Four centuries ago, a woman named Else Knutsdatter was executed in Vardø, a small coastal town in Norway. She was accused of having used witchcraft to raise an ocean storm that claimed the lives of 40 men. She wasn’t the only one to fall victim to 17th-century folk who – in the absence of other explanations – could be convinced that disasters were conjured by malevolent sorcerers. Ninety others were executed for conspiring to produce the same storm.

Today, we know that physics and atmospheric pressures produced those storms. So, in the realm of weather, we’ve moved to systemic thinking, where bad things don’t need to be explained with reference to bad actors. When it comes to descriptions of politics and economics, the progress is not so unequivocal. Do bad things like climate change, conflict and corporate greed happen because powerful politicians and CEOs construct it like that, or do they emerge in the vacuum of human agency, in the fact that nobody’s actually in control? This is a question that confronts me in the campaign to protect the physical cash system against the digital takeover by Big Finance and Big Tech.

Photo supplied by the author

For more than eight years, I’ve advocated for the protection and promotion of physical notes and coins. I wrote a book called Cloudmoney: Why the War on Cash Endangers Our Freedom (2023). In that book, I point out that the public has swallowed a false just-so story that says we are pining for a cashless society. All over the world, public and private sector leaders claim that ‘our’ desire for speed, convenience, scale and interconnection drives an inevitable digital transition. This is supposed to bring a ‘frictionless’ world of digital payment-fuelled commerce, done at the click of a button or scan of the iris. The message is: keep up or else face being left behind.

The fact that so many leaders recite this script triggers some folks into thinking ulterior motives are guiding them, and it is true that the finance and tech sectors, for example, gain massively from the digitisation hype. Over the past few decades, they’ve launched various top-down attacks against the cash system, something I chronicle in my book. Physical cash is issued by governments (via central banks), whereas the units in your bank account are basically ‘digital casino chips’ issued by the likes of Barclays, HSBC and Santander. ‘Cashless society’ is a privatisation, in which power over payments is transferred to the banking sector. Every tap of a contactless card or Apple Pay triggers banks into moving these digital casino chips around for you. It gives them enormous power, revenue and data. They can share that data with governments but, more often than not, they’re using it for their own purposes (such as passing it through AI models to decide whether you get access to things or not).

By rejecting the story that cashless society is driven primarily from the bottom up, I sometimes get accused of being a conspiracy theorist. It’s not hard to imagine the outlines of a ‘conspiracy’ when you look at who benefits most from payments privatisation. Not only are Visa, Mastercard and the banking sector big beneficiaries, the fixation on digitisation also extends the power of Amazon and other corporate behemoths that are moving beyond the internet into the physical world via smart devices and automated stores that plug into digital finance systems. It’s a small jump to imagine how governments can piggyback on this digital enclosure to spy on us, or manipulate us.

