The red-veined rocks of Bohuslän in western Sweden have one of the highest concentrations of Bronze Age art in Europe. I was lucky enough to see the carvings during a recent October visit. The site was set back from a road, which marked where the shoreline of the North Sea would have been when the figures were first inscribed, between 2,500 and 4,000 years ago. The petroglyphs had since been painted pillar-box red so that they’d stand out for tourists, and the bright colours and wobbly lines looked like an enormous child’s drawing. But what the scene lacked in elegance it made up for in energy. Bowmen stalked antlered stags among a fleet of longships, flowing into a procession of bulls and thick-bodied giants teetering precariously atop spindly legs. Land and sea, human and animal, swam in and out of view.

Bronze Age rock art in Bohuslän, Sweden, assumed to depict the performance of a ritual. Photo courtesy Wikipedia.

I found myself trying to create a narrative, some sort of lost epic, as if I were deciphering a Bronze Age cartoon. We don’t know why these inscriptions were made, or what they were meant to say. The blunt-limbed figures give no clue about where such a story might begin, or where it might end. But perhaps that tangled quality is the petroglyphs’ real message. The longships speak of a culture closely aligned with the sea; the many animals point to a strong affinity with nature. Similar sites on the Cornish and Iberian peninsulas indicate that cultural influences travelled along what the Beowulf poet would later call the ‘whale roads’, the open waters that connected Bronze Age Scandinavia to the rest of Europe for the purposes of war and trade.

We live in a similarly entangled age, in which our consumption of fossil fuels, nitrogen fertilisers, the cobalt in our smartphones, antibiotics, and plastic all bind us to faraway times and places. The world of the Anthropocene is made from this dense web of relationships, each of which leaves its imprint on the world of the future. Two hundred generations of humans have lived and died since the Bohuslän petroglyphs were chipped out of the granite, but they remain urgent and vivid, the evidence of a living presence. In their silence, they pose certain questions. How and why do we navigate the currents of time and of matter to communicate with the deep future? Is it our intentional signs and symbols that leave the most lasting marks, or our unintentional traces?

I live and work in Edinburgh, on the lip of the North Sea. I’ve come to see these waters as a kind of Anthropocene laboratory, somewhere that lets us peer at the long-term impacts of the way we’re living now. Its past can tell us something of our future. As the Pangea supercontinent was breaking up 200 million years ago, ancient bacteria and microscopic plants were trapped in what would become the sea floor. Sediments gradually covered them over, and the immense pressure and heat from moving tectonic plates slowly converted this organic matter into the fossil fuels for which the region is now famous.

Until the end of the last Ice Age a vast plain linked Britain to continental Europe; evidence of human presence has been discovered in the form of stone hand axes, dredged up from the sea floor in the south. Then, around 11,700 years ago, the glaciers that once smothered the British Isles in sheets of ice up to 2km thick began to melt, and the North Sea slowly emerged in its present shape – a shallow basin, edged by a deep trench where the sea meets the crenellated coast of Norway.

The North Sea’s temperate climate fostered a steady flowering of cultures and industries. The ebb and flow of all this activity and the material it generated has carried the North Sea out of its Holocene past and thrust it into the Anthropocene. Today, it’s one of the busiest shipping zones in the world. Container ships up to 400m long pass in and out of the port cities of Rotterdam, Antwerp and Hamburg, a moving tapestry of routes that weaves and unweaves itself over the surface the globe. Nearly 200 oil platforms and many more gas production plants perch in the water like giant wading seabirds. The coastline is dotted with petroleum refineries, power stations and industrial chemical plants, and forests of wind turbines have sprouted in its southern reaches. Plastic lines its shores, as well as the gullets of its fish and birdlife.

The plastics on Orust could remain on the beach as long as the rock warriors have been dancing in Bohuslän

After visiting the rock art in Bohuslän, our group travelled to a beach on Orust, the third largest island in an archipelago of 10,000 outcroppings that surround the Swedish mainland. Our guide was a marine biologist who’d grown up in the region, and watched as the waters and shores of his childhood became clotted with waste. As he shepherded us down to the shore, the pigeon-grey rocks made the primary colours of the plastic look all the more lurid. Among the seaweed and scraps of rope, a shred of blue net caught my eye. Its fine threads were only a millimetre thick. The mesh seemed as fragile as spider silk, but was so strong that I couldn’t pull it apart. Shorn of their proper context, these fragments pose their own, rather bathetic mystery. We don’t know their stories, but they are confoundingly familiar – banal, even, but still astounding in their abundance, and their capacity to travel and endure. Left undisturbed, the plastics on Orust could remain on the beach for as long as the rock warriors have been dancing on the granite beds of Bohuslän.

