Listen to this essay

21 minute listen

In early March 2024, an expert panel of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) had a vote to settle a question that had vexed geologists for years: are we living in the Anthropocene, ‘the human age’? The result of the vote was a clear negative. In the realm of geological disciplines, the debate that endured for decades is basically over. However, the term ‘Anthropocene’ has become deeply ingrained in the public imagination and will not be simply erased. And it still has currency, but it needs to be broken loose from entrenched debates that carry unnecessary baggage. The Anthropocene is a prism through which we can examine the multifaceted history of human activities on this planet, and the spectrum of our potential futures.

The idea of humans as planet-altering agents has long roots. The American diplomat and philologist George Perkins Marsh proposed in Man and Nature (1864) that humanity had become a geological force, on a par with the most powerful forces of nature. The term ‘the Anthropocene’ was proposed by Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in 2000, in the multidisciplinary field of Earth System Science:

Considering these and many other major and still growing impacts of human activities on earth and atmosphere, and at all, including global, scales, it seems to us more than appropriate to emphasize the central role of mankind in geology and ecology by proposing to use the term ‘anthropocene’ for the current geological epoch. The impacts of current human activities will continue over long periods.

The idea was taken up in stratigraphy, the branch of geology that studies rock layers and is responsible for classifying the geological time of Earth. In 2009, an official process was begun to determine whether the Anthropocene would gain the status of a geological epoch. Although an epoch is the second smallest unit in the hierarchical classification of geologic time, past epochs have spanned millions of years, whereas the current epoch, the Holocene, is just 11,700 years old. Proposing a new epoch so soon was controversial among stratigraphers, to say the least. The newly formed Anthropocene Working Group would tackle the issue.

In official stratigraphic definition of epochs, a distinct starting point has to be decided. Every epoch begins and ends at a clear point in time. Also, a geological marker, ‘the golden spike’, has to be found at some specific time and place. For the current Holocene epoch, the marker is based on a change in deuterium excess values, and the primary location is a borehole in Greenland.