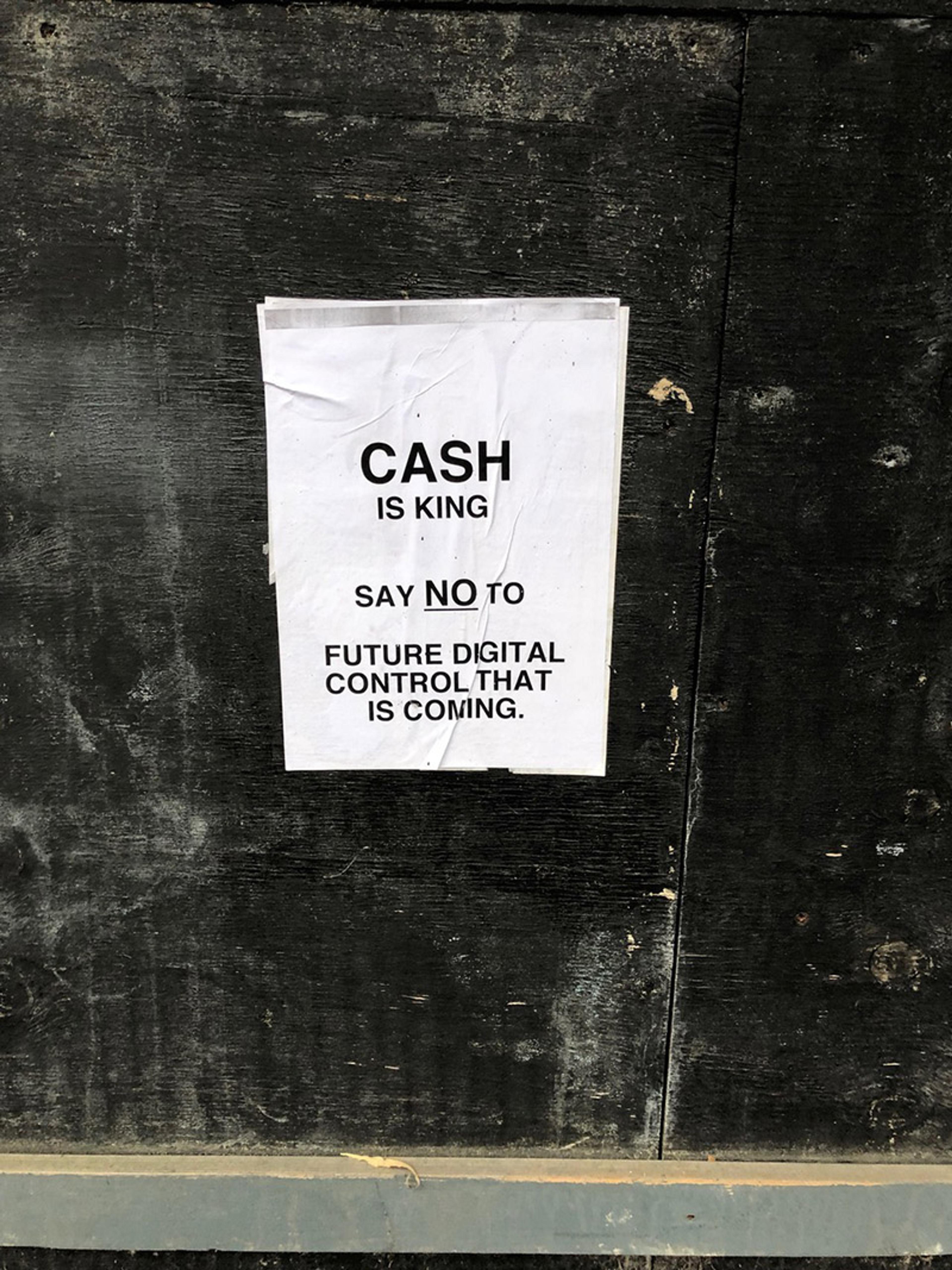

Angst about this creeping enclosure finds widespread expression on social media. In London, and other places where the use of cash has plummeted, it’s turning up in the form of warning posters and pamphlets handed out by conscientious objectors against ‘cashless’ establishments. They warn against a looming digital takeover, but what they don’t realise is that the powerful corporations leading this takeover are themselves led by a larger puppetmaster, and this ‘puppetmaster of puppetmasters’ is no conspiring group of elites. It’s a system, and the dominant stories about digital progress are its ideology.

Systemic thinking requires stretching out the mind to picture powerful but invisible forces. So, let’s ease in through a simple thought experiment: imagine a million blindfolded people tied together, trying to find a direction to walk. They collectively form a system, but its interdependence is so complex that it’s almost impossible for people to coordinate. This means they default to some lowest common denominator, vaguely stumbling in a direction without knowing why. This resembles how our global economic system works. We’re all tied into complex webs of interdependency, and the system generates pressures that require it to expand and accelerate. Its logic demonstrates almost evolutionary properties, such that anyone who goes against its default tendencies hits a wall, while anyone who stumbles in the direction of its prevailing current doesn’t. This may sound abstract, but we can see it clearly at work in the world with physical cash.

For centuries, the capitalist system has been underpinned by nation-states that have fostered the growth of large firms. For a long time, cash helped that system to expand and accelerate. In the 1950s, corporates were more than happy to have adverts featuring people using cash to buy their products, but in the contemporary moment firms are turning against it. Cash is hard to automate. It cannot be plugged into globe-spanning digital infrastructures. It operates at human scale and speed within a system that increasingly demands inhuman scale and speed. It’s creating ‘friction’ at a systemic level, so even if you like cash at a local level, you’ll gradually find yourself coerced away from it.