Nearly every piece of plastic that ends up in the ocean is probably still there. Our guide explained that what washes up on the beaches of the North Sea represents only a small fraction of the plastic that enters the water; almost all of it falls to the sea floor as ‘marine snow’. In the process, many creatures have had the opportunity to ingest it. In January and February last year, 30 sperm whales were fatally stranded along the North Sea coasts; of the 22 that were necropsied, nine had consumed plastic waste, including discarded fishing gear, a plastic bucket, and part of the engine cover of a Ford SUV. No one knows quite why the whales beach themselves. They might become disoriented by the toxic effects of pollution, or lose the thread of their hunting and migration routes because of noise from shipping and deep sea mining. Whatever the cause, these whales entered a part of the North Sea that isn’t deep enough. Stranded on the beach, their organs collapsed under the weight of their own unsupported bodies.

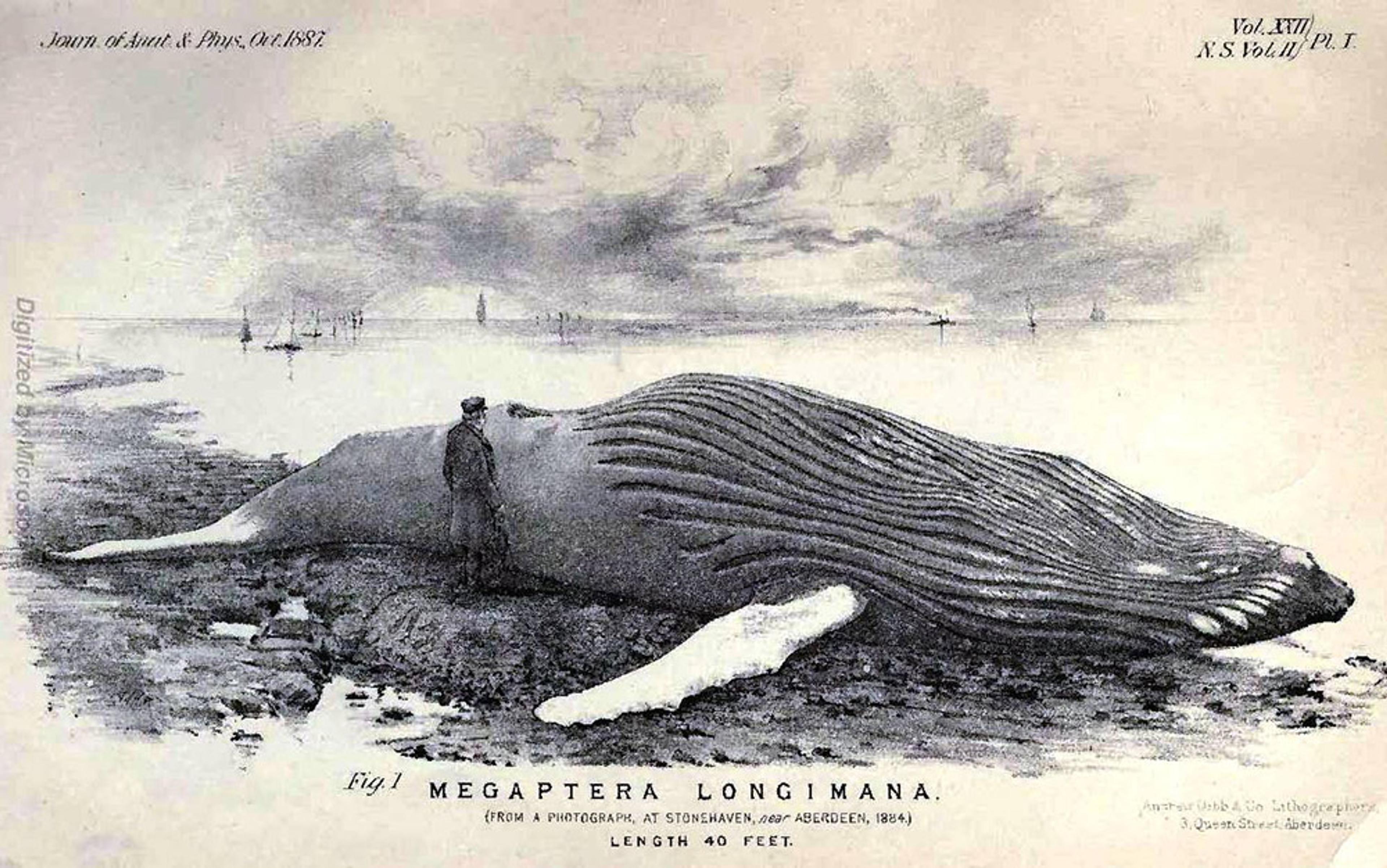

Not long after I returned from Sweden, I went to the beach near my home, at the estuary called the Firth of Forth. It’s a vibrant, working landscape, fringed with industry and speckled with bird life. The Firth has a long history of whale strandings, though I’ve been coming here for years and have never seen one. The very first account in English of a blue whale was published in 1694, describing an animal that was stranded in the Forth. In 1819, the fossil of a 72-foot blue whale was found at Airthrey on the coast of Stirlingshire, with a stone tool discarded beside it – evidence of what must have been an unimaginable bounty for the neolithic hunter who stumbled on the creature. In 2013, a minke whale beached itself here, and in 2013 a rare pod of 14 sperm whales was spotted in the Forth’s relatively shallow waters.

The Tay Whale, a humpback whale beached at Stonehaven in eastern Scotland in 1894. Courtesy Wikipedia.

In her essay ‘Findings’ (2005), the Scottish poet and writer Kathleen Jamie describes discovering a whale on a visit to Ceann Iar, one of the Monach Islands on the westernmost edge of Scotland. Dead for some time, partially sunken in its bed of sand and its eyes lost to scavenging gulls, the animal is uncannily out of place, a startling intrusion on human senses. ‘It was the heaviest creature I had ever seen,’ she writes, ‘dead and out of the water’s buoyancy, a massive failure.’ Ceann Iar is exposed to the raking winds and surges of the Atlantic, whose warm current courses west to east through the sub-arctic waters of Greenland before curving around Scotland and spilling into the North Sea below the southern tip of the Shetland Islands. On its way, the current picks up plastic debris gathered in the great garbage patch accumulating in the North Atlantic gyre, and decants it over the thousands of kilometres of beaches. Jamie writes that the beach that day was choked with domestic plastic: shampoo and toilet cleaner bottles, paint brushes, masking tape, shoes, and strands of the same ubiquitous polypropylene net I picked up in Orust.

Oddly, like the whale, this clutter of debris possesses a peculiar fascination for me. It’s ‘the bright garbage on the incoming wave’, as the Northern Irish poet Derek Mahon puts it. The crumpled drink cans and rotting plastic bags I see regularly at the Forth prick me with the sting of a certain connection. It’s the surprise of finding some familiar thing, washed clean of its history and set down in a place it was never meant to be. Often, the object is still imprinted with the names of branded goods it was used to sell, but wears little visible trace of the damaging processes of extraction and manufacture that shaped it.

From the point of view of their scope and utility, whale products were the plastics of the 19th century

Plastics have organic origins in the petroleum drawn from oil wells, such as those that pockmark the floor of the North Sea. During manufacture, their carbon atoms form strong covalent bonds. Bacteria that have evolved to decompose organic material simply don’t know how to process plastic, although a microbe known as Ideonella sakaiensis has recently been found that can consume PET (the principal material in plastic bottles). A typical disposable plastic container is in use for around 60 days before it’s thrown away. Yet this brief period falls on a line that runs from the deep past to the deep future: the 3.4 million years since the raw materials (oil) began to form, and the 10,000 or more years it could take for the plastic to degrade. Items whose basic ingredients were drawn from oil wells in the Arabian Peninsula or Ecuador, manufactured in China, and carried by Indonesian container ships for consumption in Britain and North America, now turn up on my doorstep in Scotland.

