite their dislocation and Canada’s harsh and foreign climate. This occurred to the frustration of the local authorities, who felt obliged to reform the Maroons, to bring them into British modes of normativity and conduct. To make them passive, submissive and loyal.

Finally, in 1800, the Maroons were repatriated to Freetown, Sierra Leone. By this time, the port city was already a hub for Afrodiasporic settlement. For example, the Black Loyalists, formerly enslaved African Americans who had fought on the side of the British during the Revolutionary War – they had been promised freedom, and had subsequently sought refuge in Nova Scotia – had made their way from Halifax to Freetown in 1792, eight years prior to the Maroons.

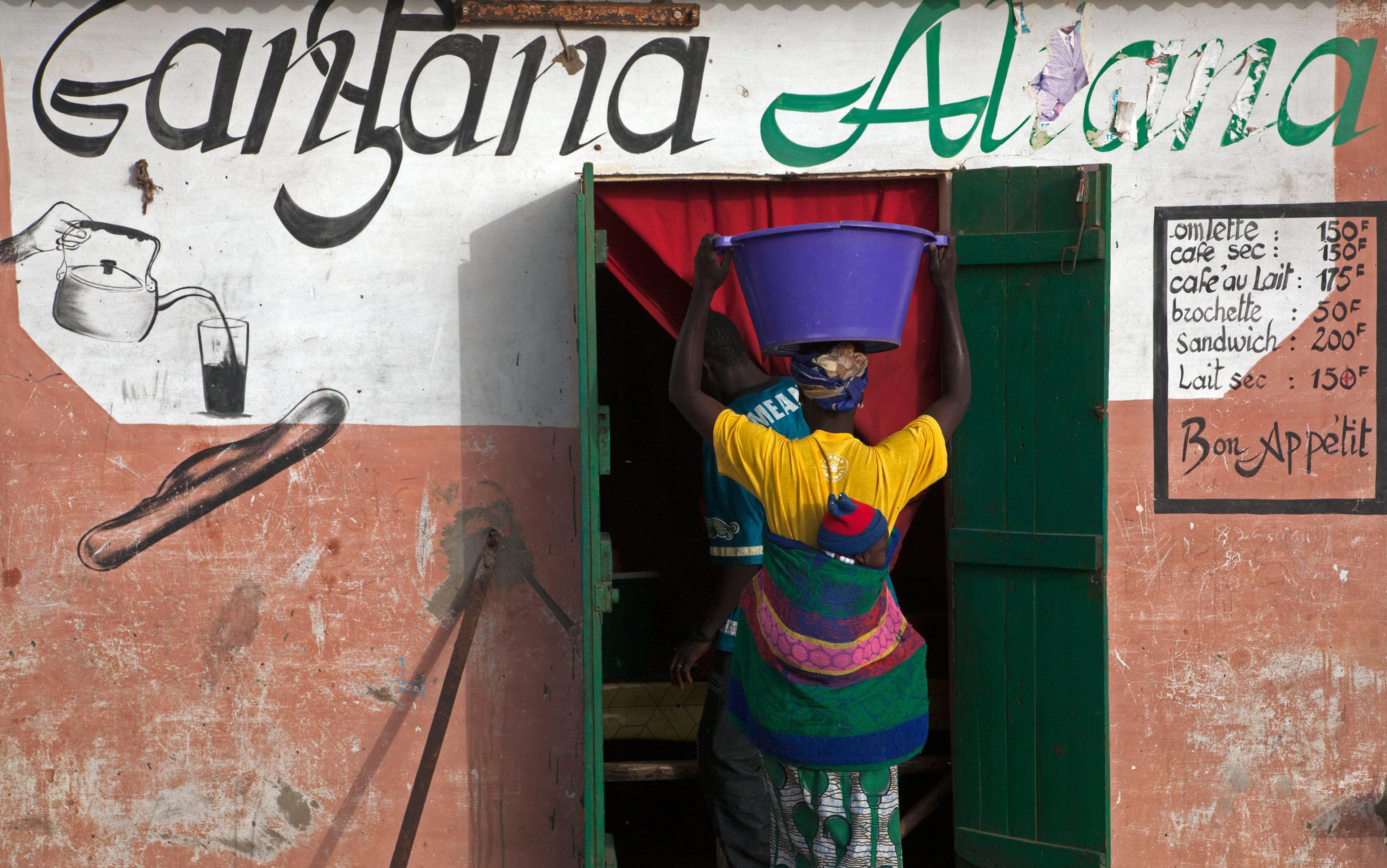

To live in Freetown in the 1800s – and the same rings true today – was to belong to a highly cosmopolitan society. There were the Sherbro, Temne, Mandinka and other non-diasporic groups who had long populated the Freetown Peninsula. There were the Black Loyalists, the Maroons and the ‘Black Poor’ of London. There were manumitted Africans, ‘Kru Boys’ and naval sea workers. By the second half of the 1800s, there were South Asian and Syrian (later, Lebanese) traders, the latter of whom initially hawked coral beads, before expanding into other enterprises, including the diamond trade. If Stuart Hall conceived of the Caribbean cultural identity as ‘syncretised configurations’ that resist binary apprehension, then the same could be said about the Freetownian cultural identity, which is creolised, malleable and ever-evolving.

Goombay may have helped shape the Krio identity, but not all Krios identified with goombay

In the midst of this diversity appeared goombay, which by the mid-1800s was considered a drum, and a popular music and dance genre. It also seemingly lost its spiritual register. This shift can be read vis-à-vis the formation of the Krio identity. The Krio are an ethnic group comprised of Black settlers, Maroons and liberated Africans, or people who had been captured and enslaved along the West African coast but were freed when British patrols intercepted the ships they were held on before they embarked. The process of forging this singular identity was complex, given how culturally heterogeneous each group was. This is especially true of the liberated Africans, whose population stretched from the historic Gold Coast to as far east as Mozambique. Music and dance then became a medium through which these varied people could coalesce. For, as the anthropologist and goombay scholar Kenneth Bilby notes: ‘danced interethnic encounters must have been one of the main theatres in which ethnic identities were performed and renegotiated.’ He adds, ‘and there can be little doubt that gumbe drummers continued to be enlisted for many such gatherings.’