Amazon lacks infrastructure to process cash, and street-level shops are drawn into this systemic recalibration

‘Coercion’ in this situation doesn’t mean a consortium of CEOs or politicians will force you to stop using cash. If you are tied into a system that contains processes beyond your control, then the system itself can just pull you along. Capitalism often operates on autopilot, with the players following a set formula to boost profits, and one part of that formula is to automate stuff. In 1759, Adam Smith introduced the metaphor of the ‘invisible hand’ to illustrate how all these movements, and these chains of interdependency, can be mapped. For example, Lloyds Bank, guided by shareholder demands for profits, shuts down physical branches to cut costs by pushing you on to automated apps. Having no branches makes it harder for small businesses to deposit cash, so they are nudged toward putting up signs saying ‘We’re cashless.’ That then sends a message to customers that there’s something newly unacceptable about cash. At the same time, people will notice that banks have shut down many ATMs, with the banks justifying this by saying their customers are ‘going digital’, but this creates a self-fulfilling prophesy because removing ATMs lowers public access to cash, making it harder to use. Lloyds and other banks then see the resulting up-tick in digital finance as implicit permission to close down further branches.

What we have here are a series of feedback loops, all serving the prevailing systemic logic of expansion and acceleration. Cashless society, then, is not just a privatisation process, but also an automation process. Automated giants like Amazon in fact lack any infrastructure to process physical cash, and street-level shops are being drawn into this systemic recalibration. Hipster cafés in London have signs saying ‘We’ve gone cashless’; what they are actually saying is ‘We’ve joined an automation alliance with Big Finance, Big Tech, Visa and Mastercard. To interact with us you must interact with them.’