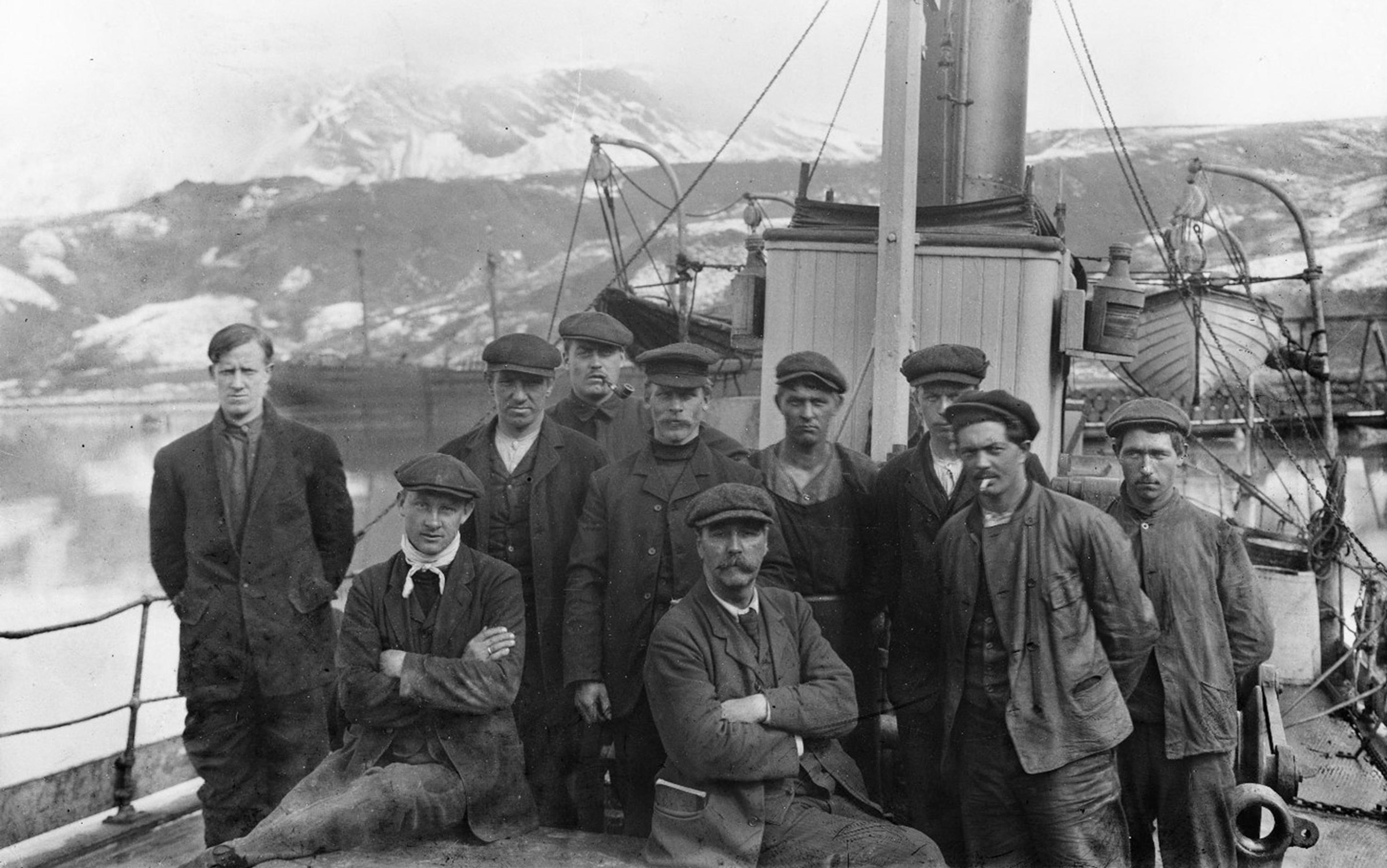

The same sea routes now carrying plastic were once busy with arctic whalers, pursuing the animal’s fabulous organic bounty. From the point of view of their scope and utility, whale products were the plastics of the 19th century. Whale oil is an incredible, fine, durable material, ranging in hue from a lucent honey to a waxy brown, used to make candles, soap, leather and glycerine. It oiled the clocks and lit the drawing rooms of the industrial age, and was deemed so vital to the production of military nitroglycerine that in 1916 the British government banned unlicensed trade in the stuff. Whale bones, meanwhile, were used to make stays, hoops, umbrellas and buttons. Even their excrement was highly prized by perfumers, among others: ambergris, a secretion of the sperm whale’s digestive tract, could fetch more per ounce than gold. Drained of their oil and stripped of all saleable parts, the headless corpses were usually tipped back into the water.