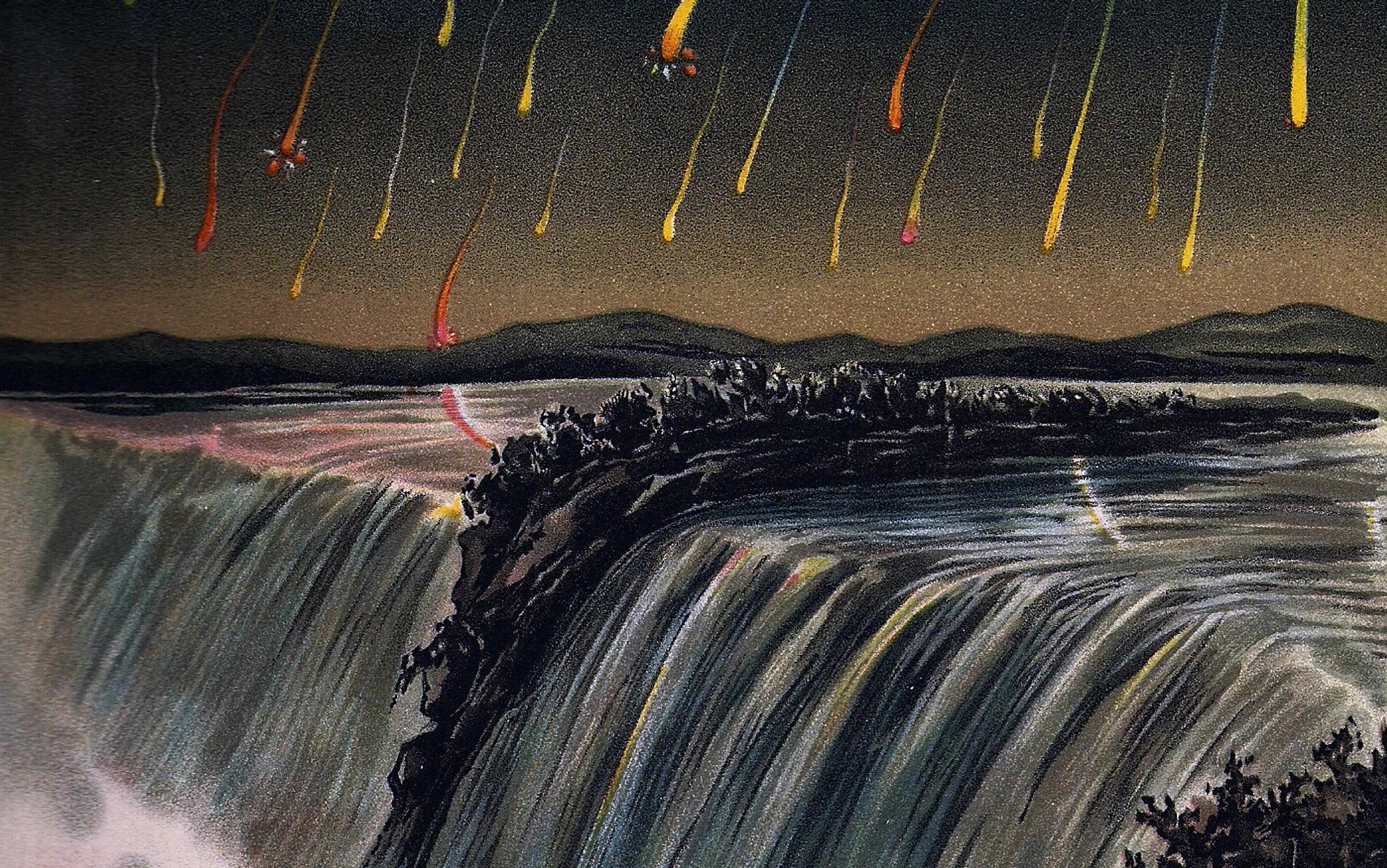

Geologists are not silly, of course. They do not claim that an epoch spanning millions of years literally began at some specific point in time (or place): this is an artefact of the system of classification. But a similar determination would have to be made for the Anthropocene for it to qualify even for the ICS vote. There were a number of candidates for this: the Columbian Exchange, the Industrial Revolution, or ‘the Great Acceleration’ from the 1950s onwards. The Anthropocene Working Group chose the first atomic bomb tests as the marker, and Crawford Lake in Ontario, Canada, as the location of ‘the golden spike’.

To be clear, this determination was never intended as the answer to the question ‘When did humans begin to alter the environment on a planetary scale?’ It was known by most if not all involved that human activity had changed the face of the planet in multifarious ways over centuries, even millennia. However, at some stage in history, the effects of human activities had accelerated significantly, and that is why ‘the Great Acceleration’ became a focal point in the winning proposal. To determine this, the classification system demanded a single point of origin.

In 2016, the group made its recommendation that the Anthropocene should be considered as the new epoch. This recommendation was later forwarded to higher ICS organs for consideration and voting. A series of votes was expected, but the proposal was rejected early on in the process in March 2024. Although technically the proposal could be renewed in a decade, for now it seems that the debate is over. In stratigraphic terms, we are still living in the Holocene.

Despite being officially declared dead, however, the term ‘Anthropocene’ is very much alive. Early on, it broke out of the confines of stratigraphy and was adopted widely in public discussion, in the arts, and also in various other sciences, both natural and social. Myriad scientific journals, conferences, artworks and novels still carry it forward.

But how should the term be understood now, when its lifetime as an official geological concept is over? Should we stop using it, or define it in a new way? I believe that the term still has value, but it needs to be freed from certain entrenched positions that carry unnecessary baggage.

A problem in the wider cultural discussion over the Anthropocene has been that the stratigraphic view has been somewhat misinterpreted. Instead of understanding ‘the golden spike’ as an artefact of classification, it has been deemed as a statement of existential importance. Especially in social and human sciences, determining the point of origin of the Anthropocene has been repeatedly understood as pointing to historical guilt.