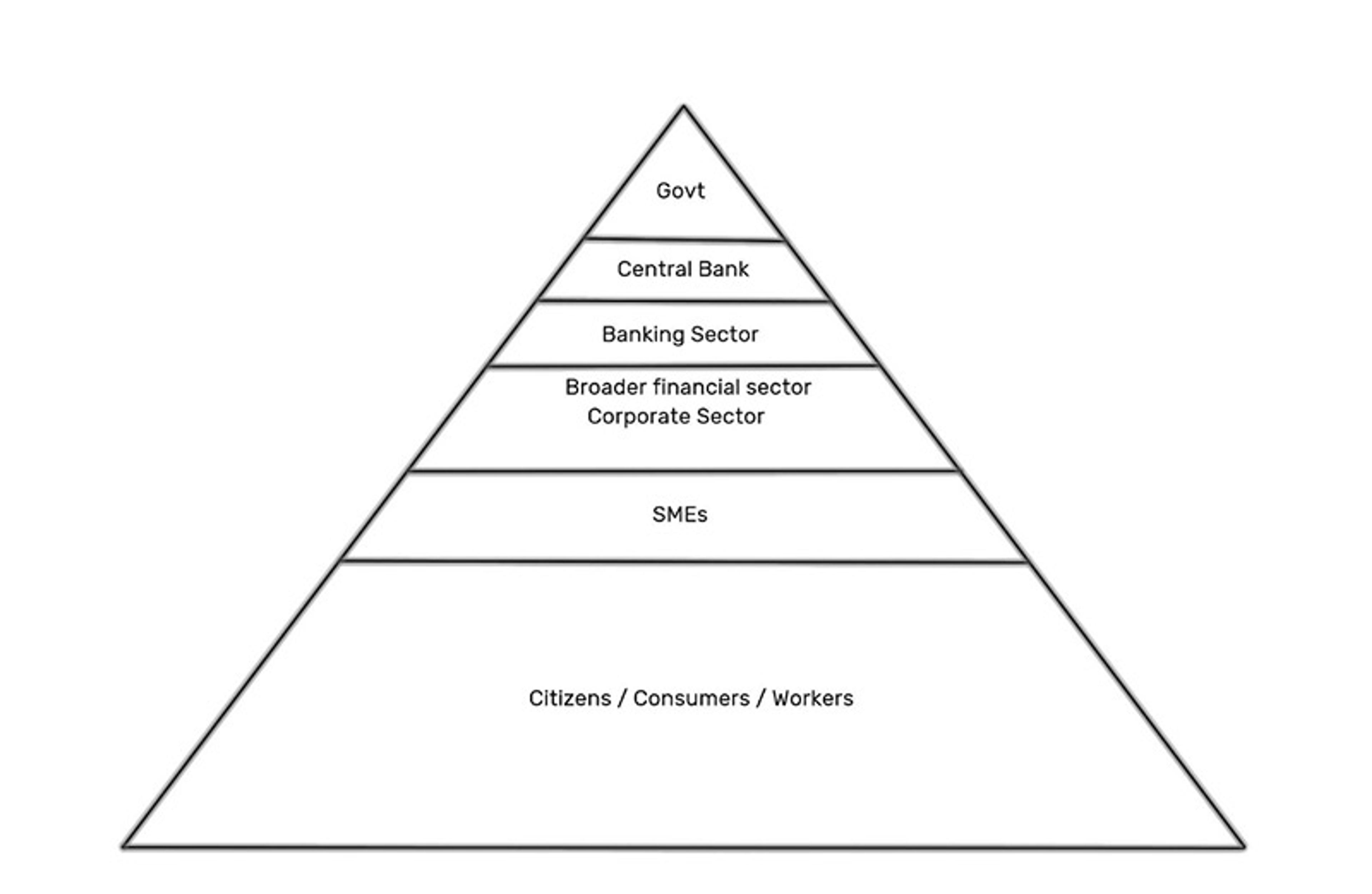

The politics of the ‘invisible hand’ can be visualised with a pyramid:

Where does power lie in this pyramid? Anyone who wishes to divert attention away from the top will likely claim that it resides in numbers, at the bottom. Appealing to legitimacy-from-below is a major tactic used by politicians, who present their governments as reflecting the will of the people, with industry following suit. Rather than admitting to their own interests, banks and fintech companies present the decline of cash as a bottom-up phenomenon driven by popular support. In this view, HSBC’s decision to close ATMs must simply reflect the fact that ordinary people no longer care for cash. In this view, industry simply responds to our demands.

Big firms turn to freemarket doctrine in these situations, which maintains that businesses survive only if they mould themselves to our needs. So the presence of thriving corporations can indicate only that they’re serving us well. Left-wing thinkers reject this freemarket dogma, pointing out that some industries are powerful enough to effectively legislate the conditions of our lives. We all know that firms invest heavily in warping our perceptions via marketing, and often secure our consent only through tricks and misrepresentation. Left-wing calls for government regulation in turn compel freemarketeers to accuse them of stifling both popular will and business. Market conservatives paint a picture of consumers, workers and small entrepreneurs battling the clumsy state, while Lefties present workers, citizens and mom-and-pop shops fighting the corporate behemoths. Economic politics is all about painting these contrasting David-and-Goliath options.

When it comes to money, though, the battle lines get more confusing, because the monetary system is a public-private hybrid. Physical cash is government money, but it has properties – like anonymity – that appeal to some anti-government libertarians. Privacy-invading card-payment systems, by contrast, have historically been run by the private sector, so those pro-business libertarians who are concerned by surveillance are forced to accuse banks of being phoney ‘crony capitalists’ collaborating with controlling governments.

This collaboration can be seen in the case of the 2022 anti-vax ‘Freedom Convoy’ truckers, whose bank accounts were frozen by a Canadian government order. Libertarians rallied in support of the truckers, but there’s many variations of these alliances between states and payments firms. For example, the US government agency USAID has funded programmes like Catalyst: Inclusive Cashless Payment Partnership, pushing Visa as a tool of empowerment in India. In its 2017 annual report, Visa talks about doubling its market penetration into India after it ‘worked closely’ with Narendra Modi’s government in its ‘demonetisation’ efforts in 2016, during which time certain banknotes were outlawed. The Indian prime minister’s open attacks on the public cash system also drew fawning praise from Indian digital-payments firms.

It’s easy to get stuck in a binary of explaining cashless society as either a bottom-up phenomenon demanded by us, or a top-down enclosure pushed by power players. The reality is a more complex mix. Because at scale it’s cheaper to push billions of people through a handful of centralised players, almost every industry in the world is dominated by oligopolies of large firms. Those firms will inevitably build political connections, while smaller firms get relegated to the periphery. Oligopolistic firms fluctuate between collaboration and competition, but the evolutionary logic of our economic system is always towards greater automation. Corporate executives benefit if they nudge everyone in this direction, and they have a niggling insecurity that, if they don’t, competitors will leave them behind. The problem is that many people don’t love digital acceleration, and it takes a considerable effort over time to erode their resistance. This is why big retailers like Tesco start by tentatively testing cashless stores in certain locations to set a precedent. It took years for the airline industry to make it feel ‘normal’ to refuse cash, but that norm is still not universal. Even last year, I found myself seated next to a man on a flight who was humiliated and flustered when the attendants refused his banknote.