The first known whalers were Basque fishermen. They began hunting in the waters of the Bay of Biscay around 1,000 years ago, before advancing to the North Sea. Industrial whaling took off in the middle of the 19th century thanks to two key innovations from the United States: a harpoon that could carry small explosive charges; and a device designed by Lewis Temple, an African-American inventor born into slavery, that consisted of a pivoting arrow-head which implanted itself deep into the whale’s blubber and prevented the creature from slipping off. Over the course of the 19th century, sperm whale numbers dropped by two-thirds, and up to 90 per cent of blue whales were wiped out. The writer Herman Melville compared the pursuit of whales with that of the buffalo, which once ‘overspread by tens of thousands the prairies of Illinois and Missouri’, and wondered whether, like the buffalo, the whale could ‘long endure so wide a chase, and so remorseless a havoc’.

But the peak of whaling was another 100 years away. More whales were killed worldwide in 1951 than in the preceding 150 years by Yankee whalers. Whale oil continued to be an essential ingredient in the postwar economy, furnishing consumers with lubricants, paints, detergents and inks; crayons and cat food; hydrogenated margarine and ice-cream; vitamin D supplements and automobile brake fluid. Today whales are largely protected by international treaties, though Norway and Iceland refuse to recognise the international moratorium on commercial whaling. Still, about 2.9 million whales were killed in the 20th century.

The modernist poet Basil Bunting is one of the great chroniclers of the changing face of the North Sea. Born in a village outside Newcastle in 1900, Bunting was imprisoned as a conscientious objector during the First World War, after which he became an intimate of Ezra Pound (W B Yeats called him ‘one of Ezra’s more savage disciples’). Later, Bunting went on to be a military intelligence officer and correspondent for The Times in Persia. His life followed a series of currents – an occasional music critic and literary secretary, Bunting was also a herring fisherman, shepherd and airman, and once sailed solo to Montreal from Middlesbrough. In the mid-1960s, living in diminished circumstances back in the north of England, he began work on Briggflatts (1966), his great verse-memoir.