According to one common line of criticism, the very idea of the Anthropocene, ‘the age of humans’, risks universalising the issue and slipping into misanthropy. Are all humans everywhere and at all times equally to blame? Was the path towards the Anthropocene cleared with the invention of fire, or the planting of the first fields, or at the first iron forge? Are humans truly ‘a virus’ of nature as proposed by Agent Smith in The Matrix movie franchise, or by some ‘neo-Malthusian’ environmental thinkers?

If the Anthropocene originated in the 1950s, would it not let colonialism or capitalism off the hook?

The concept ‘neo-Malthusian’, named after Thomas Malthus (1766-1834), can be used narrowly or loosely, but in this case, it refers to views according to which the size of the human population is the fundamental defining factor and the root cause of environmental problems. According to this view, humans are in an inescapable zero-sum game with the rest of nature. For such thinkers, determining the Anthropocene as the ecological original sin is not a problem. Paul R Ehrlich, who co-wrote the book The Population Bomb (1968) with Anne H Ehrlich, is a prime example here: according to him, the ‘optimum’ human population would be fewer than 2 billion.

Neo-Malthusian environmental ideas have also been embraced by xenophobic or outright racist groups, since they seem to justify focusing all attention on the areas where the human population is still growing, and belittling the importance of wealth inequality, historical plunder, resource extractivism and the wild differences in per-capita consumption and pollution.

For these critics, the idea of the Anthropocene is inherently compromised or biased towards such thinking. It is deemed fundamentally ahistorical and apolitical, blind to the differences between and within societies. What about the Columbian Exchange, or the Industrial Revolution? Are they part and parcel of the same undifferentiated ‘human era’?

Another line of criticism has been conversely aimed at the historically specific determination of the origin point at ‘the Great Acceleration’ of the 1950s. If the Anthropocene is seen as originating in so late a date, would it not let the earlier phases of colonialism or capitalism off the hook? This criticism is based on the wider view that fundamental societal transformations are not point events but longer processes. For example, the Industrial Revolution had roots in the earlier manufactures and even earlier changes in agriculture. And the Green Revolution cannot be explained only by new fertilisers and other agricultural technologies: it stems also from earlier neocolonial groundwork. Thus, the deeper political foundations of the Anthropocene need to be excavated.

Such accusations have disturbed many stratigraphers, who feel that ‘politicising’ such a technical debate is unwarranted. For them, dividing history with a gold spike would not mean that everything began then. Of course different kinds of environmental changes have taken place in different eras, and there are significant differences of scale and ecological dynamics between them. But in the stratigraphic playing field, a temporal signpost has to be stuck somewhere, and it should not be interpreted as placing exclusive historical blame. This counter-critique has been both justified and naive, as it is obvious how the geological debates resonated with the other existing ideas about the environmental crisis. Scientific debates do not take place in a vacuum.

In order to tackle both the ingrained misanthropy and the simplistic historical views, new terms have been proposed to supplant the Anthropocene. A plethora of competing ‘-cenes’ and root causes of environmental destruction have followed.

The Swedish human ecologist Andreas Malm proposed ‘Capitalocene’ in 2009, arguing for the centrality of capitalism in the planet-altering activities. The idea has been taken up by many others, such as the environmental historian Jason W Moore. And in their book The Shock of the Anthropocene (2016), the French historians of science Christophe Bonneuil and Jean-Baptiste Fressoz proposed ‘Anglocene’:

The overwhelming share of responsibility for climate change of the two hegemonic powers of the 19th (Great Britain) and 20th (United States) centuries attests to the fundamental link between climate change and projects of world domination.

Several researchers who highlight the entangling of human life with technology have argued for ‘Technocene’. The renowned feminist scholar Donna Haraway and the anthropologist Anna Tsing, author of The Mushroom at the End of the World (2021), have pointed out the centrality of plantations in colonial history, proposing ‘Plantationocene’. Haraway has another possibility too, ‘Chthulucene’, but don’t worry, she is not proposing that our era is determined by Lovecraftian horrors (she named the -cene after a species of spider). The name Chthulucene detracts from the competition between historical points of origin: instead, Haraway points to the importance of fuzzying the boundaries between human and nonhuman, and trying to live with the troubles we have inherited.