The man wasn’t a frequent flyer and came from a working-class background, pointing toward an important fact: when a capitalist system is resetting to a state of higher speed and automation, it often does so first through social elites. In London, a hipster barber targeting yuppies may very well refuse cash, but a hair salon targeting working-class immigrants will almost certainly ‘still’ take it. Words like ‘still’ are loaded, because they imply that whoever is still doing the thing has yet to go through some evolutionary upgrade.

Digital payments giants like Visa invest heavily in presenting ‘going cashless’ as a grassroots triumph for the small entrepreneur who wants to cut costs. In reality, this alliance between Big Finance/Big Tech and small and medium-sized enterprises applies only to businesses with middle-class customers. A decade ago, many of those customers didn’t even perceive cash as particularly inconvenient. Even now, they would prefer choice (the fact that I sometimes use my card doesn’t mean I asked a shop to remove its cash till). It’s businesses that remove our payments choice, but they rely on the fact that most middle-class people simply adapt their expectations and edit their memories to forget those old days when cash felt totally normal. Once new cultural norms are established, it compels compliance. Eventually, you get discriminated against if you insist on being that guy who complains that the London bar won’t accept your coins.

The fact that people fall into line and begin displaying a preference for card payments is read by politicians as a signal to support the transition. They too are worried about being ‘left behind’. This pressure to go along with the transnational automation drive means that the average UK Labour Party politician doesn’t challenge cashless society. Rather, they call for a slight slowdown in the imagined ‘race’ towards it, to give cash-dependent communities a chance to ‘catch up’.

Cashless pubs allow hundreds of unmasked people in while refusing cash to protect their employees

So, capitalism has inherent trends, but it also has inherent contradictions. Here’s one of them. Our cashless card payments rely upon ‘digital casino chips’ issued to us by banks, but – as anyone who has been to a casino knows – such chips have power only because you believe they can be redeemed for cash. In the total absence of cash, there could be a collapse in the public’s belief in bank-issued digital money. Banks and corporates make private decisions that erode our cash infrastructure, but in doing so they are undermining the public basis of confidence in their private systems.

This was accelerated by the outbreak of COVID-19, which gave companies a convenient cover to fast-track their automation plans. It’s easier for a retailer to announce they don’t accept cash because of COVID-19 than to admit that they’re trying to shave a percent off their costs. For example, Visa entered a deal with the US National Football League to promote cashless Super Bowls. Signed in 2019 and piloted in 2020, it went public in 2021 during the pandemic, with attendant media coverage presenting it as a measure of public hygiene. Cashless pubs in London allow hundreds of unmasked people in their establishments while claiming to refuse cash to protect their employees from any coronavirus that may be stuck to the notes (a contention that is scientifically inaccurate).

In 2020, such scaremongering, along with the fact that so many of us were forced into online shopping during the pandemic, caused a precipitous drop in transactional cash use. This raised the possibility of a financial stability problem, because cash psychologically (and legally) backs our cashless digital casino chips. This puts central banks in a bind. They know that the trajectory leads to a crisis-prone bank-dominated version of cashless society. So they think about how to maintain public access to government money without upsetting the transnational automation agenda. One way they are trying to resolve this is with a new form of ‘digital cash’ – central bank digital currency (CBDC).

To understand CBDC, imagine being able to download a payments app on the iPhone App Store from your nation’s central bank (like the US Federal Reserve or the Bank of England). Various countries have appointed teams to experiment with this hypothetical government payment system, but it creates a new problem. In a country like the UK, a state-issued digital pound would upset banking giants like Barclays, Lloyds and HSBC. They would rightly perceive it as competition to their own digital money empires. Given that central banks are supposed to maintain the stability of private banks, rather than directly compete with them, the Bank of England (and all other central banks) will have to make concessions: any future CBDC will be watered down to prevent disruption to the banking sector, and its operation will be outsourced to private partners… like the banks themselves.