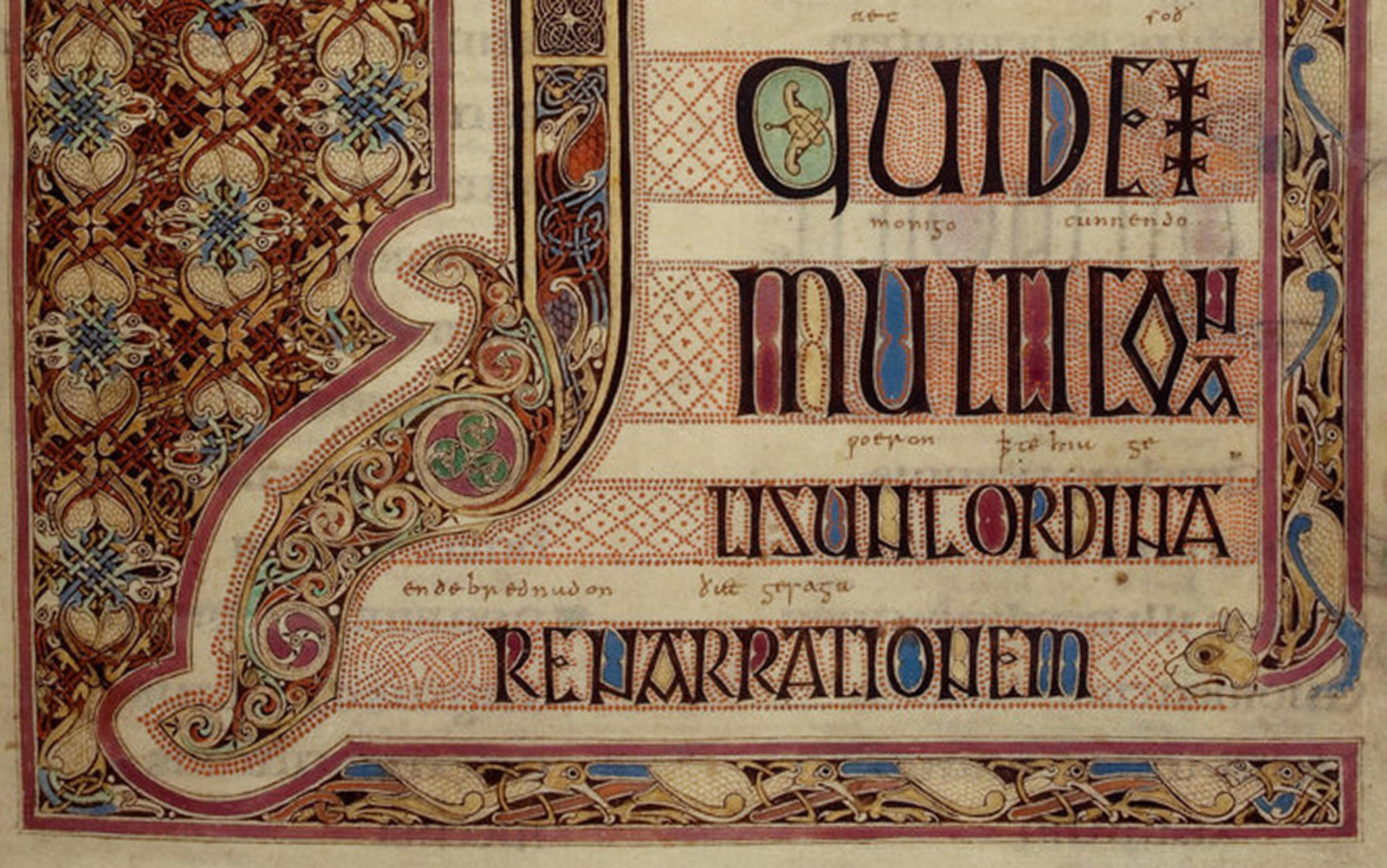

The poem describes a North Sea culture braided from Norse, Christian, Persian and Mediterranean influences. It brings together events from Bunting’s life with the waters that brought the Viking raiders to northern England, and weaves them into the ‘plaited lines’ of the Lindisfarne gospels – the beautiful illustrated manuscripts that were produced by monks on the ‘holy isle’ of Lindisfarne, in honour of St Cuthbert around the 7th century CE. Each page is a dendritic maze coiling endlessly within itself. Up close, the illuminations are tempestuous, as wave upon wave seems to swirl and eddy, then heave into motion again. The chaotic appearance is deceptive, however: stand back, Bunting advises, ‘and it’s as classical, as perfectly placed on the page, as simple in essence, as those Japanese prints with a single spray of cherryblossom’.

Cormorants adorn the opening page for the Gospel of St Luke in the Lindisfarne Gospels. Courtesy the Trustees of the British Library

In the final part of Briggflatts, Bunting arrives at a spot on the Northumbrian coast, where the shore is loud with wildlife. ‘A bangle of birds’ as well as conger eel, lobster, salmon and sea bass crowd a scene in which Bunting imagines ‘St Cuthbert in love with all creation’. Cormorants, or ‘sea-crows’, were closely associated with Cuthbert, because of the cruciform posture they assume to dry their wings. The birds appear 559 times in the Lindisfarne gospels as highly stylised figures. Tails branch out into ribbons; some birds’ necks split to admit threads that plait them into the surrounding lattice. These sinuous lines capture the cormorant in its element as it plunges into the water. This is how the poet Ted Hughes describes the cormorant’s dive:

He sheds everything from his tail end

Except fish-action, becomes fish,

Disappears from bird,

Dissolving himself

Into fish, so dissolving fish naturally

Into himself. Re-emerges, gorged,

Himself as he was, and escapes me.

In the Lindisfarne Gospels, these elegant bird-icons are entangled with brightly coloured ribbons of red and green – ‘all sorts of colours which contradict the natural appearance’, Bunting notes. But as I read Briggflatts, I can’t help but think of more recent images of sea birds ensnarled with unnatural plastic waste, such as Chris Jordan’s series of photographs of dead Laysan albatrosses, each desiccated bird revealing a stomach full of plastic.