The competing ‘-cenes’ become mutually exclusive alternatives. Choosing one is interpreted as a choice against the others

The competing ‘-cenes’ do point out important alternative viewpoints for examining the (geologically) recent history. But the discussion is burdened by an unnecessary notion of exclusivity: the main culprit, the root cause, has to be located somewhere – somewhere else than in humanity itself, but at some clear and distinct source anyway.

This is a recurrent feature in environmental thinking. Even though environmental problems are legion and not a unified whole, there is a strong tendency to totalise them into an undifferentiated whole. One problem, only one root cause. The competing ‘-cenes’ thus tend to become mutually exclusive alternatives, different determinations of the root cause of the environmental crisis. Choosing one is readily interpreted as a choice against the others.

This is a serious problem, as it narrows our understanding of ecological issues. With climate change, one can fairly justifiably point to the rise of capitalism and industrialisation as the root causes, because most of the greenhouse gas emissions have taken place since c1750, in an accelerating fashion. But the global spread of monocultures, which has resulted in a narrowing selection of domesticated plants and species, is a key dimension of biodiversity decline. And it has a much longer pre-capitalist history. On the other hand, the depletion of the ozone layer was down to a very specific selection of chemical compounds that could have been developed in a very different world, and it could have remained undetected without sophisticated satellites. The hundreds of aboveground nuclear tests were fed by the Cold War. And so on.

Now that the official Anthropocene narrative is over, now that the stratigraphic, natural scientific determination can no longer be used as a touchstone, there is a good opportunity to rethink this issue. We should get away from the territory of alternative and competing points of origin, from the debate between mutually exclusive root causes, and look at the whole thing as a varying historical process.

Some inspiration can be drawn from the late stage of the stratigraphic debates. In 2021, a group of scientists proposed that the Anthropocene could be more fruitfully understood not as an epoch but as ‘an event’. In geologic time, events are processes of change, which contribute to transformations of the global ecological systems. They are diachronous and dynamic, rather than specific periods with a beginning and an end. In 2023, the same scientists noted that the epoch view ‘fails to account not only for the diachronic nature of human impacts on global environmental systems during the Late Holocene but also the spatial heterogeneity of those impacts.’ In their view, the Anthropocene is a development that has endured for millennia and is still going on.

Events also differ from epochs in that, in stratigraphic terms, they need no formal ratification nor a determination of ‘the golden spike’. The causes and dynamics can be more multifarious – precisely the point made above about the historically layered nature of environmental change wrought by human activities:

Moreover, human processes that had or have significant impacts and which are reflected in these records are not isochronous but by their very nature are time-transgressive. This is equally the case whether it be the origins of agriculture, the beginnings of urbanisation, the colonisation of the Americas, the Renaissance, the Industrial Revolution, or the Great Acceleration – all important events in their own right and, collectively, part of the broader Anthropocene Event.

What kind of things have been events? The Great Oxidation Event, the remarkable rise of oxygen in Earth’s atmosphere 2.3-2.5 billion years ago, is one. Another example is the Great Ordovician Biodiversity Event, an explosive diversification of marine life. In biological sciences, mass extinctions are also called ‘events’ – not precisely the same thing as geological events, but extinction events too are long and multifarious processes that transform the very fabric of life.

There are changes, and then there are changes, and significant differences between them should not be shrouded

The debate over whether we are living in the midst of a ‘Sixth Mass Extinction Event’ is still going on. It is important to note that our current situation does not compare with ‘the Great Dying’, or the Permian-Triassic Extinction Event, and let us hope it never will. It is approximated that 70 per cent of terrestrial vertebrate species and 80-90 per cent of marine species went extinct back then, and life was much poorer for millions of years. It was touch and go for life on Earth. The only human thing that could perhaps cause something like that would be a massive nuclear war. Nevertheless, it is clear that biodiversity is being radically endangered on many levels (genetic diversity of populations, loss of populations, extinction of species, and the degradation or fragmentation of ecosystems). We are in the midst of a torrential transfiguration of life on Earth.