In 2015, I was one of the few people raising awareness of the dangers of cashless society from a Left-wing perspective. Then the pandemic hit, and a new generation of pro-cash activism emerged in the so-called populist Right. Libertarians seized upon early COVID-19 controls as evidence of a new era in totalitarianism. Social conservatives had already cast Big Tech firms as hives of ‘wokeness’. Conservative commentators began to weave these perspectives together. They presented themselves as rebellious champions protecting the everyman from an alliance of liberal corporate elites and authoritarian socialist governments.

In May 2020, my mother was sent a video by her friend on Facebook. It claimed that Bill Gates had orchestrated COVID-19 to microchip us via vaccines and to usher in a cashless society where our every economic move could be monitored. Her friend was very excited to announce that ‘Your son is in this! You must be so proud.’ Sure enough, there was a clip of me (used without my permission), in which I was describing how financial institutions engage in a war on cash. It was followed by a clip of an evangelical pastor warning that ‘the Bible clearly links the mark of the beast with the emergence of a cashless society’.

How is it that I end up in a video like this? Conspiracy theorists happily take my work out of context in order to push their version of events. Rather than analysing the logic of capitalism, many of them have decided that behind digital innovation-speak lie satanic overlords, paedophiles, Marxists, Jews or caricatured banksters smoking cigars.