As apex predators, albatrosses have significantly higher concentrations of toxic compounds in their bodies than is present in their habitats. Northern fulmars belong to the same seabird family. They are pelagic, which means that they spend their lives foraging out at sea, and return to shore only to breed. They rove from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific and, because of their indiscriminate appetite, they’re effective biomonitors of the distribution and abundance of plastic pollution in the North Sea. Around 95 per cent of northern fulmars in the North Sea now have plastic in their stomachs.

In Flight Ways: Life and Loss at the Edge of Extinction (2014), the environmental philosopher Thom van Dooren explains that animals represent a ‘line of movement’ across evolutionary time. ‘But it is much more than an empty trajectory,’ he writes. ‘Each species lineage embodies a particular way of life, a particular set of morphological and behavioural characteristics that are passed between generations.’ This line of movement isn’t fixed; it’s constantly changing, adapting and transforming. But the problem is that these lines, fashioned over millions of years, are becoming entangled very abruptly in the detritus of fewer than 100 years – the time we’ve been manufacturing plastic and dumping it in the sea. ‘Ask the sea,’ counsels Bunting in Briggflatts, ‘what’s lost, what’s left.’

The Isle of May is a small island in the Firth of Forth, with a humped shape that the historian T C Smout has compared to a sperm whale breaking above the waves. It’s also a key breeding site for Northern fulmars. One of the best places to look out over the Isle is Berwick Law, a hill of igneous rock that stands guard on the mainland at the mouth of the Firth. From the beach near where I live, its pale cone looks almost absurdly regular, a child’s idea of a volcano. In fact, the Law is a volcanic plug, left behind as the surrounding sedimentary rocks were gradually eroded by the thick ice sheets that thawed and reappeared in cycles over millennia, covering and uncovering the whole of Scotland.

I’ve climbed the Law with my children. As well as the Isle of May, you can stare down on Bass Rock, a massive volcanic island glazed white with guano and raucous with gulls, cormorants, guillemots and more than 150,000 northern gannets, the largest colony in the world. Tankers process to and from the refinery at Grangemouth, past the oil platforms and islands bristling with the remnants of wartime forts. From the top, the views are as spectacular as you would imagine, with an unbroken prospect across the North Sea to the west coast of Sweden (if I had a powerful enough telescope, I fancy I could see Orust). But what draws many people to the summit is the whale’s jawbone arch.

A whale jawbone has graced the top of Berwick Law since 1709, when whaling boats sailed out of North Berwick and nearby Dunbar (which happens to be the birthplace of John Muir, founder of the American National Parks movement). Jamie was fascinated by these ‘melancholy beautiful bones’, erected like ‘the arch of a church door’ on islands to the west and north of Scotland and along the eastern coastline of the British Isles. ‘Such has been our violence towards these animals,’ she reflects, ‘that we sense in a jawbone arch a memorial not just to that particular whale, but almost to whalehood itself.’

The replica whale jawbone above North Berwick Law. Courtesy Wikipedia.

In 2008, the whale’s jawbone on Berwick Law was replaced by a fibreglass replica. The duplicate arch puzzled Jamie, just as it puzzled me. ‘In the presence of a whalebone you look at the sea differently,’ she says. A real jawbone ‘pulls the animal’s body, land and sea together in one huge stitch’. The plastic replica, by contrast, is a mark of separation – a monument to the fact that we now tend to learn about the world through the textures of man-made substances. The plastic bones on Berwick Law are only a shadow of the animal, an ersatz rendering of its shape. As Walter Benjamin might put it, the aura of the whale withers in its mechanically reproduced replica. But it’s also a monument to that fact that, after centuries of slaughter, we cared enough to stop.

The plastic will probably endure for many thousands of years. From a human perspective, the new jawbone arch is a permanent presence in the landscape, nearly as resistant to erosion as the rock on which it stands. Like the Bohuslän carvings, its meaning might well be lost to future generations. But, undisturbed, it will represent the thickening of the man-made and the thinning of the non-human by which we have carved ourselves into deep time. The monuments of the Anthropocene, the scraps and scars and traces that will mark our intrusion upon the deep future, are all around us if we choose to look.