On the one hand, it is crucial to note that human-induced ecological changes clearly have grown to become increasingly global in scale during the Great Acceleration. Extraction of natural resources, land use change and various forms of pollution have increased by orders of magnitude. So there clearly are differences within the millennia-spanning event. The Great Acceleration is a world-historical hinge point after which things have become very different. The fossil-fuelled, technologically complex and (mostly) capitalist human societies have truly become an agent of change that compares with the great upheavals of deep history.

This is an important point: ‘humans have always changed their environments’ is a truism that can too easily be used to belittle environmental concerns. There are changes, and then there are changes, and significant differences between them should not be shrouded. Something world-historically unique has taken place since the Second World War.

On the other hand, by focusing too much on this fairly recent history, we lose sight of the longer-term historical forces that have affected our world. The notion of the Anthropocene as an event, as a long-term process, allows us to keep in mind different rhythms of history at the same time: environmental changes that have roots closer to the surface and those that dig deeper. Why on Earth should anything so complex as our ecological peril have one root cause? This is what roots do, dig into many directions at the same time. This does not let anyone or anything ‘off the hook’, it means that we have to be mindful of both the younger and the older roots of our predicament, to look at a plethora of root causes.

For example: when we are focusing our gaze on climate change and plastic pollution, it is clear that the fossil fuel economies that have accelerated after the Second World War should be our prime concern. Decarbonising our economies is necessary, and most likely that will require deeper societal transformations not only in how we produce and consume things but also in the fundamental infrastructures (energy, traffic and transport, heating etc) and the ways we value things.

Perhaps the Sinocene? Robocene? Nanocene? One could continue this neologism bonanza to the point of ridiculousness

But even if climate change is successfully curtailed within ‘safety limits’, it will not necessarily be done in a way that will stop biodiversity decline. Some facets of that much more complex phenomenon clearly stem from the modern growth-oriented and extractive societal paradigm, but other facets have longer histories. Some are due to the specific ways our needs are provided for: for example dedicating 80 per cent of agricultural land to animal production. Most likely, getting back within sustainable ecological limits in this wider sense will take much longer than the decadal scale required by climate mitigation. The work of safeguarding the viability of Earth as a home will go on, perhaps in a sense forever.

To use the language of the competing ‘-cenes’, we have to be simultaneously mindful of the Plantationocene, the Anglocene, the Technocene, the Capitalocene, and of many others to come – perhaps the Sinocene? Robocene? Nanocene? One could continue this neologism bonanza to the point of ridiculousness, but the point is simple: we have to keep looking at various timescales and histories at the same time, to try to understand recent history and deep time concurrently. This is a crucial thing, irrespective of the nomenclature we choose.

Another way to look at this is to say that we are living in the ongoing process of the Anthropocene that has multiple currents and will take new and surprising (and perhaps more terrible) forms in the future. This is another virtue of the notion of the Anthropocene as an event: it is open-ended, it points not only to history but also to the future. We are in the midst of a fundamental process of transformation that can get much, much worse. The Anthropocene we see now may in the future seem quite hospitable.

Not only are we moving to a radically different planet, there is a temporal succession of alien planets looming in the future, and alternative trajectories to take. None of the paths to the future are free of problems, because the inherited baggage of history is heavy. A lot of damage has been done, and we have to live with that trouble, as Haraway and Tsing have stated. Some things have been irrevocably lost, and many other things will be lost, even in the best of all possible worlds. Whether the future sees a better or a worse-off world, a world-historical bottleneck needs to be squeezed through. Choices are made, every day, about the planet that humans will inhabit in the futures to come.

But the future lasts a long time. If the current human societies can get their act together, during the future stages of the Anthropocene Event, the planet may yet be a better place to live in than it is now. It may take centuries, and the result will not be a return to the past but a radically altered world. The key is whether humans and other creatures can still find it a world in which to thrive and create ever new futures.