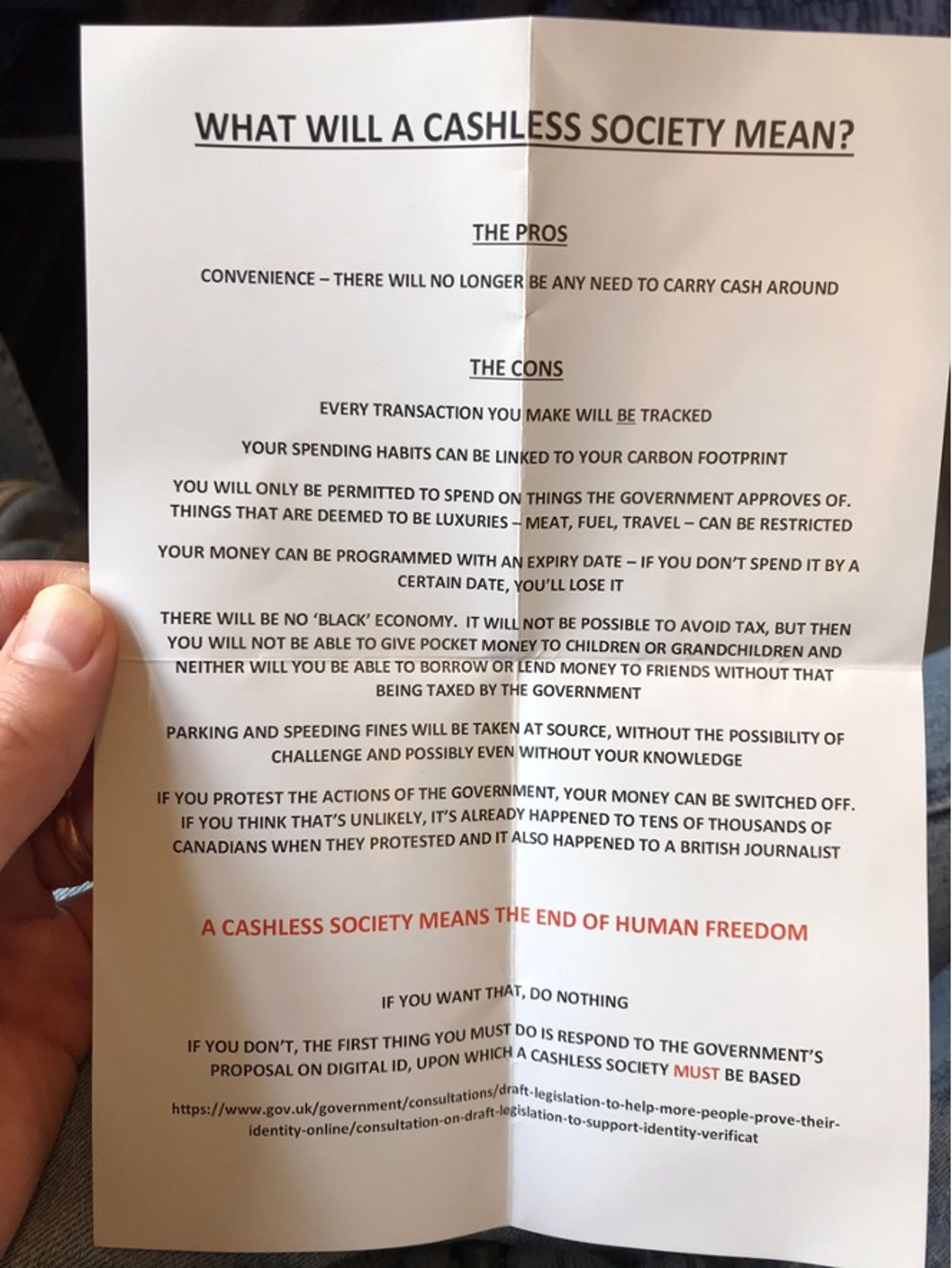

Ironically, it’s central banks’ response to the corporate attack on cash that has really spurred the new wave of pro-cash activism. The possibility of a state-controlled digital pound or digital euro replacing the battered cash system has galvanised the imagination of libertarian activists. Libertarians have always faced a tension when complaining about the surveillance that accompanies cashless society. This is because digital payment systems are pushed by private sector fintech entrepreneurs, and libertarians are supposed to be pro-entrepreneurialism. CBDC has enabled them to escape this bind. It allows them to rework the story of cashless society as being driven by an oppressive digital state.

These systems limit choice, and can be used to push people’s business to big retailers, rather than small ones

This mutated version of the cashless society story is now spreading virally. My dad recently forwarded me a video, which he received on WhatsApp, about the looming spectre of CBDC. The anonymous producers stitched together clips from libertarian activists, self-help gurus and even the populist UK politician Nigel Farage, all of whom cast CBDC as a new form of digital totalitarianism. They argued that this centralised digital money will be sold to us under the banner of convenience, but that the true agenda is to enable governments to micromanage us by controlling our payments. The conclusion? Say no to CBDC. Say yes to physical cash.

They’re not wrong to point out the dangers of digital control, but their selective curation of the form and examples misrepresents why it is happening and how to oppose it. The cashless system is run by transnational corporations, and the actually existing examples of payments control often concern welfare recipients: for instance, the Australian ‘cashless welfare card’ was a Visa card system that blocked Indigenous Australians on benefits from buying non-approved goods in non-approved stores. These systems not only limit choice, but can be used to push people’s business to big retailers, rather than small ones.

Farage and his contemporaries don’t focus on the payments censorship of Indigenous welfare recipients. They fixate on conservative fears, like the hypothetical blocking of transactions for guns and meat. This is causing me problems, because moderate progressives – who previously would have expressed some concern about corporate power – have started associating a pro-cash stance with reactionaries, and to a broader suite of ideas that they espouse. In Germany, I’ve even been accused of being aligned with the neo-Nazi Reichsbürger movement, purely on the basis that they too are pro-cash. I’ve seen digital payments promoters use this disorientation to their advantage. They can suggest that critiques of their industry are the realm of crackpot antisemites. If conspiracy theorists are the ones leading the charge against digitisation, surely it must show the concern is built from the wild fantasies of paranoid flat-Earthers. Rather than fight cashless society, then, they suggest we should promote corporate financial inclusion: give a helping hand to all those people who have yet to be absorbed into Big Finance. Get them accounts. Help them become corporate consumers.

Moderate progressives are often taken in by this story and in backing away from the cashless society battle they cede territory to the far Right. It’s an example of a trend in our post-pandemic moment, where the meeting of two sides of the political horseshoe has led to the spread of Right-wing ideas among people who previously considered themselves Leftists. The new Right has appropriated the rebellious language of Left-wing hacker culture, which pushed digital privacy for decades (for a pop-culture version of this, watch the TV series Mr. Robot, in which anti-capitalist hackers target the corporate giant ‘Evil Corp’). Top-down power has been re-ascribed to a generic blob of ‘globalists’, acting via institutions like the World Economic Forum (WEF), but anti-WEF campaigning was a standard part of Left-wing culture in the 1990s and ’00s. To Left-wingers, the WEF represented venal corporate capitalists, which is why the ‘alter-globalisation’ movement championed the World Social Forum as an alternative. In the midst of lockdowns, however, it was anti-mask and anti-vax campaigners who took on the aesthetics of Occupy Wall Street, holding street protests with placards warning about cashless society and digital ID.