Goombay may have helped shape the Krio identity, but not all Krios identified with goombay. The upper echelon of Krio society, which fancied itself as ‘Black Englishmen’ found the music and dance form unsavoury. It was a far cry from the Victorian tastes they were supposed to model. This dislike is made apparent in the article ‘Our Native Manners and Customs’ (1876), published in the newspaper The Sierra Leone Independent. There, a Mr James A Fitz-John laments: ‘So are refinement and decency forcibly kept back amongst us, while most unite in lewd, unseemly, and barbarous customs, of which the jig known here as the “Gombeh” is very far from being the least unbecoming.’ He continues:

‘Gombeh’ then is the star that attracts the most dissipated and the meanest ruffians of our country, it’s the magnet that draws the low and foul-mouthed wantons, and the noisy and brawl-seeking wharf boys of our city. At the rolling of the drums, churches and chapels are forsaken, classes and everything else are flung to the winds, and all rush to display their peculiar talents in that line.

So goombay, as Fitz-John conceives of it, is a nuisance. It leaves colonial classrooms empty and churches without congregations. It hinders the growth of morality and spits in the face of a Western notion of civilisation. Perhaps worse still, it undermines the safety and the social and material advancement of a people who had once endured so much hardship. It keeps them from being, as the Krio historian Akintola Wyse put it, ‘the beacons of light in darkest Africa’.

Debaucherous or not, goombay spread throughout West and Central Africa by way of Krio migrants. It took root in creolised societies and, conversely, faltered in spaces where Indigenous groups dominated. In these cases, goombay was vulnerable to indigenisation. Nevertheless, it laid the grounds for several popular musical forms, such as highlife, makossa and palm-wine music. And it remains relevant, with bands like Wulomei and Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars using it to contemplate such themes as nation and cultural pride.

Goombay teaches us that the relationships between Africa and the Afrodiaspora continue to grow and deepen. This occurs even unbeknown to the very people who are impacted by them. They are not simplistic, either. They are productive, ever-changing and always open.

I imagine that, for my parents, goombay will always be a path home. It reunites them with precisely those emotions and experiences that sustain them as Sierra Leone changes and they grow old outside of it.

And for me? Maybe I write this essay on goombay to personalise Sierra Leone, to lay upon it my thoughts and needs. And maybe, if I do this enough, if I write and write about diaspora and Sierra Leone, one day I’ll write my way home.