A surreal twilight zone has formed between the language of the old Left and that of the populist Right, and into it has stepped a character like Russell Brand. In 2013, he came out as an anti-corporate socialist and, back then, every Lefty activist I knew was clamouring to find his email address in the hope that he’d platform their cause. Fast-forward several years, and he renamed his podcast to Stay Free, peppering it with libertarian language and topics that appeal to the Right. He presents himself as being on an open-minded search for the truth that the mainstream media won’t tell us, and it increasingly involves him having discussions with conservative edge-lords. In November 2022, he released an obligatory video about CBDCs, entitled ‘Oh Sh*t, It’s REALLY Happening’.

Notably, no cashless establishments use CBDC, because it doesn’t exist yet. They all use the private sector digital payments system but, in choosing to focus on the fantasy version of cashless society, rather than the actual one, Brand signals that his allegiance lies with the Right wing.

In the martial arts classic Kill Bill: Vol 2 (2004), the five-point palm exploding-heart technique is a precise sequence of five hits that cause an opponent’s heart to stop. In the conspiracy world, the five-point punch of the globalists involves them hitting us with digital IDs, 5G technology, vaccines, COVID-19 passports and now CBDCs. This is supposed to trigger a global cardiac arrest called the ‘Great Reset’. The Great Reset is actually the name of a real programme convened by the WEF, in which they talk about the need for a post-pandemic digital and green transition. Those goals emerge from different sources because, while capitalism generates a digitisation agenda to speed things up, it doesn’t generate a conservation impulse to slow things down. Green transition rhetoric doesn’t emerge from market processes: it’s the result of decades of relentless campaigning from civil society groups, who pushed past the lobbying of the fossil fuel industry to showcase the economic risks of climate change. Big business and politicians now pay lip service to that.

Nevertheless, they attempt to subordinate it to their automation fixation by proposing digital techno-fixes for climate change. This is a gift to our conspiracy theorists. They can now present CBDCs as being a future tool to force us to buy only low-carbon vegan sausages, under the control of Greta Thunberg and the Bank for International Settlements (a BIS video about CBDC is a favourite among them).

An anti-cashless society propaganda leaflet. Supplied by the author

Cashless society authentically sucks. It’s a world where your kid cannot sell lemonade on the side of the road without paying Mastercard executives in New York. It’s an attack on privacy, autonomy, local independence and casual informal interactions in favour of surveillance, dependence and centralisation of power in large institutions. I frequently interact with people who have very real concerns about it, but who – like our 17th-century folk who lost loved ones to a storm – have been steered into reactionary ideas about it. Our struggle to see large-scale systemic processes gives oxygen to conspiracy theorists. I frequently get asked to go on Right-wing media channels, such as GB News, to be interviewed by anti-woke libertarians or Christian evangelists. Many of them imagine capitalism to be the realm of the small individual, and present elites as being malevolent actors who attack the system from above. It’s an easy story to tell. But the reality is that elites are a by-product of our system. The invisible hand likes tapping the contactless card, regardless of whether you as an individual do, and the role of the elites in the war on cash is to simply unblock resistance to that. More often than not, they’re examples of Hannah Arendt’s banality of evil. They’re just people ‘doing their job’, serving a system that wants to commodify any aspect of our lives that remains un-commodified and un-automated.

The dominant tendencies in capitalism pull upon all of us but it’s possible to demand space for other values. It’s been done before. There was a time when the automobile industry seemed ascendant, and bikes were pushed off the roads, but we built a cultural movement to demand bicycle lanes. That’s why we should see cash as being like the public bicycle of payments, and support efforts across the political spectrum to protect and promote it. Digital bank systems are the private Uber of payments: they may appear convenient, but total Uberisation unleashes demons that cash historically kept in check – surveillance, censorship, digital exclusion, and serious resilience and financial stability problems. The point isn’t to argue that everyone must always use the ‘bicycle’. It’s to ensure that we don’t get totally ‘Uberised’ in private and public life. We need to promote a healthy balance of power between different forms of money in the system, and that’s within our collective political abilities.